Chapter 10 THE CAT: COMPARATIVE ASPECTS

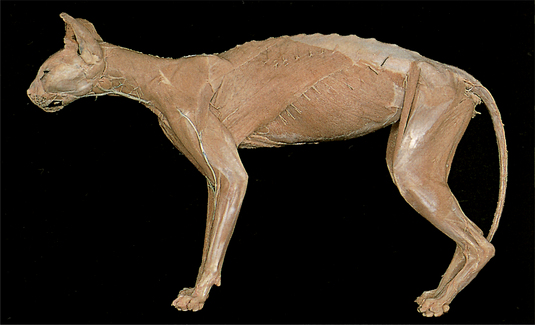

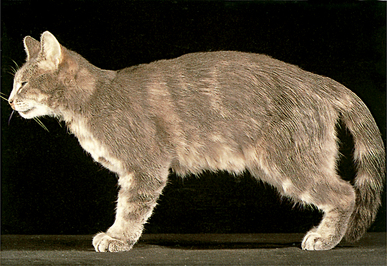

Fig. 10.1 Surface features of the cat: left lateral view. The cat differs from the dog in a number of ways (see Fig. 1.1), although most are differences in shape and proportion. Rather than attempting a comprehensive coverage of gross feline anatomy, which is beyond the scope of this book, the few significant gross anatomical differences are illustrated in this chapter. The most obvious of these differences ascertainable on surface examination are: (i) shortened face with greater development of the vibrissae on the muzzle and an absence of vibrissae from below the chin; (ii) elliptical pupil in the eye which can be almost completely closed up in bright light to a practically vertical slit; (iii) tooth reduction to a purely sectorial dentition with relatively longer and stronger canines designed for stabbing, a considerable post-canine space, and carnassials the most scissor-like of the carnivores; (iv) short, curved and pointed claws which are retractile; (v) short, caudally-directed penis with prepuce opening close to the scrotum.

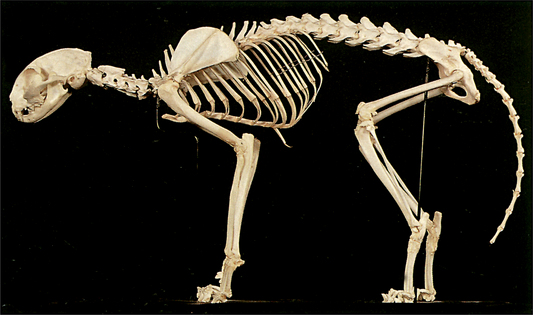

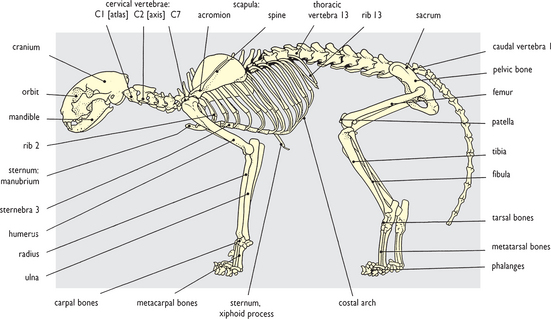

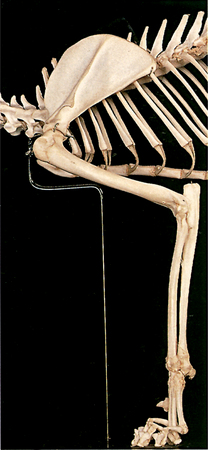

Fig. 10.2 Skeleton of the cat: left lateral view. Skeletal pictures and radiographs are used to demonstrate the osteology of the cat. Of immediate significance is the close overall similarity to the dog, although the bones generally are built to a more delicate plan. A skeletal picture does provide a clear indication of the difference in posture between the two animals (compare with Fig. 1.2).

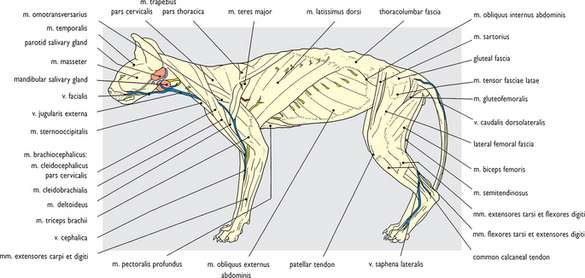

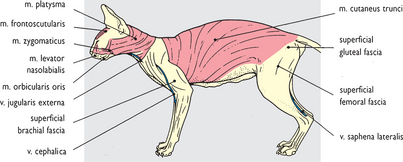

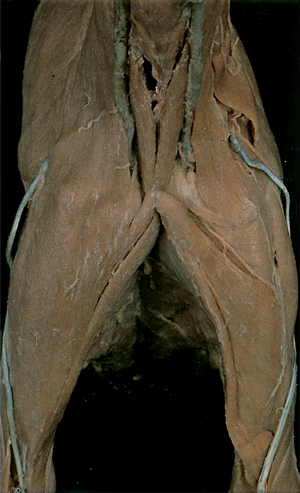

Fig. 10.3 Superficial structures and cutaneous muscles: left lateral view. The skin has been removed revealing the superficial fascia comparable in extent to that in the dog (see Figs 2.24, 3.6, 4.10, 4.50, 5.6, 6.11, 7.11, 7.42, 9.9 and 9.10). The cutaneous muscle of the trunk is greater in extent in the cat, clearly originating from the rump and sacral region and possibly from the base of the tail.

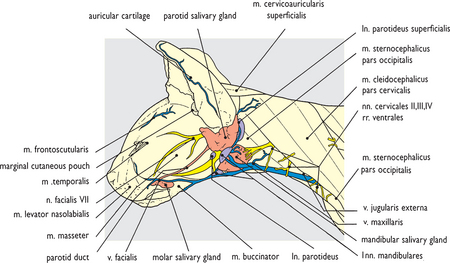

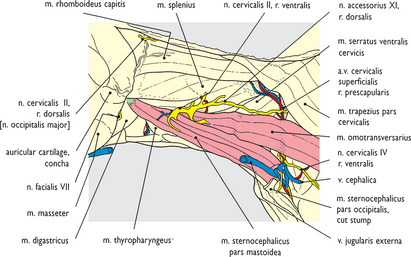

Fig. 10.5 Superficial structures of the head and neck: left lateral view. The head has been skinned and most of the cutaneous musculature has been removed except that on the muzzle (compare with Figs 2.27–2.30 of the dog). Apart from differences in shape and proportion other visible differences include a molar salivary gland, a more pronounced structure than the buccal glands of the dog (Fig. 2.38). An additional, and large, superficial parotid lymph node is present caudal to the parotid gland. NB Lymph nodes in the cat generally are relatively larger than those in the dog.

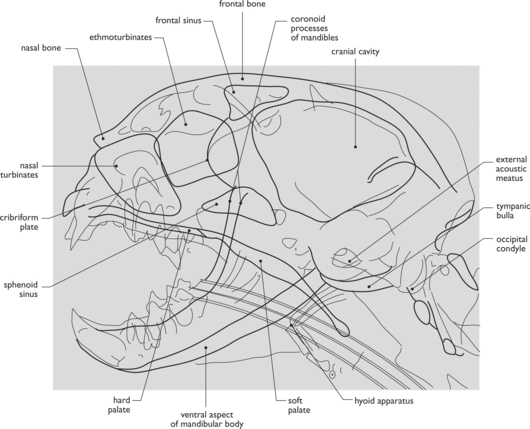

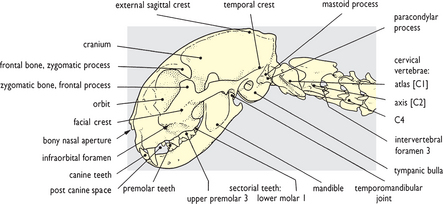

Fig. 10.6 Skeleton of the head and cranial end of the neck: left lateral view. The skull displays a number of differences from the dog (Fig. 2.2). The facial length is reduced in relation to the cranium, brought about primarily by jaw shortening. The dentition is reduced and purely sectorial (shearing), lacking any molar tooth grinding capacity; suppression/reduction in size of the premolar teeth also produces a considerable post-canine space. The enlarged orbit has a practically complete bony margin and faces more rostrally, giving cats the most highly developed binocular vision of all carnivores. An external sagittal crest is short and restricted to the caudal part of the cranium, while the tympanic bulla containing the middle ear cavity is noticeably larger.

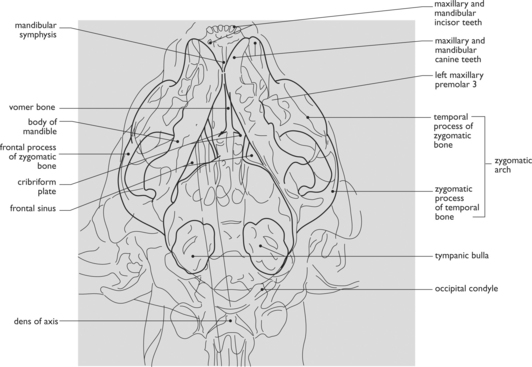

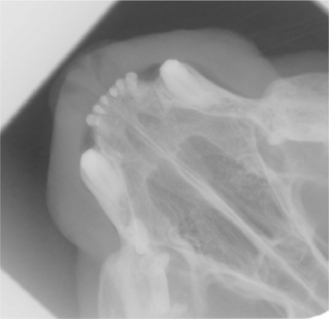

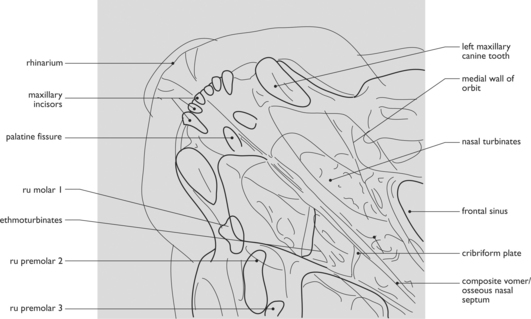

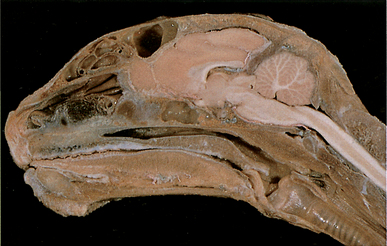

Fig. 10.7 Radiograph of the head and cranial end of the neck: lateral view. The major radiographic features of the head are shown in this picture and in Fig. 10.17. As with radiographs of the dog head (Figs 2.4 and 2.6) detailed internal osteology is omitted, emphasis is placed on identifying the main features and those differing from the dog. The large relative size of the cranial cavity is apparent and the single cavity of the frontal sinus. The dental arches and tooth roots are visible through the jaw bones but few soft features are discernible, although the pharynx and trachea are apparent from the air contained within them (see Fig. 2.7).

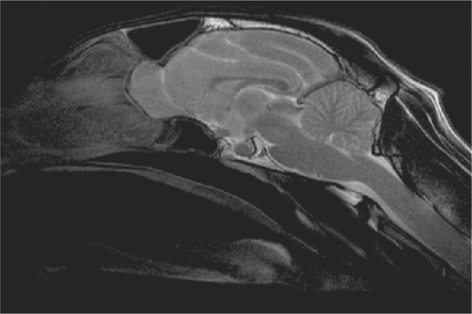

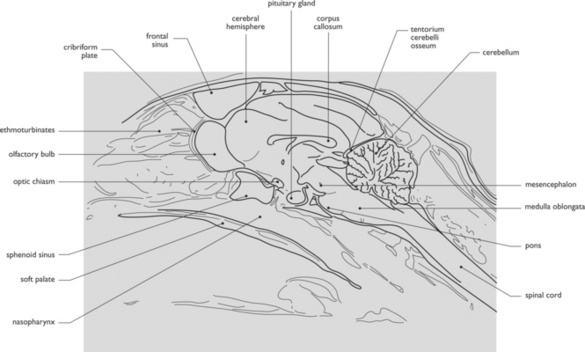

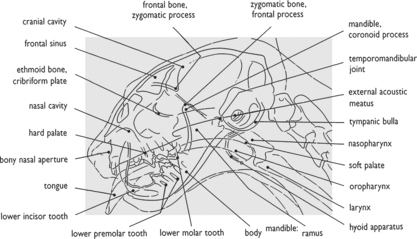

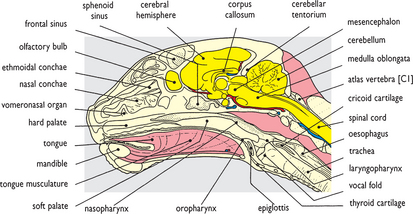

Fig. 10.12 Head and cranial end of the neck in median section: medial view of the right half. The difference in shape and proportion are again apparent in this view of the head comparable to Fig. 2.87 of the dog. A sphenoid sinus is a considerably larger cavity than in the dog skull and lies ventral to an olfactory bulb of the brain, which is relatively much smaller in the cat. The olfactory epithelium in the fundus of the nasal cavity is also less extensive than in the dog, having only half as many olfactory receptors. The larynx displays a somewhat more simple structure with a less pronounced vestibular fold and a barely discernible laryngeal ventricle. Although not visible here, the arytenoid cartilage is also simplified, lacking the corniculate and cuneiform processes of the dog (see Fig. 2.91). The most significant difference in the neck is the absence of a nuchal ligament in the cat.

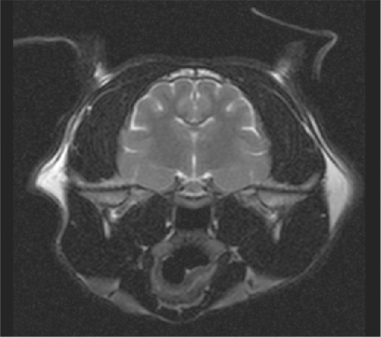

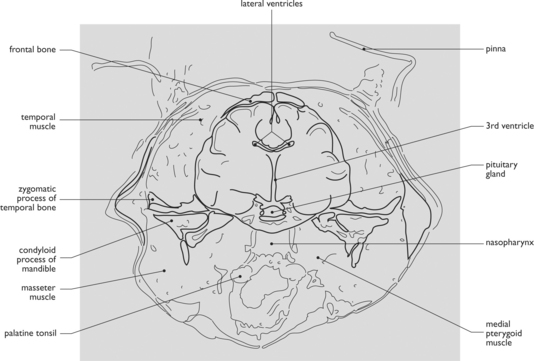

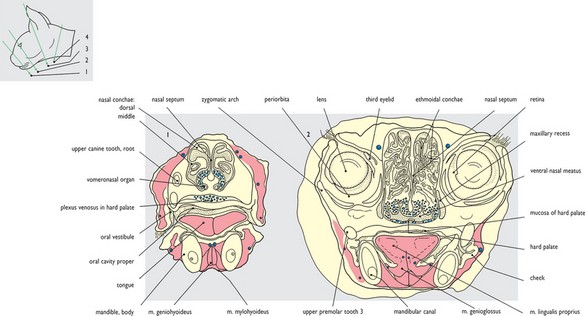

Fig. 10.13 Head in transverse section: (1) Through the nasal region: caudal view; (2) Through the orbits: rostral view. The accompanying sketch of the head in outline shows the approximate levels at which these and the next two sections were taken. The head used for sectioning had already been skinned. In the section through the rostral end of the nasal cavity the vomeronasal organs are apparent (compare with Fig. 2.139 of the dog). The highly vascular nature of the submucosal tissue in the ventral part of the nasal cavity is apparent in this and the section on the right. This second section can be compared with Fig. 2.142 of the dog and shows the relatively greater size of the eyes in the cat. They are also greater in size in relation to the nasal cavity. A cat uses its eyes in combination with the muzzle vibrissae to interpret the environment much as a dog does using its sense of smell.

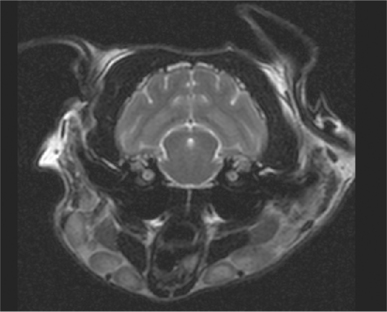

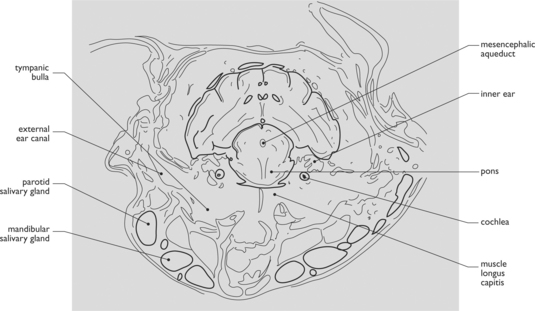

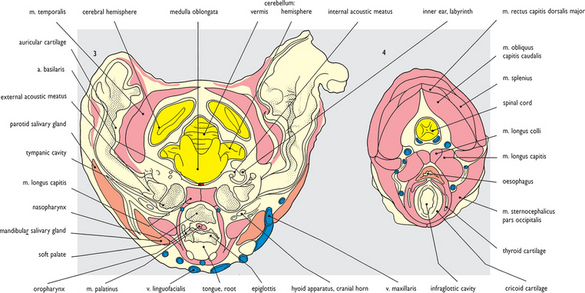

Fig. 10.14 Head in transverse section: (3) Through the auditory regions: rostral view; (4) Through the larynx and cranial end of the neck: cranial view. The section on the left passes through the auditory meatuses which open into the prominent cavities of the middle ear on both sides. The septum subdividing the cavity into two chambers is also apparent, a feature not present in the dog. Ventrally the section passes through the soft palate and caudal end of the oropharynx immediately rostral to the larynx. The oral surface of the epiglottis is apparent. The section on the right passes through the infraglottic cavity of the larynx surrounded by the cricoid cartilage. At this level the entry into the esophagus is directly dorsal to the larynx. Compare with sections Figs 2.145 and 3.37 of the dog.

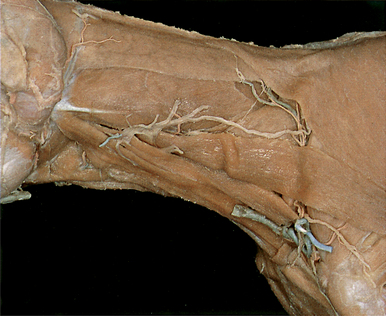

Fig. 10.17 Neck after removal of the cleidocervical and sterno-occipital muscles: left lateral view. The sterno-occipital component of the sternocephalic muscle has been removed, along with the external jugular vein and the mandibular and parotid salivary glands. The strap-like cleidomastoid and sternomastoid components of overlying muscles are left in place ventral to and paralleling the omotransverse muscle. The structures exposed are essentially similar to those shown in Fig. 3.13 of the dog.

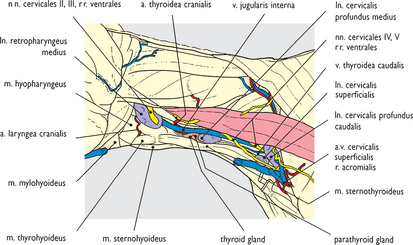

Fig. 10.18 Thyroid gland and lymph nodes of the neck: left lateral view. Removal of the mastoid components of both brachiocephalic and sternocephalic muscles exposes the ‘visceral’ compartment of the neck. Medial retropharyngeal and superficial cervical lymph nodes are evident, and in addition a prominent deep cervical node is displayed midway down the neck, not evident in the dog (see Figs 3.14 and 3.16). Craniomedial to this lymph node the thyroid gland is just visible with a noticeable parathyroid component (see Fig. 3.20). The internal jugular vein is also exposed, a significantly larger vessel than its counterpart in the dog.

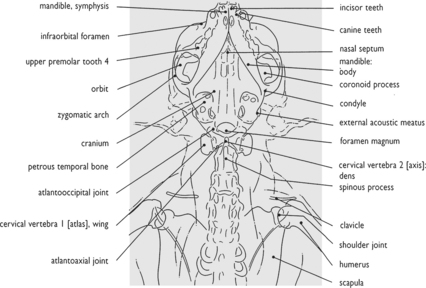

Fig. 10.19 Radiograph of the head, neck and shoulders: ventrodorsal view. The more rounded, bulbous nature of the skull is shown in this view, and the shortened jaws with temporomandibular joints displaying pronounced retroarticular and articular processes. It is comparable with Fig. 2.6 of the dog. The clavicle is a transversely orientated rod with its lateral extremity approximately 1 cm cranial to the greater tubercle of the humerus. It is free in the musculature subdividing the brachiocephalic muscle, although situated on a line connecting sternal manubrium with hamate process of the acromion.

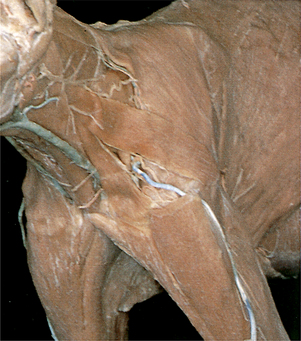

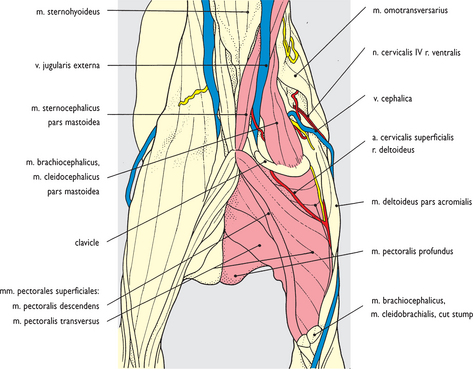

Fig. 10.20 Neck after removal of the cleidocervical muscle: craniolateral view. The cleidocervical component of the brachiocephalic muscle has been removed to give a view comparable to Fig. 3.9 of the dog. The clavicle is exposed, as is the cephalic vein connection with the external jugular vein (an omobrachial vein is absent in the cat). The cleidobrachial and superficial pectoral muscles are displayed; unlike the dog both extend into the forearm. The presence of a clavicle means that a jugular (supraclavicular) fossa is not bordered by pectoral musculature as in the dog.

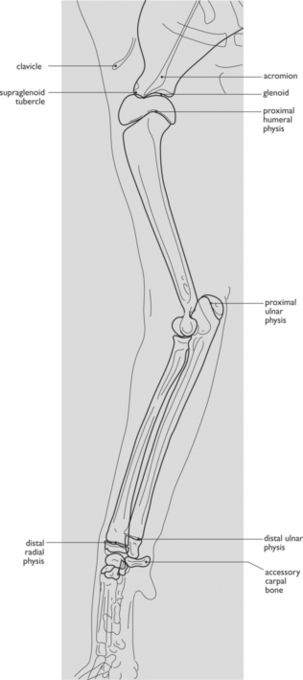

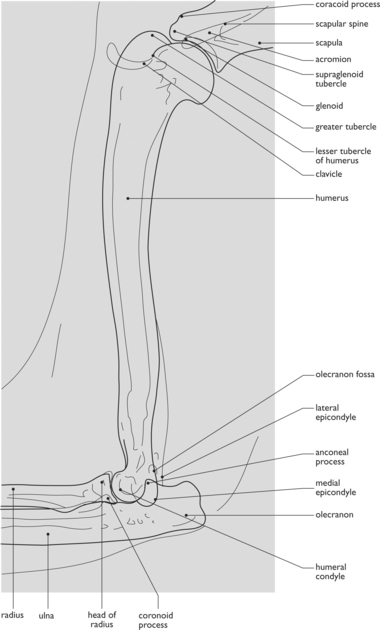

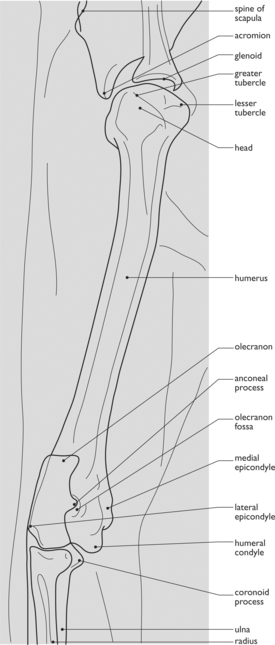

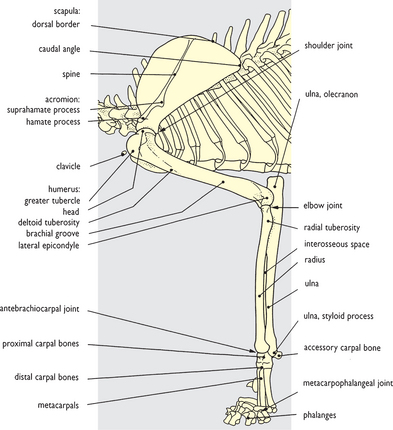

Fig. 10.21 Skeleton of the forelimb: left lateral view. Several differences are apparent in this view in comparison with the dog (Figs 4.8 and 4.47). In addition to the more slender overall nature of the bones, the scapula has a slight tuber projecting caudally from its spine and the acromion is enlarged with hamate and suprahamate processes. At the elbow the olecranon of the ulna forming the point of the elbow is shorter and truncated. A supracondylar foramen is present in the humerus for the passage of the brachial artery and median nerve (see Figs 10.29 and 10.30), although a supratrochlear foramen present in the humerus of the dog is absent in the cat. The accessory carpal bone is not as prominent a structure as in the dog.

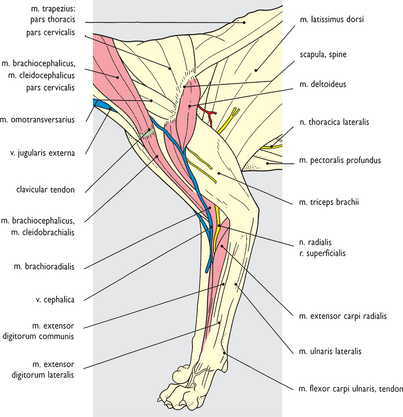

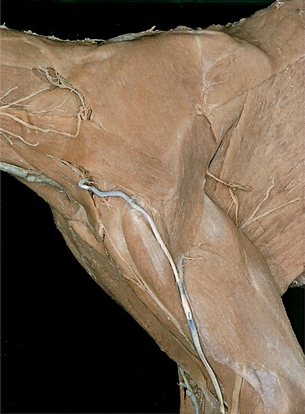

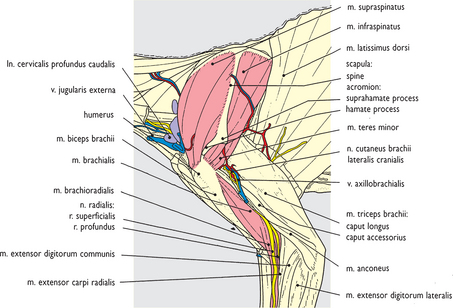

Fig. 10.25 Superficial musculature of the forelimb: left lateral view. Superficial fascia has been cleaned from the limb to expose superficial limb muscles much as in Figs 4.12, 4.51 and 4.82 of the dog. At the shoulder region the absence of a superficial omobrachial venous connection between cephalic vein and external jugular vein is apparent, and the subdivision of the deltoid muscle into spinal and acromial parts is evident. A considerably more prominent brachioradialis muscle is visible more distally in the arm and the radial carpal extensor muscle is a bipartite structure.

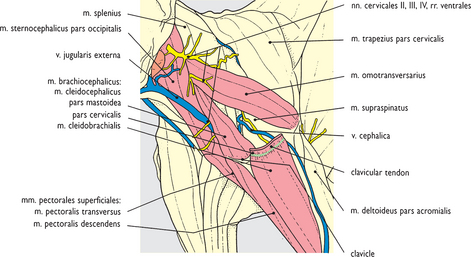

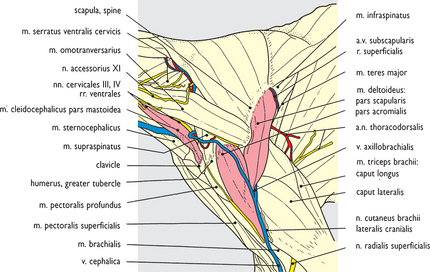

Fig. 10.26 Shoulder and brachium after removal of the brachiocephalic muscle: left lateral view. Brachiocephalic muscle removal has exposed the cephalic vein continuation to the external jugular vein at the base of the neck. The lateral cranial cutaneous brachial nerve (from the axillary) appears caudal to the bipartite deltoid muscle with the axillobrachial vein, and accompanies the cephalic vein in the arm. At the elbow the superficial branch of the radial nerve appears on the brachial muscle and accompanies the brachioradialis muscle into the forearm. Compare this view with Figs 4.12 and 4.13 of the dog.

Fig. 10.27 Shoulder and brachium after removal of the deltoid muscle: left lateral view. In addition to deltoid removal, the trapezius, omotransverse and lateral head of the triceps muscles have also been removed to expose the intrinsic forelimb musculature around the shoulder joint. The subdivision of the acromion process is evident. Cranial to the shoulder a caudal deep cervical lymph node and the superficial cervical nodes are visible. Proximal to the elbow joint removal of the lateral head of the triceps muscle exposes the origin of the brachioradialis muscle and the subdivision of the radial nerve. Compare this view with Figs 4.14 and 4.15 of the dog.

Fig. 10.28 Shoulder and brachium with clavicle exposed: cranial view. The clavicle and cleidomastoid component of the brachiocephalic muscle remain in place after removal of the cervical and brachial components. The sternocephalic muscle is displayed in the midline and the superficial and deep pectoral attachments to the humerus are exposed. More distally in the arm the continuations of cleidobrachial and superficial pectoral muscles onto the forearm have been left in place. Compare this view with Figs 4.21 and 4.23 of the dog.

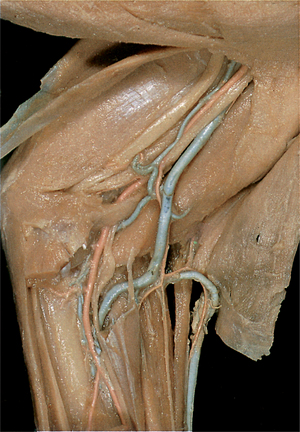

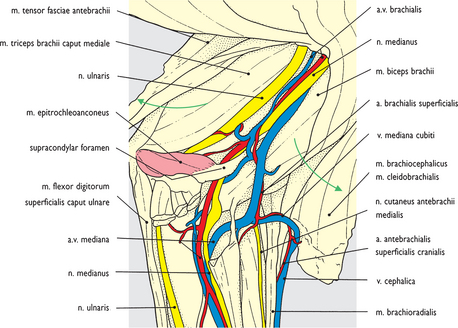

Fig. 10.29 Brachial artery and median nerve at the elbow region of the left forelimb: medial view. The tensor muscle of the antebrachial fascia has been reflected caudodorsally; the cleidobrachial and superficial pectoral muscles craniodorsally. The passage of the brachial artery and median nerve through the supracondylar foramen of the humerus and the epitrochleoanconeus muscle are displayed. Removal of forearm flexor muscles from the medial epicondyle has exposed the median and ulnar nerves and brachial/median artery into the forearm. Compare with Fig. 4.61 of the dog.