Chapter 27 CLINICAL AND DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION OF THE MALE REPRODUCTIVE TRACT

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

SCROTUM.

The scrotum in the normal dog should be sparsely covered with hair, feel relatively smooth and soft, have skin that is freely movable over the testes, be nonpainful to the touch, and have a uniform thickness. It should be assessed visually for signs of inflammation, trauma, or swelling by laying the dog comfortably on its side and gently lifting the upper leg. Chronic or severe scrotal inflammation may alter normal thermoregulatory processes, which in turn may alter spermatogenesis and/or spermatozoal storage in the epididymis. Palpation of the scrotum, separate from the testes, may reveal adhesions from previous or current inflammation. The presence of nodules may suggest granuloma or neoplasia development. Squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, and mast cell tumors may involve the scrotum (Jones and Joshua, 1982). Scrotal thickening may result from inflammation, neoplasia, accumulation of fluid (e.g., lymphedema), testicular or epididymal enlargement, or inguinoscrotal hernia.

TESTES.

In the dog, testicular descent is usually complete within 10 to 14 days of birth, and both testes should be readily palpable by 6 to 8 weeks of age. Failure to palpate both testes, especially in dogs older than 16 weeks of age, is supportive of cryptorchidism (see page 961). In younger dogs, however, temporary retraction of the testis into the inguinal canal or lateral to the penis may occur with nervousness or excitement. This should probably not be considered significant as long as the testis descends into the scrotum when the dog is quiet or relaxed.

The testes should be palpated for size, shape, and consistency. The left testis is usually caudal to the right. The size range for the dog testis is approximately 1 to 5 cm in length by 1 to 3 cm in diameter. Difference in breed sizes precludes an all-encompassing statement regarding normal size of the testis. In general, the size of the testes is roughly proportional to body size. Although evaluation of total scrotal width is an objective way to estimate testicular size, weight, and daily sperm production (Olar et al, 1983), such measurements are not usually made. Testicular asymmetry, bilaterally small testes, or symmetrical enlargement should be considered subjective information indicative of possible abnormalities. Potential causes for testicular enlargement include neoplasia, acute infection or inflammation, testicular torsion, and inguinoscrotal hernia. Potential causes for a decrease in testicular size include degeneration, chronic infection or inflammation, hypoplasia, or intersex states.

PENIS AND PREPUCE.

Without an erection, the prepuce completely encloses the normal canine penis. Small quantities of preputial discharge are usually not clinically significant (i.e., mild balanoposthitis). Worrisome discharges include blood or large amounts of pus. “Normal” balanoposthitis is seen as a mild mucopurulent discharge covering the penile mucosa. The penis should be freely movable within the prepuce and easily exposed by pulling the prepuce caudally over the bulbus glandis. The prepuce can usually be retracted over the bulbus glandis. A narrow preputial opening (phimosis) or adhesions between the prepuce and penis should be suspected in a dog in which the penis cannot be fully exposed. The extruded penis should be thoroughly evaluated for the presence of inflammation, trauma, foreign bodies, or masses. Transmissible venereal tumors may be observed near the bulbus glandis and may be identified only following complete extrusion of the penis (Fig. 27-1). The penile mucosa should be pinkish white, smooth, and nonpainful to touch. Inflammation of the penile mucosa may result in lymphoid hyperplasia and the development of papular lesions.

SEMEN EVALUATION

Semen analysis is integral to the evaluation of possible infertility or subfertility and should be performed as part of a routine prebreeding examination. Semen evaluation should be completed before artificial insemination or freezing (see Chapter 32). Culture of the semen is also indicated in dogs with suspected prostatitis, orchitis, or epididymitis (see Chapters 29 and 30). Because live sperm are normally present in the ejaculate, the clinician must carefully handle the semen to prevent death or artifactual changes in cell morphology or motility as a result of mishandling of the sample. Semen should be examined immediately after it is obtained; any delay may increase the number of dead sperm. Dramatic changes in environmental temperature should be avoided. Ideally, all equipment should be kept near 37° C to prevent temperature extremes. Glass slides and collection devices should be warm, clean, and free of alcohol, powder, or excessive lubricant.

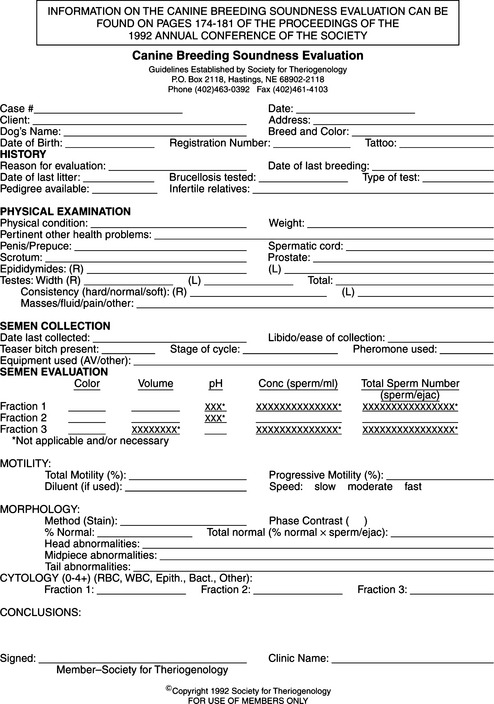

The method of semen collection and the type and sequence of analytic techniques used for semen analysis should be kept consistent. Currently, most of the macroscopic and microscopic evaluation of semen is subjective and usually performed by a qualified technician. Automated sperm analyzer equipment is now commercially available and has become invaluable in the evaluation of semen from human, bovine, equine, and other species. Studies using computer-aided sperm analysis in dogs are beginning to appear in the literature (Smith and England, 2000; Verstegen et al, 2000). Use of techniques allowing objective assessment of spermatozoa function may help identify causes of infertility not previously appreciated (England and Plummer, 1993; Hewitt et al, 2000; Holst et al, 2000), although currently such techniques are not routinely performed. Regardless of the method used to evaluate semen, a standard semen analysis form (Fig. 27-2) should be completed and filed with the patient’s medical records.

FIGURE 27-2 Canine breeding soundness evaluation form distributed by the Society for Theriogenology.

Techniques for Obtaining a Semen Sample

Collection of a semen sample can be accomplished by allowing the male to mount a bitch in heat, by use of a teaser bitch, or by masturbation. Electroejaculation requires general anesthesia and is not commonly used. Latex artificial vaginas (e.g., Canine Artificial Vagina; Synbiotics, San Diego, CA) that funnel semen into a plastic sterile test tube are ideal for collection of semen (Fig. 27-3). Although spermatozoal motility has been reported to be adversely affected by the warm latex lining, we have not recognized this as a clinically relevant problem. Scant amounts of lubricating jelly can be applied just inside the outer rim of the artificial vaginal device, avoiding contact with semen. Excessive lubrication can be deleterious to spermatozoal viability and should be avoided. Plastic (not glass) tubes should be used to prevent breakage of the collection device, which is most likely to occur when the male is exhibiting strong pelvic thrusting. Vinyl rather than latex gloves should be worn to minimize the detrimental effect of latex on spermatozoal motility (Althouse et al, 1991).

FIGURE 27-3 Latex artificial vagina and plastic sterile test tube used for collection of semen in dogs.

TEASER BITCH.

The easiest technique for obtaining a semen sample is to let the male mount a bitch in proestrus or estrus. A teaser bitch in anestrus may also be used, although the sexual interest of the male (thus the results) is less consistent. Application of a topical pheromone preparation (p-hydroxybenzoic acid methyl ester; Eau d’Estrus, Synbiotics, Malvern, PA) to the vulva and hindquarters of a bitch in anestrus to simulate estrus may help (Keenan, 1998). Unfortunately, we have only occasionally observed improvement in stimulating sexual excitement in the male when using pheromone preparations. Alternatively, vaginal secretions from a bitch in estrus can be collected on gauze pads or swabs, stored frozen, and when needed, thawed and held near or applied to the vulva of the teaser bitch for the dog to smell (Keenan, 1998; Freshman, 2001). Both the stud dog and the bitch should be kept on leashes and the bitch restrained to allow the male access to the rear quarters and vulva. The bitch may need to be muzzled (especially if she is not in standing heat) to prevent biting of the holder, collector, or male dog. If the collector is right-handed, he or she should be on the left side of the male dog, with the collection device in the left hand and the dog’s prepuce/penis near the right. The dog is then lead up to the rear quarters of the bitch by an assistant. If the male is inexperienced, a period of foreplay and tentative mounting attempts should be allowed. The collector should gently massage the penis through the prepuce as the dog sniffs and licks the perineal region of the bitch. As sexual excitement increases in the male, he attempts mounting, pelvic thrusts begin, and the penis and bulbus glandis enlarge, all at about the same time. The collector must slide the prepuce back over the bulbus glandis before it becomes fully engorged. This must be done early during the erection process, or enlargement of the bulbus glandis exceeds the preputial opening and the handler is not able to exteriorize the penis and bulbus glandis. If full erection occurs before the bulbus glandis is exteriorized, the dog may experience discomfort or pain and lose the erection before ejaculation occurs or have an incomplete ejaculation. The collector should deviate the penis into the collection device as the male attempts to thrust the penis into the vulva. If an artificial vagina is used, it should be passed over the bulbus glandis and gentle digital pressure applied to the entire circumference of the penis just proximal to the bulbus glandis to maintain the erection. Rapid pelvic thrusting and ejaculation commence almost immediately. Care must be taken to prevent damage to the penis from forcing it too far into the artificial vagina. In addition, as ejaculation commences, the artificial vagina should be gradually withdrawn from the bulbus glandis (unless a soft distensible cone is used) to prevent trauma as the bulbus glandis continues to enlarge.

The first two ejaculate fractions (presperm, 5 to 20 seconds duration; sperm-rich, 30 seconds to 4 minutes duration) are ejaculated during and immediately following the pelvic thrusting phase of copulation, respectively. Once these fractions have been ejaculated, the dog usually dismounts and steps over the bitch and collector’s arm with the hind leg so that the penis is rotated 180 degrees and directed caudally. Most dogs ejaculate prostatic fluid in spurts for several minutes, the volume ejaculated being dependent on the duration of the “tie.” During manual collection, the application of constant pressure around the circumference of the penis proximal to the bulbus glandis maintains the erection and allows collection of prostatic fluid. The transition from a cloudy to a clear ejaculate indicates a transition from the sperm-rich fluid to prostatic fluid (Fig. 27-4). The collection device can be changed shortly after this transition from cloudy to clear fluid if only prostatic fluid is desired for culture and cytologic evaluation.

Macroscopic Evaluation of Semen

VOLUME.

The volume of semen collected is highly variable and depends on the dog’s age, size, frequency of service, and the amount of prostatic fluid collected. Normal volume may range from 1 to 40 ml per ejaculate. It is important to collect all of the sperm-rich (second) fraction when evaluating a dog’s semen. The volume of this fraction varies between 0.5 and 12 ml and is cloudy. The third fraction (i.e., prostatic fluid) is translucent (Fig. 27-4). Once the ejaculate changes in appearance from cloudy to clear, the collector can assume that all of the second fraction has been obtained and the collection procedure can be discontinued. This usually occurs within 5 minutes following discontinuation of the pelvic thrusts. Volume does not correlate with fertility unless the animal fails to ejaculate.

pH.

The normal pH of canine semen ranges from 6.3 to 6.7 and depends, in part, on the amount of prostatic fluid collected. Prostatic fluid has a pH range of 6.0 to 7.4, with a normal mean of 6.8 (Nett and Olson, 1983). The alkaline nature of prostatic fluid is believed to increase sperm motility and help neutralize the acid environment in the vaginal vault during copulation (Jones and Joshua, 1982). An increase in the pH of semen is associated with incomplete ejaculation or inflammation of the testis, epididymis, or prostate gland.

Microscopic Evaluation of Semen

MOTILITY.

Motility of individual spermatozoa should be assessed as quickly as possible after obtaining a semen sample. A drop of semen should be placed on a clean slide and microscopically examined at ×200 to ×400 for progressive forward motion of individual spermatozoa and presence of sperm agglutination. Canine spermatozoa are resistant to cold shock, so the slide need not be warmed (Johnston et al, 2001). Percentage of progressive spermatozoal motility has been demonstrated to decline less quickly in samples held at room temperature than in those held at body temperature. Motility will decline as the light from the microscope heats the drop of semen. Evaluation of spermatozoa under lower powers of magnification may give the false impression of forward motility, when in fact, abnormal side-to-side motion without forward motility is present. Evaluation of progressive forward motility may be difficult in heavily concentrated samples. Highly concentrated samples can be diluted with autologous prostatic fluid, phosphate-buffered saline, 2.9% sodium citrate solution, or a semen extender (Johnston et al, 2001).

Spermatozoal motility is assessed subjectively by visual appraisal; the percentage of motile sperm and the character of motility are evaluated. Progressive forward motility is considered normal movement for spermatozoa and is thought to reflect viability and ability to fertilize the ovum. A normal semen sample should have greater than 70% of the spermatozoa exhibiting vigorous forward motility. Individual spermatozoa should be carefully assessed for type of movement. Spermatozoa that are moving in small circles or that have side-to-side motion without forward progression are not normal. The percentage of actively motile spermatozoa may be altered by exposure of the semen to extremes in temperature, acidic diluents, water, urine, pus, blood, or lubricants. The first ejaculate from a dog following a prolonged period of sexual rest may contain a greater percentage of old and dead sperm that have been stored in the epididymis. This results in a decreased percentage of actively motile sperm. Semen samples obtained on subsequent days should be more normal. Rarely, hypomotile or nonmotile viable spermatozoa may also be seen with Kartagener’s syndrome, an immotile cilia syndrome with an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance. In the dog, this syndrome is characterized by respiratory tract disease, male sterility, situs inversus, deafness, and hydrocephalus (Edwards et al, 1986).

A second semen sample should be evaluated whenever a large percentage of spermatozoa are immotile or dead. Special attention should be directed at collection and sample handling techniques to minimize or eliminate collection artifacts. Latex gloves may have a detrimental effect on spermatozoal motility (Althouse et al, 1991) and should be avoided when collecting a semen sample. Vinyl gloves have a minimal effect on motility. Persistent problems with sperm motility may reflect a problem in the testes, epididymides, or prostate gland (see page 999).

CONCENTRATION.

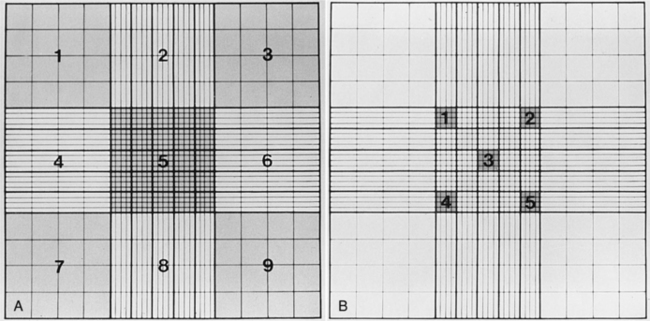

The concentration or number of spermatozoa per ejaculate should be determined by multiplying the number of spermatozoa per milliliter of semen by the total volume (in milliliters) of semen collected. The total volume of semen depends, in part, on the volume of clear prostatic fluid (third ejaculate fraction) collected, thus becoming extremely variable. Evaluation of sperm concentration per milliliter is inaccurate and should not be done. Sperm can be counted using a calibrated spectrophotometer, Coulter counter, or hemacytometer. Use of the 1/100 Unopette (Becton-Dickinson and Co, Rutherford, NJ) white blood cell diluter kit and Neubauer hemacytometer is a relatively quick and inexpensive means of determining sperm concentration. The ejaculate should be mixed gently and the 20-μl Unopette capillary pipette filled with semen and dispensed into the reservoir chamber, which contains 2 ml of diluent. Diluted semen is then dispensed into both chambers of the Neubauer hemacytometer and the number of spermatozoa in the central square (Fig. 27-5) of the nine primary squares is counted on each side of the hemacytometer and the numbers averaged. The number of spermatozoa in the central square is the concentration, expressed in million spermatozoa per milliliter of semen. This value is then multiplied by the volume of the ejaculate to give the total number of sperm per ejaculate. The total number of spermatozoa in the ejaculate of a normal adult dog ranges from 200 million to greater than a billion. The number of spermatozoa per ejaculate varies, depending in part on age, testicular weight, sexual activity, and perhaps, season of the year (see page 939). Larger breeds of dogs also have a higher number of total spermatozoa in the ejaculate than do smaller breeds (Amann, 1986).

MORPHOLOGY.

Smears of the undiluted ejaculate are examined microscopically for structural abnormalities of the spermatozoa. A small drop of fresh, undiluted semen can be placed on a slide and covered with a large coverslip. This spreads the fluid out into a thin film, allowing accurate evaluation of individual sperm without stains. This evaluation is best performed using phase contrast microscopy. Alternatively, semen can be smeared evenly on a glass slide in a manner similar to that of blood; the smear is then air-dried, fixed, and stained. Several stains are available. The rapid three-step Giemsa-Wright stain technique (e.g., Harleco Hemacolor, EM Diagnostic Systems, Gibbstown, NJ; Diff Quik, VWR International, West Chester, PA; Camco Stain Pack, Cambridge Diagnostic Products, Fort Lauderdale, FL) is quick, effective, and readily available in most practices. These stains do not stain the acrosomal area of sperm. India ink and eosin-nigrosin (e.g., Morphology stain, Society of Theriogenology, Lane Manufacturing, Denver, CO; Hancock, Lane Manufacturing, Denver, CO) are background stains that outline the sperm rather than stain the sperm directly. For the latter, a drop of eosin-nigrosin stain and a drop of semen are gently mixed on a warmed microscope slide before being smeared and allowed to air-dry. Spermac stain (Fertility Technologies Inc, Natick, MA) is a rapid stain that offers unique differential qualities. The sperm nucleus stains red; the acrosome, midpiece, and tail stain green; and the equatorial region of the acrosome stains pale green (Oettlé, 1995). Spermac stain can be used on extended semen, since constituents such as egg yolk, serum, and milk commonly included in extenders do not interfere with the staining. Leukocytes do not stain differentially with Spermac stain. Root Kustritz et al (1998) found the percentage of morphologically normal spermatozoa and the percentage of morphologic abnormalities differed depending on the staining technique, suggesting that staining or preparation technique may alter the morphology of canine spermatozoa artifactually. Results of this study emphasize the importance of consistency of preparation and staining technique when comparing sperm morphology within and between dogs.

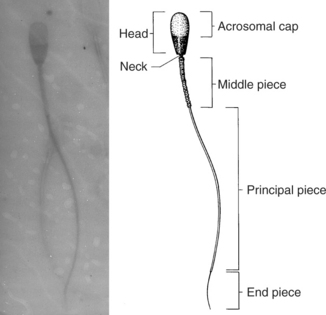

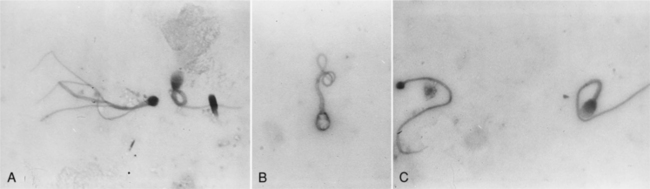

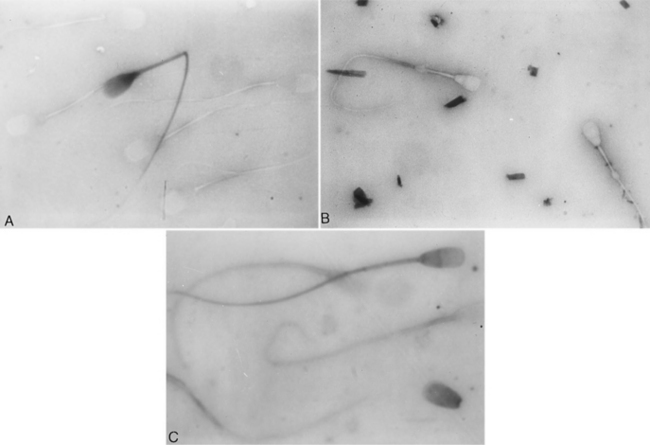

Evaluation of sperm morphology should be completed microscopically using oil immersion. The normal spermatozoa consists of the acrosomal cap, head, neck, middle piece, and tail (Fig. 27-6). The acrosome is a caplike structure covering slightly more than the anterior half of the head, and the middle piece is approximately 1.5 times the length of the head in normal spermatozoa. Individual spermatozoa should be evaluated for abnormalities arising in the head, middle piece, and tail (Fig. 27-6). Commonly identified abnormalities include detached heads, knobbed acrosomes, detached acrosomes, proximal and distal cytoplasmic droplets, reflex (i.e., bent) midpiece, bent tails, tails tightly coiled over the midpiece, and proximally coiled tails (Root Kustritz et al, 1998). Abnormalities may be further classified into primary and secondary abnormalities (Table 27-1; Figs. 27-7 and 27-8). Primary abnormalities are believed to represent abnormalities in spermatogenesis (i.e., within the testes), whereas secondary abnormalities are nonspecific and may arise during transit through the duct system (i.e., within the epididymis), during handling of the semen or following infection, trauma, or fever (Johnston, 1991). A minimum of 200 spermatozoa should be counted and classified; only free heads should be counted, not free tails. The reader is referred to Oettlé (1995) for more information on classification of sperm abnormalities in the dog.

TABLE 27-1 PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SPERMATOZOAL DEFECTS IN THE DOG

Historically, it has been suggested that normal males generally should have greater than 70% morphologically normal spermatozoa and that primary and secondary abnormalities should constitute less than 10% and 20% of the defective sperm, respectively. Positive correlations between percentage of morphologically normal spermatozoa and fertility rate and total number of morphologically normal spermatozoa and pregnancy rate have been demonstrated in the dog (Oettlé, 1993; Mickelsen et al, 1993). Oettlé (1993) found that fertility of dogs was statistically reduced when the percentage of morphologically normal sperm fell below 60%. Using 60% normal sperm morphology as the cutoff point between normal and subnormal, fertility was 61% in a group of 23 normal dogs, compared with 13% in a group of 15 subnormal dogs. Mickelsen et al (1993) found that total numbers of morphologically normal and progressively motile spermatozoa per ejaculate was more important in predicting fertility. Artificial insemination with greater than 250 × 106 morphologically normal sperm resulted in a pregnancy rate of approximately 82% in 27 bitches evaluated. Obviously, total sperm per ejaculate and health of the spermatozoa (i.e., morphology, motility) are all critical in the assessment of fertility of the dog.

Although abnormal sperm morphology is associated with infertility in dogs, there are few descriptions of the effect of specific morphologic defects on fertility. Specific morphologic defects associated with infertility in the dog include abnormalities of midpiece attachment or ultrastructure, microcephalic spermatozoa, and proximal retained cytoplasmic droplets (Johnston et al, 2001).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree