31 Cardiovascular emergencies

Acute Decompensated Heart Failure

Treatment

• Reduction of pulmonary venous pressure (hence left ventricular preload), typically through the use of furosemide to promote diuresis and natriuresis

• Glyceryl trinitrate (2% topical preparation): primarily a systemic venodilator reducing preload and potentially therefore alleviating pulmonary oedema

• Emergency treatment of severe dysrhythmias (see Ch. 12), although the emphasis is very much on treatment for congestion in the first instance.

Canine chronic mitral valve insufficiency

Case example 1

Case management

Clinical Tip

• Glyceryl trinitrate paste can be absorbed through human skin and it is therefore important to take certain precautions. These include wearing gloves to apply the paste, and making sure that there are signs on the kennel and kennel sheet alerting personnel that paste has been applied to the patient. The site used must also be clearly identified; the paste is typically applied to clipped or hairless skin, such as the inner aspect of the pinna, and the site used is rotated between applications.

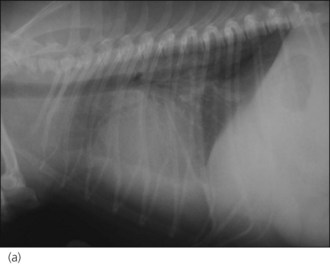

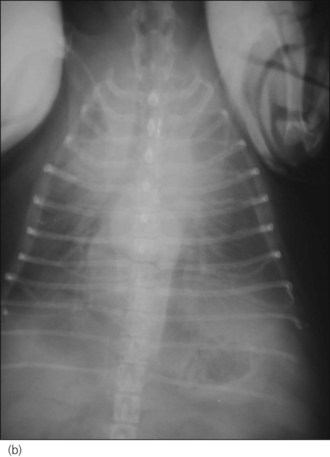

One hour later the dog’s respiration had improved to some extent and he had also urinated. As he was compliant, thoracic radiographs were performed with flow-by oxygen supplementation throughout (Figure 31.1). These findings were consistent with the suspected diagnosis of decompensated left-sided CHF secondary to probable mitral valve insufficiency but there was also evidence of right-sided heart failure.

Clinical Tip

• Right-sided heart failure is relatively common in dogs with chronic mitral valve insufficiency. This is presumed to be due to concurrent tricuspid valve insufficiency as a result of myxomatous degeneration and/or pulmonary hypertension due to persistently elevated left atrial and pulmonary venous pressures.

Canine tricuspid valve insufficiency

• Right ventricular dilation due to increased right ventricular pressure – e.g. secondary to pulmonary hypertension or pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE).