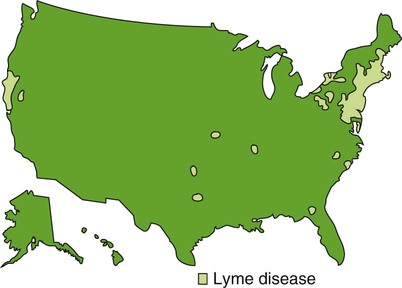

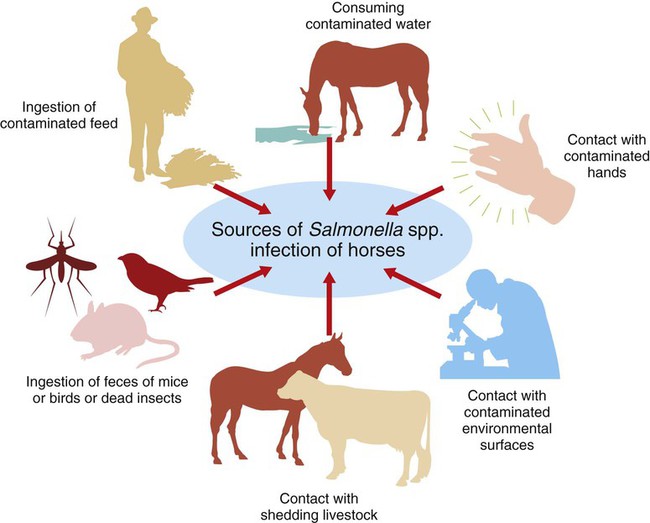

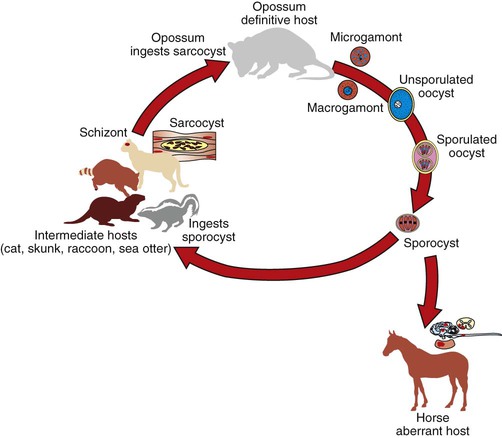

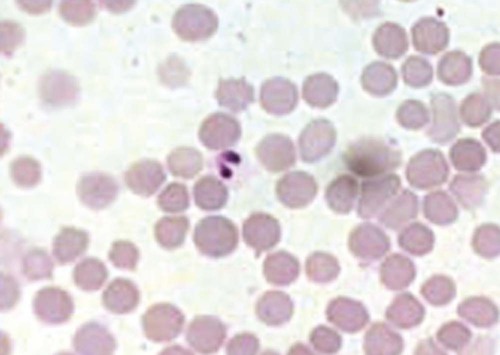

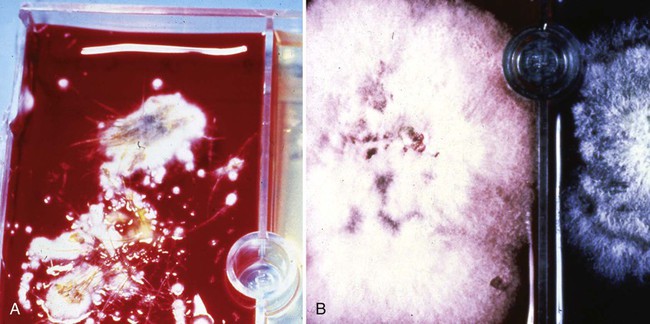

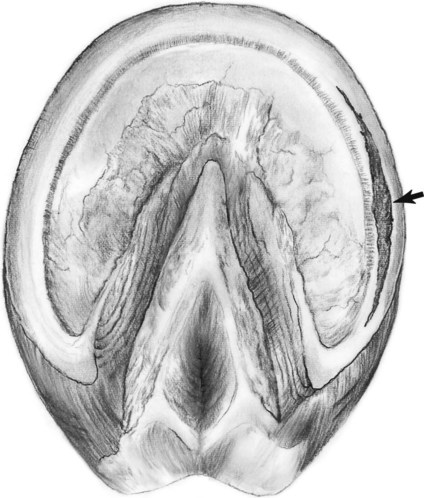

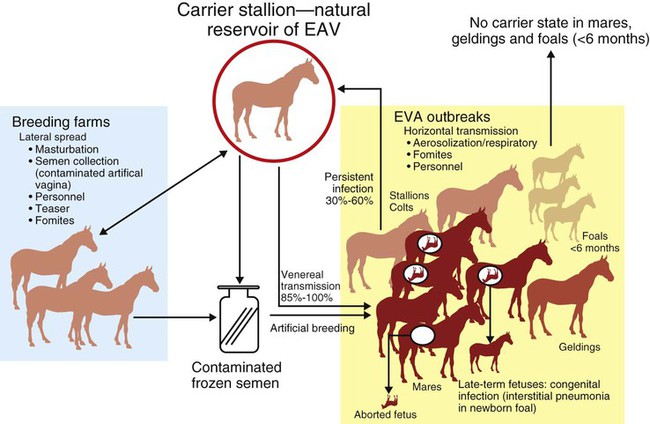

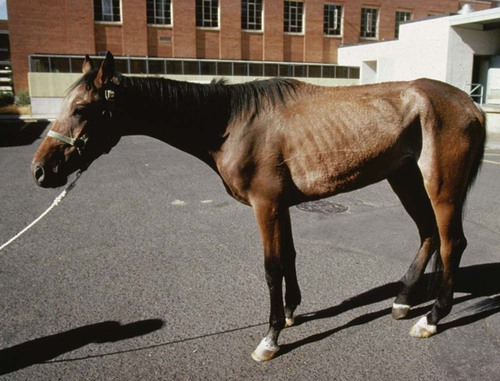

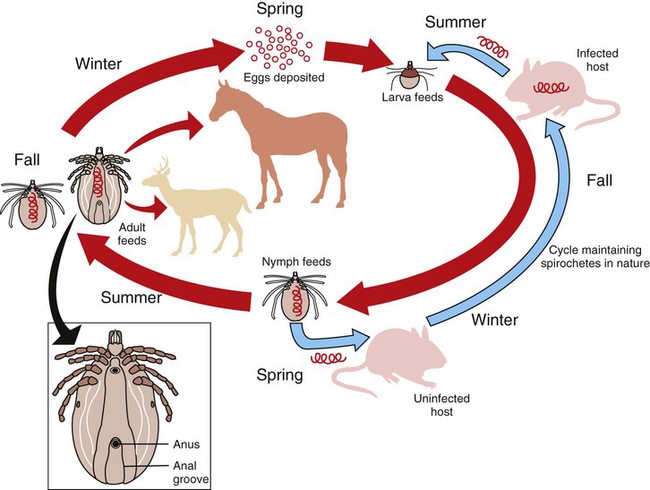

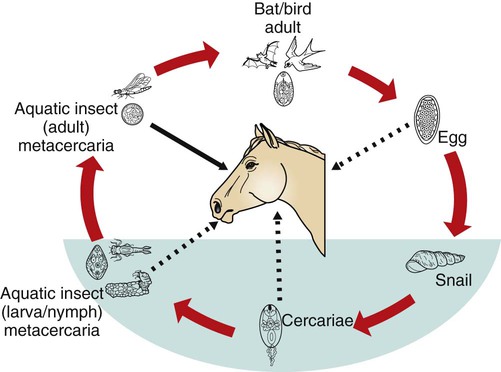

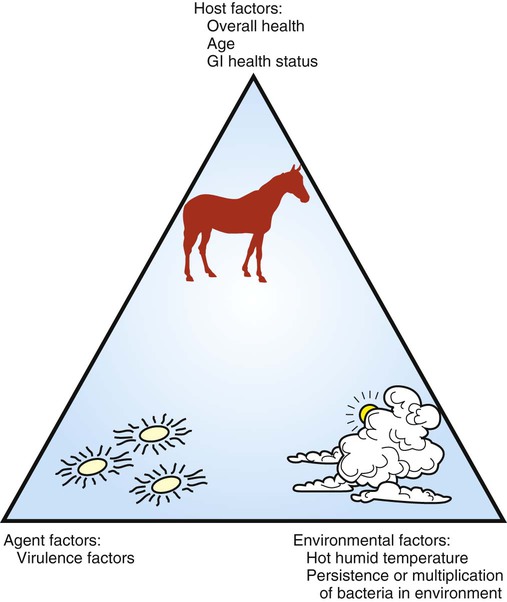

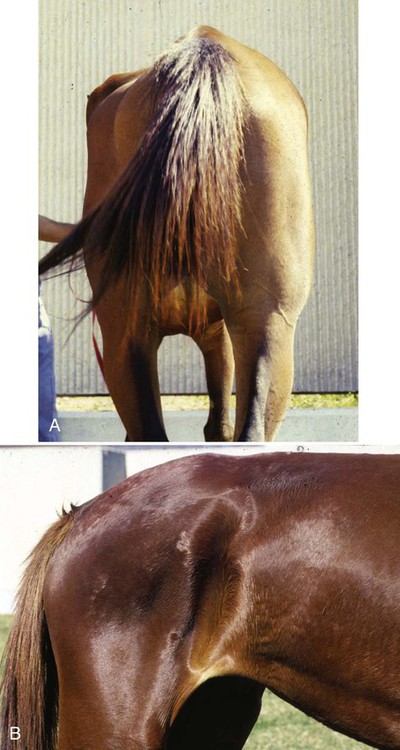

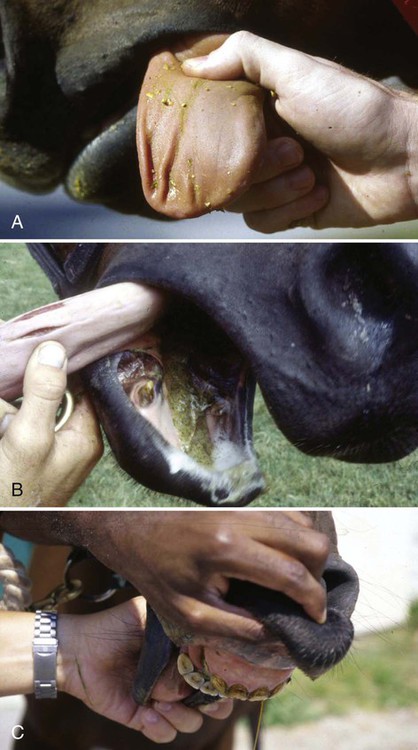

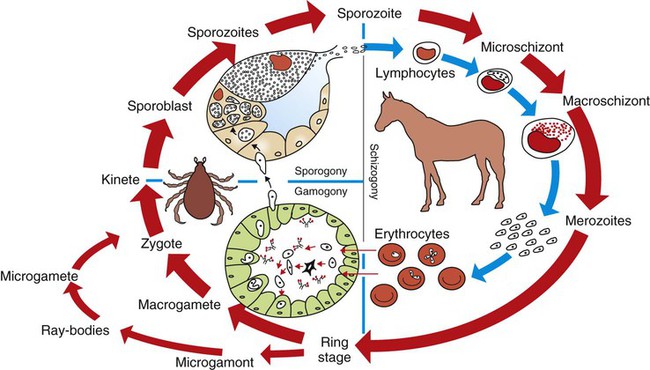

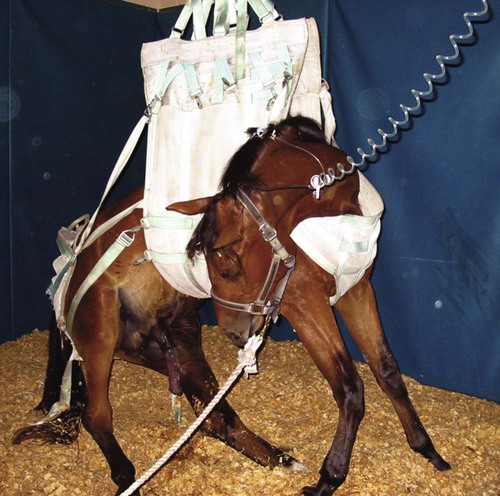

After studying this chapter, you will be able to • Describe and recognize clinical signs associated with specific diseases • Understand the etiology of the diseases • Understand and describe common treatments for disease • Know the common scientific names of parasites associated with this species • Know the common vaccinations and their schedules associated with this species Anthrax can affect all warm-blooded animals, including humans, and is discussed in Chapter 13. Clinical signs include a creeping paralysis that usually begins at the head and moves caudally (Fig. 9-1). Veterinarians diagnose botulism with identification of C. botulinum in the feces, blood, or feed that was ingested. Treatment is generally supportive but may include attempts to flush the toxin from the gastrointestinal tract using gastric lavage or purgatives. Mortality is often high due to respiratory paralysis (Fig. 9-2). Equine canker is a chronic hypertrophic, moist pododermatitis of the epidermal tissues of the foot (Fig. 9-3). The most commonly isolated agents include Fusobacterium necrophorum and one or more Bacteroides spp. The disease is often seen in the southern states and the Midwest. The exact cause of canker is unknown, but most horses affected by canker have a history of being housed in wet areas year round. Lameness usually does not present until the corium is involved. Equine canker has a characteristic odor. The frog usually is very friable and has a cottage cheese–like appearance. Treatment often involves superficial debridement and topical antimicrobial agents (Fig. 9-4). Lyme disease is caused by at least three strains of Borrelia burgdorferi, a gram-negative, unicellular spirochete with flagellar projections. Borrelia burgdorferi does not live long outside of its host. The bacterium follows a 2-year enzootic life cycle that involves ixodid ticks and mammals (Fig. 9-5). The primary vector for the disease is the deer tick. The female is the most likely competent vector. Other ticks associated with the disease include the black-legged tick and the western black-legged tick. Infection of the horse occurs when a tick attaches to a horse for longer than 24 hours. For successful transmission of the bacteria, the tick must be attached for at least 24 hours and sometimes up to 48 hours. The organism lives in the tick’s gut and is transferred as it feeds on the blood of the horse. Lyme disease is most prevalent in regions of high humidity and dense vegetation (Fig. 9-6). Although Lyme disease can occur during any time of the year, most cases occur from May through August in the North Central and Pacific coast states. Neorickettsia risticii lives inside trematodes (flukes) that infect snails. When the trematodes release their larvae and enter a water environment, the larvae are infected with N. risticii. The larvae of the caddis and mayfly, which also live in water, consume the infected trematode larvae and become infected with N. risticii themselves. When the caddis and mayfly larvae hatch, they are infected with N. risticii. If a horse then accidentally eats one of the flies, the horse becomes infected (Figs. 9-7 and 9-8). The bacteria will begin to replicate inside the gastrointestinal tract of the horse, causing the clinical signs of depression, diarrhea, fever, toxemia, abortion in pregnant mares, and sometimes laminitis. The condition can affect animals of all ages and presents as crusty scabs or matted tufts of hair. The lesions are usually found on the head, neck, and chest (Fig. 9-9). Yellow or green pus can be found underneath larger scabs. A definitive diagnosis is made from culture and identification of D. congolensis. Horses infected with salmonella can have one of three types: carrier, mild clinical, or acute clinical. Carrier horses are subclinical carriers that intermittently shed the organism. If a carrier horse is stressed, the horse may develop clinical signs. Horses that develop the mild clinical form of the disease develop pyrexia, anorexia, depression, and a soft watery diarrhea (Fig. 9-10). Horses with this form of salmonella infection often display clinical signs for 4 to 5 days but shed the organism in their feces for days to months after the infection. The third form of the disease, acute clinical, causes a watery, foul-smelling diarrhea, abdominal pain, severe depression, anorexia, and a pronounced neutropenia. Horses with this form of infection often dehydrate quickly, causing electrolyte imbalances and, with prolonged diarrhea, enterocolopathy and bacteremia. Horses left untreated with the acute clinical form of the disease have increased likelihood of death. Salmonella infections, both the mild clinical and acute clinical forms, should be treated with IV fluid and electrolyte replacement. The use of gastrointestinal protectants and antibiotics is controversial. NSAIDs are given to help counteract the effects of endotoxins and to control pain. In severe causes, administration of equine plasma may be indicated to correct hypoproteinemia. The plasma may also provide specific antibodies to the endotoxin and provide coagulation factors. Due to the zoonotic risk and contamination of other horses with Salmonella, clients and other facility staff must be educated on the importance of quarantine. Prevention of Salmonella can be difficult because Salmonella is present in the environment (Figs. 9-11 and 9-12). A horse with strangles often presents with a sudden fever, mucopurulent nasal discharge (Fig. 9-13), and abscessation of the submandibular and retropharyngeal lymph nodes (Figs. 9-14 and 9-15). Younger horses are more likely to develop more severe lymph node abscessation, which extends the recovery period. The submandibular and retropharyngeal abscesses may make it difficult for the horse to swallow. Some horses may become listless or anorexic. Diagnosis of strangles is performed with culture of nasal swabs, pus from an abscess (Fig. 9-16), or nasal washes. Other forms of diagnosis can include polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and serology. Tetanus is caused by endotoxins produced by the bacterium Clostridium tetani. Clostridium tetani is a motile, anaerobic, gram-positive bacillus. The most common cause of infection is contamination of wounds (Fig. 9-17). Puncture wounds that contain rusty metal, dirt, or manure are particularly likely to cause infection. Contaminated surgical incisions and umbilical structures may also lead to tetanus infections. The incubation period of tetanus ranges from 1 to 60 days but usually averages between 7 and 10 days. The disease begins with generalized stiffness. With mild infections the stiffness may remain localized in the head and neck. Stiffness leads to the characteristic stance known as the “sawhorse appearance” (Fig. 9-18), in which the head, neck, back, and legs are stiff and the tail head is elevated. In some more severe cases, the horse may even be recumbent, and dyspnea may be seen. Diagnosis is often based on clinical signs. Equine protozoal myeloencephalitis (EPM) is most commonly caused by the protozoan Sarcocystis neurona, but it also can be caused by the protozoan Neospora hughesi. Sarcocystis neurona is the most common cause of EPM. In the United States the only definitive host for S. neurona is the opossum, although armadillos, raccoons, cats, and skunks have been identified as natural intermediate hosts. Transmission of the disease occurs when horses consume sporocysts in opossum feces (Fig. 9-20). Clinical findings of EPM vary greatly depending on the localization of the parasite. Asymmetric muscle atrophy is a common clinical sign of EPM that often affects the quadriceps and gluteal muscles (Fig. 9-21). The horse may show signs of cranial nerve abnormalities, such as atrophy of the tongue, self-mutilation of the tongue, and recumbency (Fig. 9-22). The life cycle of B. caballi begins when an infected tick feeds on a naive horse. The most common tick for transmittal of B. caballi is Dermacentor nitens. The sporozoites immediately invade the erythrocytes, and within the erythrocytes the parasites develop from a small anaplasmoid body (trophozoites) into a large pyriform body (merozoites). The cycle then continues when a naive tick feeds on the horse and ingests the infected erythrocytes. Most of the trophozoites are destroyed in the midgut of the tick but the merozoites survive, allowing the new tick to infect another horse. The life cycle of B. equi is similar to B. caballi except for transovarial transmission within the tick and the possible addition of a preerythrocytic stage within lymphocytes (Figs. 9-23 and 9-24). Clinical signs include pyrexia, depression, anemia, thirst, and eye problems (Fig. 9-25). The urine is yellow to reddish in color. Mortality is 10% to 15%. Prevention involves tick control and sterilization of needles and medical instruments between uses. Treatment of adult horses with acute clinical signs involves administration of imidocarb dipropionate, diminazene, amicarbalide, euflavine, and/or tetracyclines. Prevention of the disease should include restriction of movement of infected horses and tick feeding prevention (Fig. 9-26). Dermatophytosis is also known as ringworm. It is a common superficial cutaneous fungal infection caused by keratinophilic fungi that invade the stratum corneum of the skin and other keratinized structures. Trichophyton equinum is the most common agent that causes ringworm in horses (Fig. 9-27). Other agents include Trichophyton verrucosum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Microsporum canis, Microsporum equinum, and Microsporum gypseum. Ringworm is highly contagious and is spread by direct or indirect contact. Indirect contact includes sharing tack, stalls, feed and water containers, and insects. The fungus can survive on these items for up to 12 months. Clinical signs include small round lesions covered with small scales (Fig. 9-28). The hair often breaks off just above the skin level. Older lesions may heal in the center, but the edges are quite active. Identification of ringworm can be made with a Wood lamp or by culture or histology (Fig. 9-29). White line disease is caused by the invasion of bacteria, fungus, or yeast into the inner horn. When the infection results from fungus, it is also called “onychomycosis.” The affected area of the hoof fills with a cheesy material and air pockets that are often packed with debris (Figs. 9-30 and 9-31). The infection starts at the ground and, if left untreated, can migrate to the coronary band. Clinical signs are often similar to those of laminitis. The horse may be lame, or its sole may be warm to the touch. Sometimes the pockets are filled with a black, foul-smelling substance similar to thrush. Treatment involves resection of the underlying hoof wall and topical application of an antiseptic. Eastern equine encephalomyelitis and Western equine encephalomyelitis both are found throughout North America. Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis is most commonly found in the southern United States and in countries further south. Encephalomyelitis is transmitted by the mosquito. Common clinical signs include fever, ataxia, anorexia, paralysis, circling, head pressing, and hyperexcitability (Fig. 9-32). Equine viral arteritis is caused by equine arteritis virus (EAV). EAV causes flu-like symptoms, abortion, and, in very young horses, pneumonia. The disease is transmitted through either respiratory particles or venereal routes (Fig. 9-33). Even though horses can transmit the disease through bodily fluids (e.g., urine), aborted fetuses, and aerosol, infected semen is the primary source of infection. Semen from infected stallions can be chronically or acutely infected with the virus. The stallion is the natural reservoir for the virus. The incubation period is 2 to 14 days. Clinical signs of EIA vary depending on the virus strain and the susceptibility of the horse. Acute EIA is caused by a virulent strain of EIA. The incubation period ranges from 5 to 30 days. When clinical signs present, the horse often develops a fever, becomes lethargic, and is anorexic (Fig. 9-34). The mucous membranes appear pale and may have petechiae. The animal may be icteric, and neurologic signs may develop (Fig. 9-35). Blood analysis reveals thrombocytopenia and anemia. There is no specific therapy for horses diagnosed with EIA. The disease is reportable in the United States. Most often the horse is recommended for euthanasia. If the owner elects not to euthanize, the animal must be quarantined from other horses, the horse cannot undergo travel interstate, and supportive therapy is recommended (Fig. 9-36).

Common Equine Diseases

Bacterial Diseases

Anthrax

Botulism

Canker

Lyme Disease

Potomac Horse Fever

Rain Rot

Salmonella

Strangles

Tetanus

Other Microbial Diseases

Equine Protozoal Myeloencephalitis

Piroplasmosis

Dermatophytosis

White Line Disease

Viral Diseases

Encephalomyelitis

Equine Arteritis

Equine Infectious Anemia

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Common Equine Diseases