Chapter 60Cervical Stenotic Myelopathy

Clinical Signs

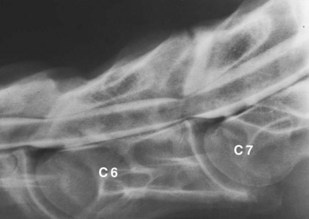

In some instances arthropathy of the caudal cervical vertebral articular processes may produce forelimb lameness, caused by spinal nerve root compression, without producing clinical signs of spinal cord compression.8 Affected horses typically have a short cranial phase of the stride and a low forelimb foot arc and may stand or walk with the head and neck extended (see Chapter 53). Rarely, diskospondylosis of the cervical vertebrae produces a short-strided gait and cervical pain, with or without spinal ataxia (Figure 60-1). Horses with diskospondylosis or arthropathy of the caudal vertebrae may exhibit signs of lameness, pain, or stiffness with the neck in only certain positions or when the head and neck are manipulated or the horse is turned. For example, some affected horses may be unwilling to turn the neck laterally when offered food.

Dynamic spinal cord compression usually occurs in younger horses (<2 years of age) and is associated with instability of the cervical vertebrae, particularly between C3 and C6. Dorsal laminar extension, caudal epiphyseal flare, or abnormal ossification patterns may contribute to the problem. Static vertebral canal stenosis (type II) is characterized by constant spinal cord compression, regardless of neck position (Figure 60-2), and is seen usually in older horses.9 It generally results from osteoarthritis (OA) of the articular processes and proliferation of periarticular soft tissue structures. Synovial cysts, which are often associated with OA of the articular processes, may produce waxing and waning, or acute-onset asymmetrical neurological signs. In some horses with static compression, flexion of the neck stretches the ligamentum flavum and relieves spinal cord compression, whereas extension exacerbates the problem.

Diagnosis

The following neurological disorders should be considered potential differential diagnoses and may produce signs similar to or indistinguishable from CSM: equine protozoal myeloencephalitis (EPM), equine degenerative myeloencephalopathy (EDM), equine herpesvirus–1 (EHV-1) myelitis, occipitoatlantoaxial malformation, spinal cord trauma, vertebral fracture, vertebral abscess or neoplasia, and verminous myelitis (see Chapter 11).

Horses with traumatic cervical vertebral disorders usually exhibit pain during manipulation or palpation of the neck, and the disorder may sometimes be differentiated from CSM by standing radiographic examination. Occipitoatlantoaxial malformation (see Chapter 53) occurs primarily in Arabian horses and is diagnosed definitively by radiological evaluation (see Figure 53-4, B). EDM is diagnosed by exclusion (unremarkable cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] cytological examination findings, negative immunoblot analysis for Sarcocystis neurona, and negative radiological findings and myelographic examination findings). A veterinarian may suspect EDM based on the age (usually less than 18 months) and during neurological examination (hyporeflexia, and similar degrees of ataxia in the forelimbs and hindlimbs), but definitive diagnosis is achieved only by postmortem examination. Although several breeds have been reported with the disease, EDM appears to have a familial predisposition in Standardbred horses.10 Horses with EHV-1 myelitis may have urinary incontinence, poor tail tone, and hindlimb lower motor neuron weakness. Signs associated with cranial nerve involvement may occasionally be observed. In EHV-1 myelitis, CSF evaluation typically reveals xanthochromia and albuminocytological dissociation (high protein concentration, normal cell count); a rising EHV-1 serum antibody titer, virus isolation, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) diagnosis all may be used to provide supportive evidence of EHV-1 myelitis. In areas where EPM is endemic (such as North and South America) or in horses exported from these regions, distinguishing between EPM and CSM can be difficult. Asymmetrical ataxia, focal sweating, and focal muscle atrophy should direct diagnostic efforts toward EPM; however, symmetrical spinal ataxia does not preclude a diagnosis of EPM. EPM-affected horses with symmetrical ataxia are differentiated from those with CSM on the basis of standing radiographic examination, CSF immunoblot analysis for S. neurona,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree