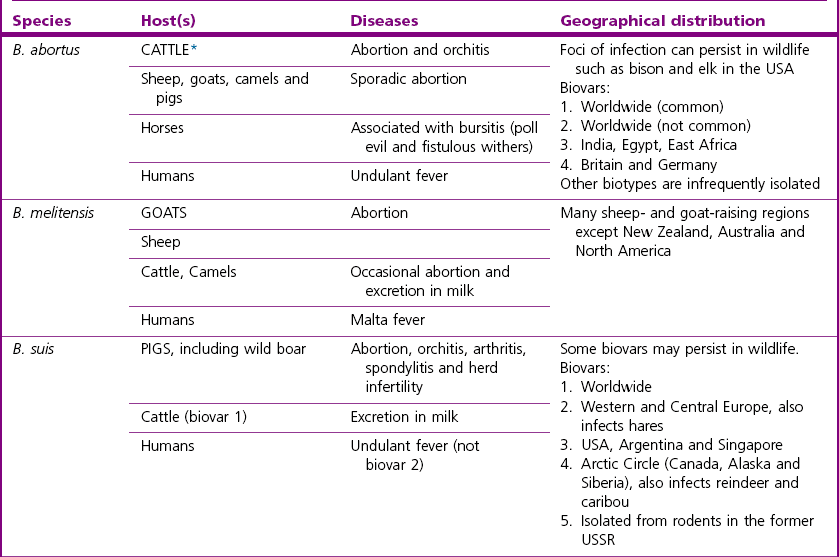

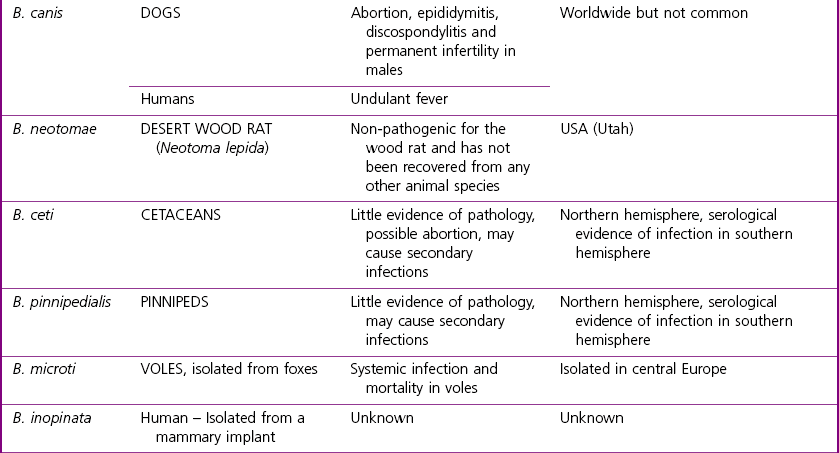

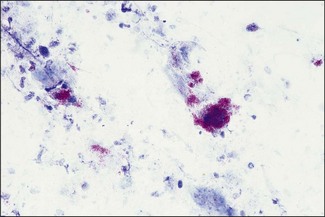

Chapter 23 Brucella species are small Gram-negative rods (0.5–0.7 × 0.6–1.5 µm) that often appear coccobacillary. The brucellae were previously divided into six species based principally on host preference, pathogenicity and differences in biochemical properties. However, DNA–DNA hybridization studies revealed that the species were remarkably homogeneous and thus it was proposed that all species should be regarded as biovars of a single species, Brucella melitensis. This proposal has not gained general acceptance and many workers still adhere to the multiple species nomenclature which describes six nomenspecies: Brucella abortus, B. melitensis, B. suis, B. neotomae, B. ovis and B. canis. The first three of these are subdivided into biovars based on cultural and serological properties. Furthermore, with the recent isolation of Brucella species from marine mammals, two new species, B. ceti and B. pinnipedialis, have been recognized (Foster et al. 2007). Two further species, B. microti and B. inopinata have also been described. The Brucella genome is composed of two circular chromosomes, of approximately 2.1 and 1.2 Mbp, with the exception of Brucella suis biovar 3, which has a single chromosome. Full genomic sequences of B. abortus, B. melitensis and B suis have been published (Halling et al. 2005). The brucellae are non-motile, non-spore-forming and partially acid-fast in that they are not decolourized by 0.5% acetic acid used in the modified Ziehl–Neelsen (MZN) stain. The carbol fuchsin is retained and the brucellae appear as red-staining coccobacilli. The brucellae are aerobic and capnophilic (carboxyphilic), catalase-positive, oxidase-positive (except B. ovis and B. neotomae), urease-positive (except B. ovis) and will not grow on MacConkey agar. B. ovis and B. abortus biotype 2 require media enriched with blood or serum; the growth of the other brucellae is enhanced on enriched media but they will grow on nutrient agar. Table 23.1 lists the Brucella species and indicates the main hosts, diseases and geographical distribution. The principal means of transmission is by direct contact with infective excretors. The route of infection is often by ingestion but venereal transmission may occur and is the main route for B. ovis. Less commonly, infection may occur in utero, via conjunctival mucous membranes and by inhalation. Brucella species occur in both smooth and rough forms, the rough forms being those that lack O-polysaccharide on the cell surface and which belong to the species B. ovis and B. canis. Smooth forms of brucellae can infect, persist and replicate within the macrophages of the host. Soon after infection, before opsonization, the organisms enter the cells following interaction with cell surface microdomains known as lipid rafts (Watarai et al. 2002, Atluri et al. 2011). Once internalized, the organisms reside within the acidified phagosome which they then subvert in ways which are not yet fully understood. Acidification induces expression of the virB operon which in turn controls the expression of a type IV secretion system and its effectors. The outcome includes neutralization of the pH, prevention of lysosomal fusion and multiplication of the organism within the ‘brucellosome’ (Celli 2006). The brucellae are transported to the regional lymph nodes, pass to the thoracic duct and then via the bloodstream to parenchymatous organs and other tissues such as joints. Localization occurs in the reproductive organs and associated glands. Table 23.2 lists major virulence factors of Brucella species which are important for intracellular replication. Table 23.2 Virulence factors of Brucella species important for intracellular replication Smears are made from specimens and stained by the modified Ziehl–Neelsen (MZN) stain (Appendix 1). In smears containing cells, brucellae appear as small, red-staining, coccobacilli in clumps (Fig. 23.1) because of their intracellular growth. The brucellae grow well on 5–10% blood agar but other than foetal abomasal contents and colostrum, the specimens are likely to contain many contaminant bacteria and fungi, so selective media are required. The selective media contain a nutritive blood agar base with 5% sterile sero-negative equine or bovine serum and an antibiotic supplement. The most widely used selective medium is Farrell’s medium which is prepared by the addition of six antibiotics to a basal medium (Anon, 2012a). However, some of the antibiotics in Farrell’s medium may have inhibitory effects on the growth of B melitensis and thus the sensitivity for B. melitensis isolation increases significantly by the simultaneous use of both Farrell’s and the modified Thayer–Martin medium (Anon. 2012a). The antibiotic supplement used in selective media for B. ovis usually differs from that for B. abortus. Terzolo et al. (1991) have suggested that Skirrow agar is a satisfactory medium for both the Campylobacter fetus subspecies and for Brucella species, including the most fastidious ones such as B. abortus biotype 2, B. canis and B. ovis. Formulae for suitable selective media are given in Appendix 2. After three to five days’ incubation on selective serum agar, pinpoint, smooth, glistening, bluish, translucent colonies appear. As they age the colonies become opaque and about 2–3 mm in diameter (Fig. 23.2). Strains of B. abortus, B. suis, B. melitensis and B. neotomae are usually in the smooth form when first isolated. Colonies of rough morphology occur in each of these species on subculture. Brucella ovis and B. canis are always in the rough form. The rough colonies are dull, yellowish, opaque and when touched with an inoculation loop are found to be friable. Brucellae are non-haemolytic on blood agar (Fig. 23.3).

Brucella species

Genus Characteristics

Pathogenesis and Pathogenicity

Virulence factor

Function

Lipopolysaccharide O-chain

Entry to macrophage through lipid rafts; role in prevention of fusion of Brucella-containing vacuoles with lysosomes

Cyclic β-1,2-glucan

Role in inhibition of fusion of the Brucella-containing vacuoles with lysosomes

Vir B type IV secretion system

Late maturation of the Brucella-containing vacuole and fusion with the endoplasmic reticulum to form the ‘brucellosome’

Siderophores

Iron acquisition

Laboratory Diagnosis

Direct examination

Isolation

Identification

Colonial morphology

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Brucella species

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue