Peter R. Morresey

Colic in Foals

Diagnosis of abdominal pain in the foal can be challenging because of the large number of potential causes that exists. Physical examination, findings from more advanced or targeted examinations, consideration of the more common causes, and response to treatment allow the list of differential diagnoses to be abbreviated. Hypovolemia, cardiovascular compromise, and the requirement for adequate analgesia must be addressed during the diagnostic workup. Making the decision for surgical intervention can be problematic because it is important to avoid an unnecessary procedure. However, delaying surgery when it is required has a direct bearing on the prognosis.

Signalment

The differential diagnosis of abdominal pain is affected by foal age. Congenital abnormalities usually become apparent within hours of delivery. Meconium impactions first manifest as abdominal pain in the first 24 to 48 hours of life. Uroperitoneum may cause discomfort in the range of 2 to 5 days of age. Older foals, but occasionally neonates, may have small intestinal volvulus, colon displacement, intussusception, and gastric ulceration. Peritonitis resulting from leakage of intestinal contents (such as from a perforated gastric or duodenal ulcer or adhesions from urachitis) may also occur. Nongastrointestinal causes of abdominal pain include fractured ribs, uroperitoneum, neurologic compromise, and, rarely, pleuritis and pneumothorax.

History

Information pertinent to the cause of the foal’s apparent abdominal pain may vary with the foal’s age at onset of the abdominal pain. In newborn foals, prepartum compromise in the dam, an abnormal pregnancy, or events at delivery can all lead to hypoxic insult in the foal. Regarding the neonatal foal in early life, passage of meconium, suckling activity, and production of appropriate feces should be noted. Colic may precede the onset of diarrhea, and information about concurrent and previous fever, diarrhea, and colic episodes in foals on the farm should be obtained. Management changes and the use of antimicrobials may also precipitate gastrointestinal disturbances.

With regard to the affected foal, the time course of the apparent abdominal pain is important. If pain has been long-standing or gastrointestinal pathology is significant, severe depression may develop in association with exhaustion or systemic compromise. Clinical signs, if any, occurring concurrently with the apparent abdominal pain should also be considered. For example, bruxism is considered an indication of abdominal discomfort but is also associated with gastroduodenal ulcers.

Examination of the Foal with Suspected Abdominal Pain

The decision that most affects prognosis in a colicky foal and that must be made in a timely fashion is whether a surgical or nonsurgical lesion exists. The neonatal foal may not respond to systemic compromise as noticeably as adult horses. This necessitates rapid diagnosis and prompt resolution of any strangulating intestinal lesions. Apparent abdominal pain in the foal may develop from a minor condition, such as skin irritation that causes rolling, but can also be caused by life-threatening intestinal lesions, such as intestinal volvulus. As with any diagnostic workup, a complete physical examination in combination with ancillary tests is required to help distinguish between the many surgical and nonsurgical causes of colic.

Observe From a Distance

When it is possible, observing the foal from a distance greatly augments the physical examination. Consideration must be given to the severity and duration of pain. If abdominal pain is severe and uncontrollable, the workup should proceed more rapidly. Use of chemical restraint may override the true character of the abdominal pain. The particular nature of the pain may be suggestive of the source: rolling into and lolling in dorsal recumbency (suspect gastric ulceration; Figure 181-1), dropping to the ground in one rapid motion (intestinal pathology), and straining to defecate (impaction) or urinate (uroperitoneum) may all help direct diagnostic testing.

Besides information regarding the etiology and characteristics of the abdominal pain, other differential diagnoses, including musculoskeletal trauma, neurologic disorders (seizure activity), or neuromuscular pathologies (botulism), may be supported.

Nature of the Pain

Foals are less tolerant of abdominal pain than adult horses. Therefore the severity of pain in a foal is neither a sensitive indicator of the severity of abdominal disease nor specific for the cause of colic. Abdominal pain results from stimulation of stretch-sensitive receptors in the mesentery, stretching of the serosal surface, and edema in the intestinal wall caused by inflammation or ischemia. Mild signs of colic, which may be persistent or may progress to more severe abdominal pain, are compatible with a diagnosis of enteritis, gastroduodenal ulceration, or a simple intraluminal obstruction. The same pathophysiologic mechanisms are involved in pain resulting from enteritis or a strangulating or nonstrangulating obstruction. Unremitting pain that is unresponsive to analgesics is more consistent with a strangulating lesion that will necessitate surgical correction.

When alterations in intestinal motility are present, decreased strength or frequency of contractions results in accumulation of ingesta and gas. The resulting intestinal distension leads to stimulation of stretch mechanoreceptors in the gut wall, resulting in pain.

Physical Examination

Vital signs may not always differentiate between surgical and nonsurgical causes of colic. Fever is suggestive of the early stages of sepsis (gastrointestinal) or of intestinal pathology. Hypothermia is suggestive of severe systemic compromise and may indicate necrotic bowel or advanced peritonitis and sepsis. With severe abdominal pain, high heart and respiratory rates are to be expected. Marked, persistent tachycardia should suggest a surgical lesion. Dyspnea warrants closer investigation of the thoracic cavity.

Auscultation

Increased gut activity is seen in conditions that irritate the intestinal tract, and the outcome of these conditions is usually favorable. Alternatively, reduced or nonexistent intestinal activity may indicate a more serious situation. Hypoperistalsis may be caused by sudden feed changes, carbohydrate overload, or infectious agents. If gut sounds are decreased, fecal production is scant, and signs of acute pain are present, a less favorable prognosis should be expected.

Mucous Membranes

Changes in mucous membrane color can indicate shock (from endotoxemia, septicemia, or splanchnic ischemia) and can be seen in a number of gastrointestinal diseases. Severely toxic membranes should prompt suspicion of a strangulating lesion, but severe, acute bacterial enteritis and peritonitis can also be associated with this sign.

Dehydration or Hypovolemia

Fluid loss or lack of intake leads to dehydration and diminished circulating blood volume. This is seen as prolonged skin tenting time, dry mucous membranes, a high heart rate, diminished peripheral pulse intensity, and cool extremities. If not corrected, electrolyte alterations and acid-base disturbances arising from compromised perfusion become evident.

Abdominal Size and Shape

Gross abdominal distension is indicative of gas or fluid accumulation in the intestinal tract or stomach. Distension noticed predominantly in the left craniolateral part of the abdomen suggests gastric distension, and a prompt assessment should be made by ultrasonography or nasogastric tube passage.

Nasogastric Intubation

Used as both a diagnostic and therapeutic technique, nasogastric intubation may provide additional information useful in developing a differential diagnosis. The relief of pain and rapid resolution of tachycardia after intubation indicate that gastric distension is one of the causes of pain, and immediate and long-lasting colic resolution suggests a medical condition. Moderate volumes of reflux can be obtained from foals with enteritis and the possibly accompanying small intestinal ileus. Persistent reflux suggests severe small intestinal obstruction caused by a volvulus, stricture, or intussusception.

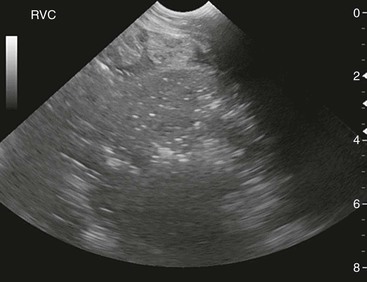

Abdominal Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography has the advantage of being a rapid, noninvasive diagnostic aid. In the foal, a large part of the abdominal content can be imaged quickly, allowing therapeutic interventions during the initial case workup. Considerable knowledge of normal anatomy is required to clinically interpret findings in a useful fashion.

Characterization of small intestinal motility (as ileus, normal, or increased in frequency), intestinal distension (minimal, moderate, or marked), and wall thickness (normal or increased) is possible. In the healthy foal, small intestinal loops appear flaccid and fluid filled. Ileus, enteritis, or small bowel obstructive diseases cause these loops to become rounded and to increase in size. As foals age, small intestinal imaging may become limited to the inguinal region because of normal age-related changes in the stomach and colon.

In cases of large intestine gas distension, reflection of sound waves causes a poor ultrasonographic view of the abdomen, making interpretation of deeper structures difficult.

Excessive peritoneal fluid may indicate peritonitis, a ruptured viscus, or uroperitoneum. The character of the abdominal fluid (anechoic or turbid) can be identified, with increasing echogenicity associated with increased cellularity.

Laboratory Findings

In the initial stages, no clinicopathologic abnormalities may be apparent. With the onset of sepsis or intestinal devitalization, leukopenia and neutropenia may be seen. Inflammation associated with long-standing problems will be reflected in an increase in fibrinogen concentrations and leukocytosis. Dehydration may lead to increased creatinine, protein, and lactate values, although albumin may be decreased if intestinal inflammation is present. Electrolyte abnormalities may occur with diarrhea and with uroperitoneum. If inflammation of the peritoneal cavity is widespread or endotoxemia is present, serum activities of muscle and liver enzymes may be high. Blood glucose may be increased by stress or endotoxemia, or decreased by inappetence or endotoxemia.

Peritoneal Fluid Analysis

Collection of peritoneal fluid can be difficult in the foal and should be performed with adequate restraint and ultrasonographic guidance. Enterocentesis is more likely to occur as a complication of this procedure in foals than in adult horses, and the consequences of intestinal perforation may be severe in young foals. Paracentesis is not as routine a procedure in foals as it may be in certain colic presentations in adult horses, and the veterinarian should have compelling indications for obtaining this type of sample from a foal.

Peritoneal fluid usually has a normal composition in foals with enteritis or early intestinal obstructions in which devitalization of the intestinal wall has not begun. As these diseases progress, increases in peritoneal fluid cell count and protein can occur, but not to the extent of that seen with strangulating obstructions. Strangulating lesions of any duration are associated with high nucleated cell count and protein concentration. In animals with a ruptured viscus, intracellular bacteria, plant material (in older foals), and degenerative neutrophils may be identified in the peritoneal fluid.

Abdominal Radiography

Given the smaller size of the foal, excellent views of the intraabdominal viscera can be obtained with plain radiographs. This technique has been superseded to a large degree by the ready availability of ultrasonography, but radiography is invaluable in some situations, aiding in determining the location, but not necessarily the cause, of intestinal gas or fluid distension. Gaseous distension of the small intestine is seen in foals with enteritis, peritonitis, or small intestinal obstruction and is characterized radiographically by multiple intraluminal gas–fluid interfaces. Upper gastrointestinal contrast studies are indicated to evaluate potential duodenal stricture (see Gastric Outflow Obstruction and Gastroduodenal Ulcer Disease) or to evaluate motility disorders.

Large bowel distension may be seen with colitis. During obstruction, the large intestine is markedly distended and becomes displaced within the abdomen. Contrast studies using gravity barium enemas are useful in identifying the presence and location of meconium impactions in the terminal colon or rectum.

Gastroscopy

Gastroscopy is invaluable for the diagnosis of gastric ulceration and monitoring of response to treatment. The esophagus can also be imaged if reflux esophagitis is suspected. Because some choke episodes present with apparent colic, visual detection of any esophageal obstruction is diagnostic.

Causes of Abdominal Pain in the Foal

Conditions resulting in pain in the neonate overlap those conditions causing abdominal pain in the older foal; therefore they will be considered as a continuum. A few conditions are specific to the neonate.

Meconium Retention or Impaction

The initial passage of meconium usually begins in the first few hours after birth. Meconium is generally completely passed within the first 24 hours of life, but it can take up to 48 hours for complete voiding of this material. Passage of milk feces indicates the obstruction has passed. Abdominal pain associated with meconium impaction can be mild to severe, with repeated straining efforts and increasing distress observed. Trauma to the terminal colon and bladder may result, with devitalization of the affected tissue potentially leading to peritonitis and, in the case of the bladder, uroperitoneum. Meconium retention occurs higher in the intestinal tract than meconium impaction and involves the transverse or right dorsal colon, or the small colon. Contrast radiography with a barium enema can be diagnostic for presence and location of impaction. Ultrasonography can also confirm meconium within the intestinal tract in smaller neonates or when close to the abdominal wall (Figure 181-2).

Congenital Defects

The accepted pathogenesis of intestinal atresia centers on an ischemic vascular event affecting the involved segment of the gut during gestation. This curtails growth and causes atrophy of the affected segment. A typical presentation occurs within the first 2 to 48 hours of life, manifesting as progressive abdominal distension and pain. Meconium is not produced. Surgical exploration is required to ascertain the location and severity of the defect, and the prognosis is guarded to poor.

Intestinal aganglionosis is most commonly encountered in lethal white foal syndrome, an autosomal recessive condition affecting the American Paint Horse. Foals are predominantly white in color, being the progeny of an overo–overo mating. Colic appears within 12 to 24 hours of birth, and because no therapy is available, euthanasia is indicated. Caution should be exercised because not all white foals have lethal white syndrome.

Acute respiratory distress in association with the onset of colic signs has been reported in one foal. In that case, a diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia was made by use of radiography and ultrasonography. Necropsy findings suggested the diaphragmatic defect was congenital in origin. Traumatic diaphragmatic rupture (laceration by the free end of a fractured rib) is also possible.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree