Chapter 72 Asian Wild Horse Reintroduction Program

The first documentation of Przewalski’s-type wild horses dates from more than 20,000 years ago. Rock engravings, paintings, and decorated tools dating from 20,000 to 9,000 bc were discovered in European caves. Historically, wild horses (Equus ferus) ranged from Western Europe over the Russian Steppes east to Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and northern China.1 The first written accounts of Przewalski’s horse (Equus ferus przewalskii) were recorded by the Tibetan monk Bodowa around 900 ad. In the Secret History of the Mongols, there is a reference to wild horses that caused Chinggis Khaan’s horse to rear up and throw him to the ground in 1226. Przewalski’s horse is still absent from Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae (1758) and remained essentially unknown in the West until John Bell, a Scottish doctor in the service of Tsar Peter the Great in 1719 to 1722, observed the species within the area of 85 to 97 degrees E and 43 to 50 degrees N (present-day Chinese-Mongolian border).9 Subsequently, Colonel Nikolai Mikailovich Przewalski (1839-1888), a renowned explorer, obtained the skull and hide of a horse shot some 80 km north of Gutschen on the Chinese-Russian border. These were examined at the Zoological Museum of the Academy of Science in St. Petersburg by Poliakov, who concluded that they were from a wild horse, and he gave it the official name of Equus przewalskii (Poliakov, 1881). Present-day taxonomy places the Przewalski’s horse as a subspecies of Equus ferus.2

The last wild population of Przewalski’s Horses, called takhi in Mongolian, survived until recently in southwestern Mongolia and adjacent China in the provinces of Gansu, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia. The last recorded sightings of Przewalski’s horse in the wild occurred in the late 1960s north of the Tachiin Shaar Nuruu in the Dzungarian Gobi in southwestern Mongolia.12 Thereafter, no more wild horses were observed and the species was declared “extinct in the wild.” The reasons for the extinction of Przewalski’s horse were seen in the combined effects of pasture competition with livestock and overhunting. The species initially only survived because of captive breeding based on 13 founder animals.17 Subsequent to the establishment of the International Przewalski’s horse studbook at the Prague Zoo in the Czech Republic in 1959, the North American Breeders Group in the 1970s (which became the Species Survival Plan for the Przewalski’s Horse), and the initiation of a European Endangered Species Programme (EEP) in 1986 under the auspices of the Cologne Zoo in Germany, the captive population grew to over 1000 individuals by the mid-1980s. In the early 1990s, reintroduction efforts started simultaneously in Mongolia, China, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine. However, Mongolia is currently the only country in which true wild populations exist within their historic range.1 Reintroductions in Mongolia began in the Gobi Desert around Takhiin Tal in the Great Gobi B Strictly Protected Area (9000 km2) and in the mountain steppes of Hustai National Park (570 km2) in 1992. A third potential reintroduction site, Khomiin Tal (2500 km2), in the Great Lakes Depression, was established in 2004 as a buffer zone to the Khar Us Nuur National Park.

With the free-ranging population growing in Mongolia, the species was reassessed in 2008. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) criteria,3 the population is currently estimated to consist of fewer than 50 mature individuals free-living in the wild for the past 5 years. Because the effective population size is still very small, Przewalski’s horse is today listed as critically endangered.1

Takhiin Tal Reintroduction Project

In 1975, the Mongolian portion of the Dzungarian Gobi was established as part B of the Great Gobi Strictly Protected Area (SPA). The area was declared a United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)–Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB) Biosphere Reserve in 1990. The Great Gobi B SPA encompasses approximately 9000 km2 of desert steppes and semideserts. Herder camps are allowed at preestablished locations in the surrounding zone. They are used by approximately 100 families with almost 60,000 livestock, predominantly during winter and spring and fall migration. In summer, human presence in the park is almost negligible and traffic is less than five vehicles/week. No paved roads exist and dirt tracks are not maintained. In winter, access and mobility within the park are often limited by snow cover. Poaching occurs but, based on the small number of wildlife carcasses encountered, seems to be of minor importance compared with that in other Gobi areas.7,8

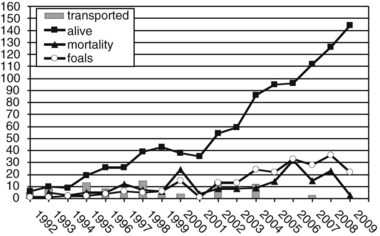

With Mongolia’s independence, a private fund and the Mongolian Society for the Conservation of Rare Animals initiated the Takhiin Tal project with the support of various international sponsors.8,20 In 1992, the first group of captive-born Przewalski’s horses was airlifted to Takhiin Tal. In 1997, the first harem group was released into the wild from the adaptation enclosures and, in 1999, the first foals were successfully raised in the wild (Fig. 72-1).11

International criticism and recommendations resulted in the establishment of the International Takhi Group (ITG; www.savethewildhorse.org) in 1999 with the goal of continuing and extending the Takhiin Tal project in accordance with the IUCN reintroduction guidelines.14 Today, the Takhiin Tal project has received international recognition and, although it is still too early to judge whether the project is a success or failure, the positive trend of the free-ranging Przewalski’s horse population is encouraging (Fig. 72-2). However, the population is still very small and is vulnerable to extinction subsequent to catastrophic environmental events, as witnessed in the winter of 2000 to 2001. At the time of this writing, southwestern Mongolia is experiencing a white dzud, a multifactorial natural disaster consisting of a summer drought with inadequate pasture followed by very heavy winter snowfall, winds, and lower than normal temperatures. Although continuing bad weather has not allowed for comprehensive evaluation, the losses to the Przewalski’s horse population in the Great Gobi B SPA appear to be massive. This situation clearly indicates the fragility of small populations to stochastic events in general, and specifically it emphasizes that the Gobi areas provide an edge, rather than an optimal habitat, for Przewalski’s horses. Subsequently, only small and isolated pockets of suitable habitat remain as future habitat for Przewalski’s horse.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree