Chapter 9 Applied Anatomy of the Musculoskeletal System

It is beyond the scope of this book to describe all aspects of musculoskeletal anatomy in depth, yet a detailed knowledge of anatomy is fundamental to a lameness diagnostician, as highlighted in the chapters on observation and palpation (see Chapters 5 and 6). Some aspects of anatomy are considered in depth in individual chapters dealing with conditions of specific areas. This chapter considers some philosophical aspects of the importance of anatomical knowledge and describes some basic principles. It also provides illustrations that we hope will help the reader to understand better the three-dimensional aspects of anatomy.

Accurate interpretation of what we see and feel during an examination requires knowledge of what structures we are looking at and palpating. For example, a swelling is noted over the dorsal aspect of the carpus. Is the swelling diffuse and possibly related to a hygroma, periarticular edema, or cellulitis, or is there a discrete swelling, horizontally oriented, reflecting distention of the middle carpal joint? Or is it a longitudinal swelling reflecting distention of the common digital extensor tendon sheath or the tendon sheath of the extensor carpi radialis? If the swelling is longitudinal, are any compressions in the swelling caused by normal retinaculum or adhesions within the sheath (Figure 9-1)? If we examine the sheath by ultrasonography, is the echogenic band extending from the sheath wall to the enclosed tendon normal mesotendon, or is it an adhesion? If diffuse swelling is present around the dorsal aspect of the carpus associated with lameness, how can we tell if the middle carpal joint capsule is distended? We need to know that there is a palmar outpouching of the middle carpal joint on the palmarolateral aspect of the carpus, just distal to the accessory carpal bone. Thus during visual inspection and palpation the clinician should be constantly asking, “What structure am I seeing or palpating, what are its functions, and what would be the consequences of loss of function?” If it has abnormal contour or size, is this the result of swelling of that structure or of an adjacent or underlying structure? Having established what structure is abnormal, the clinician then must consider the best imaging modality. If it is a tendonous or ligamentous structure, ultrasonography probably will provide the most information, but we must remember that it has bony attachments, and damage at those attachments might best be assessed by either radiology or nuclear scintigraphy. So we need to know not only what each structure is, but also the structures to which it is attached.

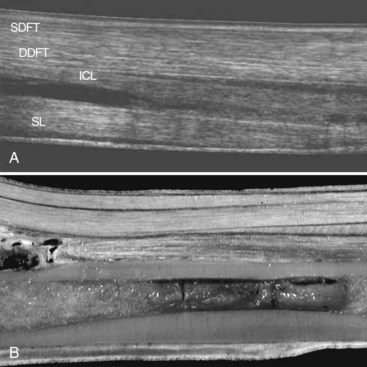

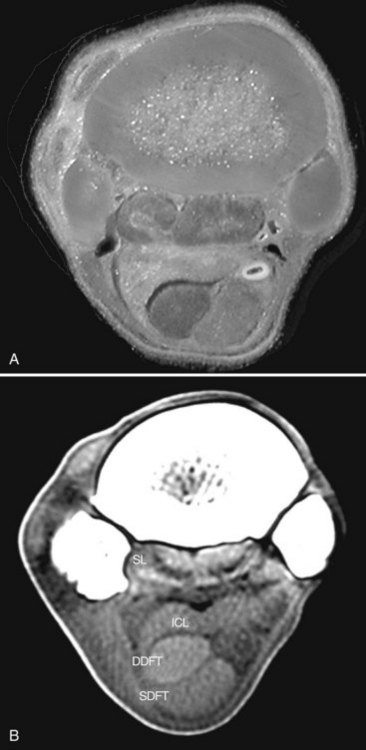

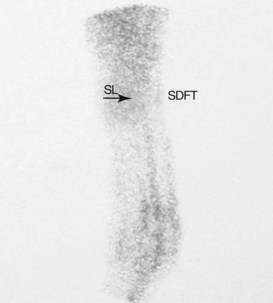

During visual inspection and palpation, we also need to think logically. We know that the superficial and deep digital flexor tendons (SDFT, DDFT), the accessory ligament of the DDFT (ALDDFT), and the suspensory ligament (SL) lie on the palmar aspect of the third metacarpal bone (McIII) (Figure 9-2). Swelling confined to just the medial aspect of the metacarpal region is far more likely to reflect direct trauma to the medial aspect of the limb than sprain or strain of any of the ligamentous or tendonous structures. We need to know that the proximal aspect of the SL lies between the bases (heads) of the second and fourth metacarpal bones and therefore is inaccessible to direct palpation, and that desmitis often may be present without discernible soft tissue swelling (Figure 9-3).

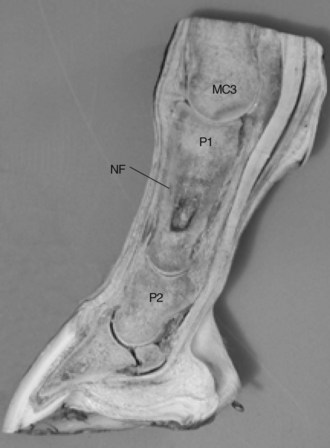

We must be aware of anatomy to realize the possible consequences of trauma to an area. The paucity of soft tissues over the cranial aspect of the stifle makes the patella and the tibial tuberosity vulnerable to direct trauma, hence the risk of fracture after hitting a fixed fence. The lack of soft tissues also means that if the horse hits a thorn hedge, the possibility of a thorn penetrating the femoropatellar joint capsule, resulting in contamination and infection, is quite high. We also need to think about how structures move relative to one another while the horse is in motion. If a steeplechase horse sustains an interference injury on the palmar aspect of the metacarpal region while galloping, the position of the skin laceration probably will not coincide with the level of the laceration in the SDFT (Figure 9-4). We also need to know the relative positions of the laceration and the digital flexor tendon sheath to be aware of the likelihood that the sheath may have been traumatized, and thus the risk of infectious tenosynovitis. Faced with a contaminated wound on the dorsal aspect of a hind fetlock and severe lameness, and the possibility of infection of the metatarsophalangeal joint, we need to know where to expect to see distention of the plantar pouch of the joint capsule and to know that this site is safely accessible for arthrocentesis.

A fundamental principle of lameness investigation is the identification of the source or sources of pain. Although this may be possible through detailed clinical examination, in many instances it is essential to perform diagnostic analgesia (see Chapter 10). A detailed knowledge of the anatomy of nerves, joint capsules and the various outpouchings, tendon sheaths, and bursae is fundamental to safe, accurate performance of perineural and intrasynovial injections.

Knowledge of the sites of major vessels is important when considering the consequences of major laceration to an area and possible avascular areas, and in planning a surgical approach to an area. All bones have one or more nutrient foramina through which major vessels enter. These usually are in standard locations (Figure 9-5). Knowledge of these sites is critical for accurate radiological interpretation because a nutrient foramen appears as a radiolucent area, which should not be confused with a pathological lesion. The position of these intraosseous vessels also has important consequences in considering repair of major long bone fractures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree