Chapter 20 BREEDING, PREGNANCY, AND PARTURITION

SEXUAL BEHAVIOR

Development of Sexual Behavior

Sexual behavior may be recognized in male puppies as young as 3 to 4 weeks of age. They are often observed to mount litter mates of either gender and display pelvic thrusting actions. This is normal behavior and should not be discouraged unless absolutely necessary (Farstad, 1998). Bitch puppies only occasionally show mounting behavior and, if mounted, they usually remain passive. This is considered normal play behavior. Dogs raised with exposure only to humans may respond incorrectly when placed in a breeding situation. The past several decades have seen a trend toward selling puppies when they are quite young. With puppies arriving in their new homes at 5 to 7 weeks of age, it is possible that they are being deprived of some “sex education” they would have received had they remained with their litter mates for a longer time. However, the importance of mounting behavior during play and of interaction with other dogs for the development of normal adult sexual behavior remains speculative.

Courtship

Premating behavior is initiated by the male, and the female responds to these actions. The male is assumed to be sexually attracted to the female by means of pheromones. Most males are aggressive in their behavior, forcing positive or negative responses from the bitch. Courtship behavior includes the male sniffing at the bitch’s nose, ear, neck, flank, and vulvar area while she sniffs the male in return. Licking of the vulvar area, chasing, wrestling, and urinating induce actions of a similar nature by the proestrual female. If the female is in proestrus, further advances by the male, such as standing near her or placing his paw or head on her back, result in the bitch sitting, crouching, growling, snapping, or wheeling around.

Changes in Sexual Behavior in Proestrus and Estrus

In response to increases in plasma estrogen concentrations, the bitch is frequently observed to be more interested in interacting with other dogs, to be restless or nervous, to have an increase or decrease in appetite, to drink more, and/or to urinate more frequently (Farstad, 1998). The increase in urination may aid in dispersing pheromones present in the urine and vaginal secretions that attract male dogs. This pheromone has the chemical structure of methyl-hydroxybenzoate.

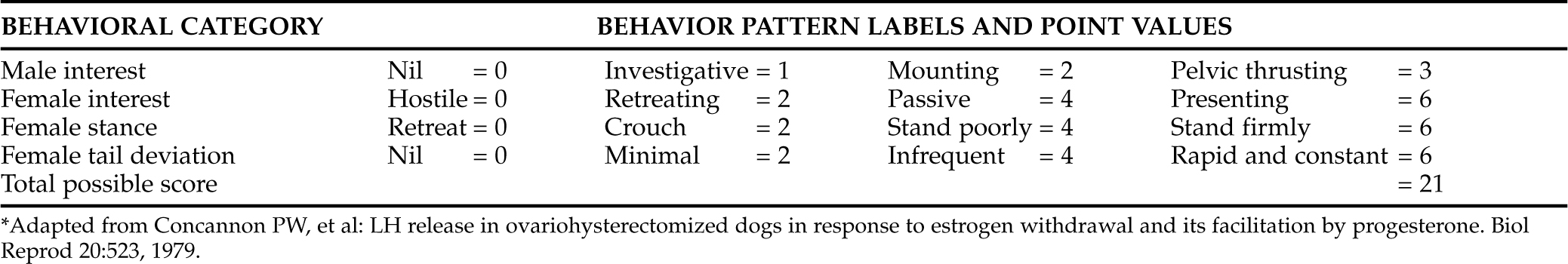

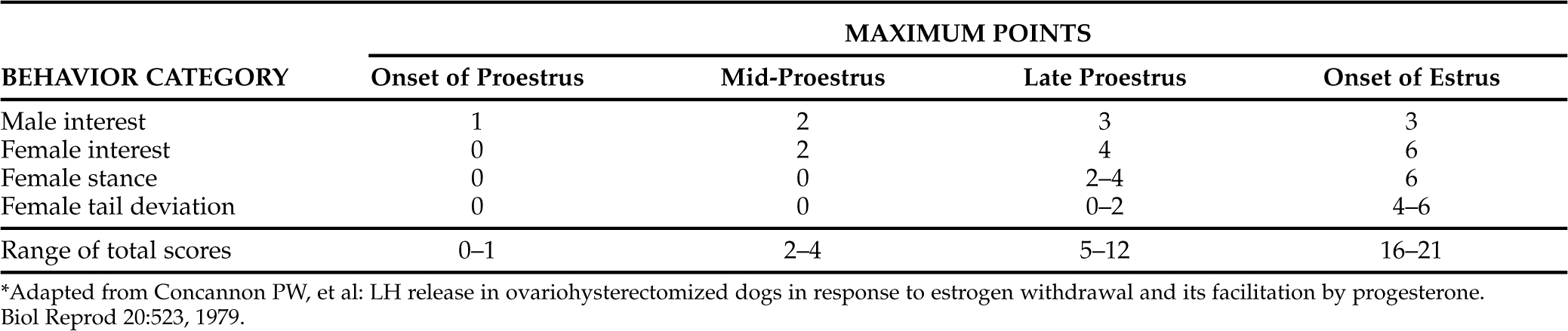

Using a scoring system to assess changes in the behavior of the bitch and the stud, an objective view of changing patterns can be appreciated (Tables 20-1 and 20-2) (Concannon et al, 1979). The female changes from being outwardly hostile to the male, to becoming passive but resistant, and finally to being actively receptive. Obviously, the key behavioral change during this series of events is the female becoming overtly receptive to males. The bitch in estrus stands still when approached by a male and deviates her tail to one side (“flagging”). Some females may present their vulva by elevating it when sniffed by a male. Often contractions may be observed in the perineal and rectal muscles. The bitch may assume a “lordosis” posture if a male places a paw on her back. If the male is timid, she may back up to him, poke him in the side with her nose, paw on his back, or even mount him. As estrus progresses, the female may become less interested in mating. The behavior at the end of estrus is not marked by an abrupt alteration (Farstad, 1998).

TABLE 20-2 TYPICAL MAXIMUM SCORES OF EACH BEHAVIOR CATEGORY AND RANGE OF SCORES FOR EACH STAGE OF PROESTRUS AND ONSET OF ESTRUS*

Normal Mating

The six stages of normal mating are as follows (modified from Farstad, 1998):

The Tie

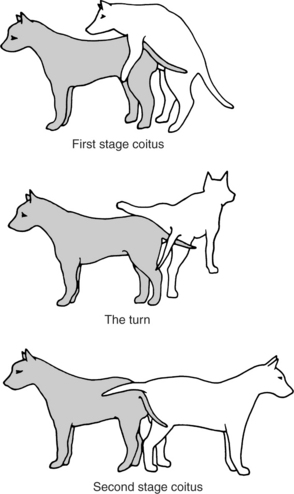

Courtship behavior, as previously described, usually precedes copulation. Courtship may be prolonged by play or chasing activity, or it may consist of the male briefly licking the vulva prior to mounting. Any attempt at mounting by the male typically causes the bitch to stand firmly in place. Mounting (stage 1 of normal mating) consists of the male clasping the flanks of the female, with his forelegs anterior to the hip joints. Intromission appears to be achieved through tentative trial and error pelvic thrusting of the penis toward the vaginal opening (stage 2 of normal mating).

Intromission (stage 2 of mating; stage 1 of coitus; Fig. 20-1) can be accomplished without the male having an erection because the os penis provides rigidity. If the male had an erection prior to intromission, the enlarged bulbus glandis would actually prevent intromission. With normal breeding, intromission takes place, erection then begins (stage 3 of mating), and “stepping” movements of the male’s rear legs are seen. Engorgement of the bulbus glandis takes place simultaneously with the stepping movements. The pelvic thrusting becomes more aggressive, and ejaculation of sperm-free prostatic fluid takes place during the initial 15 to 60 seconds of intromission.

After pelvic thrusting, the male typically dismounts (stage 4; see Fig. 20-1) by placing both front legs to one side of the bitch, lifting one hind leg over her back, and standing tail to tail with her (stage 4; see Fig. 20-1). Full engorgement of the bulbus glandis makes withdrawal of the penis from the relatively small vaginal opening impossible. Thus the male and female are locked, or “tied,” together (Fig. 20-2). This is described as an inside tie. If the male’s erection precedes intromission, the relatively large bulbus glandis cannot enter the vagina, and the result is an outside tie. Dogs that have achieved an inside tie (normal mating) usually remain “locked” together for 5 to 60 minutes. They may actually drag each other around during this period. During the first 1 to 5 minutes of a tie, the male is ejaculating sperm-rich semen. The ejaculate throughout the remainder of a tie consists of sperm-free prostatic fluid.

Factors Affecting Sexual Behavior

ENVIRONMENT.

Male dogs are more territorial than females, and it has been suggested that when a female is dominant to an individual male, he is not likely to succeed in breeding. Male dominance may be pronounced in his territory, therefore females are brought to the male for breeding (Farstad, 1998). Humans may also influence behavior. Some dogs respond positively or negatively to the presence of the owner, whereas others do not. Some dogs allow human assistance during breeding. Some males perform better if another male dog is in the area. Noise, lighting, flooring (traction), and numerous other environmental factors can also influence breeding.

ARTIFICIAL INSEMINATION (AI): GENERAL INFORMATION

Indications for Artificial Insemination

There are numerous reasons for an owner to choose AI over natural breeding, but the primary explanations are that the male and female live some distance from each other or there is a perceived inability for the male and female to breed. This inability may be the result of the presence of a vaginal stricture, which impedes intromission by the male and causes pain during breeding for the female (see Chapter 25). Additional reasons for failure to breed include orthopedic problems, such as disk disease, stifle problems, or muscle weakness.

Less commonly, some owners wish to avoid venereal diseases resulting from contact between their dog and its mate. This seems uncalled for when working with Brucella-free animals. Any agent that could be transmitted from stud to bitch during natural mating is not avoided with AI. However, AI avoids transmission of any agent from the bitch to the stud. Some male dogs (particularly Doberman Pinschers) experience some prostatic bleeding after exposure to a bitch in heat (see Chapter 30). This may be associated with von Willebrand’s disease. In this situation, AI can be performed without any contact between stud and bitch, occasionally avoiding this problem.

Fresh extended and frozen forms of semen are being used with increasing frequency. Obviously, shipped semen must be artificially inseminated into a bitch. Because semen collection is the “rate-limiting” factor in AI, insemination of extended or previously frozen semen remains a relatively simple procedure (Fontbonne et al, 2000).

Success Rates for Artificial Insemination

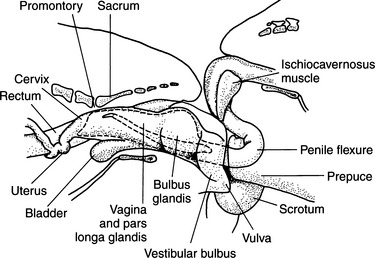

AI may be associated with lower conception rates and smaller litter sizes than would be achieved with natural breeding (Andersen, 1980). This is likely a result of several factors. During natural breeding, semen is pressure forced through the cervix into the uterus and oviducts (see Fig. 20-2), whereas in AI, the semen is placed posterior to the cervix. With natural breeding, uterine contractions aid in semen transport. This is an unlikely event in most AI situations. Also in natural breeding, the duration of the tie may contribute to improving conception rates.

A review of various reports shows that conception rates are less with every method of artificial insemination compared with natural breeding. Natural breeding has been reported to be associated with pregnancies at a rate of 80% to 100%; with fresh semen and artificial insemination, the rate is 62% to 100%; with chilled extended semen and intravaginal insemination, the rate is 60% to 80%; and with frozen semen and intravaginal insemination, the rate is 52% to 60% (Kustritz and Johnston, 2000b). Litter size also appears to be smaller with any insemination method compared with natural breeding (Linde-Forsberg and Forsberg, 1989, 1993; Fontbonne and Badinand, 1993; Silva, 1996).

ARTIFICIAL INSEMINATION (AI): INTRAVAGINAL TECHNIQUE

Collection of Semen

EQUIPMENT.

Semen is usually collected in an artificial vagina. We cut off and use one end of a sterilized, soft rubber, cone-shaped bovine artificial vagina. To this is attached a 12 to 15 ml clear plastic tube (Fig. 20-3). The wide mouth end of the cone is folded over and sealed with rubber cement to make a smooth, nonabrasive edge. A small amount of nonspermicidal lubricating jelly is applied to the inner surface of the rubber cone. This is the only surface that makes penile contact. The only material reused is the bovine rubber cone artificial vagina. Although gas-sterilized equipment is claimed to harm sperm, there have been few problems with reused rubber cones. Perhaps this is because the cone is used primarily as a funnel, and the semen itself is held in the clear, new, disposable plastic tube (Johnston et al, 2001).

ENVIRONMENT.

Most stud dogs can be collected in a clean, quiet room with a nonslippery floor and without any other dog present. However, having a bitch in heat can make collecting semen from a small percentage of males easier. It has been suggested that the presence of a “teaser” bitch or use of the canine pheromone may improve the quality of semen collected (Kustritz and Johnston, 2000b). This concept has no scientific support.

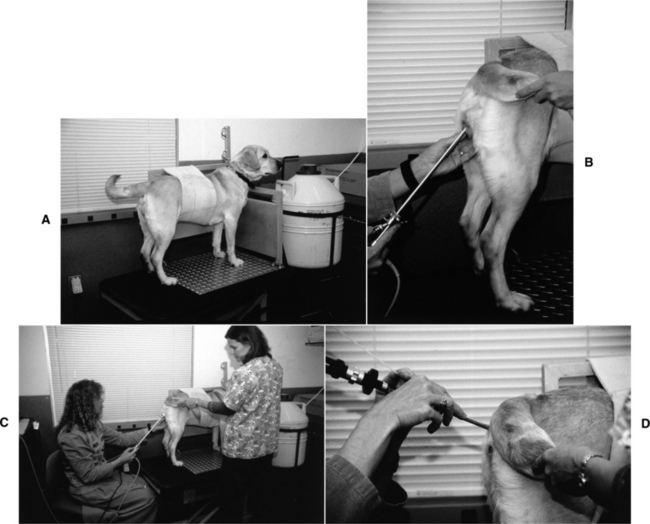

PROTOCOL.

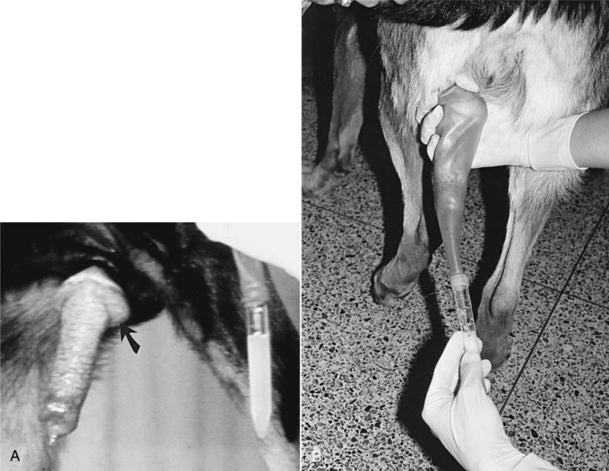

Once the penis and bulbus glandis are extruded from the sheath, the collector firmly holds onto the base of the penis, proximal to the bulbus glandis. The thumb and index finger are used, providing both massaging movements and downward pressure around the base of the bulbus glandis (Fig. 20-4). During or immediately after achieving an erection, aggressive pelvic thrusting movements by the stud, which accompany the onset of ejaculation, may make it difficult to place the artificial vagina over the penis. However, the pelvic thrusting is typically short-lived (5 to 15 seconds) and, as previously described, the initial 5 to 30 seconds of ejaculate consists of sperm-free prostatic fluid. There is no need to collect this sperm-free fluid; therefore there should be no alarm if pelvic thrusting interferes with collection of the initial fluid of the ejaculate.

The sperm-rich second fraction of the ejaculate usually begins as the pelvic thrusting stops. At the same time, moreover, many males step over the collector’s arm, as if dismounting the bitch. The collector should simply allow this instinctive movement by the male and bring the penis between the rear legs of the stud for continued collection (Fig. 20-4, B). Semen is usually collected for 2 to 5 minutes. The clear plastic tube should already have been connected to the rubber artificial vagina, and the apparatus can be held under the collector’s arm during the initial stimulation period to provide some warmth. Canine semen is relatively resistant to cold shock, alleviating the need for warm water tanks or incubators for holding semen.

Use of a clear plastic collection tube allows visualization of the semen. We usually collect semen for approximately 2 to 4 minutes, keeping one hand over the plastic to avoid excessive exposure to light. As long as the ejaculate is obviously whitish or cloudy (normal and sperm rich), it continues to be collected. Whenever the ejaculate becomes clear (sperm free), collection can be discontinued. If the collector is not certain whether the male has stopped ejaculating the sperm-rich fraction, collection should be stopped after 3 to 4 minutes (Farstad, 1998). Continued collection only dilutes the sperm with the phase 3 clear, sperm-free prostatic fluid, resulting in cumbersome fluid volumes. Alternatively, the collection system containing sperm-rich semen can be exchanged for a clean system if there is any need to evaluate the prostatic fluid.

Insemination Procedure

The male is taken out of the room to avoid any distractions. Wearing sterile gloves, the inseminator draws the semen into a sterile, new, 6 ml syringe. Every attempt should be made to stop semen collection as soon as sperm-free prostatic fluid is seen so as to avoid an excessive volume. The smaller the volume (less than 4 to 6 ml is excellent), the less leakage of semen from the vaginal vault of the bitch after AI. Once the semen is in the syringe with at least 1 to 2 ml of air, a new clean urethral catheter is attached (see Fig. 20-3). The owner is usually given the job of holding the bitch’s head and keeping the bitch’s tail to one side.

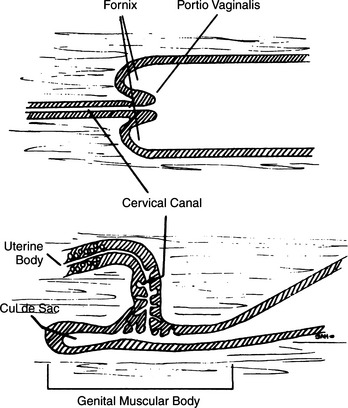

A gloved, nonlubricated index finger (except in very small dogs, in which case the little finger is used) is inserted into the vaginal vault, palm up. If lubricant is used, it must be nonspermicidal. Lubricant is often not needed, or only a tiny amount is necessary due to the normal vaginal discharge associated with estrus. The urethral catheter is then slid over the top of the finger and passed into the vaginal vault until resistance is met. Because of the unique anatomy of the canine cervix (Fig. 20-5), it is difficult at best to pass a catheter through the cervix and into the uterus (Roszel, 1992). Therefore the goal should be to pass the urethral catheter cranial to the “cervical os.” Realistically, the inseminator passes the catheter as far cranially as possible, having first estimated the length of the catheter against the distance from the vulva to the cranial edge of the pelvic floor. The index finger aids in avoiding both the clitoral fossa and the urethra. The catheter follows the dorsal curvature of the vaginal vault. Semen is flushed into the vaginal vault and cleared with the air that was also in the syringe. Once this procedure has been completed, the catheter is removed.

Intravaginal Insemination with Previously Frozen Semen

Experience has demonstrated that intravaginal insemination of previously frozen semen consistently fails, in part because this sperm loses the ability to migrate through the cervix. However, more recently, one study demonstrated success with intravaginal insemination of semen that had been frozen in Triladyl (Minitub, Germany) to which 0.5 ml of Equex STM paste was added. Prostatic fluid or TALP was also added to the thawed semen (Nothling et al, 2000).

ARTIFICIAL INSEMINATION (AI): TRANSCERVICAL INSEMINATION (TCI)

Background

HISTORY.

Although the technology for freezing semen was developed long ago, use of this method has increased recently. Explanations for this include: an improved ability to “time” breedings; an understanding that the freezing process dramatically reduces the ability of sperm to migrate through the cervix; and the development of practical, nonsurgical, transcervical insemination techniques (Farstad and Anderson-Berg, 1989; Wilson, 2001). Direct surgical insemination into the uterus is possible, but such procedures are usually limited to one insemination, and many veterinarians are reluctant to become involved with a method with obvious surgical and anesthetic risks.

ANATOMY.

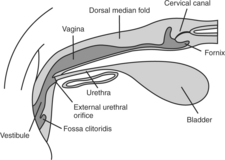

Familiarity with canine anatomy is required to become competent with TCI. The vagina of the bitch is relatively long compared with other species. The total length of the vagina in the typical 11 kg female has been estimated to be 10 to 14 cm, and for large breed dogs it can be as long as 30 cm (Pineda et al, 1973). Visualization of the cervix is normally compromised by the dorsal median fold (Fig. 20-6), which extends caudally 2 to 4 cm from the cervix. The paracervix is the term used to identify this portion of the cranial vaginal vault (Lindsay, 1983). The caudal portion of the paracervix ends in a narrow “tubercle,” which has the appearance of a cervix when viewed from the rear; this explains why some individuals incorrectly assume that they can routinely visualize the cervix with various scopes. Cranially, the paracervix ends in a fornix. The fornix is a slitlike space cranioventral to the true cervix and is a blind pouch (see Figs. 20-5 and 20-6).

The cervix lies diagonally across the uterovaginal junction and is directed craniodorsally, connecting the vagina with the uterus. Thus the external opening of the cervix faces the floor of the vagina and is located in the center of a rosette of furrows in most bitches. This angle, plus the small diameter of the cervical canal, creates natural obstacles to an attempt to pass a catheter from the vagina into the uterus (Wilson, 2001). Maiden bitches present a greater challenge because their cervical lumen is, on average, narrowest.

“New Zealand” Endoscopic Technique

INTRODUCTION.

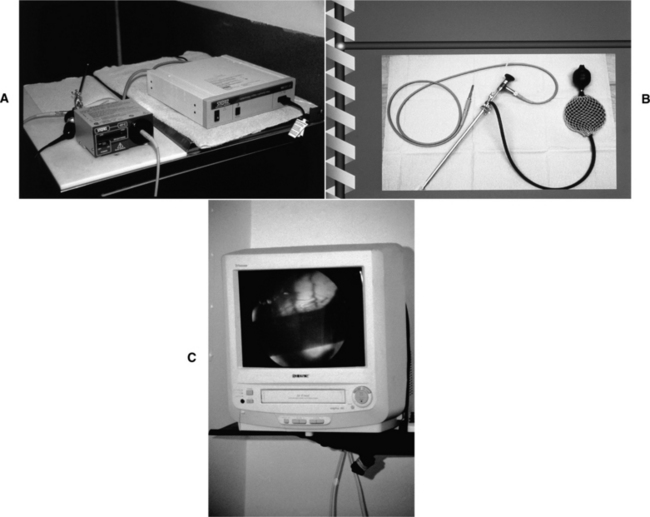

The technique described here (Wilson, 1992, 2001) requires time, patience, and practice. A thorough knowledge of reproductive tract anatomy is indispensable. Practicing with a trained individual who can observe the endoscope and catheter via an attachable video camera is quite helpful. The equipment described in the next paragraph is easily cleaned and disinfected.

EQUIPMENT.

The equipment used is a rigid, extended length cystourethroscope (Storz, Coleta, CA). This tool has a telescope with a 30-degree oblique viewing angle, a sheath, a bridge, and a cold light source. The working length of the assembled endoscope is 29 cm (Fig. 20-7). This tool can be used with virtually any breed, regardless of size. A nonessential video camera can be attached. Finally, the actual insemination is accomplished with a 6 or 8 French urinary catheter (the 6 French size is sometimes needed for small or maiden bitches). The best technique for this procedure also uses a specially designed hydraulic platform table that provides a tie point to the dog’s collar and an abdominal band that prevents sitting or any sideways movement. The table can be placed at a level that gives the operator optimum positioning during the procedure (Fig. 20-8).

PROCEDURE.

The endoscope is placed into the vagina and visually advanced through the vaginal folds. When a bitch is in proestrus or early estrus, the rounded vaginal folds (see Chapter 19) that tend to fill the vaginal lumen can impede placement of the endoscope. Dehydration of these folds, associated with continuing estrus, allows better visualization. The caudal tubercle of the dorsal median fold (DMF) is a prominent landmark (see Fig. 20-6). The lumen may be quite narrow in this region, sometimes requiring manipulation of the endoscope to the widest space and occasionally causing the endoscope to be pushed lateral to the DMF rather than being maintained in the more ideal midline. The vaginal cervix may not be obvious because it faces caudoventrally or ventrally. To locate the cervical os, the operator usually must advance the scope under the cervical tubercle. The os can be identified as being centered in the rosette of furrows or by observing the flow of serosanguineous uterine fluid through the cervix. The positioning of the os may appear to change during estrus as dehydration of vaginal folds progresses.

In some bitches, the amount of space in the paracervix is too small to accommodate the endoscope. This problem may be encountered in some small breed dogs and with some maiden bitches. Endoscopes with a smaller diameter may be used, although such scopes have a shorter length. The shorter length limits use of these scopes to small breeds. The longer scope may be difficult to manipulate in small breeds, sometimes requiring their sedation. Even when the scope can be positioned without difficulty, some bitches are not easily catheterized due to unusual anatomy, poor visibility secondary to vaginal discharges, or lack of cooperation.

SAFETY.

The procedure is safe. Trauma caused by the scope or catheter would be extremely unusual if a bitch is in estrus and would be most likely the result of abnormal preexisting problems in the vaginal tract or undo force on the equipment by the operator. Whenever the bitch shows discomfort, the procedure should be halted and the scope repositioned. Resistance to infection is heightened during estrus, and the likelihood of this procedure creating a greater risk of infection than natural breeding seems unwarranted (Watts et al, 1996). However, the equipment must be cleaned properly, and this discussion focuses on the bitch in estrus. Risk of infection is greater in the other phases of the estrous cycle.

RESULTS.

The technique described here allows intrauterine deposition of semen. It also allows repeated inseminations (unlike surgical semen placement). Conception depends on placement of the semen in the uterus, correct timing, quality of the semen, and fertility of the bitch. Conception rates in excess of 80% have been described (Sirivaidyapong et al, 2000; Wilson, 2001).

FERTILIZATION

The Egg

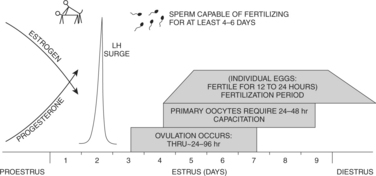

Understanding the temporal relationships between ovulation, fertilization, and breeding behavior of the bitch may aid in caring for dogs used in breeding programs, specifically dogs suspected of being infertile. In an “average” bitch, there is a consistent sequence of events leading to pregnancy as she progresses through proestrus and into estrus (standing heat). The luteinizing hormone (LH) peak occurs on the second day of standing heat (Concannon and Yeager, 1990). Twenty-four to 96 hours later, averaging the fourth day of standing heat, ovulation begins. Studies indicate that it takes 72 hours for approximately 75% of the follicles to rupture and 96 hours after the LH surge for more than 90% of the follicles to rupture (Wildt et al, 1978). The eggs released are “primary” oocytes that must undergo two meiotic divisions, requiring 48 to 72 hours, before they can be fertilized. Once mature, the fertile life of “secondary” oocytes may be as brief as 24 to 72 hours (Phemister et al, 1973). Fertilization, therefore, on average, takes place on day 7 of estrus (standing heat).

Eggs are fertilized in the average bitch from the middle of the fifth day of standing heat through the ninth day after the beginning of standing heat. Minimal fertility may persist for 1 or 2 days after the beginning of diestrus, as determined by vaginal cytology (Fig. 20-9). However, because most bitches are not precisely “average,” predicting a precise day of fertilization is difficult (Concannon et al, 1989b), therefore no single day is optimal for a stud to breed the normal bitch. Conception usually occurs, however, with a single natural breeding (Figs. 20-9 and 20-10). When 21 bitches were bred twice, once 36 hours prior to ovulation and once 84 hours after ovulation, each time to a different male, only two of the bitches conceived pups from only the second male (Doak et al, 1967). This suggests that some advantage is gained by breeding early in estrus. The primary goal in breeding should be to obtain at least one mating every 2 to4 days during standing heat. Embryonic cleavage between 2 and 16 cells occurs more rapidly after fertilization of more mature versus less mature oocytes, explaining in part why gestation length is similar whether mating occurs before or after ovulation (Bysted et al, 2000; Concannon et al, 2000).

The Sperm

Knowing the potential life span of canine sperm in the uterus of the bitch is also helpful in understanding breeding management and conception. Sperm from a natural mating may reach the oviduct of the bitch within 25 seconds of ejaculation. More important, canine sperm has a relatively long survival period in the uterus. Undiminished concentrations of motile sperm have been found in the uterus 4 to 6 days after a single breeding. Breeding trials have suggested that canine sperm has a fertile intrauterine life span of 6 to 7 days after breeding (Doak et al, 1967; Concannon et al, 1983). Also, motile sperm have been observed in bitches as late as 11 days after a single mating. Sperm requires 7 hours of capacitation in the uterus. Once this time period has passed, sperm can penetrate the zona pellucida. In vitro, sperm can enter the vitellus and undergo nuclear decondensation in immature (primary) oocytes (Mahi-Brown et al, 1982).

The length of time that fertile eggs (primary and secondary oocytes) remain in the oviducts (several days), coupled with the longevity of sperm capable of fertilization after a single mating, suggests that a single breeding is quite likely to result in conception (see Figs. 20-9 and 20-10). Single matings per bitch per cycle, beginning 2 days prior to the LH surge through 5 days after, have resulted in conception in 95% of healthy bitches. Maximum litter sizes have been observed among bitches bred once 4 to 10 days before the onset of diestrus. Conception rates fall to 80% if the single breeding takes place 6 days after the LH surge, and the percentage of successful conceptions continues to fall to virtually zero 10 days after the LH peak. Litter size also decreases. The average onset of diestrus was the eighth day after the LH surge. These various factors agree with the tentative scheme outlined in Fig. 20-9 and with the results of early research (see Fig. 20-10).

BREEDING MANAGEMENT OF THE BITCH

Age, Silent Heat, Split Heat, Inexperience, and Ovulation Failure

SPLIT HEAT.

A split heat involves the bitch that has proestrual vaginal bleeding and vulvar swelling and that attracts males. The bitch experiencing a split heat may or may not exhibit standing heat (estrus) before proceeding into an apparent diestrus. However, these bitches begin proestrus again 2 to 10 weeks later. This may be repeated several times. Evidence indicates that each “apparent” proestrus is associated with follicular development and estrogen secretion. However, ovulation does not take place, and the follicles become atretic. A new group of follicles then develops, reexposing the bitch to increases in circulating estrogen concentrations and the signs of another proestrus (Okkens et al, 1992).

INEXPERIENCE AND OVULATION FAILURE.

It is not surprising that the young bitch, even one apparently in estrus, may not respond to a stud as would be expected. The inexperienced bitch and stud, controlled by inexperienced owners, may fail to achieve a tie, with one of two healthy dogs taking the blame. In addition, some bitches may proceed through an apparently normal cycle, including normal breeding, but fail to ovulate. The diagnosis of inexperience cannot be confirmed but is reserved for young bitches and dogs. The diagnosis of ovulation failure can be indirectly determined if estrus is not followed by a typical 60- to 90-day period of progesterone dominance (see Chapter 19).

Breeding Intervals per Estrus and When Breeding Should Begin

GOAL IN BREEDING.

The simple goal in any breeding program is to have a sufficient number of sperm present in the uterus and oviducts to achieve the optimal chance for fertilization of mature eggs. Mature oocytes are typically fertilized during the 3 to 8 days after the LH surge, representing a period beginning 24 to 48 hours after ovulation of primary immature oocytes (see Fig. 20-9). Using reliable, clinically practical methods for estimating the day of the LH surge can be quite valuable. These criteria include behavior observation, vaginal cytology, vaginoscopy, and serial serum progesterone concentrations. None of these four criteria is considered perfect, but when used together, they enhance the chances of a bitch being inseminated at the proper times. Use of a direct LH assay is possible. Furthermore, normal sperm are known to survive and retain the capacity for fertilizing mature oocytes in the oviducts for at least 4 to 6 days and in some instances for as long as 11 days. Using this information, a breeding program can be offered to a client with reasonable confidence of success.

CRITERION 2: VAGINAL CYTOLOGY.

Vaginal exfoliative cytology provides a good reflection of rising plasma estrogen concentrations. Cytologically, full estrogen effect is seen as greater than 80% of epithelial cells being the superficial type, with no neutrophils present on the smear. This is a smear typical of standing heat. Whenever the number of superficial cells on vaginal cytology exceeds 60% to 80% of the exfoliated cells, the bitch should be brought to the male to see if she will allow breeding. This is also the time to begin AI. As described in Chapter 19, vaginal cytology is a simple, inexpensive, and reliable means of evaluating the bitch. The recommendation is to continue exposure to the male or breeding (or both) every other day (daily with AI) as long as the percentage of superficial cells remains above 80% and to discontinue breeding when the percentage of superficial cells decreases below 60%; that is, breeding is continued until diestrus is obvious on vaginal cytology. Vaginal smears should be monitored beginning with the second or third day of proestrus to avoid initiating contact with a male too late.

CRITERION 3: VAGINAL ENDOSCOPY.

Vaginoscopy can be used to aid in staging the ovarian cycle of the bitch for timing natural breeding or AI. As reviewed in Chapter 19, the vaginal mucosa of the bitch in proestrus appears rounded and edematous. Subtle wrinkling (crenulation) of the mucosa is associated with the preovulatory LH surge. This is the time to begin breeding or AI. Breeding (assuming that the bitch is standing for the male) or AI should be continued through the phase of maximal mucosal crenulation, seen as angulated folds of vaginal mucosa with sharp profiles. Breedings or AIs should be discontinued when the vaginal mucosa again becomes flaccid and smooth, with a patchy red and white surface. This shift back to a smooth mucosal surface is typically observed 6 to 10 days after the LH surge (Lindsay and Concannon, 1986). In contrast to the other three primary criteria in determining breeding or AI dates, observation for crenulation in the vaginal mucosa is subjective, and experience in detecting subtle changes is beneficial.

CRITERION 4: SERUM PROGESTERONE CONCENTRATION.

In-hospital test kits for determining the serum progesterone concentration are widely available, and reference laboratories are providing rapid turnaround of submitted samples, making progesterone a useful tool for timing ovulation. It is recommended that serum be assessed beginning 3 or 4 days after a bloody vaginal discharge is observed or within 1 or 2 days of detection of greater than 60% superficial cells on vaginal cytology. Ideally, the first sample documents plasma progesterone concentrations less than 1 ng/ml. The bitch should then be assessed daily or every other day until a distinct rise of greater than 1 ng/ml is noted, which suggests that the LH surge is occurring or has occurred (Eckersall and Harvey, 1987; England et al, 1989; Hegstad and Johnston, 1992; Manothaiudom et al, 1995; Goodman, 2001). Breeding or AI should then begin and continue every other day (or daily with AI) for 8 days or until another criterion (vaginal cytology or behavior) demonstrates that breeding should be discontinued.

The serum progesterone level begins to rise concurrently with the LH surge, reaching 1.0 to 1.9 ng/ml (3.1 to 5.9 nmol/L) on the day the surge takes place. The day after the LH surge, 1 day before ovulation, the serum progesterone concentration is 2.0 to 3.9 ng/ml (6.2 to 12.1 nmol/L). On the day of ovulation, the serum progesterone concentration is 4.0 to 10.0 ng/ml (12.4 to 31.0 nmol/L). Several enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for assessing the progesterone concentration are available for use in the veterinary hospital (i.e., PreMate, Camelot Farms, College Station, TX; Status-Pro, Synbiotics, Malvern, PA). Critical evaluation of these kits has demonstrated poor correlation with radioimmunoassay (RIA) systems, specifically in the 1.5 to 10.0 ng/ml range. This is the range of greatest importance for ovulation timing. Whenever possible, therefore, laboratory RIA testing should be used (Bouchard et al, 1993; Kustritz and Johnston, 2000a).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree