Chapter 120 Anemia

INTRODUCTION

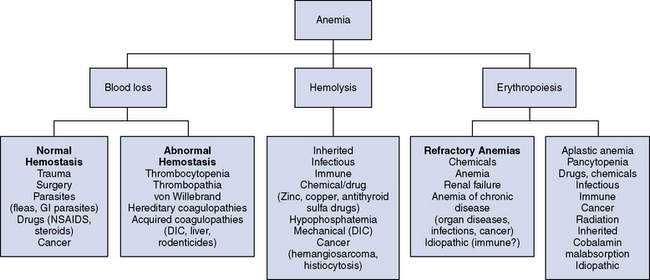

Anemia is defined as a reduction in the oxygen carrying capacity of blood due to decreases in hemoglobin (Hb) concentration and red blood cell (RBC) volume. It is certainly one of the most common laboratory test abnormalities in small animals, particularly in an emergency setting. However, anemia is not a diagnosis and thus further clinical investigations are indicated to define the underlying cause. The three mechanisms leading to anemia are blood loss, hemolysis, and reduced erythropoiesis (Figure 120-1).1-3

CLINICAL SIGNS

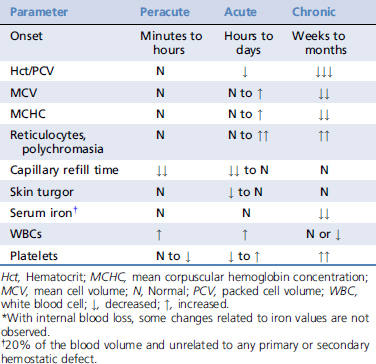

The clinical signs of anemia vary greatly depending on the rapidity of onset, type, and underlying cause. It is of utmost importance to determine if hemorrhage, hemolysis, or a hematopoietic production disorder is causing the anemia. Any form of anemia may be associated with pallor, and this may be the only sign in some animals. However, characteristic signs such as hemorrhage with blood loss–induced anemia (Table 120-1) or icterus or pigmenturia with hemolytic anemia may help the clinician determine the etiology.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree