Chapter 11 Behavior of the stallion

Chapter contents

Free-ranging harem-maintenance behavior

Observations of free-ranging horses have provided numerous examples of the ways in which we restrict the behavior of managed stallions, restrictions that can lead to aggression and reduced fertility, libido and behavioral compliance.

Herding is usually employed by stallions to move the family group away from a threat such as a single stallion or another group. Free-running stallions typically herd together a harem of mares as a relatively stable social unit. They tend to recruit and retain mares most effectively when 6–9 years of age.1 The upper limit on the size of harems relates to the fact that if a stallion monopolizes too many mares he loses the ability to dissuade other males from performing sneak matings.1 Sometimes juvenile males, old stallions and, more occasionally, mares cooperate with the harem stallion in his herding activities. This herding behavior can be used to tighten a band or to move interlopers out of or, occasionally, non-member females into the group. Herding, characterized by the neck snaking from side to side, is also seen during courtship, its aim being to transiently distance the mare from the harem for copulation.2 Cohesion of the group contributes directly to biological fitness because, for example, invasion by non-member stallions can induce abortion and bring mares into season for subsequent mating by invading males.3 Vigilant herding is most evident after a harem mare has foaled. At this time the stallion works to maintain a greater than usual distance from other bands, perhaps because this helps him to capitalize on the fact that free-ranging mares peak in fertility during the foal heat.4

Sometimes low-ranking males, notably the sons of low-ranking mares, form lifetime alliances in which both stallions have mating rights and cooperate to defend their mares from intruding males.5 The balance of the pair is rarely equal, with the subordinate stallion siring approximately one quarter of the harem’s brood. This compares favorably with the success of sneak matings that represent the only alternative for non-alpha males.5 However, reciprocal altruism and mutualism do not occur in multi-stallion groups. Linklater & Cameron6 reported a positive relationship between aggression by the dominant stallion toward subordinate stallions and the subordinates’ effort in harem defense, which was negatively correlated with the extent to which these stallions were seen to consort with harem mares. Perhaps because they undergo more social flux than single-stallion groups, multi-stallion groups are associated with more aggressive interactions and reduced foaling rates – hence, the suggestion that there is selection pressure for single-stallion groups.7 The various agonistic responses that arise between stallions appear in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1 Features of the agonistic ethogram (as described for bachelors11) that are particularly common among and between stallions

| Response | Description |

|---|---|

Boxing  | Two stallions in close proximity simultaneously rearing and striking out with alternate forelegs toward one another |

Circling  | Two stallions closely beside one another head-to-tail, pivot in circles, usually biting at each other’s flanks, groin, rump and/or hindlegs. With prolonged circling, the stallions may progress lower to the ground until they reach a kneeling position or sternal recumbency, where they typically continue to bite or nip one another |

Dancing  | Two stallions rear, interlock the forelegs and shuffle the hindlegs while biting or threatening to bite one another’s head and neck |

Defecate over  | Defecation on top of fecal piles in a characteristic sequence: sniff feces, step forward, defecate, pivot or back up, and sniff feces again |

Erection  | Fully extended and tumescent penis. Observed during mildly and moderately aggressive encounters. Bachelors will mount one another with an erection and anal insertion has been observed |

Flehmen  | Head elevated and neck extended with the eyes rolled back, the ears rotated to the side and the upper lip everted exposing the maxillary gums and incisors. The head may roll to one side or from side to side. Typically occurs in association with olfactory investigation of feces |

Head bowing  | A repeated rhythmic flexing of the neck such that the muzzle is brought toward the point of the breast. Head bowing usually occurs synchronously between two stallions when they first approach each other head-to-head |

Head bump  | A rapid toss of the head that forcefully contacts the head and neck of another stallion. Usually the eyes remain closed and the ears point forward |

Head on neck, back or rump  | The chin or entire head rests on the dorsal surface of the neck, body or rump of another horse. This often precedes mounting |

Herding  | Combination of head threat and ears laid back with forward locomotion, apparently directing the movement of another horse. When lateral movements of the neck occur, the horse is said to be snaking |

Kneeling  | Drop to one or both knees, by one or both stallions engaged in face-to-face combat or circling with mutual biting or nipping repeatedly at the head and shoulders and knees |

Masturbation  | Erection with rhythmic drawing of the penis against the abdomen with or without pelvic thrusting. This is a solitary or group activity |

Mount  | Stallion raises his chest and forelegs onto the back of another horse (be it a mare in a breeding context or another male in a bachelor group) with the forelegs on either side. Also seen primarily in bachelor groups are prolonged partial mounts, typically with lateral rather than rear orientation and often with just one foreleg across the body of the mounted animal. In a behavior similar to the initial mount orientation movements (termed head on neck, back or rump) the forelegs will not actually rise off the ground. Mounts and partial mounts may occur sequentially or independently of one another |

Neck wrestling  | Sparring with the head and neck that may involve one or both protagonists dropping to one or both knees or raising the forelegs |

Parallel prance  | Often seen immediately prior to aggressive encounters, two stallions move forward beside one another, shoulder-to-shoulder with arched necks and heads held high and ears forward, typically in a high-stepping low cadenced trot (passage, in dressage terminology). Rhythmic snorts may accompany each stride. Solitary prancing also occurs |

Posturing  | Posturing describes a suite of pre-fight behaviors that includes head bowing, olfactory investigation, stomping, prancing, rubbing and pushing, all with neck arching and some stiffening of the entire body |

Sniff feces  | Approach and sniff a pile of feces or a fecal pile, usually as a part of a fecal pile display. Often associated with some pawing, this is almost always followed by defecating over the feces and again sniffing the pile |

The harem stallion exhibits characteristic, even ritualistic, responses to urine and feces of harem members. It is believed that olfactory characteristics of these materials inform the stallion of the reproductive status of the mares while his responses to them serve to maintain the harem. Stallions are more responsive to olfactory stimuli from conspecifics than are mares and geldings.8 Contact with urine, feces or vaginal fluids during courtship and copulation occurs and forms an important part of the mating behavior, resulting in a flehmen response by the stallion.2 Pawing, sniffing and flehmen are followed by his depositing small amounts of feces or urine on top of previously voided material.9,10 The stimuli offered by fecal material are discussed in detail in Chapters 6 and 9.

Development and maintenance of sexual behavior in free-ranging stallions

From the first weeks of life colts demonstrate mounting attempts, mainly on their dams. These attempts are rarely accompanied by pelvic thrusting. Erections have been observed in colts as young as 3 months of age but these are of minimal import to a herd since the mature stallions monopolize estrous females and, in any case, spermatozoa are not found in testes before 12 months of age. Spermatogenesis lags behind hormonal maturity. Fertility does not increase significantly until the colt is approximately 2 years old with the histological transition from the pre-pubertal to the post-pubertal stage occurring at a mean age of 27.8 months (n = 28).12

Most colts leave the natal band and join bachelor groups around the time of the birth of their siblings.13 For example, in one study of Misaki feral horses in Japan, 17 of 22 colts left their natal bands at this time.13 Scarcity of resources is also regarded as a common cause of voluntary separation.14 So, as colts become steadily bolder with age and playmates disperse, they may gravitate toward bachelor groups in search of recreation.15 Beyond the age of 3 years, remaining young males may be forced to leave the harem group during the breeding season as a result of increased aggression by the harem stallion.2,14

The behavior of young stallions can then be considered in two stages. The first is a developmental stage in which the colts that have just dispersed from the natal band (between 0.7 and 3.9 years of age in Misaki horses) engage more in social play than agonistic behavior, while the second is a pre-harem formation stage, which involves departure from the bachelor group.16 The separation of the highest-ranking stallion from the subordinate males has significant behavioral and physiological consequences.

The status of the stallion is broadly correlated with androgen activity. Testosterone concentrations increase with the age of stallions until they form their own harems.15 Furthermore, for individual stallions, testosterone concentrations are correlated with harem size.15 So, in a harem stallion, sexual and aggressive behavior, accessory sex-gland activity, testicular size and semen quality are enhanced by the dispersal of potential challengers. Meanwhile, stallions becoming bachelors undergo changes in the opposite direction3,11 and may show signs of concurrent depression (Sue McDonnell, personal communication 2002). Paradoxically, some domestic stallions may redevelop their libido when another stallion is brought to the breeding area, and some slow-breeding novice stallions seem to increase their arousal when given the opportunity to watch other stallions copulate.9

It is worth noting that despite low androgen concentrations, agonistic behavior, including mock and serious fighting, is a conspicuous characteristic of bachelor groups.11 Continued studies of bachelor groups could serve to further challenge the traditionally held view that stallions are innately aggressive and somehow deserving of isolation.17

Free-ranging matings

Prolonged pre-mating interactions are the norm for all free-ranging equids. Harem stallions discriminate among mares, according to their maturity and length of residency in the harem. As evidenced by the increased frequency of flehmen responses, olfactory stimuli help to identify estrous mares, but they are supported by visual and auditory cues from the mare.18,19 Always favoring mature harem mares, the harem stallion will often ignore young estrous mares (from both his and other harems) and actively chase away mature mares from other harems.20 Free-running stallions usually interact with sexually active mares or their excrement for many days before copulation. Often these encounters can be counted in hundreds per day.20 Because stallions can differentiate the sex of a horse on the basis of its feces (not its urine), it has been suggested that sampling of feces is extremely informative for a stallion when monitoring the cyclicity of females in his harem.10

When he has located an estrous mare, or she has located him, the harem stallion will often attract her attention by whinnying from a distance and then pawing the ground, prancing and nickering as he approaches. Once these preliminaries have taken place, the mare actively contributes to precopulatory behavior.21 To illustrate, it has been demonstrated that 88% of sexual interactions that lead to successful copulation begin with the mare approaching the stallion.20 An important trigger of the stallion’s physical sexual arousal seems to be the head-to-head approach by the mare toward him, followed by her moving forward or swinging her hips toward his head.20

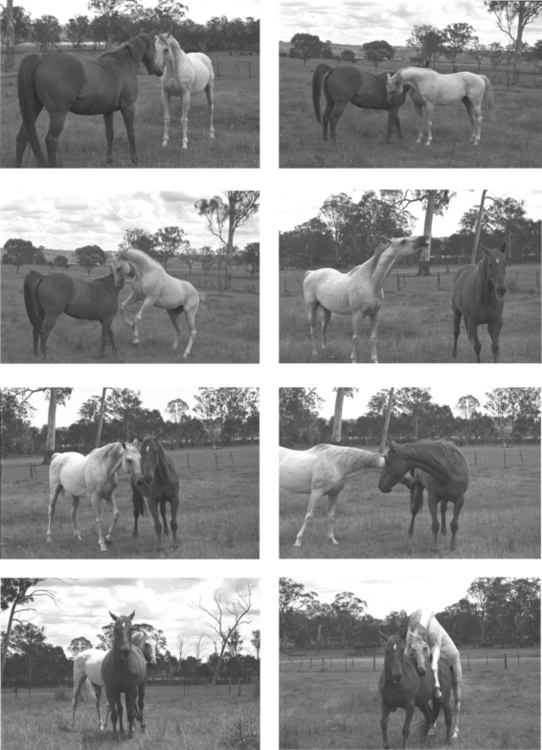

A stallion’s method of determining a mare’s receptivity is to nuzzle and push her hindquarters. Pre-copulatory behavior demonstrated by the stallion includes sniffing, nuzzling, licking and nibbling or nipping the head, shoulder, belly, flank, inguinal and perineal regions of the mare (Fig. 11.1).2,20,22 These prompts may elicit a mildly aggressive display by the mare, despite her being in full estrus. However, as this aggression subsides, the mare tolerates closer approaches by the stallion. Further arousal results when positive feedback is received from the mare.23

Figure 11.1 Courtship and copulation in the horse.

(Photographs courtesy of Michael Jervis-Chaston.)

Pre-copulatory behavior continues until the mare’s stationary ‘sawhorse’ posture cues the stallion to mount. Mounting may occur without erection. Studies have shown that mounting without an erection is common and has been demonstrated among highly fertile pasture-breeding horses.2 The number of mounts without an erection is typically 1.5–2 times the number of mounts with erection.2 In free-ranging equids, mounting with an erection almost always leads to insertion and ejaculation. While young inexperienced stallions typically mount laterally and then adjust their position, mounting by mature males is usually achieved by an approach from the rear. Although they may ejaculate sooner than their more experienced peers, colts take significantly longer to achieve an erection (after first seeing an estrous mare) and to mount.24 Once he has mounted correctly, the stallion grasps the mare’s iliac crests with his forelegs while his head leans against her neck, and he often nips or grasps her mane with his teeth.2

Free-ranging pony stallions achieve intromission during the first mount in 55% of copulations.25 Successful intromission (Fig. 11.1) during subsequent attempts is facilitated if the mare remains stationary. Intromission is generally accomplished after one or more seeking thrusts and is often marked by the stallion closely coupling up to the mare and paddling his feet as if attempting to ensure that they are on a firm surface.2 An average of seven pelvic thrusts26 occur before ejaculation, which is characteristically indicated by:

• flagging of the tail (associated with transient shrinkage of the urethral lumen and six to nine spurts of ejaculate)27

• rhythmic contractions of the muscles of the hindlegs

• an increase in respiratory rate

The period from intromission to ejaculation is usually 10–15 seconds, with young males tending to take less time.23 After ejaculation, the stallion often appears dazed as he relaxes on the mare’s back and his penis becomes flaccid. Once the stallion has regained his alertness, the mare steps forward, easing the stallion’s chest over her hindquarters, so that he lands gently on his front feet.27 The mean interval between the end of ejaculation and the start of dismount is eight seconds (Table 11.2).23

Table 11.2 Typical frequency and latency of copulatory behaviors by young and adult domestic stallions

| Typical value | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency of responses | ||

| Sniff or nuzzle | 3 | 0–80 |

| Lick | 0 | 0–20 |

| Flehmen response | 2 | 0–10 |

| Nip or bite | 0 | 0–25 |

| Kick or strike | 0 | 0–10 |

| Vocalization | 3 | 0–35 |

| Number of mounts | 1 | 1–3 |

| Number of thrusts | 7 | 2–12 |

| Latency of responses (seconds) | ||

| Time to erection | 10 | 0–500 |

| Time to first mount with erection | 15 | 10–540 |

| Time from mount to insertion | 2 | 1–5 |

| Time from intromission to first emission | 15 | 8–20 |

After Waring et al24 and McDonnell.2

The stallion’s post-copulatory behavior often includes sniffing the mare’s vulva, as well as the spilled ejaculate or urovaginal secretions of the mare, and this typically prompts the flehmen response.28 After ejaculation, the stallion and mare generally uncouple within 3–15 seconds, with the mare being first to move away in 60% of cases and the stallion in 26%, although occasionally the mare follows.25

Mares and stallions will often separate from the harem group during courtship and mating. Although the pre-copulatory interactions with mares may last several days, the copulatory interactions themselves frequently last for less than a minute. While breeding rates as high as 18 per day have been recorded,2 the daily mean for adult stallions is 11.23 The refractory period after ejaculation appears to be shorter in free-running stallions than in their intensively managed counterparts.20

Seasonality

Stallions possess an endogenous circannual reproductive cycle that is responsive to photoperiod.29 Timed to synchronize with the emergence of mares from winter anestrus, the responsiveness of stallions to sexual cues increases in spring and is maintained until the beginning of autumn but never completely disappears. The seasonality in testosterone concentrations15 is reflected in semen quality and can also influence the number of mounts per ejaculation, latency to achieve intromission, frequency of biting and striking.30 The prevalence of spontaneous erections in masturbating stallions also increases with day length.31

The artificial breeding season that starts in late winter for many breeds (such as the Thoroughbred, Standardbred, Quarterhorse and Arabian) may contribute to reports of low sexual vigor. The physiological season can be brought forward in young and middle-aged stallions by placing them under artificial lights, which can increase testicular size and sperm output.32 It is interesting to note that no deleterious effects on fertility have yet been reported in shuttle stallions that work two seasons per year by being shipped between northern and southern hemispheres.32

Traditional stallion management

The value of many stallions and the risk of injury through fighting are the principal factors that drive their owners to stable them and minimize unsupervised contact with other horses. By clipping out elements of the harem stallion’s sociosexual behavioral repertoire, hands-on stallion management can leave the entire male equid with the opportunity to perform only brief pre-copulatory interactions (Fig. 11.2).20 The resultant arousal and thwarted motivation can contribute to the handling difficulties some stallions present.

Domestic breeding stallions are generally maintained in physical isolation, either stabled alone or near other stallions.33 Breeding farms with more than one breeding stallion often stable all the stallions together, away from the mares, in a stallion yard. This management regime has the potential to impose some characteristics of the bachelor group on some occupants of the yard. McDonnell20 found that the bachelor status of stallions could be effectively reversed by housing them in a barn with mares or in a paddock adjacent to mares. Regardless of the season, libido, testosterone concentrations, testicular volume and efficiency of spermatogenesis increase once the trappings of bachelor status are removed.3

While most stallions over 20 years of age retain their libido, few maintain competitive sperm counts. The decline of this fertility parameter begins at approximately 10 years of age. Testosterone concentrations 36 hours before and after injection of human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) may help to detect declining reproductive function in aged stallions.34

Domestic stallions are generally permitted to copulate in three situations:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree