CHAPTER 14 Congenital and Hereditary Skin Diseases

Congenital and hereditary defects of the skin are rarely reported and usually untreatable.1–7 Many of the disorders have an unproven mode of inheritance or are transmitted as recessive traits. Breeding of apparently normal parents or siblings of an affected horse distributes the gene more widely. Breeders of horses with suspected or proven genodermatoses should be instructed to avoid breeding of all close relatives of the affected animal, unless genetic testing, if available, can be done to rule out carrier status.

Disorders of the skin and follicular epithelium

Aplasia Cutis Congenita

Aplasia cutis congenita (epitheliogenesis imperfecta) is a very rare congenital and perhaps inherited failure to form certain layers of skin.1a,5 The condition is a developmental failure of skin fusion. Dermis, epidermis, and fat may all be missing, or single layers may be absent.

Aplasia cutis congenita has been reported several times in the horse.5 However, careful evaluation of the clinical findings and the histopathology (when reported and illustrated) suggests that the majority of these foals had epidermolysis bullosa. A few animals had solitary or regionalized lesions of the distal leg or face consistent with aplasia cutis congenita. The lesions were characterized by round, to oval, to linear areas of well-circumscribed ulcerations (Fig. 14-1). Secondary infection is a possible complication. The major differential diagnosis is obstetric trauma. Small lesions may, with supportive therapy, heal by scar formation. Alternatively, lesions may be treated by surgical excision or skin grafting techniques.

Epidermolysis Bullosa

The term epidermolysis bullosa refers to a group of hereditary mechanobullous diseases whose common primary feature is the formation of blisters following trivial trauma.1a,5,7 In humans, classification is by mode of inheritance, histopathologic and ultrastructural features, and, if known, the specific genetic defect (Table 14-1).

TABLE 14-1 Types of Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB) in Humans1a

| Type of EB | Structure Affected | Deficient Protein |

|---|---|---|

| EB simplex (EBS) | ||

| Generalized EBS (Koebner) | Intermediate filaments | Keratins 5, 14 |

| Localized EBS (Weber-Cockayne) | Intermediate filaments | Keratins 5, 14 |

| EB herpetiformis (Dowling-Meara) | Intermediate filaments | Keratins 5, 14 |

| Junctional EB (JEB) | ||

| JEB gravis (Herlitz) | Anchoring filaments | Laminin 5α3, β3, γ2 |

| JEB mitis | Anchoring filaments | Laminin 5α3, β3, γ2 |

| JEB-pyloric atresia | Hemidesmosomes | Integrins α6 or β4 |

| Dystrophic EB (DEB) | ||

| Dominant DEB | Anchoring fibrils | Type VII collagen |

| Recessive DEB | Anchoring fibrils | Type VII collagen |

Cause and pathogenesis

Although wide variation exists in clinical severity and inheritance, epidermolysis bullosa in humans is currently divided into three groups based on histopathologic and ultrastructural findings: epidermolysis bullosa simplex (blister cleavage occurs within the stratum basale of the epidermis); junctional epidermolysis bullosa (blister cleavage occurs within the lamina lucida of the basement membrane zone); and dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (blister cleavage occurs within the sublamina densa area of the basement membrane zone). The most frequently and well-documented cases of equine epidermolysis bullosa fall into the junctional group. The pathogenesis of the various forms of epidermolysis bullosa is not completely described but focuses on abnormal keratin intermediate filament and keratin network formation and abnormal anchoring mechanisms (types VII and XVII collagen, laminin, plectin, integrins) (see Table 14-1).1a,5

Although epidermolysis bullosa was first described in horses in 1988, it is very likely that most reported cases of so-called “epitheliogenesis imperfecta” were, in fact, foals with epidermolysis bullosa.5 Most cases of well-documented equine epidermolysis bullosa have involved draft horses, especially Belgians and two French breeds, the Trait Breton, and Trait Comtois.* In these three breeds (that share common ancestors), the condition is autosomal recessive, the same disease phenotype is expressed, and the genetic defect is the same: a mutation in the γ2 subunit of laminin 5 (LAMC2 gene) on equine chromosome 5.12,13 A similar disease has been reported to occur in warmbloods and appaloosas.4

In American saddlebreds, the condition is also autosomal recessive, but the defective gene (LAMA3) maps to equine chromosome 8 and results in a mutation of the α3-subunit of laminin 5.9-11,14 It has been suggested that the condition in American saddlebreds should be called “epitheliogenesis imperfecta” to not confuse it with the condition in draft horses.3,4 This is illogical and erroneous. There are many forms of epidermolysis bullosa in humans, a fact that is not referred to as confusing.1a “Epitheliogenesis” indicates that the abnormality is epithelial in nature, but it is not.

In one quarter horse foal, the defect was reported to be a lack of the intracellular plaque protein plectin, making this a simplex form of epidermolysis bullosa.8 The foal’s parents were normal and unrelated.

Clinical features

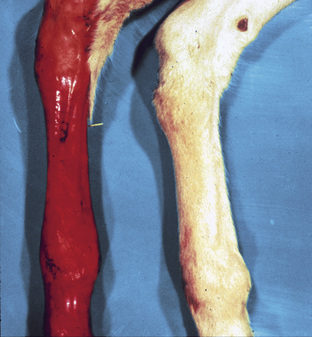

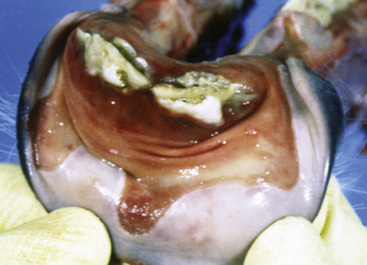

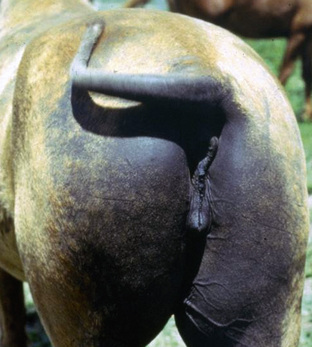

The most commonly reported epidermolysis bullosa is the junctional form seen in Belgians, Trait Breton, Trait Comtois, and American saddlebreds.5-7,9-14, There is no sex predilection. Foals may be born with lesions or develop lesions within the first 2 days of life. Primary skin lesions are vesicles and bullae, but these are transient, easily ruptured, and usually absent when the foals are initially examined. The predominant clinical lesions are well-demarcated ulcers, often with peripheral epidermal and mucosal collarettes. Exudation and crusting is often pronounced. Lesions are typically present on the coronets (Fig. 14-2); the mucocutaneous junctions of the lips, anus, vulva, eyelids, and nostrils; over areas of bony prominences (Figs. 14-3 and 14-4), such as the fetlocks, hocks, carpi, stifles, hips, and rump; and in the oral cavity (Figs. 14-5 and 14-6). Hoof wall separation usually progresses to complete exungulation (sloughing of hoof capsules). Lesions may also be observed on the cornea and in the esophagus. Enamel hypoplasia is typically present and is characterized by irregular, serrated edges and enamel pits on incisors and cheek teeth. Affected foals become progressively depressed and cachectic, and are euthanized or die of septicemia.

Figure 14-2 Junctional epidermolysis bullosa. Ulceration of the coronary band and sloughing of the hoof.

The foal with the simplex form of epidermolysis bullosa had alopecic, scarlike striations in the skin over the withers, chest, and upper limbs, and laminitis of all four feet.8 The coronary bands, mucocutaneous junctions, and oral mucosa were unaffected. The foal was euthanized.

Diagnosis

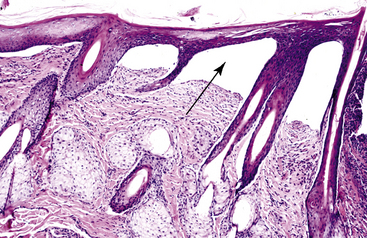

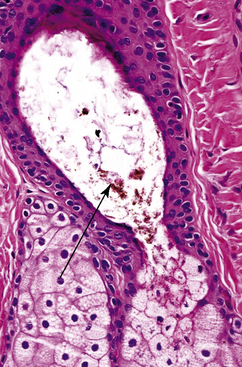

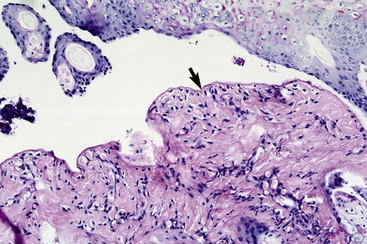

In the junctional form of epidermolysis bullosa, skin biopsy reveals subepidermal cleft and vesicle/bulla formation (Fig. 14-7).5,9–13 Inflammation is minimal except where ulceration, infection, or both of these have occurred. Biopsy specimens stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) usually show the PAS-positive basement membrane zone attached to the dermal floor of the clefts and vesicles (Fig. 14-8). Ultrastructural studies reveal that dermoepidermal separation occurs in the lamina lucida of the basement membrane zone and that hemidesmosomes are small, abnormal, and reduced in number.5,13 Immunohistochemical studies reveal a lack of laminin 5.

Figure 14-8 Junctional epidermolysis bullosa. Same biopsy specimen as in Fig. 14-7. Special stain reveals that basement membrane zone is at floor of vesicle (arrow) (PAS stain).

In the simplex form of epidermolysis bullosa, skin biopsy and ultrastructural studies reveal subepidermal cleft and vesicle/bulla formation due to epidermal basal cell degeneration, cytoskeletal collapse, and hemidesmosome disarray.8 Immunohistochemical studies reveal a lack of plectin.

Clinical management

There is presently no effective treatment for equine epidermolysis bullosa. The clinician should inform the owner of the nature and heritability of the disorder, and the stallion and mare should not be used for further breeding. Genetic testing is available (Veterinary Genetics Laboratory at the University of California: www.vgl.ucdavis.edu/services/horse) to determine carrier or affected status in Belgians, Trait Breton, and Trait Comtois.1,4,7 In North America, this testing indicated that 32% of the Belgian draft horse population were heterozygous carriers of the mutation in γ2 laminin 5. Another study found that 5% of American saddlebreds were heterozygous carriers of the α3 laminin 5 mutation.11

Erythrokeratodermia Variabilis

The palmoplantar keratodermas are a heterogenous group of disorders characterized by abnormal thickening of the palms and soles in humans.1a The disorders may be hereditary or acquired.

A disorder resembling erythrokeratodermia variabilis (autosomal dominant in humans) was reported in a newborn female warmblood.15 The horse was born with “crumbly” hooves and symmetric lesions over bony prominences of the limbs. The lesions were hyperkeratotic plaques. Histologic examination revealed marked hyperkeratosis and epidermal hyperplasia. The animal was euthanized at 9-weeks-old and no necropsy was performed.

Hypotrichosis

Hypotrichosis implies a less-than-normal amount of hair and a congenital, possibly hereditary, basis for the condition.5,16 Hypotrichosis may be regional or multifocal in distribution, but is usually generalized. Reports of hypotrichosis in the horse are extremely rare, anecdotal, and sketchy. Anecdotal reports indicate that a hereditary hypotrichosis occurs in certain lines of Arabians.5 Hair loss is symmetric and restricted to the face, especially the periocular area (Fig. 14-9). Skin in affected areas may be scaly and feel thinner than normal.

Figure 14-9 Hypotrichosis. Poor hair quality and hair loss on the face of an Arabian.

(Courtesy R. Pascoe.)

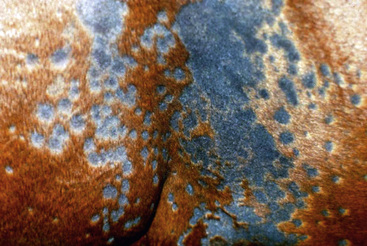

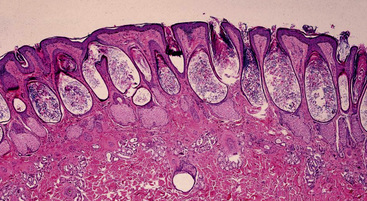

Congenital hypotrichosis was reported in a blue roan Percheron.16 The horse was born with poorly circumscribed patchy alopecia of the trunk and legs. Teeth and hooves were normal. Alopecia was progressive, becoming almost complete by 1-year-old (Fig. 14-10). Histopathologic findings included follicular hypoplasia and hyperkeratosis and a predominance of catagen and telogen hair follicles (Figs. 14-11 and 14-12). Melanotic debris was present in the lumina of many hair follicles and sebaceous glands. The horse was in good health at 5-years-old, but was susceptible to sunburn.

Figure 14-11 Congenital hypotrichosis. Hair follicles are hypoplastic, keratin-filled, and devoid of hairs.

Trichorrhexis Nodosa

Trichorrhexis nodosa is a hair shaft defect that may be hereditary or acquired (see Chapter 10).1a,5

Follicular Dysplasia Syndromes

Follicular dysplasias (e.g., “mane and tail dystrophy,” “black and white hair follicle dystrophies,” “color-dilution alopecia”) have rarely been reported in horses and are probably genetic in origin.2,5,6 Mane and tail follicular dysplasia is recognized at birth or at a few weeks of age. It is particularly common in appaloosas and horses with the curly coat phenotype.5,18 Affected animals have short, brittle, dull hairs and variable alopecia in the mane and tail (Figs. 14-13–14-15). Black or white hair follicular dysplasias are also recognized at birth or in juvenile animals.2,5,6 Patches of hair coat in either black- or white-haired areas are short, brittle, and dull. Affected areas usually become hypotrichotic-to-alopecic. Follicular dysplasia resembling color-dilution alopecia in dogs was reported in a young Percheron-Thoroughbred cross-gelding with a blue-gray hair coat.17 The horse developed annular, 1- to 2-cm diameter areas of alopecia on the face, neck, shoulders, chest, and back, and almost complete loss of mane and tail hairs. The authors have received biopsies with limited clinical and follow-up information on a few horses with more widespread (trunk and neck), noncolor-related follicular dysplasias. These animals had brittle, dull, hypotrichotic hair coats with irregular hair lengths (breakage), annular areas of alopecia (Figs. 14-16 and 14-17), and a tendency toward dry, scaly skin in affected areas.

Figure 14-15 Follicular dysplasia. Note alopecia over rump, tail, and caudal thighs of a curly coat horse.