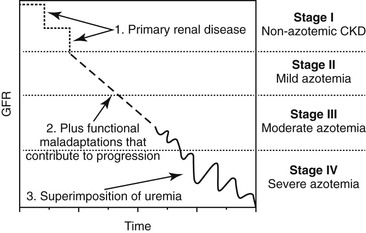

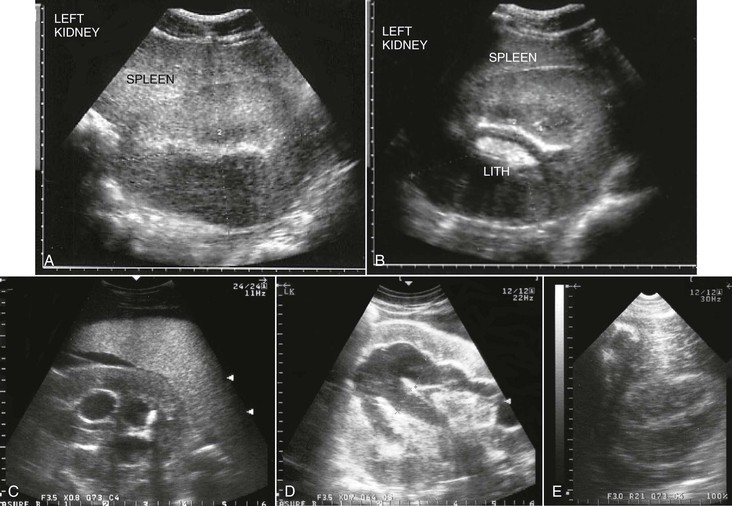

Harold C. Schott II, During the past decade, a change in terminology has been adopted in human and small animal medicine for individuals with chronic renal disease. Rather than describing patients as having chronic renal failure (CRF, often an end-stage problem), the term chronic kidney disease (CKD) has been introduced to shift attention to detection of earlier stages of renal disease. The International Renal Interest Society has developed a staging system for CKD in dogs and cats based on serum creatinine concentration (Figure 111-1), and it is logical that similar stages occur in equids with CKD. Although CKD is by nature a progressive disorder, early detection and intervention may slow the rate of progression. Two major complications accompany CKD in small animal patients: hypertension and proteinuria. When these complications are controlled with diet and medication, the rate of progression of CKD can be slowed. Although not commonly assessed, hypertension and proteinuria can also develop in equids, and it is logical that control of these complications would improve long-term management of horses with CKD. Fortunately, end-stage CRF is an uncommon problem in horses. Data retrieved from the Veterinary Medical Database at Purdue University yielded information on 515 of 442,535 horses admitted to participating veterinary teaching hospitals during the years 1964 through 1996 with a diagnosis of CRF (prevalence, 0.12%). However, this value is probably an underestimation because euthanasia was likely performed in a number of horses with chronic weight loss without a definitive diagnosis being established. As in small animals, CRF appears to be a greater problem in older horses: the prevalence increased to 0.23% in horses older than 15 years. A prevalence of 0.51% in intact males older than 15 years could suggest that stallions are at greater risk for developing CRF. However, an alternate explanation for a higher prevalence in older stallions may be that a greater value led to increased likelihood of diagnosis and attempt at management. Causes of CKD in horses can be grouped into anomalies of development, glomerulonephritis, and tubulointerstitial disease termed chronic interstitial nephritis. In a report of 99 horses with CRF, signalment included a number of breeds, but Thoroughbreds (29%), Standardbreds (10%), and Clydesdales (10%) were more commonly affected. Sex distribution was 44% mares, 40% geldings, and 16% stallions. Of interest, one third of all cases occurred in horses that were younger than 6 years, and congenital renal disorders were found in 16% of horses. Approximately one half of the acquired cases were attributed to glomerulonephritis (53%), and the remainder had chronic interstitial nephritis (39%) or end-stage kidney disease (8%). However, this case series was compiled by combining 29 clinical cases examined by the author with 70 previously reported cases. It is likely that glomerulonephritis has been overrepresented in published reports because of interest in characterizing and comparing glomerular lesions with those described in other species. In this author’s experience, primary glomerulonephritis appears to be rare and is likely responsible for development of CKD in less than 10% of affected equids. Congenital disorders include renal agenesis and hypoplasia, renal dysplasia, and polycystic kidney disease. Horses with unilateral renal agenesis or renal hypoplasia are born with less renal functional mass but may never develop clinical evidence of renal insufficiency as long as renal tissue contains 30% to 40% of normal nephron numbers. However, these anomalies increase risk for developing CKD if the horse is challenged by other disorders (e.g., colic or enterocolitis) that can be accompanied by a degree of acute kidney injury (AKI) and the use of potentially nephrotoxic medications that can lead to some loss of functional nephrons. Renal dysplasia is an embryologic disorder in which both glomeruli and tubules fail to develop normally, resulting in glomeruli of variable size and tubules that vary from near-normal structures to blind-ending structures that are nonfunctional. Most cases of renal dysplasia have been reported in horses younger than 1 year, but affected individuals have also survived for several years before CKD has been recognized. Polycystic kidney disease has been reported in a limited number of equids. In humans, dogs, and cats, polycystic kidney disease is usually a genetic disease with both dominant and recessive modes of inheritance. Over the first few months to years of life, cystic structures within the kidneys slowly enlarge, leading to a progressive decline in renal function. In some instances, the kidneys increase dramatically in size, whereas with other forms of the disease, the kidneys are not grossly enlarged but contain multiple, variable-sized cysts (Figure 111-2). Although polycystic kidney disease is uncommon in horses and no familial occurrence has yet been described, it would be logical to consider that there is a genetic basis for this disease in horses. Anomalies of development should be included in the differential list for horses with CKD that are younger than 10 years and for which no risk factors (e.g., prior disorders accompanied by prolonged hypovolemia or sepsis or exposure to nephrotoxins) exist. Glomerular injury leading to focal glomerular disease is a common pathologic lesion in horses, but progression to clinical CKD remains a rare event. In one postmortem study, 16% of 45 horses examined had glomerular lesions on light microscopy and 42% (22 of 53 horses examined) had deposits containing immunoglobulin or complement on immunofluorescent staining. Although these findings suggest that as many as one third of horses have microscopic evidence of renal disease, only one of the horses in this survey had signs of CRF. Use of the term glomerulonephritis is typically reserved to describe renal disease in which immune-mediated glomerular damage is suspected to be the initiating factor in development of CKD. The hallmark of glomerulonephritis is increased permeability of the glomerular barrier, characterized by proteinuria and microscopic (and occasionally macroscopic) hematuria. Light microscopic examination may reveal hypercellularity of the glomerular tufts (proliferative glomerulonephritis) or thickening of the glomerular barrier (membranous glomerulonephritis). Immunohistochemical staining with anti–equine immunoglobulin antibodies may reveal immunofluorescence in either a scattered (lumpy-bumpy) or linear (membranous) pattern, consistent with immune complex deposition within the glomerular basement membrane or autoantibodies attached to glomerular basement membrane antigens, respectively. In horses, chronic infections leading to a prolonged period in which circulating immune complexes could be deposited in the glomerular basement membrane are most likely to result in glomerulonephritis. For example, experimental Leptospira pomona infection produced subacute glomerulonephritis characterized by hypercellularity and edema of glomerular capillaries. Similarly, experimental infection with equine infectious anemia (EIA) virus produced histologic and immunofluorescent evidence of glomerulonephritis in 75% and 87% of infected horses, respectively, and EIA viral antigens were eluted from the glomerular basement membrane. However, clinical renal disease was not observed in any of the experimentally infected horses. Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis is a well-recognized cause of CKD in humans, and Streptococcus equi subsp zooepidemicus and subsp equi are common causes of chronic infection in horses. Immune complexes composed of group C streptococcal antigen and immunoglobulin G have been identified in the glomerular basement membrane of a horse with CRF that had a history of prior respiratory disease from S equi subsp zooepidemicus infection. An occasional case of glomerulonephritis may also be a consequence of autoimmune disease in which autoantibodies are directed against basement membrane antigens. Similarly, immunoreactivity to immunoglobulin M in the glomerular basement membrane was reported in a horse with chronic ill thrift and moderate to severe hypoproteinemia and proteinuria, but no evidence for an inciting infectious agent was found. Finally, subclinical glomerulonephritis likely goes unrecognized in many equine patients with infectious disease. For example, the author has observed hematuria and proteinuria in a few horses with purpura hemorrhagica, but clinical CKD has not developed in these horses.

Chronic Kidney Disease

Evolution of Terminology and Incidence of Chronic Renal Failure

Causes of Chronic Kidney Disease

Anomalies of Development

Glomerulonephritis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree