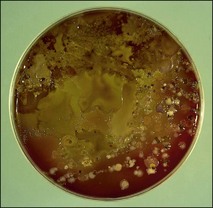

Chapter 1 • Samples should be taken from the affected site(s) as early as possible following the onset of clinical signs. This is particularly important in viral diseases as shedding of virus is usually maximal early in the infection. This is also true of enteric bacterial pathogens. • It is useful to collect samples from clinical cases and in-contact animals, particularly if there has been an outbreak of disease. In-contact animals may be at an earlier stage in the infection with a greater chance of them shedding substantial numbers of microorganisms. • Samples should be obtained from the edge of lesions and some macroscopically normal tissue included. Microbial replication will be most active at the lesion’s edge. • It is important to collect specimens as aseptically as possible, otherwise the relevant pathogen may be overgrown by numerous contaminating bacteria (Fig. 1.1). In certain circumstances a guarded swab should be used to bypass an area with a large population of normal flora. Figure 1.1 Grossly contaminated blood agar plate demonstrating the need to collect specimens as carefully as possible. • The laboratory should be informed if treatment has commenced in order that counteractive measures may be taken to increase the possibility of isolating bacteria or that an alternative method of detection such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may be employed. • When possible a generous amount of sample should be taken and submitted, such as blocks of tissue (approximately 2 cm3), biopsy material, or several millilitres of pus, exudate or faeces. For serology, at least 5 mL of blood should be obtained to allow a number of tests to be carried out if necessary and to allow the sample to be stored and tested with subsequent samples. • Cross-contamination between samples must be avoided. This is essential where a highly sensitive amplification technique such as PCR is to be used for the detection of the aetiological agent. • Precautions must be taken to avoid human infection where a zoonotic condition is suspected. Tissues from outside the body cavities should be collected first followed by tissues from the thorax and then the abdomen. Sterile instruments should be used to collect tissue samples of at least 1 cm3 which should then be placed in separate sterile screw-capped jars (Fig. 1.2). If the laboratory is some distance away tissue may be forwarded in virus or bacterial transport medium. It is important to remember that virus transport medium usually contains antibiotics thus rendering the sample unsuitable for bacterial examination. Tissue for histopathological examination should be placed in at least 10 times its volume of neutral buffered 10% formalin. Fluids are preferable to swabs as the greater sample volume increases the likelihood of detecting the causal organism. Samples for agent isolation should be placed in sterile containers. Viruses and many bacteria are susceptible to desiccation especially if collected on a dry swab. Formulae for suitable transport media for viruses, chlamydia and other organisms are given in Appendix 2. Whenever possible the sample should be collected from the specific site of infection. The usual short cotton wool swabs are generally unsatisfactory for obtaining nasopharyngeal specimens of epithelial cells and mucus for the investigation of respiratory disease of large animals. Guarded swabs are necessary for certain bacteriological examinations where misleading results could be generated due to contaminants from adjacent sites that are colonized with bacterial flora. Similarly, fungal organisms from the environment readily contaminate the nasal passages and upper trachea. The diagnostic laboratory should be consulted before collecting samples for the isolation of specific pathogens that require specialized media or culture conditions, for example, Taylorella equigenitalis, Chlamydophila psittaci or Mycoplasma species. The laboratory will either supply specialist swabs and transport media or recommend a reputable source, as appropriate.

Collection and submission of diagnostic specimens

General Principles for Sample Collection

Tissue

Swabs and discharges

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Collection and submission of diagnostic specimens

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue