Chapter 12 Behavior of the mare

Chapter contents

Sexual maturation

The onset of puberty and reproductive activity during a filly’s first ovulatory cycle is affected by her season of birth. Spring-born fillies tend to ovulate during the late spring when they are 12–15 months old, whereas late-born fillies show surges of luteinizing hormone (LH) and progesterone that allow some (but not all) of them to display estrus and ovulate at younger ages.1 When planes of nutrition are marginal, such as in the free-ranging state, puberty may not occur until the filly’s third spring.2 Although fillies show a characteristic seasonal pattern of plasma follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and LH fluctuations even when ovariectomized, probably as a result of secretions by the adrenal cortex,3 their breeding season appears to be shorter than that of adult mares.1 In their free-ranging state, fillies usually seek contact with bachelor stallions or with unfamiliar harem stallions. When seeking sexual activity with resident, and therefore familiar harem stallions, fillies are likely to be ignored, especially if more mature mares are concurrently receptive. This allows subordinate stallions to consort with these young females and perform so-called ‘sneak matings’ (which are associated with low conception rates).

In terms of their social integration with other horses, mares can be categorized as being loyal to a single stallion, part of a multi-stallion band or social dispersers (females in transit – so-called mavericks).4 Interestingly, compared with the mares in single-stallion bands, the disperser mares have been shown to have a greater parasite burden and poorer body condition despite spending a similar amount of time feeding.4 Compared with all other mares, they also have the lowest fecundity and the greatest offspring mortality rates. A mare is thus much more likely to pass on her genes if she retains the companionship of at least one stallion. Beyond that, the stability of the mare–stallion relationship in single-stallion bands, with its resultant containment of agonistic behavior, contributes considerably to reproductive success and therefore biological fitness.4,5

Mares will regularly interfere with other mares during courtship and mating. The behavior of a mare in response to seeing another mare having contact with her stallion depends on her rank and reproductive state, being most obstructive when she is in estrus.6

In general, mares become increasingly receptive towards stallions as they age and will continue to breed until their early twenties.7

Reproductive cycles

Being seasonally polyestrus, mares show a cyclical active estrus8 (7.1 ± 4.2 days) and quiescent diestrus8 (16.3 ± 2.9 days) throughout the breeding season8 (152 ± 50 days). Season lengths become more restricted as one travels nearer the Poles.7 Of all ungulates, horses have highly variable cycle lengths9 and for this reason variations in estrous cycle are completely unreliable as a means of diagnosing ovarian dysfunction. Cycles, of which there are a mean of 7.2 ± 2.0 per year,8 vary in length and behavior, with some mares showing a shift in temperament from normally placid disposition to irritability and vice versa. More common in fillies than in mares, protracted estrous periods of up to 50 days have been reported,10 while their contraction as a result of veterinary examinations per rectum has also been noted.11

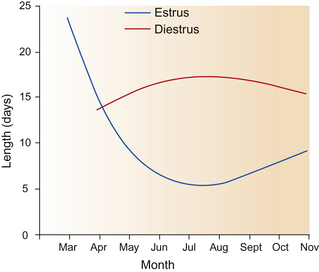

The duration of estrus decreases at the height of the breeding season (Fig. 12.1), the trend being matched by reciprocal increases in diestrus duration that keep the length of the whole cycle relatively constant.

Figure 12.1 Variation of estrus and diestrus duration during the northern hemisphere breeding season.

Mares reject advances by stallions and show relative disinterest in their company during diestrus and during periods of rising and high plasma progesterone concentrations.12 A diestrous mare approached by a stallion becomes restless, switching her tail and flattening her ears as she threatens to kick, strike or bite (Fig. 12.2). Because behavioral responses associated with estrus may persist to varying extents in mares in anestrus,13,14 it is important for stud personnel to take repeated measures of responses to teasing so that changes in frequency of responses, rather than the presence or absence of responses, can be monitored.

Even when a mare is receptive, squealing and strike threats may occur as a preliminary part of the nasal contact phase of a successful sexual encounter. Estrus in the mare is characterized by courtship behaviors such as abrupt halts during locomotion, approaching and following stallions, lifting the tail (before being mounted or after being mounted), clitoral winking (Fig. 12.3) especially during teasing, urinating (up to 21 urinations in an hour have been recorded15), and tolerance of the stallion’s pre-copulatory behavior such as sniffing and nibbling. Depending to some extent on individual differences between mares, receptivity peaks 1–3 days prior to ovulation (although this has been disputed16). Above all, estrus in the mare is defined by her standing firmly with her tail up while being mounted.13 Ovulation typically occurs 36 hours before the end of estrus and is marked by the decline in the mare’s receptivity.

Estrous mares frequently follow and place themselves in the vicinity of a stallion, especially if contact with him is intermittent.6,17 If their solicitations are ignored, mares may display the estrous stance nearby periodically or, if this fails to attract the attentions of the harem stallion, they may even disperse in search of other males. Occasional mares exhibit signs of colic during estrus to the extent that they are presented for bilateral ovariectomy.18,19 There are also occasional instances of estrous mares mounting or being mounted by other mares.2 Strangely, in Icelandic mares, this response is regarded as normal even when a stallion is present and is used by stud managers as an indication of early estrus. The estrous mares are almost always mounted, while the mounting is most usually performed by pregnant mares (Machteld van Dierendonck, personal communication 2002).

While prolonged tail-raising, the urination-like stance and clitoral winking in combination with the increased vascularity of the vaginal mucosae seem to provide strong visual attractants for stallions, facial expressions in estrous mares have also been noted. Open mouths and bared teeth are common in the females of wild asses that adopt forced mating styles. Called ‘Rossigkeitsgesicht’ in zebras (Fig. 12.4), this accompanies the characteristic urination stance to contribute to the composite attractive signal to stallions.20 The response is also seen in occasional mares,21 with Standardbreds more likely to demonstrate it than Arabians.22 Likened to the snapping response of juveniles in the presence of a threat, this response is interpreted by some observers as a sign of submission2 or conflict21 while others have demonstrated that it can elicit aggression from observing horses.23

Although pony mares have been described anecdotally as having more distinct ovulatory and anovulatory behaviors,2 other data suggest that cold-blooded mares are more likely to have silent estrus than other breeds.24 Meanwhile, reduced antagonism to teasing when not in estrus and generally subdued manifestations of estrus are also reported in association with compromised thyroid function.25 The average interval between the first signs of estrus and ovulation is 5.16 ± 2.65 days.26

Although they are irregular, estrous cycles are common in mules and the extent to which these hybrids are functionally infertile varies considerably.27 Mules often have follicles that ovulate and luteinize but they generally lack oocytes (Lee Morris, personal communication 2002). That said, they do very occasionally bear live foals.28

The importance of auditory perception in eliciting typical estrous responses has been highlighted by studies of the relative effects on mares of audio recordings of the characteristic stallion nicker versus the presence of a stallion.29 In response to these recordings, estrous mares, especially barren ones, showed overt estrous behavior including tail-raising, clitoral winking and abduction of the hindlegs. Maidens and mares with foals at foot exhibited some of these reactions but at a lower frequency. There are reports of reasonable efficiency in detecting estrus in mares by playing back recordings of stallion vocalization with and without added stallion scent. That said, for this to be a useful part of stud management in the absence of a stallion or teaser, a minimal schedule of three times weekly would be required. In a four-week study of 11 mares estrus was detected with the stallion auditory and olfactory stimuli method, on average more than four days before 80% of ovulations.30 Although the usefulness of stallion vocalization recordings used in isolation in estrus detection has been contested,31 when used in combination with palpation of the inguinal region of mares this approach was reported to be 97% accurate.32

During copulation the mare adopts a characteristic base-wide stance that helps her to balance. Although her neck is usually lowered, she remains very alert with her ears upright. She may look round slightly to monitor the stallion, especially during ejaculation.15 Dismounting is often assisted by the mare moving forward.32 The couple remain reasonably close to one another after copulation and the mare continues to raise her tail and urinate until grazing and social interactions with others take priority.33 In the free-ranging state, matings will occur approximately six times per heat in single-stallion groups.34 It is important that we recognize the many ways in which hand-breeding can so easily compromise a mare’s ability to behave normally during courtship and copulation (Fig. 12.5).

Artificial influences on the breeding season

It is broadly accepted that the breeding season imposed by humans on horses, most notably Thoroughbreds, is artificial and does not entirely coincide with most mares’ maximal reproductive efficiency.35 As a result, sexual receptivity without ovulation occurs during the early stages of the artificially advanced breeding season. The use of lights (not to mention GnRH, allyltrenobolone or progesterone) to induce ovarian cycling is now commonplace and reasonably sophisticated but it necessitates stabling and therefore may have deleterious effects on the social needs of mares. The imposition of artificial social groups is likely to have an effect on behavior since herd size is known to affect reproductive efficiency.6

The primary advantage of bringing mares into stables for exposure to 16 hours of artificial lighting is that it advances the onset of cyclicity early in the breeding season. In addition it facilitates supplementary feeding. Insufficient or inconsistent planes of nutrition may compromise sexual behavior and ovarian activity.8,36,37

It has been noted that a higher percentage of non-palpated mares conceive earlier in the breeding season compared with palpated mares,11 but it is not clear whether a causal relationship exists or whether mares are more likely to be palpated because they are more likely to be failing to show behavioral manifestations of estrus. Follicular immaturity leading to behavioral estrus without ovulation (so-called ‘spring estrus’), an ovarian dysfunction diagnosed in as many as 40% of infertile mares, is one of the most common causes of infertility in the horse and has been associated with unsatisfactory nutrition or management.9 The most common cause of infertility is pregnancy loss.38

The length of estrous periods in a managed context is longer than in the free-ranging state, apparently because of the psychic effect of the separation of mares and stallions.9 Data on herd mating activities suggest that stallions are twice as active sexually during 0600–0800 and 1600–1800 hours than during 1800–0600 and 0800–1600 hours.39 Perhaps, as efforts are made to reduce the effects on horses of intensive management, the times of day at which stallions and mares are joined for breeding purposes should be brought into line with these times of peak natural activity.

While transportation induces hormonal and ascorbic acid responses indicative of stress,40 it does not alter estrous behavior, ovulation, duration of the estrous cycle, pregnancy rate or pre-ovulatory surges of estradiol and LH.41 Artificial influences on fertility also include attempts at birth control, most notably in feral populations. Single inoculations with microspheres of porcine zona pellucida vaccine have reduced feral mares’ reproductive rate to approximately 11%, a finding that offers some support for alternatives to culling.42

Foal heats

Characterized by their intensity as well as their association with diarrhea in the foal, foal heats occur on average 8 days after parturition43 as a result of a decline in the blood progesterone/estradiol concentration ratio that begins at the time of parturition, and an initial surge followed by pulsatile releases of LH post-partum.44 While free-ranging mares have been observed mating within hours of foaling,2 most ovulate between 4 and 18 days post-partum. Similarly, mares display estrus 2–6 days after injections of exogenous prostaglandins (5 mg PGF2α, i.m.), given to induce abortions.45 Daily progesterone injections have been used to delay the onset of foal heats.46 Meanwhile, the beta-blocker propanolol has been reported to increase the exhibition of foal heat and the pregnancy rate at this heat. The mechanism for this effect is thought to involve increased myometrial motility and enhanced uterine involution.47

Silent heats

It is recognized that ovulation may occasionally occur without behavioral heat.9 Approximately 6% of ovulations occur without overt signs of estrus.8 Some mares are predisposed to such silent heats (also known as sub-estrus) without any disruption of their cyclicity. The role of social rank in mares’ behavior at estrus is not as clear as that of cattle, but it appears that high-ranking mares may bully subordinates when in estrus. Mares that show no sign of cycling (see the case study at the end of this chapter) should have their diets investigated as part of a full clinical work-up that includes gynecological and endocrinological investigations.

Split heats

When a mare exhibits behavioral estrus that is transiently interrupted by an uncharacteristically brief period of quiescence, she is said to have had a split heat. This phenomenon occurs with reasonable frequency (12% of ovulations8) and as such justifies at least daily teasing in commercial breeding operations. Meanwhile, the appearance of a prolonged estrus may arise in oliguric mares secondary to irritation caused by the persistent presence of urine.2

Anestrus

In late autumn and winter, most (but not all) mares become sexually dormant and are said to have entered anestrus (214 ± 50 days8). Entry into anestrus can be considered complete if a mare does not exhibit cyclic estrous behavior, has no follicles with a diameter of 25 mm or larger, and has progesterone at concentrations of 1 ng/mL for at least 39 days.48 The transition into the breeding season occurs once a threshold in LH concentration within the anterior hypothalamus is reached.49 Meanwhile, the onset of individual estrous cycles may be delayed by psychological influences over behavioral activity, spontaneously persistent luteal function, endometritis and granulosa cell tumors.34

The influence of hormones and exogenous factors on reproductive behavior

Hormonal control of ovulation can be achieved by using exogenous steroids with or without prostaglandins.50 Estrous displays can be induced by administering exogenous steroids.50 For example, estradiol elicits soliciting behavior within 4 hours of injection, while progesterone usually results in the absence of sexual behavior.3,51 Altrenogest can be given orally to regulate estrous behavior early in the year, and its withdrawal will synchronize estrus in cycling mares and those previously exposed to artificial light.52 Conversely it has been suggested that endometrial edema as appreciated by ultrasonography may indicate the optimal time for coitus and provide an instant indication that the basal concentration of progesterone is <1 mg/mL.53 But estrus is not purely a product of hormonal flux, since estrous behavior reflects a combination of other factors, including the presence of a stallion, social rank and duration of teasing. For example, when mares are stimulated by restrained teasers, their estrous display lengthens.9 Similarly, failure of estrus can often be due to the absence of exogenous factors such as odors, sounds, sight and touch9, e.g. that arise with appropriate attention from stallions.

Pregnancy

The gestation period of the mare is approximately 11 months or 340 days, with generally slightly shorter periods in smaller breeds.54 Gestation duration in a large study of Australian Thoroughbreds55 (n = 522) ranged from 315 to 387 days (mean 342.3 days). The survival rate of Thoroughbred foals delivered at less than 320 days of gestation is approximately 5%.56

Factors that influence the duration of a mare’s gestation include her plane of nutrition towards the end of her pregnancy and the sex of the foal. Howell & Rollins57 found that mares on higher planes of nutrition tend to foal earlier than those on maintenance diets. In the free-ranging state, mares normally foal in mid to late spring, a strategy that usually ensures sufficient feed being available for lactation. By showing that foals conceived in early spring had longer gestations than those conceived in mid to late spring, Hintz et al58 confirmed the importance of seasonal effects on the biological fitness of foals (a similar trend was reported by Campitelli et al59). The sex of the foal contributes to the duration of gestation, in that fillies are generally born 1–2 days before colts.55 Mares lose more condition prenatally when carrying a colt if they were originally in good condition at the time of conception, but more when carrying a filly if they were in poor condition.60

While some mares become actively aggressive to approaching stallions during pregnancy, others may remain friendly61 and raise the suspicion that they are returning to estrus. After between 40 and 70 days of pregnancy, follicles are produced in response to eCG.62 They are generally large in size and remain active, ovulating to form accessory corpora lutea. Estrogen produced from these follicles is thought to prompt some pregnant mares to consort with stallions and exhibit some estrous behavior during the first trimester of pregnancy. The response occurs more frequently in mares bearing female foals than in those bearing males.63 Up to 35% of ovariectomized mares,18 and also mares in an anovulatory period, show sexual responsiveness.1,3 This suggests that mares’ ability to dissociate sexual behavior from ovulation may persist even when they are pregnant. However, these manifestations (which may occur a mean 1.76 times per pregnancy39) often lack the usual potency associated with ovulation. Asa17 suggests that non-reproductive sex may serve to influence stallions to remain with their bands during the non-breeding season.

Asa et al62 examined the effect of adding a stallion to an established group of 12 pregnant pony mares. After the experimental introduction of stallions into random harem groups, full estrous behavior was not observed. Instead, only weak signs of estrus were noted, with only four mountings recorded and only a single tail raised. Social interactions such as grooming between the mares increased, while the only approach between mares and the stallion was an initial ritual greeting early on in each exposure.

Foaling

Although the behavior of the mare does not change markedly in the months leading to parturition, significant differences arise immediately before foaling.2,62 Shaw et al64 examined mare behavior 2 weeks prior to parturition. A total of 52 pregnant mares in box stalls were observed at 30-minute intervals between 1800 hours and 0600 hours. In the 2 weeks before foaling, mares spent 66.8% of their time standing, 27% eating, 4.9% lying in sternal recumbency, 1% lying in lateral recumbency and only 0.3% walking. Challenging the notion that the mare reduces her ingestive activities immediately prior to parturition,9,61 eating was the only behavior unaffected by the imminent foaling. On the night of foaling, mares spent less time standing (53.3%) and more time in sternal (8%) and lateral (5.3%) recumbency and walking (5.3%).64 This reflects the restlessness of mares when they are about to foal and the fact that they almost always choose to foal in a recumbent position (a characteristic that led to the development of foaling belts that can detect recumbency).

In their free-ranging state, mares about to foal often become parted from the herd either by seeking relative isolation (sometimes accompanied by older offspring or another adult mare) or by being left behind. Along with the other peri-parturient behaviors, this strategy provides a nurturing environment for the foal and helps to avoid mis-mothering, in accordance with the ‘binding theory’ offered by Klingel.65 Average time spent walking tends to increase on the day of birth (most notably the 30 minutes prior to parturition), with higher-ranking mares tending to try to separate themselves furthest from the herd, and maiden mares remaining reasonably close.66,67 Mares confined in a box stall, on the other hand, may be required to foal within auditory, olfactory and visual contact of other mares. They are often described as being alert, uneasy and restless before parturition.9 This may be due, at least in part, to their motivation to separate themselves by locomotion being thwarted. While physiological changes include swollen teats, distended udder and softening of the cervix, behavior changes may also include swinging and rubbing the tail against fixed objects as the vulva becomes relatively flaccid.61

It seems that regardless of the bond they may have with particular personnel, most mares prefer not to foal in the presence of humans and, perhaps in a bid to ensure isolation, may delay foaling by prolonging the initial stage of parturition.2,64 When left undisturbed, most mares foal at night (e.g. in Shaw et al’s study64 86% foaled between 1800 and 0600 hours), presumably as a means of avoiding daytime predators. Fraser9 proposes that colts are born later in the night than fillies and rather unconvincingly suggests that this is for the ‘good of the species’ since fewer males are required for reproductive success of a group. There is evidence that the percentage of night births is higher in spring than in winter59 although others report that seasonal daylength and onset of darkness have no effect on the mean time of foaling.68

Continual disturbance, especially at night may adversely delay the onset of foaling.68 On many studs, laudable attempts to minimize human interference and reduce imposing unnatural delays include using one-way mirrors and video surveillance equipment. However, the avoidance response seen in most mares during foaling is by no means universal. Some mares even appear to seek human company at this time.61 It would be interesting to see how attempts to ‘imprint’ fillies (see Ch. 4) affect their responses to humans when peri-parturient.

Immediately prior to parturition the mare’s behavior increasingly involves stretching, yawning, repeated recumbency and standing, walking, tail-swishing, kicking, looking at flanks, pawing at the ground, crouching, straddling and kneeling. These responses all imply that she is undergoing abdominal discomfort9 that may last from a few minutes to hours.2 Patchy sweating on the flanks and girth area indicates that first-stage labor is about to commence. This and persistent raising of the tail seen at this stage gave rise to the emergence of parturition detectors (e.g. as described by Bueno et al69).

Depending on their force and timing, contractions induce different responses in the mare.61 With modest contractions she may swish her tail or stamp a hindleg. Larger, more powerful contractions cause her to become transiently tucked up in the flank or to lift her tail over her back and lean backwards onto her hindlegs.

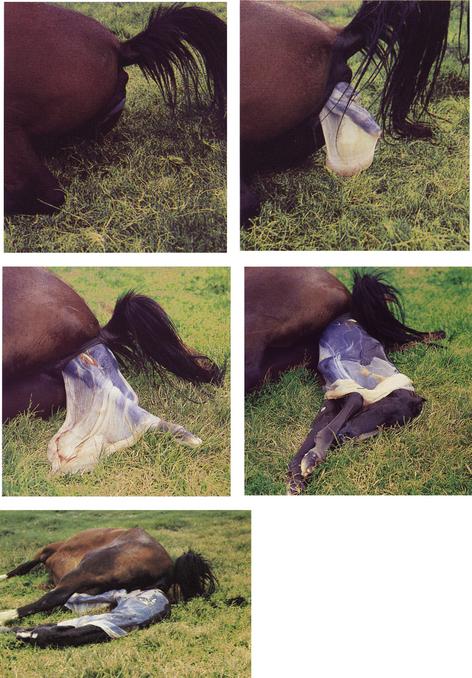

Usually, when the placenta ruptures and the allantoic fluid escapes, indicating the second stage of parturition, the mare lies down (a response often accompanied by the greatest passage of fluid) in preparation for forceful and repeated straining. Some mares may investigate the fluid and consequently exhibit flehmen and occasionally nicker.10 Sternal recumbency is commonly adopted but it is not unusual for the mare to stand and reposition herself repeatedly, especially if she is disturbed.70 Vigorous rolling is also reasonably common and is thought to represent attempts to correctly position the foal. The foal’s forelegs either side of or to one side of its head engage in the vagina, then may emerge from the vulva covered by a veil of amniotic membrane (Fig. 12.6).

Straining efforts, numbering between 60 and 100 (n = 5), are required especially to expel the foal’s forequarters and head.70 Data from Thoroughbreds suggest that compared with experienced brood mares, maidens spend slightly longer in second-stage labor (mean of 21 minutes for primiparae versus the mean of 18 for experienced mares71), while pony mares take an average of 12 minutes.72 Foals from primiparous mares are considered to be at high risk of thoracic trauma.73 The final expulsion is usually achieved with the mare in lateral recumbency with legs extended. Expulsive efforts may cause the mare’s upper hindlimb to become raised. With the emergence of the foal’s head, forelimbs and hips, the second stage of parturition is complete. Unless disturbed, the mare then usually remains in lateral recumbency, often with the foal’s hindlimbs still in the vagina.

The third and final stage of parturition involves the transfusion of blood from the placenta to the foal during the post-partum pause and the passage of the placenta.9 If parturition occurs without difficulty then, after the post-partum pause which allows blood to leave the placenta and reach the foal,74 the foal will free itself of fetal membranes by raising its head and will sever the umbilical cord as it moves away from the mare.

Third-stage labor is marked by signs of abdominal discomfort, including looking at the flanks, sweating and pawing – behaviors that seem to have a stimulating effect on many observing neonates. Approximately 1 hour after delivery of the foal, the placenta is expelled, often as the mare rises from a bout of rolling. Mares typically show some olfactory investigation of the membranes, which elicit flehmen responses and occasionally some perfunctory nibbling. In the free-ranging state, the mare and foal leave the site of foaling soon after the placenta is discharged. This is thought to contribute to biological fitness by avoiding predators that may be attracted by the odors of the fluids and membranes passed during parturition. It also marks the mare’s return to the relative safety of her herd, which may be seen moving towards the fresh dyad to investigate. High-ranking mares have been observed to take longer to rejoin their affiliates than subordinates.66

Mare–foal interactions

The mother–infant bond

Interactions between the mare and her newborn foal enhance the bond between them and contribute to biological fitness by facilitating the survival and full development of the foal. Bonding in the first few days is critical to the foal’s survival because this is when mortality is highest.75,76 The mare–foal bond seems to grow at the expense of the bond between the mare and her herd affiliates.77 Indeed new dams put a distance between themselves and other adults, perhaps to reduce outside interference in the bonds they are forming with their offspring.77 It is interesting to note that the attachment between primiparous mares and their male offspring (as estimated by the number of times colts return to their natal bands after dispersal) is significantly stronger than dam–filly combinations.78

Contact with the mare and urination along with various other behaviors listed in Tables 7.1. and 7.2 have been used to score foal health so that veterinary attention can be requested for those showing subnormal development or viability.79 In addition the mean times taken by Thoroughbred foals80 (n = 390) to perform key behaviors are shown in Table 12.1.

Table 12.1 The mean times taken by thoroughbred foals (n = 390) to perform key behaviors80

| Behavior | Mean time after parturition (minutes) |

|---|---|

| Umbilical cord rupture | 6.2 |

| Suckling reflex | 36 |

| Standing | 49a |

| First suckling | 94b |

| Elimination of the meconium | 127 |

a All foals stood up within 2 hours 23 minutes of parturition.80

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree