CHAPTER 35 Acne

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Acne is a disorder of follicular keratinization and is a well-recognized skin disease pattern in the cat.1,2 The etiopathogenesis of acne is not understood. Unproven causal factors have included changes in the hair growth cycle, poor grooming habits, stress, underlying seborrheic predisposition, abnormal sebum production, immunosuppression, and the effect of chronic viral infections.1,3 In human beings acne is a multifactorial disease of the pilosebaceous unit (sebaceous glands, hair follicles), and factors such as the alterations in the pattern of follicular keratinization, excessive sebum production, and hormonal imbalances are believed to play important roles. In contrast to human beings, acne is not confined to adolescence in cats.1,2,4 No breed predilections have been noted. There may be a gender predilection for neutered males.2

CLINICAL SIGNS

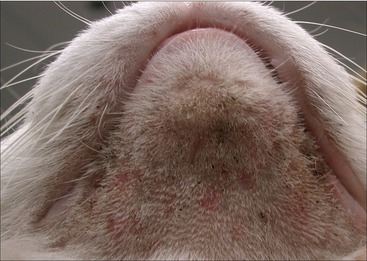

Mild, early cases of acne are characterized by the presence of comedones, scattered areas of dark crusts or keratinous debris, and mild alopecia (Figure 35-1). These lesions are located most commonly along the chin region, the lower lip, and occasionally the upper lip. At this stage most cats are asymptomatic. Some cats will remain in this comedonal stage and not progress to develop other signs. Other cats progressively begin to develop erythema, papules, pustules, alopecia, variable swelling, and pruritus (Figures 35-2 and 35-3). In more severe and chronic cases painful firm nodules will develop in conjunction with diffuse edema, thickening, fistulation, and eventual scarring (Figures 35-4 and 35-5).1,2,4 Regional lymphadenopathy also may be prominent. Some cats can have so much pain that lethargy and anorexia ensue.

DIAGNOSIS

Skin scrapings should be performed to rule out demodicosis. This may require sedation, depending on the degree of pain in the affected area. Cytological examination of the superficial skin and exudates should be performed to look for complicating bacterial and/or Malassezia infections. In cats with comedones, contents of the comedones should be examined cytologically; yeast organisms and/or demodectic mites may be found.1,2 These parasites can be primary or contributing causes. In addition, appropriate specimens should be collected for a fungal culture to rule out dermatophytosis. If furunculosis is present, cytological examination of exudates and tissue culture is indicated to identify primary and secondary bacterial or fungal infections. The most commonly isolated bacteria from acne lesions in cats are coagulase-positive staphylococci and alpha-hemolytic streptococci.2,3 Other organisms isolated less commonly include Micrococcus sp., Pasteurella multocida, and beta-hemolytic streptococci.2,3 In human beings, Propionibacterium acnes is the principal organism involved with inflammatory acne lesions.

Although the diagnosis of chin acne is relatively easy, identification of the underlying trigger may be more challenging. A thorough history and physical examination should be performed to look for an underlying cause. Often chin acne is a clinical sign of a whole-body skin disease. Some cats with underlying allergic skin disease (atopy, food hypersensitivity) will have the chin and perioral region involved as part of their pruritic distribution.1,2 An eosinophilic granuloma should be considered as a differential diagnosis for pronounced chin swelling; in these cats the chin is hard (Figure 35-6).1 Cats with chin edema also may have mastocytoma (Figure 35-7) (see Chapter 67). Chronic, refractory lesions should be biopsied and submitted for histopathological examination to determine the underlying cause (see the following section).

Outbreaks of acne in multiple-cat households have been reported and an infectious etiology has been suspected.2,4,5 In these cases differential diagnoses to consider include Demodex gatoi, dermatophytosis, viral infections (feline herpesvirus, feline calicivirus), and primary irritant contact dermatitis. A recent study demonstrated feline calicivirus antigen, via immunohistochemical staining from a cat with chronic acne, in a household of multiple cats with acne.2

HISTOPATHOLOGICAL FEATURES

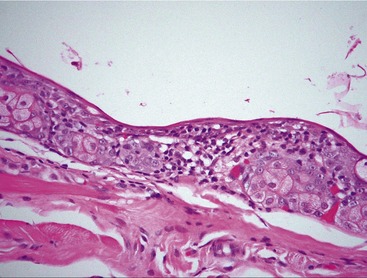

Discrete comedones represent ideal punch biopsy specimens. With early lesions the most common histopathological findings include lymphoplasmacytic periductal inflammation (Figure 35-8), sebaceous gland duct dilatation (Figure 35-9), and follicular keratosis with plugging and dilatation (Figures 35-10 and 35-11).2 Superficial hair follicles are distended with keratin to form comedones in patients in whom the cause is a follicular keratinization disorder. Attached sebaceous ducts commonly become distended with sebum. The epidermis may demonstrate mild acanthosis and spongiosis with some crusting. More advanced cases will demonstrate folliculitis (Figures 35-12 and 35-13), furunculosis, pyogranulomatous sebaceous adenitis and dermatitis, and epitrichial gland occlusion and dilatation (Figure 35-14).2,4 Staphylococcal organisms, as well as Malassezia spp. organisms, may be found in surface crusts and comedones. Cats with evidence of folliculitis and furunculosis commonly have secondary bacterial infections. With severe furunculosis, dermatophytosis may be a causative or complicating factor; special stains such as Gomori’s methenamine silver or periodic acid–Schiff can be used to aid in identification of the organisms. Special stains also may be needed for the identification of mast cell tumors/mastocytosis (see Chapter 67).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree