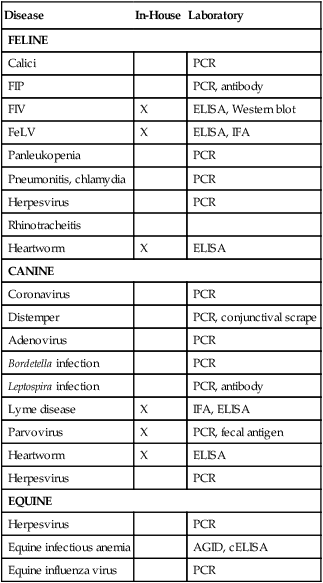

CHAPTER 23 Mastery of the content in this chapter will enable the reader to: • Identify common diseases and vaccinations. • Define diagnostic equipment and procedures. • Explain the importance of preanesthetic procedures. • Explain the importance of labeling medications. • Explain to owners how to administer medications. • Define the nutritional needs of puppies and kittens. • Differentiate therapeutic diets based on characteristics. It is the responsibility of all team members, but especially veterinary assistants and technicians, to check the patient into a room and obtain a complete history from the client. Chapter 14 provides detailed instructions on how to take an accurate history. It is very important to know if a pet has been vomiting or has diarrhea, how long it has had the presenting symptoms, and whether the owner can correlate any symptoms with abnormal events. The history taker must write down all the information provided by the owner; the details may provide a valuable tool for the doctor as an attempt is made to make a diagnosis. A good history taker is a valuable asset to the practice. If a muzzle is needed at any time, team members should not hesitate to use it (Figure 23-1). Muzzles are made to protect team members from being bitten! Some owners may argue that their pet does not need a muzzle; however, for everyone’s safety, including the owner’s, muzzles should be used. Both dog and cat muzzles are available and come in a variety of sizes. Muzzles should fit snugly on a dog’s nose. If the dog can open its mouth, the muzzle is too large, and the purpose of the muzzle is defeated. Cat muzzles should fit snugly over the entire head. Cat bags and towels may also be helpful to prevent team members from becoming scratched (Figure 23-2). The full cat body is placed inside the bag with only the head exposed. Most bags have two small openings that will allow front legs to be pulled through if needed. virus or bacteria that has been passed through a culture to reduce its virulence, whereas a killed vaccine introduces an inactivated virus into the body. Recombinant vaccines are available in two types. The first is the subunit vaccine, produced by a microorganism that has been engineered to make a protein, which then elicits an immune response in a target host. Another is the recombinant vector type, in which harmless genetic material from a disease-causing organism is inserted into a weakened virus or bacterium (the vector). When the vector organism replicates, the genetic material that was inserted elicits the desired immune response. A variety of combinations of vaccinations are available on the market; the preference rests with the veterinarian as to which combination to order. It is highly recommended to indicate in the medical record where the vaccine was given. Some vaccines may cause localized reactions, and if the location of administration has been documented in the record, vaccine reaction can be ruled in or ruled out. Stamps are available to chart the location easily (Figure 23-3). Boxes 23-1 through 23-3 are not a complete list of diseases, but rather a summary of diseases for which there are vaccines. A brief description of the disease and symptoms is also included. Some tests are available for in-house diagnostics to determine if a pet has a disease, whereas other tests need to be submitted to an outside laboratory for diagnostics. Table 23-1 summarizes tests available for diagnostics. Table 23-1 Tests Available for Common Diseases Laboratory tests may include in-house bloodwork or panels sent to an outside laboratory (see Chapter 9). In-house lab work may consist of complete blood count (CBC) and chemistries (both abbreviated and complete panels are available), heartworm tests, fecals, urinalyses, cytologies, FeLV/FIV tests, and parvovirus tests. A variety of companies produce a number of tests that are available for use in practice; the product insert should be used as a guide to completing each test correctly. Directions that are not followed correctly can yield inconclusive results, producing a false-positive or –negative result. Not only does this provide substandard medicine, it decreases the profits of the veterinary practice. Any failed tests should be repeated and reported to the practice manager in case the tests are tracked. It is imperative for the veterinary assistant and technician to become familiar with general tests that are run in-house. Clients will ask what test correlates with what bodily system, and these questions must be answered clearly and confidently. Table 23-2 lists the names of common tests and the system with which the test correlates. Table 23-2 Urine samples can provide a wealth of information for the veterinarian, and several tests can be performed on one sample. Most urine samples are obtained by free catch; either the owner has obtained a sample or an assistant has walked the dog and caught a midstream urine sample (Figures 23-4). Other methods of collection include cystocentesis or catheterization (Figure 23-5). If a urine sample will be sent to the laboratory for culture, a sample acquired by cystocentesis is highly recommended because it is a sterile sample that is obtained without any contamination. Cystocentesis is the process of inserting a needle into the bladder and withdrawing a sample. The tests that can be completed on urine are numerous; the most common tests completed in the hospital include specific gravity, stick urinalysis, and sediment (Boxes 23-4 and 23-5). The specific gravity provides the concentration of the urine and is a key indicator of how well the kidneys can concentrate the urine. Certain disease processes can affect the concentration, including renal disease and diabetes. A stick urinalysis is performed by dipping a urinalysis stick into the sample itself (if it is a sterile sample, the urine should be dropped onto each testing block) (Figure 23-6). The sediment is essential to verify the information provided by the stick. Electrocardiograms, often referred to as EKGs or ECGs, are recordings of the heart’s electrical activity. The recording traces the entire heartbeat process, through both the systolic and diastolic phases. Arrhythmias and conduction disturbances of the heart can be detected on ECGs, and an ECG is highly recommended before administering anesthesia to patients (Figure 23-7). Care must be taken when taking radiographs. Safety cannot be emphasized enough. Studies indicate that excess radiation causes cancer, birth defects, a decreased life span, and fertility issues. Protection must be worn at all times while taking radiographs (Box 23-6 and Figure 23-8). Lead thyroid collars, gowns, and gloves are the absolute minimum that should be provided to all team members allowed to take radiographs. Eye goggles are also a good idea (eyes cannot be replaced!) to provide ultimate protection. Team members who are exposed to radiation on a daily basis have a higher incidence of reproductive, thyroid, and eye cancers. Lead aprons, collars, and gloves should never be folded; any fold can crack the lead and allow radiation to penetrate the team member, decreasing safety (Figure 23-9). All apparel should be hung on a wall or laid flat on a table surface to prevent cracking. Aprons, collars, and gloves should be radiographed yearly to check for any cracks that may have appeared (Figure 23-10). Radiographs should be compared year to year, and safety equipment should be replaced as soon as visible cracks appear. Team member safety cannot be compromised. A radiology log can be helpful to team members when a digital system is not used. Figure 17-1 shows an example, listing the date, client and patient name, area being studied, position, and machine settings. This type of log allows team members to retrieve settings used in previous radiographs in case repeat or follow-up radiographs are required. To compare radiographs, the same setting should be used on both. Different settings may produce slight differences in quality of images, thereby making comparison difficult. Digital radiographs have setting information stored with the image, allowing exact settings to be used. Radiograph checkout logs should also be implemented when owners take x-rays for second opinions or when films are sent to a specialist. Figure 17-2 shows a log that allows radiographs to be traced if they have not been returned. After clients have received all appropriate education regarding the procedure and the risk of anesthesia, they must sign an anesthetic release. Examples of anesthetic release forms are provided in Chapter 2. It is imperative that the client’s phone number, cell phone, and/or pager be listed in case an emergency occurs and the client must be contacted during the procedure. Clients must be informed of the risks and benefits the pet is subject to before the procedure is performed. Informed consent ensures that the client has been advised, understands the risks, and agrees to the procedures elected. Chapter 4 defines informed consent in more detail. • Bloodwork: The very minimum that should be offered is bloodwork that evaluates the kidney and liver function, as well as red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelet function. Most manufacturers offer preoperative panels that include blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, glucose, total protein, and a complete blood count. Anesthesia is metabolized by the liver and kidneys; it is imperative to know if they are functioning correctly. If a patient is deficient in platelets, it is helpful to know this before surgery; a patient with low platelets could bleed to death. • ECG: An ECG is an excellent indicator of heart disease. An ECG will detect premature ventricular contractions or other abnormalities that may necessitate postponement of surgery. • IV catheter and fluids: If IV fluids are not a requirement of the practice, the owner should be strongly advised to permit them. IV fluids help maintain the patient’s blood pressure while under anesthesia, help support the kidneys, and allow an access port to the vein in case of emergency. If a patient goes into cardiac arrest while under anesthesia, drugs can be administered much faster through an existing line versus placing a catheter in an emergency. • Histopathology: If a patient is having a mass or growth removed, clients should be advised to send the growth to a pathologist to determine the correct pathology. Many cancerous tumors look benign but are not. A pathologist who reviews cytologies as a profession can make an informed diagnosis of masses submitted.

Clinical Assisting

EXAMINATIONS

Taking a History

Restraint

VACCINATIONS AND DISEASES

Common Diseases

Disease

In-House

Laboratory

FELINE

Calici

PCR

FIP

PCR, antibody

FIV

X

ELISA, Western blot

FeLV

X

ELISA, IFA

Panleukopenia

PCR

Pneumonitis, chlamydia

PCR

Herpesvirus

PCR

Rhinotracheitis

Heartworm

X

ELISA

CANINE

Coronavirus

PCR

Distemper

PCR, conjunctival scrape

Adenovirus

PCR

Bordetella infection

PCR

Leptospira infection

PCR, antibody

Lyme disease

X

IFA, ELISA

Parvovirus

X

PCR, fecal antigen

Heartworm

X

ELISA

Herpesvirus

PCR

EQUINE

Herpesvirus

PCR

Equine infectious anemia

AGID, cELISA

Equine influenza virus

PCR

DIAGNOSTICS

Bloodwork

Test

Associated With

AST

Liver

ALT

Liver

Total bili

Liver

Alk phos

Liver

GGT

Liver

Total protein

Protein

Albumin

Protein

Globulin

Protein

A/G ratio

Protein

Cholesterol

Lipids

BUN

Kidney

Creatinine

Kidney

BUN/crea ratio

Kidney

Phosphorus

Mineral

Calcium

Mineral

Glucose

Diabetes

Amylase

Pancreas

Lipase

Pancreas

Sodium

Electrolytes

Phosphorus

Electrolytes

Na/K ratio

Electrolytes

Chloride

Electrolytes

Triglycerides

Lipids

Magnesium

Mineral

WBC

White blood cell count

RBC

Red blood cell count

HGB

Hemoglobin concentration

HCT

Hematocrit

MCV

Mean corpuscular volume

MCH

Mean cell hemoglobin

MCHC

Mean cell hemoglobin concentration

Total T-4

Thyroid

T-4 equil. dialysis

Thyroid

TSH

Thyroid

Bile acids

Liver

Urinalysis

Electrocardiogram

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

Safety

Guidelines

SURGERY

Preanesthetic Documentation

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT What Would You Do/Not Do?

What Would You Do/Not Do? PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT