Arthropods That Infect and Infest Domestic Animals

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, the reader should be able to do the following:

• Describe the subclass Mandibulata and the subclass Chelicerata.

• Identify the three types of arthropodan parasites that are reportable to the USDA.

• Identify and give examples of arthropods that serve as causal agents themselves.

• Identify and give examples of arthropods that serve as producers of venoms or toxic substances.

• Identify and give examples of arthropods that serve as vectors of diseases.

• Compare and contrast facultative myiasis and obligatory myiasis.

• Compare and contrast localized and generalized demodicosis.

• Compare and contrast insects and acarines.

Key Terms

Arthropodology

Mandibulata

Chelicerata

Crustaceans

Myriopodans

Insects

Dictyopterans

Coleopterans

Lepidopterans

Hymenopterans

Mallophaga

Egg stage

Nit

Nymph

Adult stage

Pediculosis

Diptera

Periodic parasite

Buffalo gnat

New World sand flies

No-see-ums, punkies, sand flies

Queensland itch, sweat itch, sweet itch, summer dermatitis

Biting house fly or stable fly

Horn fly

Sheep ked

Hippoboscid fly

Face fly

Myiasis

Facultative myiasis

Obligatory myiasis

Spiracular plate

Screwworm fly

Reportable parasite

Reportable parasites (this is NOT a repeat)

Wolves, warbles

Ox warbles, cattle grubs

Gadding

Horse bots or stomach bots

Nasal bots or nasal bot flies

Siphonapterans

Siphonapterosis

Flea dirt or flea frass

Acariasis

Pedicels or stalks

Suckers on pedicels

Sarcoptidae family

Psoroptidae family

Scabies

Scaly leg

Foot and tail mites

Demodicosis

Localized demodicosis

Generalized demodicosis

Northern poultry mites

Red mites of poultry

Tropical rat mite

Walking dandruff

Empodia

Palps

Chelicerae

Hypostome

Pedipalps

Scutum

Inornate tick

Ornate tick

Borreliosis

Tick paralysis

Argasid or soft tick

Ixodid or hard ticks

Seed ticks

Spinose ear tick

Fowl tick

Brown dog tick

American dog tick or wood tick

Lone star tick

Gulf coast tick

Texas cattle fever tick or North American tick

Continental rabbit tick

The study of arthropods is referred to as arthropodology. Arthropods, members of the phylum Arthropoda, are important in veterinary parasitology for several reasons. Arthropods (1) serve as causal agents themselves by producing pathology or disease in domesticated or wild animals (or in humans); (2) serve as intermediate hosts for helminths (flukes, tapeworms, and roundworms) and protozoans (single-cell organisms) that infect domesticated or wild animals (or humans); (3) serve as vectors for bacteria, viruses, spirochetes, chlamydial agents, and other pathogens that produce disease in domesticated or wild animals (or humans); and (4) produce venoms and other substances that may be toxic to domesticated or wild animals (or humans). From one to four of these important criteria are true for each group of arthropods.

The phylum Arthropoda is broken down into several subphyla, two of which are important in veterinary parasitology. These two subphyla are the Mandibulata (crustaceans, myriopodans, and insects) and the Chelicerata (mites, ticks, spiders, and scorpions).

Crustaceans

Crustaceans are important in veterinary medicine for several reasons. First, crustaceans may be causal agents themselves when they serve as ectoparasites of fishes and amphibians. Tiny, microscopic crustaceans, such as Argulus species (Figure 13-1), parasitize the skin and gills of aquatic animals and can produce significant pathology. Crustaceans such as crabs can also be important as causal agents when they are swallowed by dogs that frequent beaches; in this scenario, crustaceans act as foreign bodies within the stomach or other portions of the gastrointestinal tract. Crustaceans may also serve as intermediate hosts for certain helminth parasites of domesticated animals. For example, the crayfish serves as the intermediate host for Paragonimus kellicotti, the lung fluke of dogs and cats. Certain aquatic copepods serve as first intermediate hosts for Diphyllobothrium latum and Spirometra mansonoides, pseudotapeworms of dogs and cats. Finally, certain freshwater crustaceans serve as the intermediate host for Dracunculus insignis, the guinea worm, a subcutaneous parasite of dogs.

Myriopodans

The class Myriopoda comprises the centipedes and the millipedes. This strange class of arthropods is important because its members produce venoms or toxic substances.

Parasite: Centipedes

Host: None

Location: Free in environment

Distribution: Truly poisonous centipedes in jungles and dense vegetation worldwide with exception of North America

Derivation of Name: Hundred-legged

Common Name: Centipede

Transmission Route: Not transmitted

Centipedes are usually small, terrestrial arthropods, predatory on creatures smaller than themselves. Centipedes have one pair of legs for every body segment. On the anterior end, they possess poison claws that connect to large poison glands. Centipedes often subdue their prey with these poison claws. It is important to note, however, that most of the truly poisonous centipedes are restricted to the jungles and areas of dense vegetation throughout the world and not to the continent of North America. Some pet stores sell exotic varieties of centipedes, and veterinarians are infrequently asked to “treat” these exotic arthropods; however, a medical arthropodologist (or entomologist) might be consulted. Great care should be taken when handling all centipedes because they can bite. The bite of some of the larger centipede varieties has been likened to the sting of a hornet.

Parasite: Millipedes

Host: None

Location: Free in environment

Derivation of common Name: Thousand legged

Distribution: Truly poisonous centipedes in jungles and dense vegetation worldwide with exception of North America

Transmission Route: Not transmitted

Common Name: Millipede

Millipedes are also small, terrestrial arthropods. Whereas centipedes are predatory on smaller creatures, millipedes are vegetarians. Millipedes have two pairs of legs for every body segment; remember that centipedes have only one pair. Beneath each pair of legs are repugnatorial glands that contain caustic substances capable of burning the skin. Millipedes are able to “squirt” these caustic, irritating substances onto the skin of any creature that might threaten them. As with the centipedes, most of the truly poisonous millipedes are restricted to the jungles and areas of dense vegetation throughout the world and not to the continent of North America. Some tribal people in these jungle areas grind up caustic millipedes and dip their arrow tips into the “juice” to make poisonous arrows. Although centipedes are sold as exotic pets in some pet stores, millipedes do not make good family pets.

Insects

A major portion of this chapter discusses the orders of the class Insecta and their place in veterinary parasitology. The following orders are discussed:

Order: Dictyoptera (cockroaches)

Order: Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths)

Order: Hymenoptera (ants, bees, and wasps)

Order: Mallophaga (chewing or biting lice)

Order: Anoplura (sucking lice)

Order: Diptera (two-winged flies)

Dictyoptera (Cockroaches)

Cockroaches are members of the order Dictyoptera. These disgusting creatures are perhaps the most commonly occurring insects that may actively “infest” a veterinary clinic. Because of their voracious feeding habits and their close association with stored food products (e.g., dried dog and cat food), cockroaches are often associated with the nocturnal environment of the veterinary clinic. Cockroaches habitually disgorge portions of their partly digested food and also defecate wherever they roam and feed. Under the proper circumstances, cockroaches may be incriminated in the natural transmission of pathogenic organisms, such as Salmonella species, to both humans and domesticated animals.

Coleoptera (Beetles)

Members of the order Coleoptera, or beetles, are important because they may serve as intermediate hosts for certain parasites of domesticated animals. Dung beetles serve as intermediate host for Spirocerca lupi, the roundworm that produces esophageal nodules in dogs, and for Gongylonema species, a roundworm found in the tissues of the oral cavity and esophagus of goats and swine. Beetles can also serve as the intermediate host for the swine acanthocephalan, Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus.

Parasite: Blister beetles

Host: None

Location: Free in environment

Distribution: Continental United States and Canada

Derivation of Genus: Based on individual type of Beetle

Transmission Route: Usually ingested

Common Name: Blister beetles

Certain types of beetles, commonly called blister beetles, produce within their tissues a toxic substance called cantharidin (Figure 13-2). If these beetles are ingested by a mammalian host, they can produce a blistering of the skin, the oral mucosa, and the epithelium lining the alimentary tract. These beetles often infest the earth immediately below alfalfa hay, and when the hay is harvested, the beetles may be collected and subsequently fed to horses. When horses ingest these beetles, a fatal colic often results. Blister beetles have been referred to as “Spanish fly,” a type of aphrodisiac or “love potion”; however, blister beetles are caustic and will burn living tissues and should not be used as an aphrodisiac.

Lepidoptera (Butterflies and Moths)

Members of the order Lepidoptera have two life cycle stages—the adult stage and the larval, or caterpillar, stage—that may be pathogenic to domestic animals. Some moths and butterflies in certain parts of Southeast Asia feed on the lachrymal (lacrimal) secretions (tears) of domestic and wild animals. These are exotic creatures, not native to North America. Some moths and butterflies from these exotic regions also have been known to suck blood.

Several species of larval moths and butterflies found in North America are covered with tiny, urticating, or stinging, hairs. Because caterpillars are often slow moving, these hairs serve as defense mechanisms against their predators. These stinging hairs cause significant stings in humans and domestic animals.

Hymenoptera (Ants, Bees, and Wasps)

The veterinarian should remember three basic facts about ants, bees, wasps, and hornets (members of the order Hymenoptera). First, “fire ants” are indigenous to the southeastern United States and can bite and sting almost any domesticated animal. “Downer cows” and newborn animals (weak, young lambs and calves and hatchling chicks) are particularly at risk to the perils of fire ants. Fire ants can attack any animal with which they come in contact. Second, bees, wasps, and hornets can sting domestic animals, particularly curious dogs and cats. These are minor envenomizations, seldom resulting in the death of an animal. Third, after being released in Brazil, Africanized honeybees, or “killer bees,” have spread throughout South America and have crossed the border separating Texas and Mexico. Each year, these bees invade farther into the united states. Almost any domestic animal (and humans) can be at risk of inadvertently disturbing a ground hive containing these bees and arousing its inhabitants. Death will often result from thousands of stings from these killer bees. Bees and wasps can cause anaphylactic reactions in allergic animals and humans. If not treated, these reactions can be severe enough to cause death.

If the veterinary diagnostician suspects that ants, bees, wasps, or hornets may be causing problems, the intact Hymenopteran should be collected in a sealed container containing 10% formalin or ethyl alcohol and submitted to an entomologist for identification.

Hemiptera (True Bugs)

Parasite: Reduviid bugs

Host: Dogs and humans

Location: On host lips & skin of mouth when feeding

Distribution: Species can be found worldwide

Derivation of Genus: None found

Transmission Route: Periodic parasite

Common Name: Kissing bugs

The veterinary diagnostician should remember the following basic facts about true bugs (members of the order Hemiptera). There are two groups of hemipterans that are of veterinary importance: reduviid bugs (“kissing bugs”) and bedbugs. Reduviid bugs are periodic parasites; that is, they make frequent visits to the host to obtain a blood meal. Kissing bugs serve as intermediate hosts for Trypanosoma cruzi, a protozoan parasite that can produce a rare disease called Chagas disease in humans and dogs. This disease is also called South American trypanosomiasis and is rarely diagnosed in the United States. T. cruzi infects a variety of internal organs; its infective stages swim in the blood of an infected host. Kissing bugs take blood meals from infected hosts and incubate the parasite in their intestinal tracts. The parasites are then transmitted to uninfected mammals as the bugs defecate. After taking a blood meal from a host, a kissing bug turns around and defecates on the feeding site. This inoculates the infective trypanosomes into the uninfected host. Kissing bugs play a key role in the transmission of Chagas disease.

Parasite: Cimex lectularius

Host: Humans, rabbits, poultry, and pigeons

Location: On host when feeding

Distribution: North America, Europe and Central Asia

Derivation of Genus: Latin for bug

Transmission Route: Periodic parasite

Common Name: Bed bug

Bedbugs, Cimex lectularius, are the second type of hemipteran important in veterinary parasitology. Bedbugs are dorsoventrally flattened, wingless hemipterans with a three-segmented proboscis tucked under the thorax and ventral “stink glands” producing a characteristic “bedbug odor,” that often infest human dwellings. They have operculated ova that are deposited on mattresses, in wall cracks and crevices, and under peeling wall paper. They are periodic parasites, making frequent visits to the host to obtain a blood meal. Bedbugs are nocturnal feeders. They are diagnosed by the identification of wingless adult hemipterans, characteristic bed bug odor, and identification of operculated ova in the host environment. Although bedbugs are most often incriminated as human parasites, they may also be found in rabbit colonies, poultry houses, and pigeon colonies, preying on domesticated animals (Figure 13-3). Unlike kissing bugs, bedbugs do not serve as intermediate hosts for pathogenic agents that infect humans or domestic animals.

If the veterinary diagnostician suspects that reduviid bugs or bedbugs may be causing problems, the intact hemipteran should be collected and stored in 10% formalin or ethyl alcohol and submitted to an entomologist for identification.

Parasite: Rhodnius species, Panstrongylus species, and Triatoma species

Host: Dogs, humans, opossums, cats, guinea pigs, armadillos, rats, raccoons, and monkeys

Location of Adult: Lips and skin of the mouth when feeding (periodic parasites)

Distribution: South America, Central America, and parts of southwest and western United States (i.e., Texas, Arizona, California, New Mexico, etc.)

Derivation of Genus: Rhodnius – rose, Panstrongylus – all round, Triatoma – cut into three

Transmission Route: Fly or move from host to host

Common Name: Kissing bugs

Rhodnius, Panstrongylus, and Triatoma species are known as the “kissing bugs” because they like to feed on mucocutaneous junctions like those between the lips and the skin of the mouth. They appear to be “kissing” the host. The adults have three body portions: head, thorax, and abdomen. These species are winged hemipterans capable of flying. They have a three-segment proboscis reflexed back (tucked) under the thorax. The ova can be found in the environment of the host but are not usually observed. “Kissing bugs” are periodic parasites and voracious blood-feeders. They do not reside upon the host but frequent the host to obtain a blood meal. The kissing bugs serve as intermediate hosts for Trypanosoma cruzi, a protozoan parasite. These parasites reside in the host’s environment and travel to the host to obtain their blood meal. They transmit T. cruzi to dogs and humans but may feed on other mammalian hosts. These other hosts may serve as reservoirs for T. cruzi. Humans infected with T. cruzi develop the disease called Chagas disease. Diagnosis is made by identifying the kissing bug within the host’s environment, such as within the thatched roof of a hut and in cracks and crevices of mud walls.

Mallophaga (Chewing or Biting Lice) and Anoplura (Sucking Lice)

Lice are some of the most prolific ectoparasites of domesticated and wild animals. There are two orders of lice: Mallophaga, the chewing or biting lice, and Anoplura, the sucking lice. Lice are dorsoventrally flattened, wingless insects. As insects, lice have bodies divided into three divisions: (1) the head, with mouthparts and antennae; (2) the thorax, with three pairs of legs and noticeable lack of wings; and (3) the abdomen, the portion that bears the reproductive organs. These body divisions and their relationship to each other are important in diagnostic veterinary parasitology.

Parasite: Mallophagan species

Host: Mammals and birds

Location of Parasite: In and among the hairs and feathers of the respective hosts.

Distribution: Worldwide

Derivation of Genus: Wool eaters

Transmission Route: Animal-to-animal contact

Common Name: Chewing lice

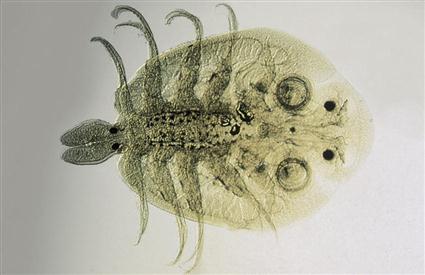

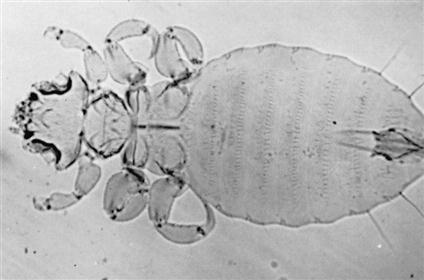

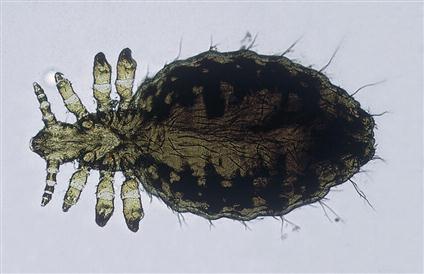

Members of the order Mallophaga (chewing or biting lice) are usually smaller than members of the order Anoplura (sucking lice). Mallophagans are usually yellow and have a large, rounded head. The mouthparts are mandibulate and are adapted for chewing or biting. Characteristically, the head of every chewing louse is wider than the widest portion of the thorax. On the thorax are the three pairs of legs, which may be adapted for clasping or for moving rapidly among feathers or hairs. Chewing (biting) lice may parasitize birds, dogs, cats, cattle, sheep, goats, and horses. Chewing lice of cattle and fowl include Damalinia bovis (Figure 13-4), Goniocotes gallinae (Figure 13-5), and Menacanthus stramineus (Figure 13-6).

Parasite: Anopluran species

Host: Domestic animals except cats and birds

Location of Parasite: Clinging to the host’s hair

Distribution: Worldwide

Derivation of Genus: Unarmed tail

Transmission Route: Animal-to-animal contact

Common Name: Sucking lice

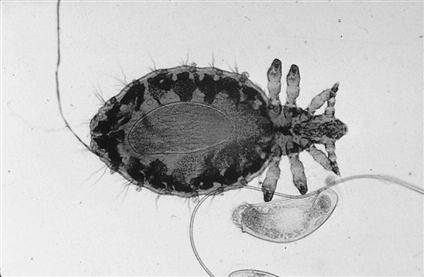

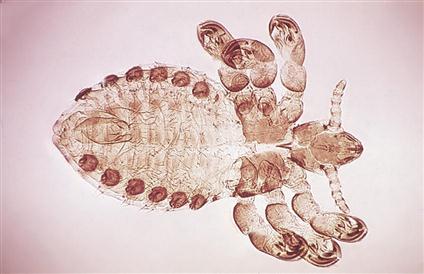

Members of the order Anoplura (sucking lice) are larger than chewing lice. These lice range from red to gray; the color usually depends on the amount of blood that has been ingested from the host. Anoplurans have three body portions: the head, thorax, and abdomen. The adult anoplurans are wingless. In contrast to the large-headed mallophagans, anoplurans have a head that is narrower than the widest part of the thorax. Their mouthparts are of the piercing type and are adapted for sucking. Their pincerlike claws are adapted for clinging to the host’s hairs. Interestingly, although they are found on many species of domestic animals, sucking lice do not parasitize birds or cats. Sucking lice of sheep, swine, monkeys, and dogs include, respectively, Solenopotes capillatus (Figure 13-7), Haematopinus suis (Figure 13-8), Pedicinus obtusus (Figure 13-9), and Linognathus setosus (Figure 13-10) and are species specific.

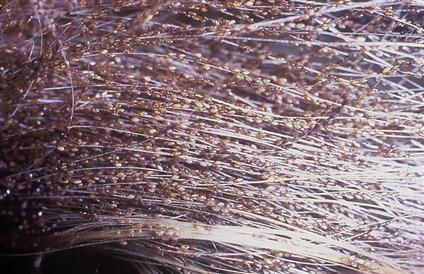

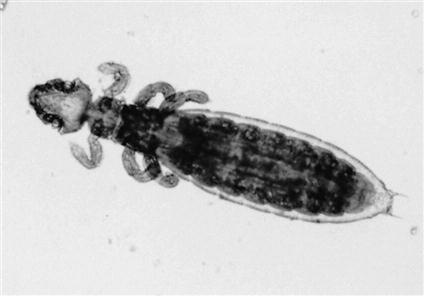

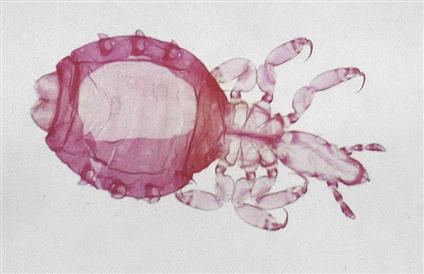

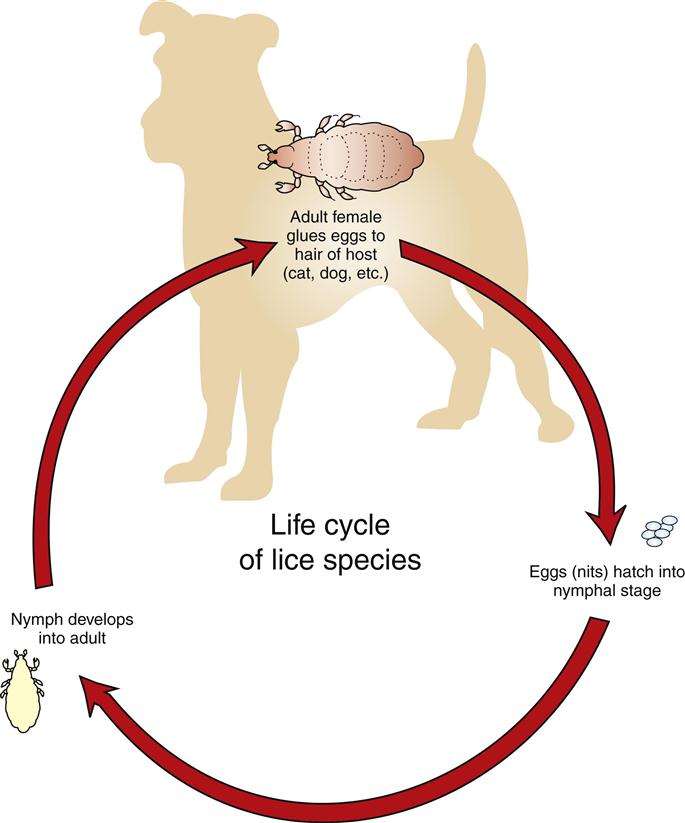

Anoplurans and mallophagans have a life cycle consisting of three developmental stages. The egg stage, which is also called a nit, is tiny, approximately 0.5 to 1 mm in length. Nits are oval and white and are usually found cemented to the hair or feather shaft. Figure 13-11 shows Linognathus setosus, a gravid female sucking louse and an associated nit collected from a dog. Nits hatch about 5 to 14 days after being laid by the adult female louse. Thousands of nits can be “cemented” by female lice to the hair coat of domesticated animals (Figure 13-12). The nymphal stage is similar in appearance to the adult louse. However, the nymph is smaller and lacks functioning reproductive organs and genital openings. There are three nymphal stages, each progressively larger than its predecessor. The nymphal stage lasts from 2 to 3 weeks. The adult stage is similar in appearance to the nymphal stage, except that it is larger and has functional reproductive organs (Figure 13-13). The male and female lice copulate, the female louse lays eggs, and the life cycle begins again, taking 3 to 4 weeks to complete. Nymphal and adult stages may live no longer than 7 days if removed from the host. Eggs hatch within 2 to 3 weeks during warm weather, but seldom hatch off of the host.

Lice usually are transmitted by direct contact, but all life stages may be transmitted by fomites, inanimate objects such as blankets, brushes, and other grooming equipment. Lice are easily transmitted among young, old, and malnourished animals. Veterinarians often cannot determine why certain animals in a flock or herd are heavily infested, whereas others have only a few lice.

Infestation by lice (either mallophagan or anopluran) is referred to as pediculosis (Figure 13-14). Sucking lice can ingest blood to such a degree that they produce severe anemia in the parasitized host; fatalities can occur, especially in young animals. The packed cell volume can decrease as much as 10% to 20%. As many as a million lice may be found on a severely infested animal. Infested animals become more susceptible to other diseases and parasites and may succumb to stresses not ordinarily pathologic to uninfested animals. When animals are poorly fed and kept in overcrowded conditions, they often become severely infested with lice and quickly become anemic and unthrifty.

Careful examination of the hair coat or feathers of infested animals easily reveals the presence of adult lice and their accompanying nits. Hair clippings also serve as a good source for collecting lice. For those animals with a thick hair coat, pediculosis may be overlooked. A hand-held magnifying lens or a binocular headband magnifier (e.g., Optivisor) may assist in isolation of adult or nymphal lice crawling through or clinging to hair or feathers or tiny nits cemented to individual hairs.

When lice or nits are isolated, they may be collected with tiny thumb forceps and placed within a drop of mineral oil on a glass microscope slide. A coverslip should be placed over the specimen and the slide examined using the 4× or 10× objective of the microscope (Figure 13-15).

Identification of louse to genus and specific epithet is quite difficult. It is better to identify the specimen as being anopluran (sucking) versus mallophagan (chewing or biting). The veterinary diagnostician should remember that the head of every chewing louse is wider than the widest portion of its thorax. The typical sucking louse has a head that is narrower than the widest part of the thorax.

Lice of Mice, Rats, Gerbils, and Hamsters

Parasite: Polyplax serrata

Host: Mouse

Location of Parasite: Within hair coat

Distribution: Worldwide

Derivation of Genus: Many plates

Transmission Route: Direct contact between mice

Common Name: Mouse louse

Polyplax serrata is the house mouse louse. This louse is an anopluran (sucking louse), with mouthparts morphologically adapted for sucking blood from its host. Anoplurans are generally more debilitating than mallophagans (chewing lice). P. serrata is 0.6 to 1.5 mm long. It is a slender, yellow-brown to white louse with a head that is narrower than the widest part of the thorax. As with most lice, P. serrata is large enough to be detected by careful visual inspection of the hair coat or by microscopic examination of pulled hairs. The adult stage of P. serrata is most likely found on the forebody of the mouse. Oval nits may be seen attached near the base of the hair shafts.

Clinical signs associated with infestation by P. serrata include restlessness, pruritus, anemia, unthrifty appearance, and death. The diagnostician should not attribute dermal signs to pediculosis unless a louse or a nit is detected. The dermal signs may be the result of other causes, such as concurrent infestation with mites. Therefore, it is wise to examine an animal or hair sample thoroughly, rather than ceasing when a single parasite has been identified.

P. serrata is transmitted by direct contact between mice. Because lice are species specific, cross-contamination of other species housed in the same area and transmission to humans are not considerations. However, P. serrata may serve as a vector for several rickettsial organisms and should therefore be handled with caution.

Parasite: Polyplax spinulosa

Host: Rat

Location of Adult: Within the hair coat

Distribution: Worldwide

Derivation of Genus: Many plates

Transmission Route: Direct animal-to-animal contact

Common Name: Rat louse

As with P. serrata in the mouse, the rat louse, Polyplax spinulosa, is an anopluran louse (sucking louse). P. spinulosa is similar to P. serrata, also having a narrow head compared with the thorax. Similarly, its mouthparts are adapted for sucking blood from the rat.

P. spinulosa may be detected by gross visual examination of the midbody and shoulders of the rat. Hair may be pulled from these areas and examined for nits, nymphs, and adults. Nits are often found attached to the base of the hair shafts. Nymphs resemble small, pale adult lice. Clinical signs include restlessness, pruritus, anemia, debilitation, and, potentially, death. Transmission of the rat louse is by direct contact. Ivermectin has been used successfully to treat lice in rodents. Because lice are species specific, transmission to other animals or humans is not a concern. P. spinulosa is a vector responsible for spread of Haemobartonella muris and Rickettsia typhi between rats. R. typhi also can be transmitted from infected rats to humans by rat fleas.

Parasite: Hoplopleura meridionidis

Host: Gerbil

Location of Adult: Within the hair coat

Distribution: Not Found

Derivation of Genus: Unknown

Transmission Route: Direct animal-to-animal contact

Common Name: Gerbil louse

The louse found on the common pet store gerbil is Hoplopleura meridionidis. It is interesting that there are no records of lice reported from either the common pet store hamster, Cricetus cricetus, or the common laboratory hamster, Mesocricetus auratus.

Lice of Guinea Pigs

Parasite: Gliricola porcelli and Gyropus ovalis

Host: Guinea pig

Location of Adult: Within the hair coat

Distribution: Predominantly South & North America

Derivation of Genus: Unknown

Transmission Route: Direct animal-to-animal contact

Common Name: Guinea pig lice

Gliricola porcelli and Gyropus ovalis are the lice of guinea pigs. Both species belong to the order Mallophaga (chewing lice). These lice differ from those of the order Anoplura (sucking lice) by their wide, triangular heads. Chewing lice have a strong pair of mandibles, which are used to abrade skin and obtain cutaneous fluids. G. porcelli and G. ovalis belong to the family Gyropidae, distinguished by having one or no claws on the second and third pairs of legs.

Gliricola porcelli, the slender guinea pig louse, is 1 to 1.5 mm × 0.3 to 0.44 mm (Figure 13-16). Gyropus ovalis, as its name implies, is more oval than G. porcelli and measures 1 to 1.2 mm × 0.5 mm (Figure 13-17). The head of G. ovalis is much broader than that of G. porcelli. Of these two lice, G. porcelli is the more common.

Guinea pig lice can be detected antemortem by careful inspection of the hair coat, either grossly or with a hand-held magnifying lens. Postmortem, a method similar to that used to detect lice in other species of animals may be useful. That is, a piece of the pelt from the dead animal may be placed in a covered Petri dish and placed under a mild heat source, such as a small reading lamp. In a short time, as the pelt cools, the lice migrate toward the warmth of the lamp, to the tips of the hairs. The lice can be easily observed grossly or with a hand-held magnifying lens.

Light infestations of G. porcelli and G. ovalis usually cause no clinical signs. In heavy infestations, however, alopecia and scablike areas may develop, especially in the areas caudal to the ears of the guinea pig. Excessive scratching may be noticed. Ivermectin can be used to treat G. porcelli and G. ovalis in guinea pigs.

Transmission of G. porcelli and G. ovalis is by direct contact with another host guinea pig or bedding or other fomites from infested guinea pigs. As with other lice, lice of guinea pigs are species specific and do not cross-infest other species, including humans.

Lice of Rabbits

Parasite: Hemodipsus ventricosus

Host: Rabbit

Location of Adult: Within the hair coat

Distribution: Not found

Derivation of Genus: Unknown

Transmission Route: Direct animal-to-animal contact

Common Name: Rabbit louse

Hemodipsus ventricosus is not typically found on domestic rabbits; however, when infestation does occur, it is especially debilitating. H. ventricosus is an anopluran louse, with a head narrower than the widest part of the thorax. Its mouthparts are specially designed for sucking blood from the host. It has a small thorax and a large, rounded abdomen covered with numerous long hairs. Adult H. ventricosus are 1.2 to 2.5 mm long and can be observed antemortem by careful visual examination of the hair coat, especially on the dorsal and lateral aspects of the rabbit. On postmortem examination, hairs may be pulled and placed in a Petri dish under a warm lamp and examined with a dissecting microscope or magnifying glass. Adult lice are drawn by the warmth of the lamp to the tips of the hairs. The oval nits of H. ventricosus are 0.5 to 0.7 mm in length and may be found attached to the base of the hair shafts by pulling the fur and examining it microscopically.

Clinical signs of H. ventricosus include alopecia and ruffled fur. Rabbit lice are avid bloodsuckers, so anemia may occur in severe infestations.

H. ventricosus is transmitted from rabbit to rabbit by prolonged direct contact. This mostly occurs between a doe and her litter. Although H. ventricosus is not considered zoonotic, it is a vector of Francisella tularensis, the etiologic agent that causes tularemia.

Diptera (Two-Winged Flies)

The order Diptera is a very large, complex order of insects. As adults, all members have one pair of wings (two wings), thus the ordinal name Diptera; di means “two,” and ptera means “wing.” The members vary greatly in size, food source preference, and developmental stage or stages that parasitize animals or produce pathology. With regard to their role as ectoparasites, dipterans produce two contrasting pathologic scenarios. As adults, they may feed intermittently on vertebrate blood, saliva, tears, and mucus; as larvae, they may develop in the subcutaneous tissues or internal organs of the host. When adult dipterans make frequent visits to the vertebrate host and intermittently feed on that vertebrate host’s blood, they are referred to as periodic parasites. When dipteran larvae develop in the tissue or organs of vertebrate hosts, they produce a condition known as myiasis.

As periodic parasites, blood-feeding dipterans can be classified in several ways based on the way in which the adult male and female dipterans feed on vertebrate blood and on their food preference. There are certain dipteran groups in which only the females feed on vertebrate blood; these female flies require vertebrate blood for laying their eggs. Included in this group are biting gnats (Simulium, Lutzomyia, and Culicoides spp.), the mosquitoes (Anopheles, Aedes, and Culex spp.), the horseflies (Tabanus spp.), and the deerflies (Chrysops spp.).

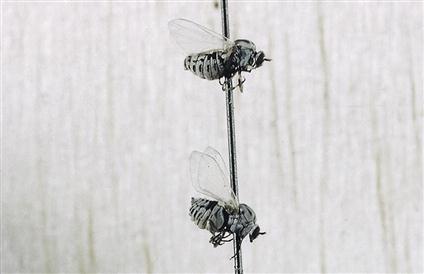

In the second group of blood-feeding dipterans, both male and female adult flies require a vertebrate blood meal. These species include Stomoxys calcitrans, the stable fly; Haematobia irritans, the horn fly; and Melophagus ovinus, the sheep ked.

Another dipteran fly, Musca autumnalis, feeds on mucus, tears, and saliva of large animals, particularly cattle.

Periodic Parasites of Which Only Adult Females Feed on Vertebrate Blood

In the first dipteran group of periodic parasites, only the female dipterans feed on vertebrate blood. The tiniest members of this group are the biting gnats of Simulium, Lutzomyia, and Culicoides species.

Parasite: Simulium species

Host: Domesticated animals, poultry, and humans

Location of Adults: Surface of skin when feeding; otherwise, in the vicinity of swiftly flowing streams

Distribution: Worldwide, but not in Hawaii or New Zealand

Derivation of Genus: At the same time

Transmission Route: Fly from host to host

Common Name: Black flies or buffalo gnats

Simulium Species (Black Flies)

Members of the genus Simulium are commonly called black flies, although they may vary from gray to yellow, or buffalo gnats, because their thorax humps over their head, giving the appearance of a buffalo’s hump (Figure 13-18). These are tiny flies, ranging from 1 to 6 mm in length. The adults have broad, unspotted wings that have prominent veins along the anterior margins. They have serrated, scissorlike mouthparts, and thus their bites are very painful. Because the females lay eggs in well-aerated water, these flies are often found in the vicinity of swiftly flowing streams. They move in great swarms, inflicting painful bites and sucking the host’s blood. These flies are voracious feeders (periodic parasites) but only the female flies feed on vertebrate blood. The males feed on nectar and pollen. The females fly great distances to find vertebrate blood. The female needs a vertebrate blood meal to lay her eggs. These flies may keep cattle from grazing or cause them to stampede. The ears, neck, head, and abdomen are favorite feeding sites. Black flies also feed on poultry and can serve as an intermediate host for a protozoan parasite known as Leucocytozoon species.

Black flies prefer the daylight hours and tend to be active in open air. Repellents may offer some relief from these flies. The best method of preventing infestation with black flies is by keeping the equine or bovine hosts in the barn during daylight hours.

Black flies are most often collected in the field (usually in the vicinity of their breeding sites, swiftly flowing streams) and not found on animals presenting to a veterinary clinic. They are diagnosed by their small size, humped back, and strong venation in the anterior region of the wings. Identification of black flies to the level of genus is probably best left to an entomologist.

Parasite: Lutzomyia species and Phlebotomus species

Host: Mammals of many species, reptiles, avians, and humans (Lutzomyia species): mammals, reptiles, avians, and humans (Phlebotomus species)

Location of Adult: On skin surface when feeding, otherwise, in dark, moist, and organic environments

Distribution: Worldwide (Lutzomyia species); tropics, subtropics, and Mediterranean regions (Phlebotomus species)

Derivation of Genus: Phlebotomus – vein cutting, Lutzomyia – Lutz was a renowned entomologist and myia means “fly”

Transmission Route: Fly from host to host

Common Name: New World sand flies (Lutzomyia species); sand flies (Phlebotomus species)

Lutzomyia Species (New World Sand Flies) and Phlebotomus Species

Members of the genus Lutzomyia are commonly referred to as New World sand flies. Phlebotomus species are commonly referred to as “sand flies.” These two genuses represent the group of flies called the phlebotomine sand flies. They are tiny, mothlike flies, rarely more than 5 mm in length. A key feature for identification is that the body (head, thorax, and abdomen) is hirsute (covered with fine hairs). Lutzomyia and Phlebotomus species tend to be active only at night and are weak fliers. These tiny flies transmit a zoonotic protozoan parasite known as Leishmania species and the rodents that reside in the burrows in which the flies live serve as reservoirs for Leishmania species.

As with black flies, sand flies most often can be collected in the field and are not found on animals presenting to a veterinary clinic. The adult flies are weak fliers and are often collected in rodent burrows, where they breed in moist organic debris. Phlebotomine sand flies can be diagnosed by their small size and hairy wings and bodies. Identification of sand flies is probably best left to an entomologist.

Parasite: Culicoides species

Host: Domestic animals and humans

Location of Adult: On the skin surface when feeding; otherwise, in their aquatic or semiaquatic breeding grounds

Distribution: Worldwide

Derivation of Genus: Mosquito-like

Transmission Route: Fly from host to host

Common Name: No-see-ums, punkies, or sand flies (not to be confused with the phlebotomine sand flies: Lutzomyia and Phlebotomus species)

Culicoides Species (No-See-Ums)

Culicoides gnats are also commonly known as no-see-ums, punkies, or sand flies. They are tiny gnats (1 to 3 mm in length) and similar to black flies in that they inflict painful bites and suck the blood of their hosts. The adults have a short proboscis and mottled or spotted wings with hairs on the wing margins. They are active at dusk and at dawn, especially during summer months. The adults tend to be found around their aquatic or semiaquatic breeding grounds when not feeding. The developmental stages are primarily aquatic and are seldom observed in a veterinary clinic setting. These female gnats tend to feed on the dorsal or ventral areas of the host during dusk and evening hours; the feeding site preference depends on the species of biting gnat. Horses often become allergic to the bites of Culicoides species, scratching and rubbing these areas, causing alopecia, excoriations, and thickening of the skin. This condition has several names, including Queensland itch, sweat itch, and sweet itch. Because this condition is often seen during the warmer months of the year, it is also referred to as summer dermatitis. The best prevention for these flies is stabling animals during the hours between dusk and dawn. Repellents may offer some protection against Culicoides species. These flies also serve as the intermediate host for Onchocerca cervicalis, a nematode whose microfilariae are found in the skin of horses. These flies also transmit the blue-tongue virus of sheep.

In contrast to the clear, heavily veined wings of black flies, the wings of Culicoides species are mottled. Identification of Culicoides species is probably best left to an entomologist.

Parasite: Anopheles quadrimaculatus, Aedes aegypti, and Culex species

Host: Mammals, reptiles, avians, and humans

Location of Adult: Skin surface when feeding

Distribution: Worldwide

Derivation of Genus: Anopheles – hurtful, Aedes – unpleasant, Culex – gnat

Transmission Route: Fly from host to host

Common Name: Malaria mosquito (A. quadrimaculatus), yellow fever mosquito (A. aegypti), and mosquito (Culex species)

Anopheles quadrimaculatus, Aedes aegypti, and Culex species (Mosquitoes)

Although they are tiny, fragile dipterans, mosquitoes are some of the most voracious blood-feeders (Figure 13-19) and strong fliers. Mosquitoes plague livestock, and as with black flies, swarms of mosquitoes have been known to keep cattle from grazing or cause them to stampede. The feeding of large swarms of mosquitoes can cause significant anemias in domestic animals. Because of their aquatic breeding environments, large numbers of mosquitoes can be produced from eggs laid in relatively small bodies of water.

Anopheles quadrimaculatus females lay their eggs on the surface of still water. Each egg possesses two lateral corrugated areas called “floats.” These “floats” allow the eggs of Anopheles quadrimaculatus to float on the water’s still surface. At the tip of the Anopheles larval abdomen is a breath pore that lacks a siphon. The larva floats parallel to the surface of the water and wriggles in the water if disturbed. The pupa floats right at the surface of the water and if disturbed, will tumble down to a lower level within the water and slowly float back to the surface.

Aedes aegypti females lie on dry surfaces where water will accumulate. These eggs lack the “floats” of A. quadrimaculatus. The larval A. aegypti has three portions: head, thorax, and abdomen. On the tip of the abdomen is a breathing pore at the tip of the siphon. This mosquito larva floats parallel to the surface of the water and wriggles in the water if disturbed. As with A. quadrimaculatus, the A. aegypti pupa floats right at the surface of the water and if disturbed will tumble down to a lower level within the water and slowly float back to the surface.

Culex species females lay their eggs perpendicular to the surface of water to form a floating “egg raft.” The larval mosquito has three portions: head, thorax, and abdomen. In the tip of the abdomen is a breathing pore at the tip of the siphon. This mosquito larva floats parallel to the surface of the water and wriggles in the water if disturbed. The pupa floats right at the surface of the water and if disturbed will tumble down to a lower level within the water and slowly float back to the surface.

Although they are known for spreading malaria (Plasmodium spp.), yellow fever, and elephantiasis in humans, mosquitoes are probably best known in veterinary medicine as intermediate hosts for the canine heartworm, Dirofilaria immitis.

Many of the repellents on the market are effective against mosquitoes. The repellents must be applied to the entire body at labeled frequencies to provide protection to the animal. In addition, preventing the buildup of small bodies of water on the premises (e.g., water in old tires, small puddles after rains, cleaning water troughs frequently) will help reduce the breeding grounds available to mosquitoes.

The adult and larval body of the mosquito has three portions: head, thorax, and abdomen. Adult mosquitoes have wings and body parts (head, thorax, and abdomen) covered by tiny, leaf-shaped scales. The adult female of the Anopheles species has a proboscis with long palps. The adult female of the Aedes species and Culex species have a proboscis with short palps. Palps are appendages found near the mouth in invertebrate organisms used for sensation, locomotion, and feeding. All females have a pilose (covered with fine hairs) antenna. Identification of both adult and larval Anopheles, Aedes, and Culex species is probably best left to an entomologist.

Parasite: Chrysops species and Tabanus species

Host: Large mammals and humans but small animals and avians can be attacked

Location of Adult: Skin surface when feeding, otherwise, around lakes and ponds

Distribution: Worldwide

Derivation of Genus: Chrysops – golden eye, Tabanus – gadfly

Transmission Route: Fly from host to host

Common Name: Deerflies (Chrysops species) and horseflies (Tabanus species)

Chrysops species (Deerflies) and Tabanus species (Horseflies)

Tabanus species (horseflies) are very large flies (up to 3.5 cm in length) while Chrysops species are smaller with banded wings. They both are heavy-bodied, robust, swift dipterans with powerful wings. These flies also have very large eyes. Horseflies and deerflies are the largest flies in this dipteran group in which only the females feed on vertebrate blood (Figure 13-20). Horseflies are much larger than deerflies. Deerflies have a dark band passing from the anterior to the posterior margin of the wings.