Sophy A. Jesty

Cardiovascular Disease in Poor Performance

Although musculoskeletal and respiratory problems are the most common causes of poor performance in horses, cardiac abnormalities can be documented in up to 21% of all horses presented for poor performance workups. The major difficulty in assessing the contribution of the cardiac system to poor performance is that the cardiac system has such tremendous reserve that abnormalities might only be clinically significant (or appreciable) at higher levels of exercise. For this reason, assessment of the cardiac system in poorly performing horses usually necessitates high-speed evaluations, either on a treadmill or with the horse at full work in its environment.

Cardiac Causes of Poor Performances

A number of specific diseases may contribute to cardiac dysfunction, but broadly speaking, dysfunction can be divided into mechanical dysfunction and electrical dysfunction. Mechanical dysfunction may result in decreased cardiac output and therefore decreased oxygen delivery during exercise. Mechanical dysfunction can result from degenerative valve disease causing significant mitral or aortic regurgitations and leading to volume overload, from myocarditis or cardiomyopathy causing a significant decrease in contractility, or from congenital lesions causing recirculation and volume overload. Electrical dysfunction may result in decreased cardiac output if the arrhythmia is severe enough because contraction and stroke volume are suboptimal, but another more dangerous consequence of electrical dysfunction is sudden cardiac death.

Diagnostics

Echocardiogram

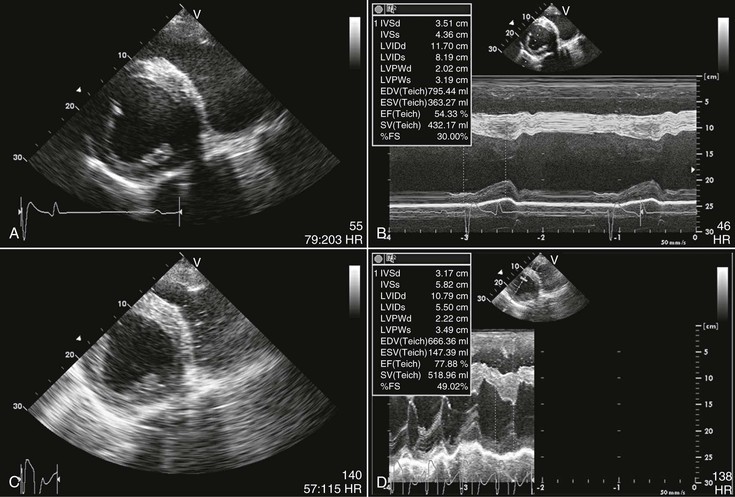

Mechanical changes that occur in the heart during exercise include an increase in size at end diastole, an increase in peak systolic pressure generation, an increase in the speed of contraction during systole, and an increase in the speed of relaxation during diastole. These changes increase stroke volume, enhancing cardiac output and contributing to oxygen consumption and aerobic capacity. Measuring pressures, although ideal for the evaluation of cardiac function, requires invasive cardiac catheterization, making it an unsuitable option for the workup of poorly performing horses. Echocardiography has long been the diagnostic tool of choice for noninvasively assessing cardiac mechanical function in performance horses. Both resting and stress echocardiography should be performed. The specifics of performing echocardiography in horses have been well described elsewhere. A number of echocardiographic changes develop secondary to training, including increased left ventricular dimensions and muscle mass and decreased indices of contractility at rest, for example, fractional shortening and ejection fraction. The stress echocardiographic examination must be made immediately after exercise, and all views must be obtained within 90 to 120 seconds. Values used in the assessment of left ventricular contractility are the most important to obtain before the horse cools down. The best view for assessing left ventricular size and contractility is the right parasternal transverse left ventricular view (Figure 19-1).

The resting echocardiogram provides information regarding chamber dimensions, contractility, valve regurgitations, and congenital lesions, but only provides a diagnosis of important cardiac dysfunction in the most obvious cases. Assessment of contractility is usually made on the basis of fractional shortening, but caution should be taken not to rely too heavily on the assessment of contractility at rest because fractional shortening and ejection fraction actually decrease in fit horses at rest. Echocardiographic examination of racing Standardbreds frequently indicates decreased contractility when the horse is resting but normal contractility during the stress test.

Valve regurgitation increases with age and is fairly prevalent in horses with poor performance. Interestingly, however, most valve regurgitations do not affect performance. Echocardiography reveals mild regurgitations in a high percentage of resting horses; this finding should not be considered a cause of poor performance. In one study, these mild valvular regurgitations actually tended to lessen with exercise.

Occasionally, severe valve regurgitations, severe impairment of contractility, or significant shunting from congenital lesions might be observed on the resting echocardiogram; in these cases, the abnormalities should be suspected to contribute to poor performance. In most cases, however, the echocardiogram of the resting horse is unremarkable. In these scenarios, a stress echocardiogram should be performed to evaluate cardiac mechanical function during exercise. Generally, the horse’s heart rate decreases after intense exercise from more than 220 beats/minute to less than 100 beats/minute within approximately 90 seconds; this is the window in which the stress echocardiogram must be performed. The right parasternal transverse left ventricular view (see Figure 19-1) should be the first echocardiographic view acquired during stress echocardiography. The fractional shortening should be higher than the preexercise fractional shortening and will usually be more than 50%.

Echocardiography is an insensitive means of evaluating subtle alterations in cardiac function. In the future, the stress echocardiogram may be surpassed by alternate means of assessing cardiac function, such as minimally invasive cardiac output monitoring.

Electrocardiogram

The electrocardiogram (ECG) remains the diagnostic test of choice for assessing cardiac electrical function in performing horses. Generally, when speed increases, the heart rate will surge, overshoot, and then settle to a new steady value. Heart rate is positively correlated with velocity within each horse, but measurement of heart rate alone is incapable of stratifying exercise capacity because maximal heart rate is similar in all horses, regardless of fitness level. For this reason, maximal heart rate is considered a poor indicator of performance capacity. What differentiates exercise capacity is the work being done, for example, the speed at a given heart rate. Maximal heart rate in horses plateaus between 220 and 240 beats/minute; beyond that rate, cardiac output begins to decline because of decreased diastolic filling times. As stated earlier, heart rate decreases precipitously with the cessation of exercise in normal horses, halving within 60 to 90 seconds.

The ECG of the resting horse is unlikely to show a cause for poor performance unless the horse has had a tremendous reduction in performance secondary to atrial fibrillation. The most common arrhythmia on the resting ECG of a fit horse is second-degree atrioventricular block, which is a physiologic manifestation of vagal tone in the equine species. Atrial or ventricular premature complexes (VPC), if seen, should increase the index of suspicion of cardiac disease contributing to poor performance, but some horses have occasional arrhythmias at rest that are completely obliterated with exercise.

The stress ECG is a very important part of the cardiac assessment in performing horses, as most cardiac abnormalities found in poorly performing horses are arrhythmic. The assessment of electrical activity can continue throughout the exercise period, rather than being relegated to the immediate postexercise period. The definition of normal with regard to finding arrhythmias during exercise is changing. It was widely assumed in the past that exercising arrhythmias were uniformly abnormal and that they likely contributed to poor performance. Multiple studies have now revealed that arrhythmias are fairly prevalent during the warm-up and cool-down periods, even in horses without performance issues. In the author’s experience, arrhythmias are most likely to arise in the postexercise period at heart rates between 100 and 150 beats/minute. During that time, reemergence of the parasympathetic system is coincident with still-increased sympathetic system activity, leading to electrical heterogeneity and increased risk for arrhythmias. For this reason, the author tends to ignore many arrhythmias in the postexercise period unless they are complex in morphology or timing (Figure 19-2). Most studies show a fairly low incidence of arrhythmias developing during exercise itself, but occasional studies show a fairly high incidence of arrhythmias (especially atrial) during exercise, even in normal horses. To make matters even more confusing, one study found that, although interobserver agreement for classification of arrhythmias (atrial vs. ventricular) was good on resting ECGs, interobserver agreement for classification of exercising arrhythmias was poor (Box 19-1).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree