Chapter 4 Conformation and Lameness

The thought that the way a horse is conformed determines the way it moves is well accepted. The relationship of conformation, especially of the distal extremities, and lameness also is well recognized. “Conformation determines the shape, wear, flight of the foot, and distribution of weight.”2 Veterinarians often are asked to comment on conformation during lameness and prepurchase examinations, especially with regard to the suitability of the horse to perform the intended task. In some instances, as in the case of presale yearling evaluations, the veterinarian’s opinion is paramount, and purchase is contingent on judgment of the yearling’s potential to perform as a racehorse, given its conformation, or in some instances its conformational faults (see Chapter 99). “It is by a study of conformation that we assign to a horse the particular place and purpose to which he is best adapted as a living machine and estimate his capacity for work, and the highest success in this connection will be best attained by the judicious blending of practice with science.”3 Evaluation of conformation and its influence on lameness is based largely on observation, experience, and pattern recognition. Recognizing desirable conformational traits in horses suited for a particular sporting activity and learning when to overlook a minor fault that has little clinical relevance are important.

Objective Evaluation of Conformation: Is It Possible?

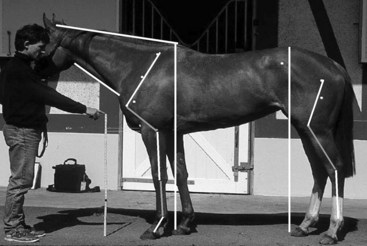

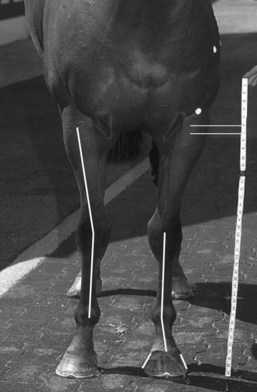

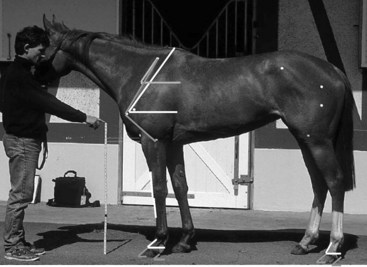

Two recent studies evaluated TBs and Quarter Horses (QHs) using skin markers, photography (three views: front, side, back), and computer-image analysis.15,16 Of the two studies done in TBs, one evaluated longitudinal development of conformation from weaning to 3 years of age. A strong relationship between long bone lengths and withers heights for all ages supported the theory that horses are proportional. Longitudinal bone growth in the distal limb increased only 5% to 7% and was presumably completed before the yearling year. Withers height, croup height, and length of neck topline, neck bottom line, scapula, humerus, radius, and femur increased significantly from age 0 to 1 year and age 1 to 2 years. Hoof lengths (medial and lateral, right and left) grew significantly from the ages of 0 to 1 and 1 to 2 years but decreased in length from age 2 to 3 years (presumably associated with trimming).15 Changes in growth measures indicated that growth rate either slowed or reached a plateau at 2 to 3 years of age. Horses also became more offset in the right forelimb between weaning and age 3, but the offset ratios did not change with age in the left forelimb. Shoulder angle increased in all age groups (becoming more upright), and this contributed to the increase in measured height at the withers. Dorsal hoof angle (both front and hind) decreased significantly from ages 0 to 1 and 1 to 2 years but did not change in the 2- and 3-year-old groups. This study provided objective information regarding conformation and skeletal growth in the TB, which could potentially be used for selection and recognition of important conformational abnormalities.15 Measurements of length and angle were obtained from photographs in which a tape measure was used for objective criteria and an objective method was developed for measuring offset knees (Figures 4-1 to 4-4).15

Fig. 4-2 Angle measurements (degrees) recorded from the left lateral view in a Thoroughbred study.15

(Reproduced with permission from Anderson TM, McIlwraith CW: Longitudinal development of equine conformation from weanling to age 3 years in the Thoroughbred, Equine Vet J 36:563, 2004.)

Little doubt exists that acquiring objective information is useful, not only to determine what is abnormal but also to define what is normal in a population. In both WBLs and STB trotters in Europe, toed-out conformation in the hindlimbs should likely be considered normal because a majority of both breeds have this conformational trait.10,12 These populations differed, however, in forelimb conformation. Few STB trotters had bench-kneed conformation, a finding supported by one of our (MWR) clinical observations that this conformational fault is highly undesirable in this breed (see Chapter 108). Recently, variation in conformation of National Hunt racehorses established guidelines with which individual horses could be compared and highlighted significant variations in horses with different origins (Irish and French horses differed significantly in girth and intermandibular width measurements).18 Circumference and length measurements were significantly associated with withers height. No underlying pattern of combinations of conformational parameters was found, but variations were identified between left and right measurements and in hoof, stifle angle, and coxofemoral angle measurements.18

Evaluation of Conformation

Balance

Balance is the way all parts of the horse fit together and is linked directly with assessment of lengths, angles, and heights. The horse should be proportional and thus well balanced. A horse may be visualized in thirds—the forehand, the midbody, and the hindquarters—by drawing three circles incorporating these areas (Figure 4-5). The circles should overlap but not excessively. Horses in good balance are likely to be superior athletes. Horses with a short, thick (throatlatch and shoulder regions) neck are often heavy and straight in the shoulders (Figure 4-6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree