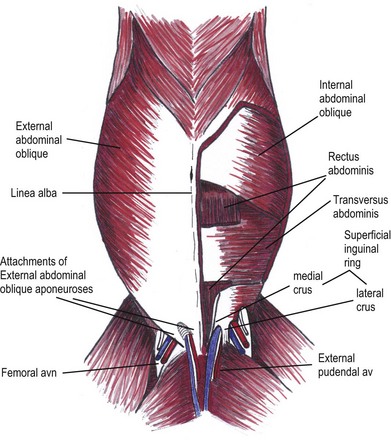

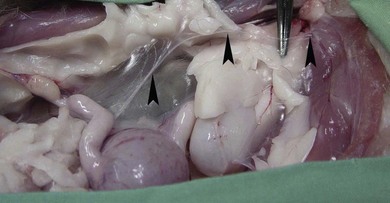

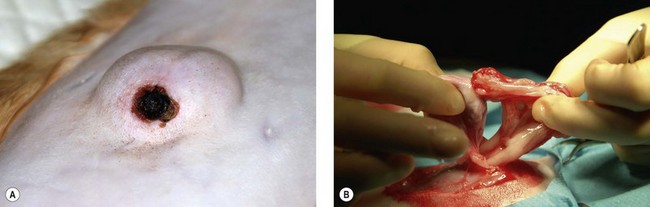

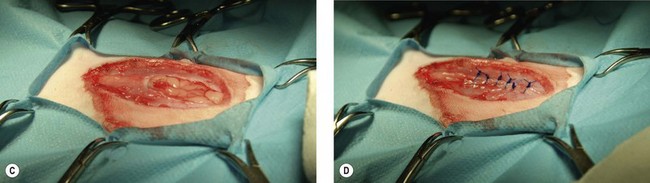

Chapter 25 The internal abdominal oblique (IAO) muscle arises predominantly from the tuber coxa, with smaller points of origin from the lateral crus of the EAO, thoracolumbar fascia and the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae. The fibers of the IAO run largely caudoventrally, and the central fascicles insert via an aponeurotic tendon to the linea alba after passing round the rectus abdominis. Towards the midline insertion there is usually some interchange of fibers between the aponeurosis of the IAO and EAO. The IAO has a free caudal margin, which is important with regard to the formation of the inguinal canal. In the dog, the cremaster muscle is formed from a caudal slip of muscle from the IAO, but in the cat the levator scroti muscle replaces the cremaster, which is absent. The levator scroti muscle is formed from fibers of the caudoventral border of the external anal sphincter and the pars caudalis of the external anal sphincter.3 The rectus abdominis (RA) is a broad band of muscle on either side of the linea alba that has a segmental appearance caused by irregular transverse septae. It takes its origin from the ventral surfaces of the rib cartilages and inserts at the pelvic brim via the strong prepubic tendon in dogs. It has been speculated that in cats the strong attachments of the crura of the superficial inguinal ring on the iliopubic eminence, plus the EAO muscle aponeurosis to the medial thigh may serve the same function as the prepubic tendon does in the dog.4,5 Despite the anatomic difference, it is standard practice to refer to a prepubic tendon in cats (Fig. 25-1). Figure 25-1 Cats do not have a structure that fits the precise description and appearance of the prepubic tendon in dogs. However, the strong attachments of the medial and lateral crura of the superficial inguinal ring on the iliopubic eminence, plus the external abdominal oblique (EAO) muscle aponeurosis to the medial thigh may serve the same function as the prepubic tendon does in the dog. The EAO is pictured excised on the right side of this diagram to show the relationship of the underlying rectus abdominis (RA) to the crura of the superficial inguinal ring and EAO aponeurosis. The location of the femoral artery and vein, and external pudendal artery and vein, are important to note from the point of view of surgery in this area. The inguinal canal is located adjacent to the groin, between the fleshy part of the IAO on one side and the lateral crus of the EAO on the other. Other than where the external pudendal vessels, the genitofemoral nerve, and the spermatic cord (male) or vaginal process (female) pass through the canal, it contains only fatty tissue. In male dogs the peritoneum evaginates through the inguinal canal, to form the vaginal tunic around the spermatic cord and testis while in the bitch it envelops the round ligament of the uterus and is called the vaginal process. Recent dissection of eleven embalmed adult female cats, however, failed to identify any evidence of either a vaginal ring or process.6 Similar anatomic information is not currently available in the literature for male cats; however, anatomic dissection of three male cadavers identified a consistent vaginal tunic, with no evidence of a vaginal process (personal communication, Joshua Milgram; also Fig. 25-2). Figure 25-2 The arrowheads in this figure show the line of the peritoneal sheet that covers the entrance to the inguinal canal in a female cat cadaver. There is no extension or pouch of peritoneum extending into the inguinal ring, and no visible vaginal process. (Courtesy of Joshua Milgram.) The perineum describes the part of the body wall that covers the pelvic outlet, and surrounds the anal and urogenital canals. The sacrotuberous ligaments in the dog form the lateral borders; cats, however, do not have a sacrotuberous ligament.3 The principal structure contained within the perineum is the pelvic diaphragm. This is a muscular structure consisting of the coccygeal and levator ani muscles, together with their internal and external fascial coverings. These muscles are anchored to the caudal vertebrae and pelvis. The ischiorectal fossa is a wedge-shaped depression formed between the external anal sphincter, levator ani and coccygeal muscles medially, the internal obturator muscle ventrally, and the superficial gluteal muscle laterally. The pudendal nerve and internal pudendal artery and vein pass into the fossa on the ventrolateral surface of the coccygeus before passing across the dorsal surface of the internal obturator muscle. The term hernia is used where the defect is congenital, due to a failure of embryonic signaling and fusion, and a distinct hernia ring and sac will exist. The term rupture is used where the defect is acquired, typically traumatically. Ruptures do not have a distinct hernia ring and sac. Therefore, although the terms ‘hernia’ and ‘rupture’ are not synonymous, for certain conditions they are used interchangeably, e.g., diaphragmatic hernia/diaphragmatic rupture, or perineal hernia/perineal rupture. In this chapter the term hernia will be used, although the reader should understand that this also includes ruptures (Table 25-1). Table 25-1 Definition of common terms used in relation to hernias Further comments specific to each type of abdominal hernia follow later in this chapter. Laboratory tests will not specifically diagnose the presence of a hernia, but they may form an important part of assessment and planning or provide a baseline against which to assess postoperative progress. The extent of testing required preoperatively will obviously depend both on the patient and the presenting complaint. A young animal in good health undergoing an elective surgery will require less testing than one due to undergo a more complex procedure, or an emergency procedure.7 For patients with uncomplicated, small, reducible hernias, routine abdominal imaging is unlikely to be of significant benefit unless there is a specific indication, e.g., checking for peritoneopericardial hernia with a supraumbilical defect. If the history and/or physical examination are suspicious for entrapment or strangulation of organs within hernia sacs, then ultrasound examination is most likely to be helpful. Plain and contrast radiography may be useful in specific cases, such as where bladder involvement is suspected (Fig. 25-3). Where traumatic body wall ruptures are encountered, further imaging is always warranted to investigate not only the abdominal injury but also concurrent pathologies such as possible pulmonary contusions, pneumothorax or orthopedic injuries. Advanced imaging modalities such as CT or MRI can provide excellent levels of detail, and a CT scan is strongly recommended for investigation of traumatic abdominal wall hernias in humans.8 These modalities are unlikely to be necessary for routine investigation of abdominal hernias in veterinary patients unless the hernia is traumatic and concurrent neurological injury is suspected. Figure 25-3 Plain and contrast radiography can be useful for identifying specific injuries. (A) In this case the plain films show loss of the ventral abdominal wall line with loops of small intestine outside the normal confines of the body wall. (B) The ruptured bladder/urethra is not, however, evident without administration of contrast. These are usually congenital, and are often identified as inconsequential findings during routine pre-vaccination examination. The abdominal wall develops from migration of the cephalic, caudal and lateral folds, with the umbilical aperture remaining as a normal defect after migration and fusion of the folds.8 Umbilical vessels, the vitelline duct, and the stalk of the allantois pass through this umbilical ring in the fetus, but the opening should close at birth, leaving the umbilical cicatrix. If the aperture fails to contract, is excessively large or improperly formed, then a hernia may result. Umbilical hernias are usually congenital and are thought to be inherited. The Cornish Rex breed is listed as over-represented for umbilical hernias although this is largely based on a high incidence that was reported within one family.9 Umbilical hernias should not be confused with congenital cranial abdominal hernias or supraumbilical hernias, which can be associated with peritoneopericardial hernia. Two reports have documented the incidence of congenital hernias per 1000 cats as between 1.43–1.66 (umbilical) and 0.25–0.2 (inguinal);10,11 however, these reports reflect the hospital population in the US and Canada in the early 1970s and may not be generally applicable. Acquired umbilical hernias may result from excessive traction during assisted parturition, or from clamping and severing the umbilical vessels too close to the body wall. Omphaloceles are large midline umbilical and skin defects that result in evisceration of abdominal organs. Most affected neonates either die or are euthanized at birth. Attempted repair has been reported in a litter of five-day-old kittens; however, treatment was unsuccessful as the abdominal wall was too thin and fragile to hold sutures.12 Gastroschisis (this is a congenital defect characterized by a defect in the abdominal wall through which the abdominal contents freely protrude) may appear similar to an omphalocele, but the condition is paramedian rather than midline. It has been reported only rarely in cats, and typically results in early neonatal death.13 Umbilical hernias are usually identified soon after birth, unless the defect is very small. A very small hernia ring that contains only falciform fat is unlikely to cause major problems in the short term, allowing repair to be postponed until the patient is older (Fig. 25-4). If, however, the defect is large enough to allow herniation of intestinal loops or this is already happening then the hernia should be addressed regardless of age. In dogs there is a known association between umbilical hernia and cryptorchidism; similar information is not available for cats but the presence of other concurrent congenital anomalies should be carefully evaluated as these may affect prognosis as well as an owner’s willingness to treat. Figure 25-4 (A) A large umbilical hernia in an adult cat that developed an area of ulceration on the most ventral aspect of the swelling. (B) Adhesions were present between the ulcerated area and the falciform fat. (C) The hernia was resected and (D) closed with simple interrupted sutures of polydioxanone. It is recommended not to correct umbilical hernias in puppies less than 6 months of age as there is potential for delayed closure up to this time; no similar recommendations are available for kittens.14 The surgical technique is described in Box 25-1.

Abdominal wall hernias and ruptures

Surgical anatomy

Abdominal wall1,2

Pelvic diaphragm1–3

Classification of hernias and ruptures

Term

Comments

Hernia

Protrusion of an organ, in whole or in part through a defect in the wall of the anatomical cavity within which it normally lies. The terms ‘hernia’ and ‘rupture’ are not synonymous, although for certain conditions they are used interchangeably e.g., diaphragmatic hernia/diaphragmatic rupture or perineal hernia/perineal rupture

True hernia

Consists of a hernia ring/defect and a hernia sac, which contains the hernia contents

False hernia

Does not necessarily imply the presence of either a hernia ring or sac

Hernia defect or ring

This may be a normal opening such as the inguinal ring; an iatrogenic opening such as with incisional hernia; or an abnormal defect as in prepubic tendon avulsion

Hernia sac

This is a thin serosal lining surrounding and covering the contents of the hernia. In the case of abdominal hernias this lining will be peritoneum. There may be additional layers of muscle, fascia and skin outside the hernia sac depending on the location and type of hernia

Incisional hernia

This occurs when surgical closure of any body cavity fails or disrupts

Diagnosis and general considerations

Physical examination

Laboratory tests

Diagnostic imaging

Umbilical hernias

Physical findings

Treatment and surgical techniques

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine