CHAPTER 41 Congenital Heart Disease

Cardiac congenital abnormalities account for less than 3 per cent of all cardiac abnormalities seen in cats. Definitive diagnosis of most congenital abnormalities can be accomplished with a combination of historical findings, physical examination findings, thoracic radiographs, echocardiography, and electrocardiography (ECG). The more common feline cardiac congenital abnormalities, including mitral and tricuspid valve dysplasia, patent ductus arteriosus, aortic stenosis, pulmonic stenosis, ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot, endocardial fibroelastosis, and peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia, have been summarized previously.1 This chapter will provide updated information on the more common feline cardiac congenital abnormalities and an expanded discussion of the less common congenital abnormalities.

MITRAL VALVE DYSPLASIA

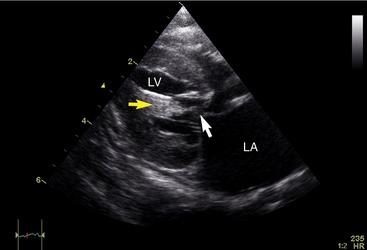

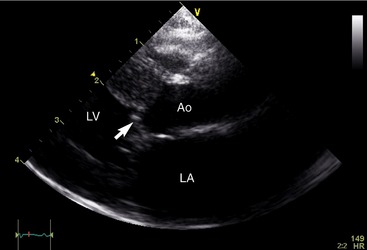

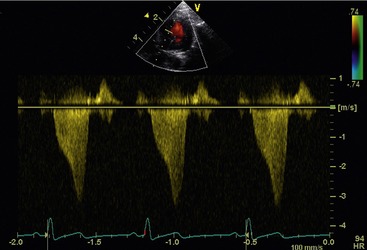

Mitral valve dysplasia (MVD), in the most general sense, is a developmental anatomical abnormality of the mitral valve apparatus. This may include malformations of the valve leaflets, valve annulus, chordae tendineae, papillary muscles, or a combination thereof (Figure 41-1). The abnormality results most commonly in mitral regurgitation, but stenosis of the mitral valve has been reported.2 Additionally, dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and mitral regurgitation may occur as a result of systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve associated with mitral valve malformation. If the outflow tract obstruction is severe, left ventricular concentric hypertrophy may occur. This may be difficult to distinguish from primary hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with secondary systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve (hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy). Cats with significant outflow tract obstructions and mitral regurgitation secondary to SAM of the mitral valve can present with clinical signs of syncope, exercise intolerance, and left-sided congestive heart failure (lethargy, respiratory difficulty) as kittens or young adult patients. Physical examination reveals a left apical sternal systolic murmur of mitral regurgitation, a left basilar systolic ejection murmur, or both. Two-dimensional echocardiography reveals SAM of the mitral valve (Figure 41-2) in addition to the other anatomical abnormalities consistent with MVD. If SAM of the mitral valve is present, the transaortic velocities are increased commensurate with the degree of obstruction and the spectral Doppler envelope may assume a dagger shape commensurate with the degree of obstruction (Figure 41-3). Beta-blocker therapy may help to alleviate the left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and may promote resolution of attendant hypertrophy.

Cats with mitral stenosis may present with lethargy, exercise intolerance, and signs of left-sided congestive heart failure. Physical examination findings may reveal a left apical diastolic murmur, although this is exceptionally difficult to appreciate in most cats because of the high heart rate. In cases of isolated mitral stenosis, there will be discordance between the severity of the enlargement of the left atrium and the left ventricle, the degree of left atrial enlargement being significantly greater than that of the left ventricle because of diastolic obstruction of blood flow from the left atrium to the left ventricle. Two-dimensional echocardiography reveals valve leaflets with a decreased diastolic excursion. Color and spectral Doppler echocardiography reveal high velocity, disturbed transmitral flow with a prolonged pressure half-time.3 Definitive treatment of a stenotic valve involves cardiopulmonary bypass and has not been reported in the veterinary literature. Balloon dilation of a stenotic mitral valve is another interventional option. Severe mitral regurgitation may develop following dilation, making this a less desirable treatment choice. Therefore medical management of left-sided congestive heart failure secondary to mitral stenosis is utilized and includes the use of diuretics and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Potent vasodilators must be used with caution, if at all, because the obstructed left ventricular inflow may predispose to severe systemic hypotension. Isolated mitral valve stenosis puts patients at high risk for thromboembolism; therefore therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin is warranted.

TRICUSPID VALVE DYSPLASIA

Tricuspid valve dysplasia (TVD) is characterized by an anatomical abnormality of the tricuspid valve apparatus, which may include the valve leaflets, valve annulus, chordae tendineae, papillary muscles, or a combination of these structures. Most commonly lesions associated with TVD lead to a regurgitant jet and signs of right ventricular and right atrial eccentric hypertrophy, although tricuspid stenosis has been reported.4 The stenosis may be present in addition to tricuspid regurgitation. Many cats who present with tricuspid valve stenosis are asymptomatic, and cats with mild lesions may remain asymptomatic through adulthood or develop signs of congestive heart failure during adulthood. Signs of heart failure, including lethargy, dyspnea, weight loss, anorexia, and abdominal distension, may be present in young cats with significant lesions.5 Physical examination findings in cats with tricuspid stenosis reveal a right-sided parasternal diastolic murmur (in addition to a systolic murmur if regurgitation of the valve is present). With tricuspid stenosis there is significantly greater enlargement of the right atrium than the right ventricle because of impaired diastolic filling of the right ventricle. The valve leaflets have a decreased excursion in diastole, and color and spectral Doppler echocardiography reveal turbulent blood flow in the right ventricle just distal to the tricuspid valve. As with MVD, definitive treatment of the abnormal valve apparatus involves cardiopulmonary bypass and valve replacement. Because of their small size and cost of the procedure, this often is not a viable option for cats. Balloon dilation of a stenotic tricuspid valve is a possibility, because the residual tricuspid regurgitation is not as hemodynamically significant as that associated with the original stenosis. However, this procedure has not been reported to date, to the best of the author’s knowledge. Therefore medical management of right-sided congestive heart failure is instituted and includes the use of diuretics and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, with or without vasodilator therapy.

PATENT DUCTUS ARTERIOSUS

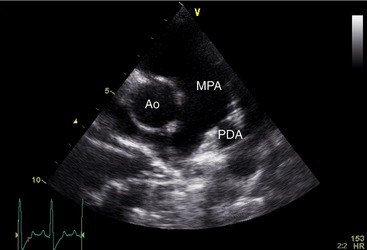

Failure of a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) to close after birth results in a shunting of blood from the descending aorta to the pulmonary artery, resulting in a volume load placed on the pulmonary vasculature and left heart. Although the murmur of PDA in dogs is classically continuous, the high heart rate in cats sometimes makes appreciation of the diastolic component challenging in this species. Thoracic radiography documents variable degrees of left heart enlargement and pulmonary overcirculation commensurate with volumetric shunting (Figure 41-4). Echocardiography is used to confirm the diagnosis by documenting the presence of continuous disturbed flow within the main pulmonary artery (Figure 41-5). Surgical ligation is the more common definitive treatment; however, transvenous coil embolization has been reported in cats, representing an additional method of definitive treatment.6

PULMONIC STENOSIS

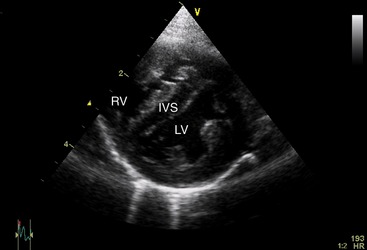

Lesions of pulmonic stenosis can be primarily valvular, supravalvular, or subvalvular in location, resulting in right ventricular concentric hypertrophy secondary to the pressure load induced by the stenosis. In addition to fixed anatomical obstruction, a dynamic component often is present. Definitive diagnosis is confirmed with echocardiography. Common features of moderate to severe pulmonic stenosis include accelerated transpulmonary flow velocity, global right ventricular hypertrophy, and flattening of the interventricular septum (Figure 41-6). Beta blockade may help to alleviate any dynamic component, but relief of the anatomical obstruction requires either surgical repair or an interventional catheterization procedure. Balloon valvuloplasty has been reported in cats with favorable outcomes.7 In addition, balloon valvuloplasty has been performed successfully in cats who have infundibular stenosis (the muscular portion of the right ventricular outflow tract extending between the right ventricle and the pulmonary valve).8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree