Chapter 53 Cardiovascular Disease in Great Apes

Historical Perspective

Anecdotal press reports and published journal articles describing ape deaths caused by cardiac disease date back to the mid-20th century.16 However, recognition of clinical signs of cardiac disease in apes, and scientific case reports detailing antemortem recognition of CVD, were scarce through the 1980s. Unfortunately, in both zoological and vivarial settings, clinical recognition of ape cardiac disease was rare, and heart disease was initially detected only in individual apes during postmortem examinations.31 In 1990, a survey of diseases of great apes at the National Zoological Park drew attention to cardiovascular disease.22 In 1994, a survey of gorilla mortality indicated that cardiovascular disease was the primary, or an important contributory, cause of death in 41% of adult gorilla necropsy reports in the Association of Zoos and Aquaria (AZA) North American Species Survival Plan (SSP).18 A series of cases of aortic dissections and a seminal article reporting fibrosing cardiomyopathy in gorillas were published in 1994 and 1995, respectively.12,27 Since then, systematic reviews of necropsy reports from captive zoo gorillas, orangutans, chimpanzees, and bonobos in their respective North American SSPs by a veterinary pathologist with expertise in primate pathology have revealed a similar pattern of myocardial fibrosis, in the absence of coronary atherosclerosis, in the other ape taxa.14 In addition to the 41% incidence in gorillas, 20% of orangutans, 38% of adult zoo chimpanzees, and 45% of bonobos have been noted to have died of CVD.2,5,15,18 Recent reviews have also confirmed the significant incidence of cardiac disease in chimpanzees in laboratory settings.4,13,31 Although detailed analysis of trends and underlying factors is still in progress, CVD appears to be most frequent and severe in apes during mid- to late adulthood, with males affected more than females. Cardiovascular disease, including myocardial fibrosis, has also been recognized in wild mountain gorillas. In the wild, this is usually a contributory, not primary, cause of death, and occurs at a much lower incidence than that seen in captive apes. As of early 2010, neither anecdotal nor comprehensive cardiovascular postmortem reviews of apes in rehabilitation or sanctuary situations have been compiled.

Currently Identified Types

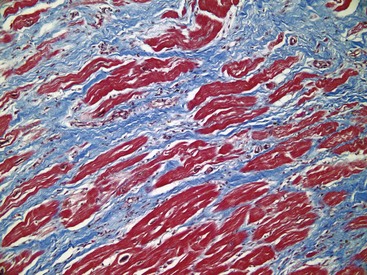

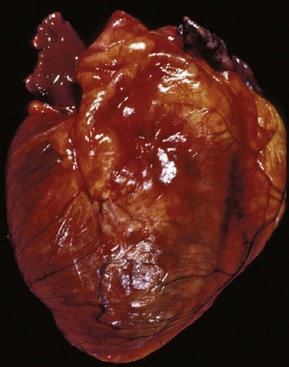

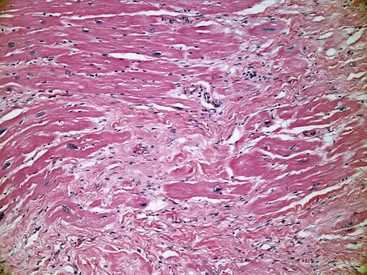

Several types of CVD are seen in apes, but the most common entity, based on published reports and analyses of SSP necropsy data, is characterized by an idiopathic scattered pattern of “myocardial replacement fibrosis with atrophy and hypertrophy of cardiac myocytes, absent or minimal inflammation, and no apparent etiology or associated disease.”27 This pattern has been termed fibrosing cardiomyopathy in gorillas, orangutans, chimpanzees, or bonobos or idiopathic myocardial fibrosis in chimpanzees.11–15,27,31 Grossly, these lesions may be dramatic (Fig. 53-1), but often they are subtle. Histologically (Figs. 53-2 and 53-3), pathologists have noted that these patches of fibrosis arise most frequently near or around small-caliber intrinsic coronary arterioles, which are often thick-walled and hyalinized (arteriosclerosis). Larger coalescent areas of dissecting fibrosis may extend throughout the walls of all chambers, but not to the extent seen with myocardial infarction resulting from major coronary vessel occlusion. In many cases, the heart is enlarged with left ventricular hypertrophy, but in some cases the heart may be dilated and flabby. Myocardial fibrosis, per se, is an end-stage lesion, which does not imply a particular etiology or pathogenetic mechanism. It can develop as a consequence of several different types of injury to the myocardium (hypoxia, ischemia, necrosis, inflammation), and its cause(s), which are likely multifactorial, remain to be elucidated. However, the changes frequently seen in intrinsic arteries of the myocardium suggest that either transient (e.g., catecholamine-induced vasospasm) or systemic hypertension may be present. Many of the apes with myocardial fibrosis die suddenly and unexpectedly while on exhibit, in their night houses, or under anesthesia, presumably due to dysrhythmias, although in some cases more indolent congestive heart failure develops. Other types of ape cardiac and vascular disease that have been reported in the literature or gleaned from the SSP databases include aortic dissection, myxomatous valvular degeneration (endocardiosis, or nodular mucinosis), atherosclerosis, congenital heart defects, infectious myocarditis and valvular endocarditis, and hypertensive congestive heart failure.*

Figure 53-1 Heart of an adult male chimpanzee that died unexpectedly, with myocardial fibrosis.

(Photo credit: Linda J. Lowenstine.)

Figure 53-2 Histologic section of the myocardium of an adult male chimpanzee (H&E stain, ×20).

(Photo credit: Daniel C. Anderson.)

Aortic dissection and sudden death in gorillas was first described in 1970 and its importance was highlighted by the report of eight cases by Kenny and colleagues in 1994.12,21 Since then, an additional four cases have been seen in gorillas6 and three in bonobos.2 In all cases, the tear was in the ascending aorta, not far from the valve, and was not associated with atherosclerosis. The causes of aortic dissection and rupture in apes are not fully understood, but hypertension has been implicated, as it is in more than half of the human cases. Left ventricular hypertrophy seen in these cases suggests either preexisting hypertension or increased workload resulting from the dissection, which is often chronic and forms a double-barreled aorta. Death ultimately is due to failure of the vessel wall, causing cardiac tamponade or intrathoracic hemorrhage. Occasional cases in which vessels other than the aorta (e.g., cerebral or pulmonary vessels) suffer from aneurysms, dissections, thrombosis, or rupture have been reported in the literature or identified in SSP databases. Although CVD in apes is generally not associated with atherosclerosis, occasionally atherosclerosis does occur in apes in the context of coronary arterial heart disease.14 Most often, atherosclerosis is an incidental finding, which is occasionally severe, and usually confined to the descending abdominal aorta and internal iliac vessels. Reports are more common in the older literature than in the SSP databases, perhaps because in earlier times the diets of apes were often modeled on human diets.

Congenital heart defects, including intra-atrial and intraventricular septal defects, have been identified in all ape taxa.8 Often identified in very young animals, a few cases have been identified in apes that survived into adulthood, such as the case of coarctation of the aorta identified in a 7-year-old male gorilla.30

Causes of infective myocarditis reported to have resulted in death in apes include encephalomyocarditis viral (EMCV) infection in orangutans and bonobos, coxsackie B4 viral infection in an orangutan,20 and Chagas disease (Trypanosoma cruzi infection) in a chimpanzee.1 Vegetative endocarditis has been associated with alpha-hemolytic Streptococcus and Gemella spp. in gorillas.6

Possible Etiologies and Pathogenesis

As noted, fibrosing cardiomyopathy is the most frequent form of CVD in apes and myocardial fibrosis is the result of insult to the myocardium. Its presence interferes with cardiac function through altered contractility or conduction. Factors that have been historically and anecdotally reported in great apes, which could logically be associated with some or all of the cardiac lesions seen in apes include the following: obesity or inactivity; dietary factors and chemical imbalances such as high lipids, iron overload, hypovitaminosis D and E, high salt content, and absence of plants eaten by wild apes that might be cardioprotective17,25; personality type and behavioral issues that might be associated with psychosocial stress and catecholamine release; endocrinopathies such as diabetes and hypothyroidism; primary or secondary hypertension; and intercurrent diseases, such as renal disease, dental disease, and osteoarthritis.

Many captive apes, whether born in the wild or in captivity, have had many different diets and social, environmental, and other experiences over their relatively long life spans. Similarly, current zoological exhibits often provide younger apes with larger social setting and enhanced exercise opportunities than were available in the past. Intercurrent diseases are often present in apes with CVD, and the interplay between cardiovascular disease and other diseases is under investigation. In orangutans, there is a statistically significant association between renal disease and fibrosing cardiomyopathy,15 and concurrent renal and heart failure have been reported in a gorilla. It is not known which problem comes first, because chronic renal disease can cause secondary hypertension and primary hypertension can damage the renal vasculature and lead to renal failure. Further characterization of renal disease in apes is warranted to try to answer this question.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree