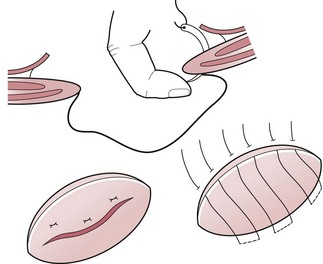

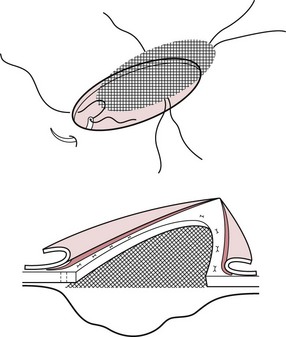

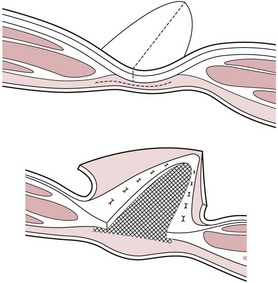

Chapter 4 An external hernia occurs through the body wall producing a visible and palpable swelling covered by skin, whereas an internal hernia occurs within the abdominal cavity (Box 4.1). Umbilical hernias may be oval in shape and vary in size from one to several centimetres in diameter. The sutures are inserted 1–2 cm from the margin of the ring and are carried through the full thickness of the abdominal wall on both sides of the ring. A finger inserted into the inverted sac serves to guide the needle and prevent inadvertent damage to the intestine (Figure 4.1). The ends of each suture are held with haemostats until they are all in place. Simultaneous traction on the sutures overlap the edges of the ring and this is maintained while each individual suture is tied. The subcutaneous tissue is apposed with a continuous suture of polyglactin, and the skin with a subcuticular suture of the same material. The application of an elastic bandage encircling the abdomen (or a stent bandage in the case of small hernias) will provide protection from contamination and eliminate dead space. The mesh is best placed in an extraperitoneal position between the internal rectus abdominal sheath and the peritoneum. The peritoneal sac is dissected down to the hernial ring and inverted into the abdominal cavity as described above. If the sac is sufficiently large, the mesh can be placed within it (Figure 4.2), but if it is not, the peritoneum is reflected peripherally from the deep fascial sheath of the rectus abdominis muscle for 1–3 cm to create a space for the mesh. The mesh is cut so that it overlaps the margin of the ring by the same amount. The sutures are preplaced before tying. Sufficient tension is applied so that the mesh is kept taut and flat. The subcutaneous tissues and skin are then carefully apposed over the mesh. Diagnosis: Signs of depression, abdominal discomfort and cessation of defecation indicate intestinal obstruction requiring prompt intervention. Treatment: When intestinal obstruction necessitates immediate surgery, the tissues surrounding the rent or hernia are very friable and have little suture holding power. It is not uncommon for disruption of the surgical repair to occur during recovery from anaesthesia. Therefore, when the hernia is not accompanied by signs of intestinal obstruction, it is advisable to delay surgery for 3–6 weeks until swelling has subsided and deposition of collagen has increased the tensile strength of the damaged tissues. The defect is closed by suturing each layer in turn. Forceful approximation of the edges of a large fascial defect inevitably leads to failure. To repair large hernias a mesh prosthesis is required. Since the margin of the defect is less well defined than in umbilical hernias, it is necessary to dissect the peritoneum from the inner sheath of the rectus to create an adequate ‘shelf’ to support the mesh (Figure 4.3). Alternatively, a mesh inlay graft with the onlay apposition of supportive hernial sac fascia can be used (Figure 4.4).

Abdominal cavity

4.1 Hernias

Umbilical hernias

Open reduction

Ventral hernias

Incisional hernias

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Abdominal cavity