Stephen M. Reed

Cervical Vertebral Stenotic Myelopathy

Cervical vertebral stenotic myelopathy (CVM) is the most common cause of spinal ataxia in horses and has a worldwide distribution. The condition is characterized by ataxia involving all four limbs. The condition can be recognized in horses at a very young age (<6 months) but can also be identified in horses older than 5 years. When the condition is recognized in young horses, a conservative program focused on diet and exercise to carefully regulate the rate of growth can be used. Alternatively, surgical correction with a ventral stabilization procedure can be performed at any age.

Clinical Signs

Diagnosis of cervical vertebral stenotic myelopathy begins with neurologic examination, by which the examiner identifies the affected neuroanatomic site in the cervical portion of the spinal cord. The examination primarily involves careful assessment of the horse’s gait, because reflex testing and postural reactions are difficult and sometimes dangerous to perform in large animals. Clinical signs in horses with CVM often include symmetric ataxia, paresis, and spasticity involving all four limbs but most prominent in the pelvic limbs. Signs are a result of damage to upper motor neuron and general proprioceptive tracts in the spinal cord. Descending upper motor neuron tracts help regulate muscle tone and support of the body against gravity as well as initiation of movement, and damage to these tracts results in a spastic gait. Damage to the ascending proprioceptive tracts results in loss of awareness of where the limbs are in space, causing the horse to lose coordination, appear ataxic, and often have an uneven stride length and height.

During the neurologic examination, the horse should be observed walking in a straight line to look for signs of weakness, such as knuckling, stumbling, dropping of the hip during the stride, or dragging the toe. Other abnormalities include variability in stride length, floating of the limbs in the air, and swaying of the limbs or body (i.e., truncal sway). When walking in circles, affected horses often circumduct or have an outward swaying of the pelvic limb on the outside of the circle. Walking the horse with the head elevated often exacerbates all signs and sometimes results in pacing and truncal sway. The tail-pull test can be used to assess pelvic limb strength. The horse’s tail should be pulled while the horse is standing at rest and while walking. Thoracic limb strength can be assessed by pulling on the mane or hopping the horse on its thoracic limbs. Many horses with spinal cord disease have difficulty backing and can only drag the limbs backward slowly.

Clinical signs of CVM can be identified at an early age, in some instances before 3 months of age. When signs are observed in older horses, they are often a result of arthritic changes involving the articular process joints and intervertebral bodies and may be associated with reduced range of motion and pain when the head and neck are manipulated. The onset of clinical signs is acute in many horses, despite the fact that the arthritis may have been present and slowly progressive for several months.

Diagnosis

Neurologic Examination

Following neuroanatomic localization, the most valuable test for diagnosing cervical vertebral malformation is to identify stenosis of the vertebral canal. This begins with evaluation of lateral radiographic views of the cervical vertebral column. In some cases, the vertebral alignment may be so abnormal that subjective examination is sufficient to make the diagnosis of vertebral canal stenosis (Figures 82-1 and 82-2).

Standing Cervical Radiographs

For standing radiography of the neck, the horse should be positioned with the head and neck in a neutral position. The cassette is placed on one side of the horse, and the x-ray tube and beam are centered on the cassette from the opposite side of the horse. This might seem like a simple task but often proves challenging. In the author’s experience, the most common reason for inability to measure intervertebral and intravertebral sagittal ratios is the lack of good radiographic positioning and inability to identify the proper landmarks for measurements. Radiographing recumbent horses may necessitate use of pads and wedges placed under the animal’s neck and head to achieve appropriate positioning, with the cervical part of the spine aligned parallel to the ground. A three- or four-image series is generally adequate to image the entire cervical and proximal thoracic vertebral column through T1 or T2, depending on the size of the horse. Radiographic views should provide some overlap to be certain all seven cervical vertebrae are included and are positioned for proper identification of the anatomic features of each vertebra, for evaluation of size and shape of the articular process joints, and for assessment of vertebral alignment.

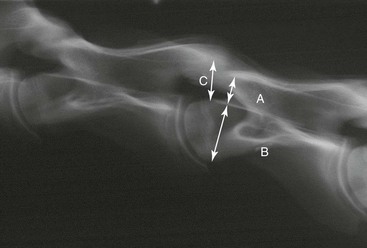

The normal equine vertebral canal in the cervical region should show good vertebral alignment with a gentle curve. Evidence of subluxation or abnormal angulation between adjacent vertebrae may be an indication of malformation or narrowing of the vertebral canal (Figure 82-3). Abnormal changes often identified on the vertebral bodies include enlarged physes with dorsal projection of the caudal vertebral body epiphysis (often referred to as the ski-ramp appearance), osteochondrosis of the articular process joints in young horses, and osteoarthritis in older horses. Elongations of the dorsal laminae into the intervertebral space and above the cranial physis of the next caudal vertebrae are typical changes observed on radiographs of horses with CVM. Identification of these findings is indicative of CVM, but these changes are not adequate to diagnose the exact location of spinal cord compression. A myelogram is required to identify the site or sites of stenosis. Objective measurements of the vertebral canal can be made by use of the sagittal ratio technique (Figure 82-4). The sagittal ratio can be calculated as the ratio of the minimum sagittal diameter of the vertebral foramen to the maximum sagittal diameter of the vertebral body. The measurement of the vertebral body is taken at the cranial aspect of the vertebrae, usually just caudal to the cranial epiphysis and perpendicular to the vertebral canal.

A sagittal ratio (see A/B in Figure 82-4) of less than 50% for C3, C4, and C5, less than 52% for C6, and less than 56% for C7 is indicative of a narrow vertebral canal (Moore et al, 1994). An intervertebral sagittal ratio (C/B in Figure 82-4) of less than 48% at any site in the vertebral canal carries a 100% probability of stenosis (Hahn et al, 2008).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree