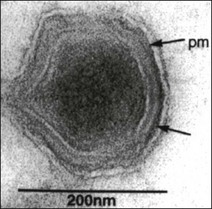

Chapter 50 African swine fever virus was formerly assigned to the family Iridoviridae. Subsequently, the virus was listed as the only member of a floating genus termed ‘African swine fever-like viruses’. Taxonomic changes have resulted in the creation of a new family Asfarviridae with a single genus Asfivirus. African swine fever virus is the type species of this genus. The virus shares a number of similarities in genome structure and replication strategy with poxviruses but differs substantially in morphology and other properties. Virions are 175–215 nm in diameter. They consist of a membrane-bound nucleoprotein core within an icosahedral capsid and surrounded by an outer lipid-containing envelope (Fig. 50.1). They are complex viruses containing over 50 proteins including a large number of structural proteins and several virus-encoded enzymes required for transcription and post-translational modification of mRNA. The genome is a single molecule of linear, double-stranded DNA. Replication occurs in the cytoplasm of host cells with release by budding through the plasma membrane or by cell destruction. African swine fever virus is stable in the environment at 20°C or 4°C and over a wide pH range, permitting the virus to persist for weeks or months in meat. Infectivity is destroyed by heating, lipid solvents and certain disinfectants such as the para-phenylphenolic disinfectants. Figure 50.1 Cryosection negative contrast electron micrograph of African swine fever virus particle. The arrows indicate the membrane components of the virus; pm = plasma membrane. Reprinted with permission: Fauquet, C.M., et al. (Eds.), 2005. Virus Taxonomy Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier Academic Press, p. 135. African swine fever is an economically important viral haemorrhagic disease of pigs characterized by fever, haemorrhages in the reticuloendothelial system and a high mortality rate. It occurs over large areas of Africa and in Sardinia and Madagascar. Outbreaks have occurred in Belgium, Italy, Malta, Brazil and the West Indies. The disease was successfully cleared from the Iberian Peninsula in 1995, almost 30 years after its introduction. Sequencing of the gene encoding the major capsid protein p72 has led to the identification of 22 genotypes. Genotyping has proven useful in determining the source of an outbreak in Georgia in 2007 (Rowlands et al. 2008). Pigs are the only domesticated species susceptible to infection. Wild boars are also susceptible. Isolates vary in virulence, producing clinical disease ranging from peracute to chronic and apparently healthy carriers. In Africa ASFV is maintained in a sylvatic cycle involving inapparent infection of warthogs, bush pigs and soft ticks of the genus Ornithodoros. Following infection young warthogs develop viraemia sufficient to infect feeding ticks. Older warthogs are rarely viraemic despite being persistently infected. Replication of the virus occurs in the ticks with both transovarial and transstadial transmission occurring. Soft ticks feed quickly on their host before returning to cracks in the ground, in walls and in burrows. The presence of infection in ticks in a given region renders the eradication of ASF much more difficult. The principal tick species involved are O. porcinus porcinus (O. moubata) in Africa and O. erraticus in Spain and Portugal (Kleiboeker et al. 1998). Ingestion of uncooked meat from infected pigs or warthogs can result in transmission. The feeding of scraps to pigs is an important mechanism of international spread of the infection with outbreaks arising close to airports or harbours. Once established in domesticated pigs transmission can occur by direct contact usually via oral or nasal secretions. The incubation period varies from four to 19 days but is typically five to seven days in acute cases. Infection in domestic pigs is usually acquired via the oronasal route. The virus replicates initially in the pharyngeal mucous membrane and tonsils before spreading to the draining lymph nodes. Infection then extends via the bloodstream to the target organs which include lymph nodes, bone marrow, spleen, lung, liver and kidney. These are the main sites of secondary replication, which gives rise to a prolonged viraemia. The virus replicates primarily in the cells of the lymphoreticular system, particularly cells of the mononuclear phagocyte system, but also infects megakaryocytes, endothelial cells, kidney cells and hepatocytes. Lesions are widespread in the body and include splenic enlargement, swollen and haemorrhagic gastrohepatic and renal lymph nodes, subcapsular petechiae in the kidneys, petechial and ecchymotic haemorrhages in the heart walls and serosal surfaces, oedema of the lungs, hydrothorax and haemorrhages of the pleura. The pathogenesis of the haemorrhages appears to be largely related to the development of disseminated intravascular coagulation and the destruction of megakaryocytes (Rodriquez et al. 1996). There is a marked leukopenia in acute cases. The virus does not appear to replicate in T and B lymphocytes and the associated lymphopenia is thought to be due to apoptosis of lymphocytes and necrosis of lymphoid organs (Carrasco et al. 1996). In chronic cases of ASF, lesions are largely confined to the respiratory tract and include pneumonia, fibrinous pleuritis and pericarditis, pleural adhesions and hyperplasia of lymphoreticular tissues.

Asfarviridae

African swine fever

Pathogenesis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree