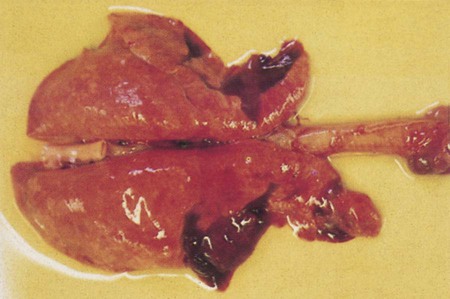

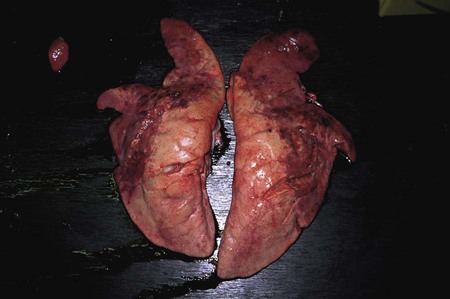

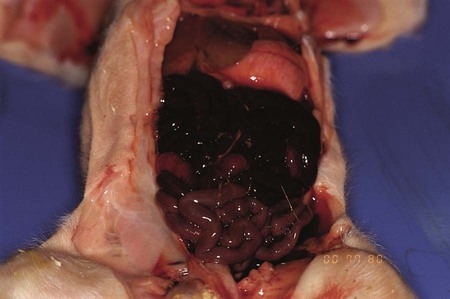

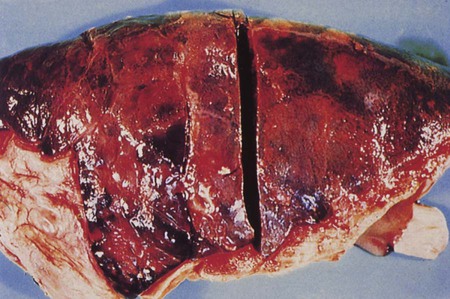

After reading this chapter, you will be able to • Describe and recognize clinical signs associated with specific diseases • Describe the etiology of the diseases • Describe common treatments of disease • List the common and scientific names of parasites associated with this species • List the common vaccinations and their schedules associated with this species Atrophic rhinitis is divided into two forms. The first form, regressive atrophic rhinitis, is caused by Bordetella bronchiseptica. It usually is mild and temporary, with little effect on performance (Fig. 25-1). The second form is progressive atrophic rhinitis, caused by toxigenic Pasturella multocida. Progressive atrophic rhinitis typically is severe and permanent, and it affects performance. Although each organism can cause nasal turbinate atrophy (Fig. 25-2) and nasal distortion independently, clinical signs tend to be more severe when combined. Although dogs, cats, and rodents can harbor B. bronchiseptica, their role in the spread of disease is unknown. Introduction of disease into a herd is usually through infected pigs. The disease can be intensified through overcrowding, mixing and moving of pigs, inadequate ventilation, and other concurrent diseases. Clinical signs usually appear in animals between 3 and 8 weeks of age and include sneezing, coughing, tear staining at the medial canthus of the eye, blockage or inflammation of the lacrimal duct, epistaxis, decreased performance, and deformation of the upper jaw (Fig. 25-3). Clostridium perfringens causes necrosis of all structural components of the villi. This necrosis causes blood loss into the intestinal wall and lumen (Fig. 25-4). These damaging effects cause necrohemorrhagic enteritis, which commonly causes hemorrhagic diarrhea (Fig. 25-5), followed by collapse and death in piglets younger than 1 to 3 days. When onset is less acute, brownish liquid feces develops between 3 to 5 days of age. Upon necropsy, the small intestine is often dark red and filled with hemorrhagic liquid. In piglets between 3 to 5 days of age, gas bubbles in the wall of the jejunum and necrosis of the mucosa within the jejunum and ileum can be seen. Enteric colibacillosis is caused by Escherichia coli. The bacteria colonize in the small intestine of nursing and weanling pigs. Because certain strains of E. coli produce enterotoxins that cause fluid and electrolytes to be secreted into the intestinal lumen, diarrhea is a common clinical sign (Fig. 25-6). Other clinical signs include rapid dehydration, acidosis, and death. Eperythrozoonosis is caused by Eperythrozoon suis, a rickettsial organism that typically appears as a coccoid organism. The organism is transmitted most commonly by lice (Fig. 25-7). Other forms of transmission are contaminated needles and surgical instruments. Clinical signs commonly include anemia, fever, pale mucous membranes, jaundice, emaciation, staggering or paralysis, weak neonates, unthrift appearances, and reproductive failure. Exudative epidermitis is also known as greasy pig disease. Infections are caused by Staphylococcus hyicus. The bacteria are unable to penetrate the skin and typically gain entry through lacerations on the legs and feet. Carriers tend to be the source of contamination in previously unaffected herds. Younger pigs tend to be more susceptible, but pigs gain immunity to the bacteria as they age. The main source of infection tends to be from sow to piglet during nursing. However, it can be spread through older more immune animals that carry the bacteria. Clinical signs include reddening of the skin, erosions at the coronary band, depression, and anorexia during early stages of the disease. As the disease progresses, the reddened areas of skin turn into brown spots, producing serum exudates that begin to cover the entire pig. As dirt builds up over the top of the sebum, it becomes black, giving a greasy appearance to the infected animal (Fig. 25-8). In the acute disease, death occurs within 3 to 5 days. Recovery from the disease tends to be time consuming, and decreased growth rates are common. Clinical signs of the disease include a fever of 104°F to 107°F, depression, difficult breathing, cough, and anorexia. Some pigs develop lameness associated with warm, tender, swollen joints. Pigs are capable of recovery, but chronic cases can lead to pericarditis and congestive heart failure (Fig. 25-9). The two most common bacterial serovars found in swine are Leptospira pomona and L. bratislava. Other serovars that have been reported in swine include L. canicola, L. tarassovi, L. muenchen, L. icterohaemorrhagiae, and L. grippotyphosa. In swine, the bacteria are commonly transferred upon exposure to infected urine from wildlife or other swine. Clinical signs include abortion 2 to 4 weeks before term, and SMEDI (stillbirth, mummification, embryonic death, and infertility). For more information on leptospirosis, see Chapter 13. Treatment and control of leptospirosis includes chlortetracycline and oxytetracycline if given early. Prevention includes annual vaccinations, confinement rearing, rodent control programs, fencing to prevent contact with contaminated water, and purchase of seronegative stock (Fig. 25-10). Mycoplasmal pneumonia is also described as “enzootic pneumonia” and “viral pneumonia.” It is typically caused by Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Mycoplasmal pneumonia is chronic but clinically mild. Clinical signs commonly include persistent dry cough, decreased growth rates, decreased feed efficiency, sporadic dyspnea, and a high incidence of lung lesions in slaughtered hogs (Fig. 25-11). Concurrent infections of other mycoplasmas, bacteria, and viruses that can increase the severity of the disease are common. Mortality is high in endemic areas, but morbidity remains low. Pigs of all ages can be affected. Infection usually occurs in the first few weeks of life through contact with the sow or gilt. Young pigs 3 to 5 months old tend to show the highest incidence of lung lesions. As pigs age, regression and recovery from the disease are seen. A high percentage (probably 99%) of commercial swine herds in the United States are believed to be affected. Once established in a herd, chronic clinical signs include intermittent coughing and decreased growth rates, which make detection difficult. However, severe internal damage still can be present and exacerbated by transport, overcrowding, and temperature changes, resulting in death. Concurrent infections of Mycoplasma, Pasteurella, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS), and swine influenza also are common. The pneumonia usually is bilateral, with pleurisy and pericarditis commonly seen (Fig. 25-12). Type 1 from group C randomly affects piglets up to 8 weeks of age (Fig. 25-13). Clinical signs in nursing piglets typically include polyarthritis and meningitis. Type 2 from group C tends to affect large, intensively managed herds, with transmission through carrier pigs or flies. Flies can travel 1 to 2 miles between farms and can carry the infection for up to 5 days. Type 2 commonly affects weaning pigs. Clinical signs of type 2 are fatal meningitis, abortion, depression, fever, tremors, incoordination, convulsions, bronchopneumonia, blindness, and deafness. Sudden death can occur from endocarditis or myocarditis.

Common Porcine Diseases

Bacterial Diseases

Atrophic Rhinitis

Clostridium Perfringens Type C Enteritis

Enteric Colibacillosis

Eperythrozoonosis

Exudative Epidermitis

Glasser Disease

Leptospirosis

Mycoplasmal Pneumonia

Pleuropneumonia

Streptococcal Infections

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Common Porcine Diseases