chapter 20 Avian and Exotic Radiography

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

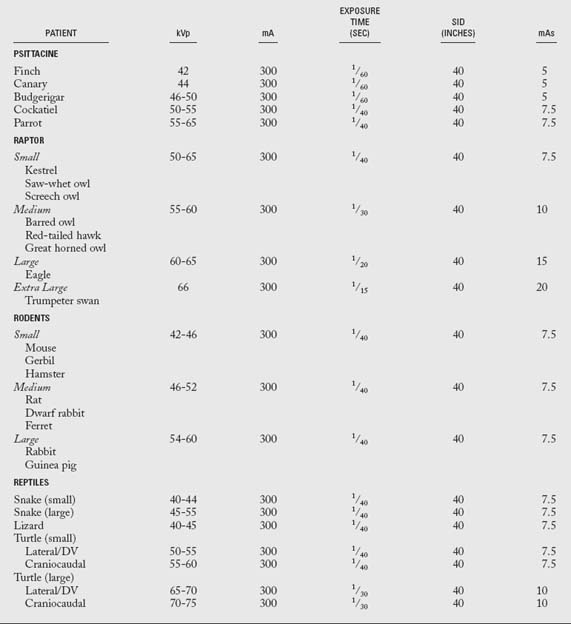

Exposure Factors

The exposure factors listed in Table 20-1 can be used for an ultradetail rare-earth screen/medium (par)-speed film system. If a Plexiglas sheet is used for avian radiography, add 2 to 4kVp to the exposure factors listed.

Patient Restraint

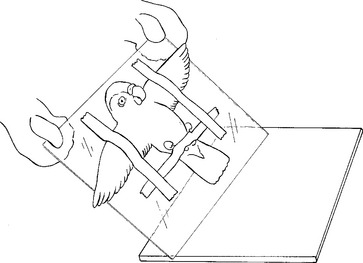

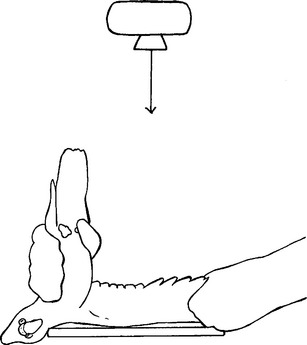

Physical restraint involves such devices as a Plexiglas sheet, ropes, sandbags, and radiolucent adhesive tape. Birds can be restrained directly on a cassette; however, it is recommended that they be positioned on an intermediate surface, especially if several views of the same projection are scheduled. A thin radiolucent sheet of Plexiglas slightly larger than the cassette often serves as an intermediate surface. The avian patient can be placed in position and secured with tape on the radiolucent sheet, which can then be placed directly on the cassette (Fig. 20-1). The type of tape used for physical restraint is important. Scotch tape and cloth medical tape should be avoided because they can damage or remove feathers, fur, or scales.

Plexiglas tubes have been used for the restraint of rodents and other laboratory animals. However, this method is not ideal for radiography because it is difficult to position a patient accurately in a tube. For example, it is not practical to expect a diagnostic radiograph of a rodent thorax if the front limbs are superimposed over the thoracic cavity.

Both manual and physical restraint methods have limitations. Physical restraint may result in excessive patient stress and possible injury from struggling. Injectable sedatives and inhalant anesthetics have greatly increased the feasibility and safety of radiographic procedures involving birds and exotic animals; in fact, they have become the safest methods in use. Chemical restraint is most often used in combination with other positioning techniques to obtain a properly positioned radiograph.

Whole-Body Ventrodorsal View

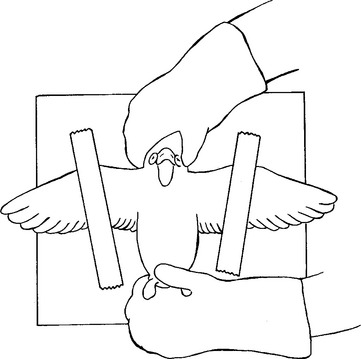

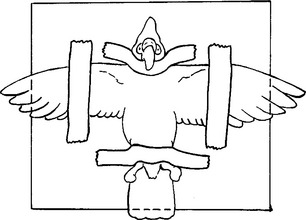

The avian patient is positioned on its back so that the sternum is superimposed over the spine. The wings are extended laterally and secured. If manual restraint is used, one hand grasps the head from the back, holding the mandibular articulation between the thumb and the forefinger. The other hand takes the feet and carefully extends them caudally. The wings should be abducted slightly from the body and held down by adhesive tape (Fig. 20-2).

Physical restraint for avian radiography is preferred. The patient is placed in dorsal recumbency as described, except that the head is secured with adhesive tape. The neck is gently extended in a cranial direction and secured to the cassette with adhesive tape (Figs. 20-3 and 20-4). Care must be taken that the airway is not compromised by the tape across the neck region. The wings are abducted laterally and taped to the cassette in full extension. The legs are extended caudally, positioned symmetrically, and fastened to the cassette with masking tape. The tip of the tail can be secured to the cassette to provide additional restraint, if necessary.

Figure 20-3 Correct physical restraint and positioning for the ventrodorsal view of the entire body of a bird.

Whole-Body Lateral View

The patient is placed in lateral recumbency, and the neck is secured to the cassette with masking tape. (NOTE: Right lateral views are taken to maintain consistency with comparable anatomic reference material.) The wings are extended dorsally directly above the body of the patient. The wing that is down on the cassette is positioned cranial to the other wing, and both are secured with adhesive tape (Figs. 20-5 and 20-6). The legs are extended ventrally away from the body wall and fastened with tape. The dependent leg is positioned cranial to the other leg. The limb closest to the cassette is always cranial to the contralateral limb so that each limb is identifiable on a lateral radiograph. The tail and body of the patient can be secured with tape if additional restraint is necessary.

BEAM CENTER: Over middle of body between spine and sternum at level of caudal tip of sternum

Wing-Caudocranial View

Manual positioning is necessary for the caudocranial view of the wing because of the awkward position required of the patient. Lead gloves are worn, and the bird is held upside down so that the body is perpendicular to the cassette. The tip of the wing feathers is held gently, and the wing of interest is extended away from the body. The cranial edge of the wing is placed on the cassette. In order for the edge of the wing to be in contact with the cassette, it is helpful to allow the head of the patient to hang over the edge of the cassette (Fig. 20-7). Exposure factors required for this view are approximately the same as those required for the entire body.

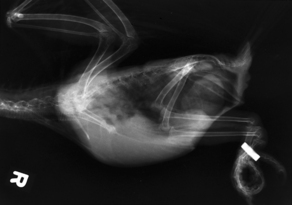

Gastrointestinal Contrast Study

A contrast study of the gastrointestinal tract can be valuable to the avian practitioner. Because visualization of many abnormalities on routine survey radiographs is difficult, the use of contrast media can be helpful in defining the location and size of a lesion. For example, because birds love to chew, they often suffer from gastrointestinal foreign bodies. In addition, stasis of the gastrointestinal tract is a common consequence when a bird is ill. Without the use of contrast media, diagnosis of such problems may be difficult or impossible.