Samuel D.A. Hurcombe

Acute Neurologic Injury

Traumatic head injury can lead to traumatic brain injury (TBI) in horses, and is a common and potentially fatal type of injury. Even when the outcome is successful, treatment can be very expensive, labor-intensive, and time consuming. Although a recent study reported that survival from head injury is higher than once was thought, only 62% of horses were discharged from the hospital after a median hospitalization period of 9 days. Young animals (average age, 1 year) were the most likely to sustain TBI, and in this group, ataxia, abnormal mentation, and nystagmus were among the most common acute clinical signs. Blood chemistry values and cytology were essentially normal in most cases, with only mild increases in activities of the muscle enzymes creatine kinase and aspartate aminotransferase. Packed cell volume was higher in nonsurvivors than in survivors. Horses that were recumbent for more than 4 hours from the time of injury were 18 times less likely to survive than horses with other types of brain injury, whereas those with a basilar bone fracture, such as commonly occurs when horses flip over and sustain poll injury, were 7.5 times less likely to survive. Treatments given to horses with TBI included antiinflammatory agents, diuretics, intravenous fluids, osmotic agents, anticonvulsants, antimicrobials, and antioxidants, with no particular treatment resulting in greater survival. However, this was a retrospective analysis, and judgments about treatment efficacy cannot be made without suitable controls, sufficient statistical power, and consistent injury among subjects. Among the survivors, 90% had some residual neurologic deficit at the time of discharge, but these were not considered life threatening. By 6 months after the TBI, most horses that were discharged from the hospital performed their pre-injury activities up to expectations.

Pathophysiology of Acute Neurologic Injury

Skull fractures can be classified as calvarial, noncalvarial, simple, comminuted, displaced (depressed), nondisplaced, and basilar. Brain injury can be primary (coup or contrecoup) or secondary. In coup injury, tissue trauma (hemorrhage, contusion, laceration) occurs at the site of impact. By contrast, in contrecoup injury, brain tissue distant to the site of impact is injured by acceleration and deceleration forces acting on the brain inside the cranial vault. Secondary injury, which occurs at the site of primary injury and in adjacent penumbral tissues, may be characterized by ischemia, reperfusion injury, inflammation, edema (vasogenic and cytotoxic), decreased oxygen delivery, increases in intracranial pressure (ICP), metabolic derangements (e.g., hypoxia, calcium toxicity, excitatory neurotransmitter activation, adenosine triphosphate depletion), vascular damage, necrosis, and apoptosis.

Management and Therapeutics

It is important to remember that many horses with skull and brain injury also have superficial and deep soft tissue injuries, including lacerations, ocular injury, and sometimes tongue lacerations. These must be addressed, but their treatment is of lower priority when TBI or skull fracture is present.

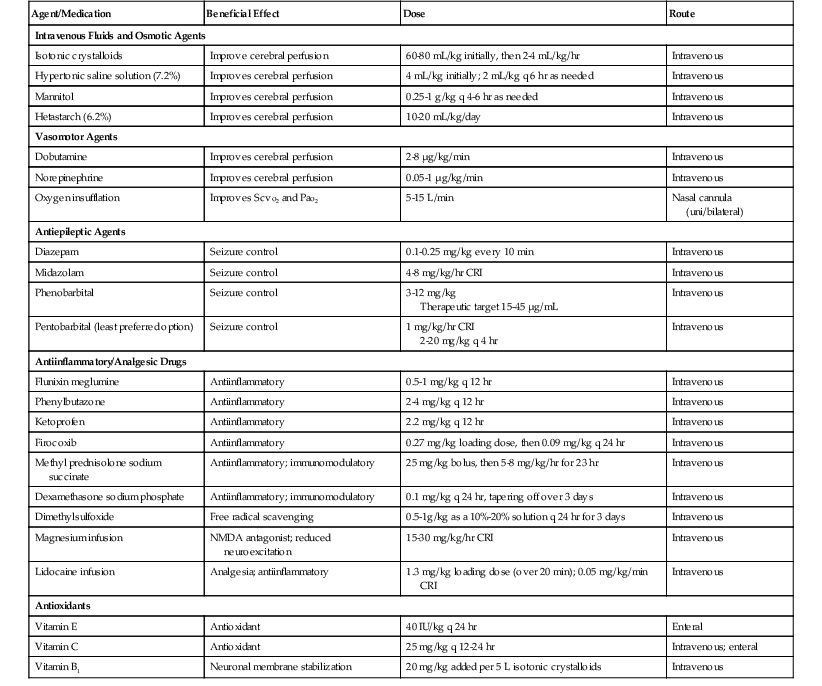

Limited evidence-based recommendations exist in the equine literature regarding appropriate management of TBI cases. Recommendations are therefore based on emergency treatment of human brain injury. Management and treatment goals for horses with traumatic head injury or TBI include implementing triage and preventing further damage; optimizing cerebral perfusion to ensure central nervous system (CNS) oxygen and metabolic substrate delivery, uptake, and utilization; stabilizing fractures; and attenuating secondary CNS injury. Commonly used drugs, dosages, and general comments related to their use are summarized in Table 9-1.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree