Chapter 3 Anamnesis (History)

The importance of a detailed clinical history, the anamnesis, cannot be overemphasized. Information is divided into two categories: basic facts necessary for every horse, and additional information from questions tailored to the specific horse. The veterinarian must understand the breed, use, and level of competition of each horse, because prognosis varies greatly among different types of sports horses. Firsthand experience of the particular type of sports horse being examined is useful but is not essential. Clinicians must understand the language associated with the particular sporting event, and this may be a challenge. For some sporting events, understanding the clinical history and having the ability to ask the right questions are like speaking a different language. A veterinarian unfamiliar with the sporting activity should briefly review the type of activities performed and the array of potential lameness problems encountered with them (see Chapter 106Chapter 107Chapter 108Chapter 109Chapter 110Chapter 111Chapter 112Chapter 113Chapter 114Chapter 115Chapter 116Chapter 117Chapter 118Chapter 119Chapter 120Chapter 121Chapter 122Chapter 123Chapter 124Chapter 125Chapter 126Chapter 127Chapter 128Chapter 129). In some instances the veterinarian may lose credibility when talking to trainers or riders, particularly those involved in upper-level competition, if they perceive unfamiliarity.

Clinical History: Basic Information

Signalment

Age

The age, sex, breed, and use of the horse are basic vital facts (Box 3-1). Flexural deformities, physitis, other manifestations of osteochondrosis, and angular limb deformities are age-related problems. Infectious arthritis (hematological origin), lateral luxation of the patella, and rupture of the common digital extensor tendon are conditions usually unique to foals. Emphasis on training skeletally immature, 2- and 3-year-old racehorses causes predictable soft tissue and bone changes, often resulting in stress-related cortical or subchondral bone injury. Liautard observed more than 100 years ago: “When an undeveloped colt, whose stamina is not yet established and constitution not yet confirmed, with tendons and ligaments relatively tender and weak, and bones scarcely out of the gristle, is unwisely condemned to hard labor, it is irrational to expect any other results than lesions of one or another portion of the abused apparatus of locomotion. They will be fortunate if they escape a fate still worse, and become sufferers from nothing worse than mere lameness.”1 This statement aptly summarizes the situation then and now. The high value of races for 2- and 3-year-olds results in high-intensity training for early 2-year-olds, which may result in injury such as maladaptive or nonadaptive remodeling of the third carpal bone (C3), precluding racing at a young age.

BOX 3-1 Anamnesis

Basic and Specific Information

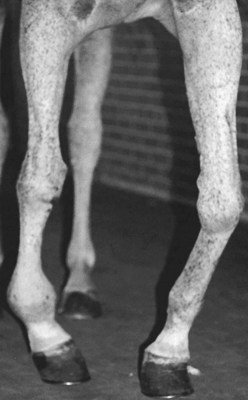

Some problems are unique to older horses (Box 3-2). Overall, osteoarthritis (OA) and other degenerative conditions such as navicular disease are most common but certainly are not unique to the geriatric horse. Some horses have a remarkably early onset of navicular disease or OA despite little physical work, suggesting a genetic predisposition to the condition. These problems worsen with advancing age, particularly if several limbs are involved. In former racehorses, progressive OA is of particular concern; this condition most commonly affects the carpal and metacarpophalangeal joints (Figure 3-1). Occasionally in older horses, severe, progressive OA of the carpometacarpal joint occurs without any history of carpal lameness (Figure 3-2). In some horses, angular deformities (the most common is carpus varus) develop at the carpometacarpal joint. Inexplicably severe OA of the carpometacarpal and middle carpal joints is most commonly seen in Arabian horses (see Chapter 38). Primary OA of this joint is rare in young horses, even in racehorses with middle carpal joint abnormalities, unless C3 slab fracture or infectious arthritis occurs. OA of the coxofemoral joint is rare in horses with the exception of young horses with osteochondrosis, but it does occur in older horses.

BOX 3-2 Summary of Lameness Conditions of the Geriatric Horse

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree