Chapter 13 Assessment of Acute-Onset, Severe Lameness

Assessment

Medical History

Shoulder and Chest

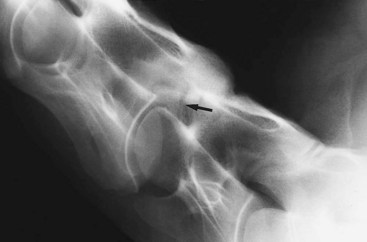

Injuries to the shoulder region usually result from a fall or collision, which may result in severe bruising only or a fracture. A fracture of the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula results in severe lameness (Figure 13-1). Slight soft tissue swelling may develop, usually without audible or palpable crepitus, and pain on palpation may be difficult to differentiate from that caused by severe bruising alone. Articular fractures of the scapula may be associated with audible crepitus on manipulation of the limb. Fractures of the body of the scapula or the humerus are usually associated with severe lameness, soft tissue swelling, and pain in that area.

After collision with a fixed object, or occasionally a fall, the scapulohumeral joint may become luxated or subluxated, with or without a fracture of the glenoid cavity of the scapula. The horse bears weight on the limb reluctantly, soft tissue swelling develops rapidly, and the distal aspect of the scapular spine may become more difficult to palpate. The limb may appear straighter than usual. A collision also may result in collateral instability of the shoulder, so-called shoulder slip, usually caused by trauma to nerves of the brachial plexus. The horse may have pain-related lameness because of bruising, together with mechanical lameness caused by neurological dysfunction (Figure 13-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree