Andrew H. Parks, Stephen E. O’Grady

Chronic Laminitis

Chronic laminitis is defined by mechanical collapse of the lamellae and displacement of the distal phalanx within the hoof capsule. It can occur as a direct sequel to acute laminitis, that is, within the first 72 hours of onset of clinical signs, or as a sequel to subacute laminitis, which is defined as the phase following the acute disease but without mechanical collapse of the lamellae. In simplistic terms, the acute phase is the phase of injury, and the subacute and chronic phases are phases of tissue repair. The chronologic divide between acute and subacute laminitis is obviously arbitrary, because the disease process is a continuum in which the injurious processes gradually yield to restorative processes. The fundamental difference between the pathogenesis of subacute laminitis and that of chronic laminitis is the difference in the repair processes caused by displacement of the distal phalanx. This inevitably has consequences for treatment and prognosis.

Pathophysiology of Chronic Laminitis

Mechanism

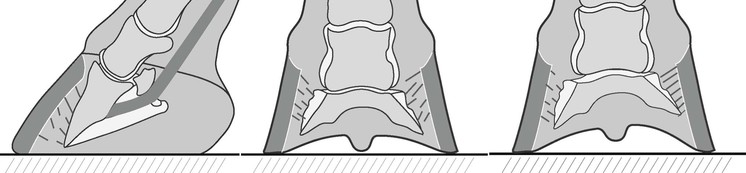

Separation of the lamellae is a consequence of the severity of the original pathologic processes in the face of the mechanical stresses superimposed on the lamellae. Displacement occurs when the load applied exceeds the strength of the lamellae supporting the distal phalanx within the hoof capsule. Three recognized variants of displacement of the distal phalanx have been described (Figure 201-1). The exact reasons for these different patterns are unknown, but it would appear reasonable to assume that the sites of displacement are subject to the greatest stress, the most lamellar injury, or a combination of the two. Clinical observation suggests that conformation is one factor to be considered; horses in which the foot is offset from the axis of the limb, usually laterally, should have greater stress on the side of the foot that is most in line with the metacarpus and displacement on that side of the foot is more likely. When lamellar breakdown occurs dorsally, the resultant rotation of the distal phalanx about the distal interphalangeal joint is such that the angle of the distal phalanx changes in relation to both the ground and the dorsal hoof capsule; this is routinely referred to as rotation, but in this text is referred to as dorsal rotation to differentiate it from other forms of displacement. Capsular rotation refers to deviation of the parietal surface of the distal phalanx with regard to the hoof capsule. Phalangeal rotation refers to rotation of the distal phalanx with respect to the axis of the proximal phalanges (i.e., distal interphalangeal joint flexion). In an acutely rotated horse, both these types of rotation occur simultaneously. When the structural breakdown occurs evenly around the hoof capsule, the distal phalanx displaces symmetrically within the hoof capsule, referred to here as symmetrical distal displacement, but often called “sinking.” When one quarter is affected more than the other, the distal phalanx displaces distally unilaterally, a less frequent scenario than dorsal capsular rotation; here it is referred to as asymmetrical distal displacement, but is sometimes referred to as “unilateral rotation” or “medial/lateral sinking.” In reality it is unlikely that lamellar injury is confined to any one area around the perimeter of the foot, so most horses display a combination effect.

Immediately following mechanical failure of the dorsal lamellae and rotation of the distal phalanx, the dorsal hoof wall is still straight and of normal thickness, and the space created by the separation is filled with hemorrhage and inflamed and necrotic tissue. The result of the repair process is that the space is variably filled with hyperplastic and hyperkeratinized epidermis, commonly referred to as the lamellar wedge. The lamellae exhibit varying degrees of dysplasia, widening, fusion, shortening, or loss of primary or secondary lamellae. This results in a loss of contact surface area between the epidermal and dermal lamellae and consequent decreased strength of attachment. Furthermore, displacement of the distal phalanx can result in elongation of the coronary dermis at the expense of the lamellar dermis, further weakening the strength of the attachment of the wall to the distal phalanx. Displacement of the distal phalanx also causes the solar dermis to be displaced dorsal to the margin of the distal phalanx, which causes disorientation of the corresponding sole growth, including growth of horn in toward the distal parietal surface of the distal phalanx. The combination of this disoriented dorsal solar hoof growth and the lamellar wedge results in an increased width of the white line. The displacement of the distal phalanx causes the sole to move distally. The combination of the decreased structural integrity of the attachment of the distal phalanx to the hoof wall and disruption of the sole wall junction increases the percentage of the weight borne by the sole that is directly transferred to the distal phalanx. This change in weight transmission in conjunction with the dropped sole causes trauma to the tissues between the sole and distal phalanx.

Concurrent with lamellar repair is continued hoof growth and development of the characteristic distortion of the dorsal wall. The severity of the distortion of the hoof wall varies with changes in thickness and divergence from the parietal surface of the distal phalanx. The change in thickness of the hoof wall appears to be related to a change in the conformation of the coronary groove so that it is wider and shallower. There are several potential causes for the redirection of the dorsal hoof wall away from the distal phalanx: the differential growth rate between the hoof at the heels and toe, the composition of the repair tissue between the hoof capsule and the distal phalanx, pressure on the distal surface of the wall causing continued distraction from the distal phalanx, and redirection of the dermal papillae at the coronary band and at the sole wall junction.

At the onset of chronic laminitis, the eventual degree of hoof capsule distortion is unpredictable. In most horses, new wall growth that advances from the coronary band is approximately parallel to the parietal surface of the distal phalanx, at least until it has reached the junction of the proximal and middle thirds of the hoof wall. At this juncture the proximal and distal portions of the hoof wall form two distinct angles with the ground that are separated at the margin between hoof wall formed before the onset of laminitis and that formed subsequently. As the new hoof wall grows through the middle third of the dorsal hoof wall, a varying degree of deviation away from the parietal surface of the distal phalanx occurs. In other horses the newly formed hoof wall diverges from the parietal surface of the distal phalanx at the coronary band.

Forces Associated With Chronic Laminitis

The greatest stress imposed on the lamellae is weight bearing. The distribution of weight across the ground surface of the foot is considered important in both the type and magnitude of displacement of the distal phalanx that occurs and in the management of displacement. The magnitude of the forces on the foot is usually discussed in terms of the ground reaction force, that is, the force that is exerted by the ground that opposes the force exerted by the limb on the ground. The ground reaction force is said to act at the center of pressure. At rest the ground reaction force is approximately 30% of a horse’s weight for each forelimb and 20% for each hind limb, and the center of pressure is approximately in the center of the foot. As the horse moves, the magnitude and position of the ground reaction force change so that at breakover there is an increase in the force applied to the dorsal aspect of the hoof capsule.

Complications

Complications during rehabilitation from chronic laminitis are common and include infection, perforation of the sole, distortion or contraction of the hoof, and contracture of the flexor apparatus. The combination of a cavity filled with hemorrhage or necrotic tissue and damage to the structural integrity of the sole wall junction is an invitation to infection. Most frequently the infection involves the nonkeratinized layers of the epidermis and the dermis. The resulting accumulation of exudate causes pain and further separation of the hoof capsule from the underlying soft tissues. Drainage may occur at the coronary band, through the white line, or through the sole, and separation of the hoof capsule may become extensive. If the wall is sufficiently unstable, movement of the wall of the hoof capsule against the underlying soft tissues may cause severe chafing and loss of germinal epithelium. If sufficient damage occurs, infection spreads to the distal phalanx. Contraction of the hoof capsule may be secondary to the pain and limited weight bearing or may result from certain shoeing practices used in the treatment of the disease, namely inappropriate placement of the nails in the foot and elevating the heels. Contraction of the flexor tendon apparatus is also likely a sequel to chronic pain.

The exact causes of pain in chronically laminitic horses are undetermined but are likely to be related to continued ischemia, inflammation, and trauma to the dorsal lamellae and ischemia or inflammation associated with bruising of the soft tissues of the sole immediately distal to the solar margin of the distal phalanx. There may also be a neuropathic basis for a component of laminitic pain. Additionally, pain may be associated with a focus of infection causing increased subsolar or intramural pressure (see Chapter 14 for more information on pain control in laminitis).

Presentation, Diagnosis, and Evaluation

The diagnosis of chronic laminitis is seldom a challenge because the gait and appearance of the foot are characteristic of the disease, and radiographs usually remove all doubt. Occasionally, nerve blocks are necessary to localize the pain to the foot in mildly affected horses and should be interpreted in conjunction with the results of hoof tester application and radiographic findings.

Horses with chronic laminitis have several possible clinical manifestations: (1) as the continuation of acute laminitis, (2) as a recurrence of past chronic laminitis, or (3) with an unknown history because the acute phase was never observed or the horse was purchased without knowledge of the disease.

Full evaluation of the history, examination of the entire horse, and examination of the digits are all important in determining the prognosis and treatment. The severity of the initial acute phase is the best indicator of the extent of the original damage and constitutes a major factor in the prognosis. The duration of the disease since the onset of the acute phase gives some indication as to how much the lamellar repair process may have destabilized the distal phalanx within the hoof capsule. In horses with chronic laminitis, the degree of lameness (manifested by willingness of the horse to walk, how stilted it walks, how willing it is to lift a foot, and how much it lies down) does not always correlate with the prognosis as well as it does with the prognosis in acute laminitis, and does not necessarily correlate with the clinical appearance of the foot or the radiographic changes. How the animal preferentially places its foot may indicate the distribution of lamellar injury; for example, a horse that preferentially bears weight on its heels reduces the tension in the dorsal lamellae and the compression of the sole beneath the dorsal margin of the distal phalanx. Similarly, a horse that is landing on one side of the foot may be protecting the contralateral wall or sole, although this asymmetrical landing may also be caused by conformation. The digital pulse should always be evaluated for intensity. Evaluation of the coronet, hoof wall, sole, and white line, combined with the response to hoof tester examination and palpation of the coronary band, provides clinical indicators of the pathology that has occurred within the hoof. This pathology may include capsular distortion, displacement of the distal phalanx, infection, and secondary contraction of the hoof or flexor apparatus.

Radiology

The radiographic features of chronic laminitis have been well documented. High-quality lateral, dorsopalmar, and dorsopalmar oblique projections are necessary. The exposure must include good images of the hoof capsule. A radiopaque marker is invaluable in determining the position of the distal phalanx in relation to the dorsal surface of the hoof capsule on the lateral radiograph; it should be placed on the midsagittal dorsal hoof wall, starting at the coronary band and extending distally. Additionally, for the dorsopalmar radiograph, linear markers may be placed on the medial and lateral walls of the hoof capsule. Additionally, to ensure the maximal information is obtained from the radiographs, they should be obtained with the horse standing on a flat level surface and bearing weight evenly and with the metacarpal bone vertical to the ground. The horse should be standing on two wooden blocks of equal height that have embedded radiodense markers to indicate the plane of the ground surface.

The lateral radiographic view should be examined to determine the thickness of the dorsal hoof wall, the degree of capsular rotation, the angle between the solar margin of the distal phalanx and the ground, the distance between the coronet and the proximal margin of the extensor process, and the distance between the dorsal margin of the distal phalanx and the ground. The dorsopalmar view is most useful for determining whether there is asymmetric distal displacement of the distal phalanx within the hoof capsule; specifically, asymmetric displacement is associated with a decrease in the distance from the distal phalanx to the ground, an increase in the distal interphalangeal joint space, and increased wall thickness on the affected side. The location of gas pockets is determined by correlating the findings of the lateral and dorsopalmar views. The margin of the distal phalanx is evaluated for pedal osteitis, sequestra, and marginal fractures on the oblique dorsopalmar view.

Positive-contrast venography of the foot may indicate filling defects in the digital vasculature that signify a poor prognosis—namely, defects in filling of the lamellar vessels, the circumflex area, and the terminal arch. It is important that the venogram is performed with appropriate technique, including application of an effective tourniquet and infusion of the contrast medium while the foot is unloaded to prevent artifactual filling defects. The venogram, when used, should always be performed and interpreted by a clinician that has experience in use of this modality.

Outcome and Prognosis

The eventual outcome of treatment for horses with chronic laminitis can be divided into functional and morphologic outcomes. The functional outcome is most likely to dictate whether the horse can return to athletic activities, can regain only pasture soundness, or must be euthanized. The morphologic outcome is more likely to determine the degree to which continued and potentially lifelong therapeutic measures will be necessary. Although there is fair correlation between the functional and morphologic outcomes, some horses with seemingly modest morphologic changes are euthanized, whereas others are performing more strenuous athletic activity than the morphologic appearance would lead one to expect.

At the onset of chronic laminitis, the eventual outcome is hard to predict, but the most important indicator for survival remains the severity of the initial insult to the lamellae. The appearance of the initial radiographs does not necessarily correlate with either the functional or the morphologic outcome. However, the thickness of the sole and the angle between the solar surface of the distal phalanx and the ground are fair indicators of the difficulty of treatment of horses with dorsal phalangeal rotation, and both are more useful than the degree of capsular rotation in successfully predicting the rehabilitation of the horse. The thickness of the soft tissues dorsal to the parietal surface of the distal phalanx and the distance between the coronet and extensor process are suggestive of the prognosis in horses with distal displacement of the distal phalanx because these indicate the severity of the original injury. In horses with capsular rotation, the eventual morphologic outcome only becomes apparent as the new dorsal hoof grows down through the middle third of the wall.

Treatment

The desired outcomes of treatment of horses with chronic laminitis are freedom from pain and feet with normal appearance and function. Obviously there are major limitations that interfere with achieving these ideals. The treatment of chronic laminitis is multifaceted and includes providing supportive care of the feet, medical therapy, surgical intervention, and nutritional management. In contrast to treating horses with acute laminitis, in which medical therapy frequently assumes priority, supportive therapy or therapeutic farriery is the most important element for success in treating horses with chronic laminitis.

Supportive Therapy

It is not possible to directly reattach mechanically separated lamellae. Rather, the return of mechanical function of the wall is a gradual process that may take as long as 9 months, barring complications. Supportive therapy maintains an environment that enhances natural healing; in horses with chronic laminitis, this means rest and farrier care. Absolute stall rest in the acute and early stages of chronic laminitis is imperative because movement increases stress in the damaged lamellae. Later on, rest should be balanced against the need to restore normal function of the hoof capsule, which comes with repeated expansion and contraction as the animal moves and loads the foot.

The mainstay of hoof care is therapeutic shoeing. In considering hoof care in horses with chronic laminitis, there are three goals of therapy: to stabilize the distal phalanx within the hoof capsule, control pain, and encourage new hoof growth that will assume the most normal relationship possible with the distal phalanx. It is necessary to stabilize the foot to limit further injury to the remaining lamellar attachments or to the new lamellar attachments being formed. It is desirable to control the horse’s pain for humane reasons as well as to restore some degree of function to spare the other limbs from excessive weight bearing. Encouraging the foot to return to normal form, both in appearance and anatomically, is the surest way to optimize future function.

Attempting to stabilize the distal phalanx within the hoof capsule is important in preventing further rotation or displacement of the distal phalanx, promoting healing, and decreasing pain. Therefore, understanding how the stability of the distal phalanx within the hoof capsule affects the convalescence of a chronically laminitic horse is crucial to effective treatment. Unfortunately, there is no direct measure of phalangeal stability except the obvious progression of displacement as determined by radiographs and the horse’s pain level. It is assumed that the distal phalanx is least stable immediately after displacement and that it becomes more stable with time as the tissues repair unless there is another acute episode of the disease. The best indication available that the distal phalanx is more stable is that the horse is more comfortable because increased stability decreases tissue trauma. It is important to differentiate between the temporary stability that can be produced by supportive hoof care and the more permanent type of stability obtained with tissue repair; the former is immediately reversed if the supportive care is discontinued.

To achieve each of these goals, several principles or objectives must be followed. These objectives, which include redistributing the load on the foot, addressing breakover, and providing heel elevation, cannot be completely separated from the goals because the goals are at least in part interdependent. For example, increasing stability helps decrease pain because instability is in part the cause of pain. Although instability and pain in the foot are both of immediate concern when treating chronic laminitis, restoring the normal relationship between the distal phalanx and the hoof capsule is initially a secondary consideration; the latter becomes more important as instability and pain are controlled and the new hoof wall begins to grows out.

Stabilizing the hoof capsule requires decreasing the stress on the most damaged lamellae. Therefore the objectives are to reduce the load on the most severely affected wall, transfer load to the less severely affected wall, and decrease the moment about the distal interphalangeal joint as necessary. Pain caused by lamellar stress and injury is in part controlled by increasing stability within the foot. Pain associated with subsolar ischemia, trauma, and bruising is limited by shoeing to prevent direct pressure on the ground surface of the foot immediately distal to the margin of the distal phalanx. The most important principle in limiting the residual capsular rotation as the hoof initially grows out is to eliminate load on the distal dorsal hoof wall. At a later stage, if there is concavity to the dorsal hoof wall, more direct intervention may be needed. A limited, though steadily increasing, number of tools are available to the veterinarian and farrier to apply these principles, but the permutations in which the principles may be applied is far greater.

The starting point of supportive therapy varies greatly with clinical severity, pattern of distal phalangeal displacement, and prior duration of the disease. As such, each horse must be treated as an individual. Therefore no one technique applied systematically in the same manner is going to be satisfactory for all cases. Above all, focus should be maintained on principles rather than the battery of farriery techniques or methods that are available.

The three different types of distal phalangeal displacement warrant separate discussion. The variations in clinical severity and duration of disease are infinite, and it is not possible to cover all scenarios in this chapter. Therefore the chapter describes treatment for the most severely affected on the understanding that more mildly affected horses may not need all of the measures applied. For example, a horse severely affected with dorsal distal phalanx rotation may need modification of breakover, recruitment of weight bearing by the sole and frog, and heel elevation, whereas a less severely affected horse may need only an improvement in breakover with or without increased weight bearing by the sole and frog.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree