Chapter 6 THE ABDOMEN

The symmetry, size and shape of the abdomen varies considerably from breed to breed. In the bitch, the mammary glands are an important pre- and post-natal feature and in the pregnant bitch the topography may be altered and caesarean section required. This is carried out as for any abdominal laparotomy described below.

Other abdominal diagnostic techniques include liver biopsy. This used to be done from the left side of the abdomen to avoid damage to the right-sided gall bladder, large vessels and bile ducts at the hilus of the liver, i.e. dog is in right lateral recumbency after fasting, as it is not easy with a full stomach. To take just liver cells, it is possible to carry out a fine-needle biopsy in the 10th intercostal space on the right hand side, at the level of the costochondral junction. Nowadays, many surgeons tend to do this using ultrasound or laparoscope.

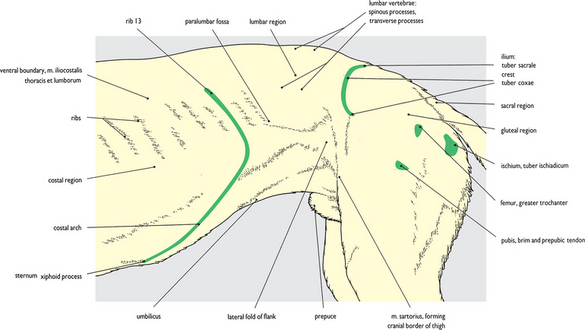

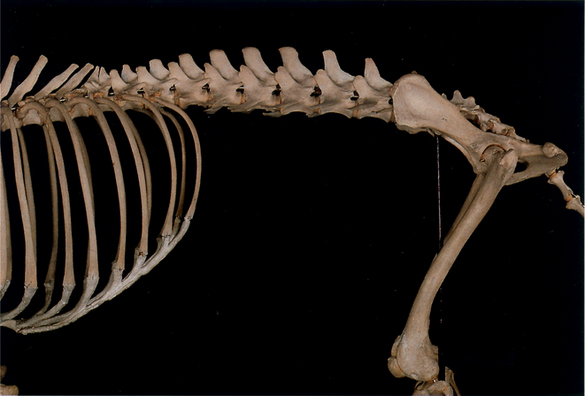

Fig. 6.1 Surface features of the abdomen and hip: left lateral view. The bony ‘landmarks’ that are palpable around the borders of the abdomen are shown in this figure. In a normal standing position the femur and its covering thigh muscles obscure the rear end of the abdomen. The caudal border of the abdomen is marked by the tuber coxae dorsolaterally and the pubis ventrally. The inguinal ligament, marking the caudal border of the muscular abdominal wall, is palpable between these two points in the fold of the groin (see also Fig. 6.67 of the abdomen in ventral view).

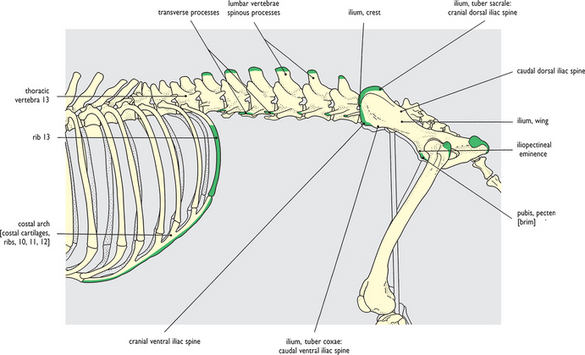

Fig. 6.2 Skeleton related to the abdomen: left lateral view. The palpable bony features shown bordering the abdomen in the surface view on Fig. 6.1 are colored green for reference. It should be noted that caudal to the large thoracic outlet (bounded by the xiphoid cartilage of the sternum, the costal arches and floating ribs) the abdominal wall is entirely muscular. The considerably restricted pelvic inlet, bounded by the sacrum above and pelvic bones bilaterally, marks the caudal boundary of the abdomen.

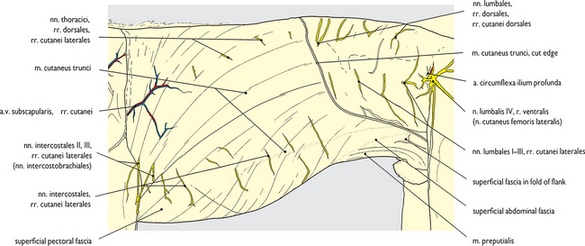

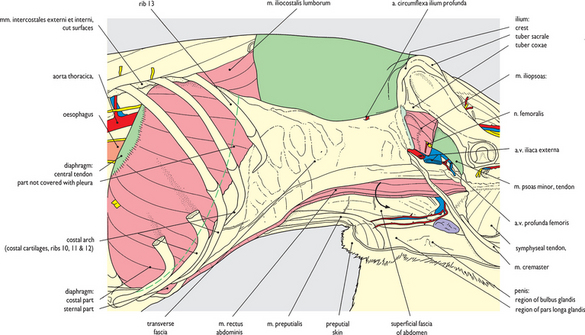

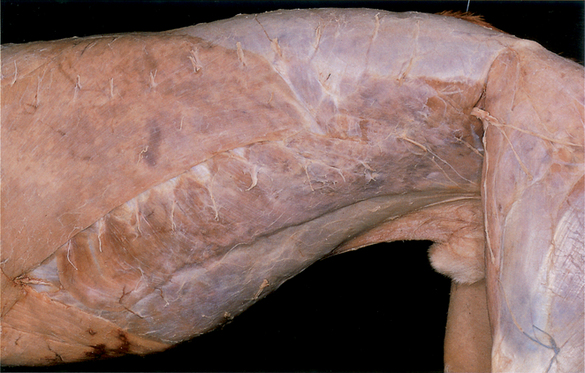

Fig. 6.13 Superficial structures of the abdomen – cutaneous nerves: left lateral view. The remaining superficial fascia has been cleaned from the trunk along with most of the cutaneous muscle. On the underside of the abdominal wall the glans of the penis and its enclosing prepuce are suspended by a fold of skin. This fold has been removed from the left side exposing the preputial muscle radiating caudally into the prepuce, and the preputial components of the external pudendal vessels extending cranially from the inguinal region (see also Figs 6.14, 6.46 and 6.101).

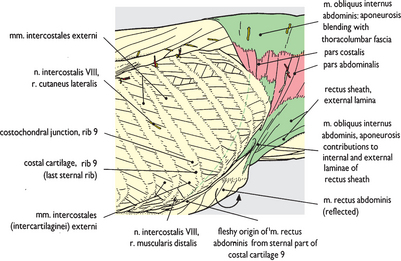

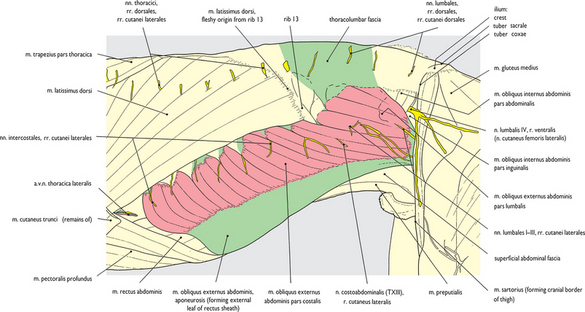

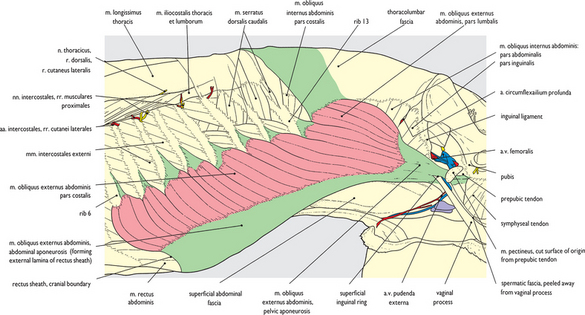

Fig. 6.14 Abdominal wall (1). External abdominal oblique muscle after removal of the hindlimb: left lateral view. Removal of the left hindlimb exposes the overall extent of the muscular abdominal wall. The latissimus dorsi and pectoral muscles have also been removed from the thorax which exposes the origin of the external oblique muscle. The caudal limit of the muscular abdominal wall, the inguinal ligament, is visible on the surface of the iliopsoas muscle. Ventrally the aponeurosis of the external oblique forms a major component of the external layer of the rectus sheath (see also Figs 6.69–6.71).

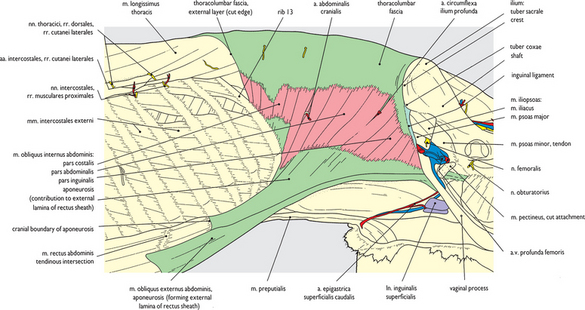

Fig. 6.15 Abdominal wall (2). Internal abdominal oblique muscle: left lateral view. The external oblique has been removed except where it forms part of the external layer of the rectus sheath. Here it is inseparable from the underlying aponeurosis of the internal oblique (see also Figs 6.69–6.71). The pelvic tendon of the external oblique has also been removed, in consequence the inguinal canal is completely opened on its cranial and lateral aspects. Cranially the contribution of the aponeurosis of the internal oblique to both deep and superficial layers of the rectus sheath is exposed. This relationship is shown to advantage in the next few figures and in Figs 5.16–5.19.

Fig. 6.19 Abdominal wall (6). Rectus abdominis muscle and rectus sheath external layer: left lateral view. The internal oblique muscle has been almost completely removed. Only the ventral part of its aponeurosis remains on the surface of the rectus abdominis muscle where it forms the external layer of the rectus sheath together with the aponeurosis of the external oblique. The two are inseparably fused down to the linea alba in the midventral line. The rudimentary rib 14 has been removed and the series of nerves entering the upper part of the abdominal wall are displayed on the surface of the transverse muscle (see also Fig. 6.72).

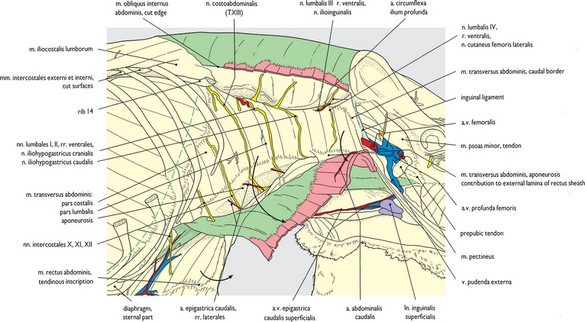

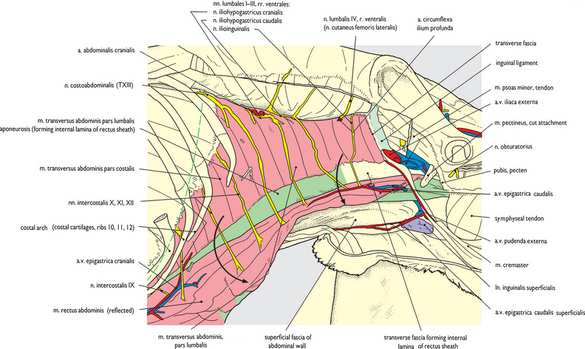

Fig. 6.20 Abdominal wall (7). Rectus abdominis muscle and rectus sheath internal layer: left lateral view. Severing of the caudal part of the transverse abdominal aponeurosis where it contributed to the external layer of the rectus sheath has allowed the rectus abdominis muscle to be reflected ventrally away from the underlying transverse muscle and aponeurosis. The dorsal surface of the rectus is exposed with the terminations of abdominal wall nerves entering it in series. The internal layer of the rectus sheath is represented here by the aponeurosis of the transverse muscle, except caudal to the caudal iliohypogastric nerve branch where it consists solely of transverse fascia (see also Figs 6.72 and 6.101).

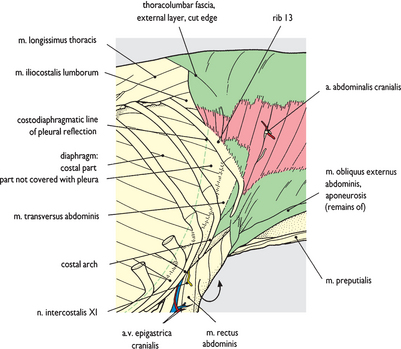

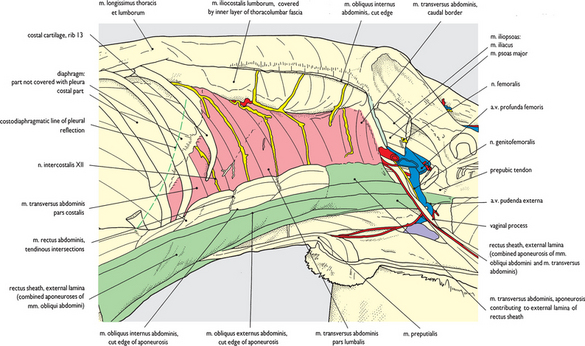

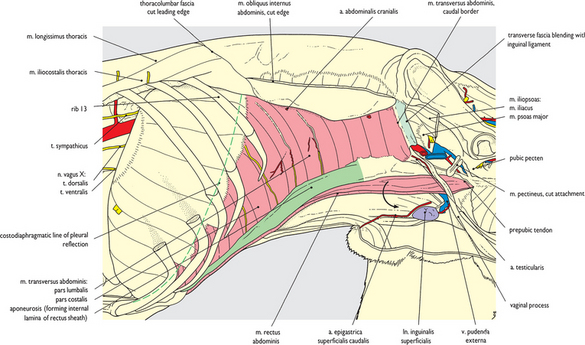

Fig. 6.21 Abdominal wall (8). Transverse abdominal muscle and diaphragm: left lateral view. The transverse abdominal muscle is exposed in its entirety after removal of the rectus abdominis muscle and the nerves of the abdominal wall. The costal part is seen arising from the internal face of the costal arch interdigitating with fibers of the diaphragm immediately caudal to the costodiaphragmatic line of pleural reflection. The lumbar part emerges from beneath the iliocostalis lumborum. The extensive aponeurosis ventrally provides the internal lamina of the rectus sheath and extends down to the linea alba (see also Figs 6.70, 6.72). The caudal border of the transverse muscle does not extend to the caudal end of the abdominal wall.

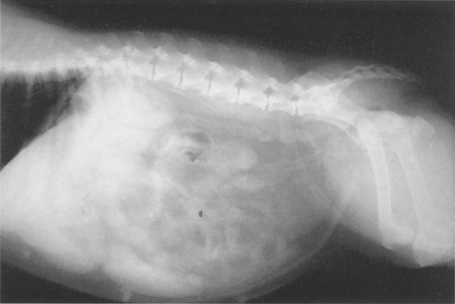

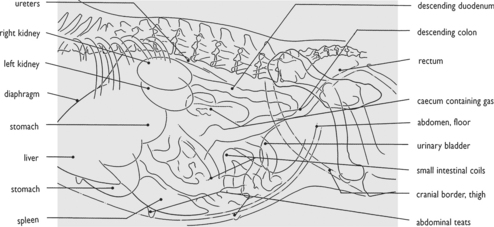

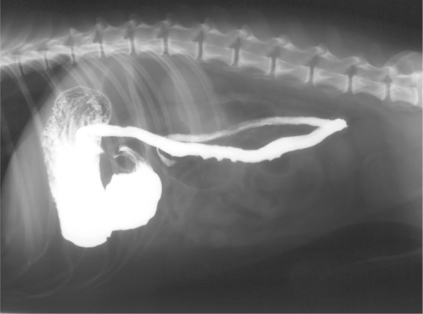

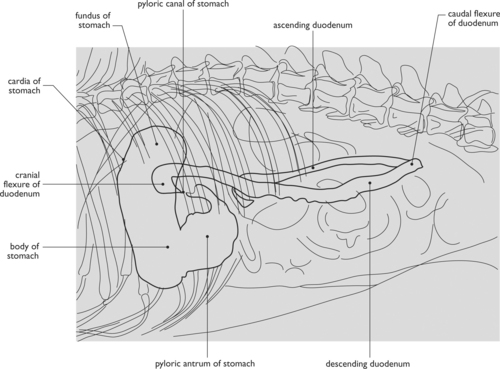

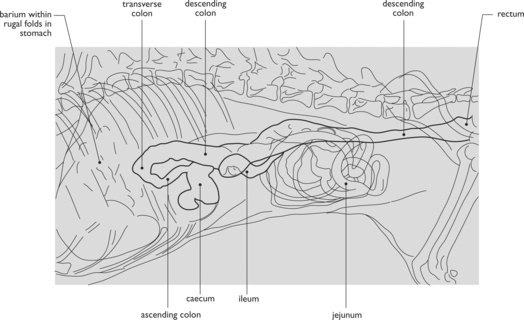

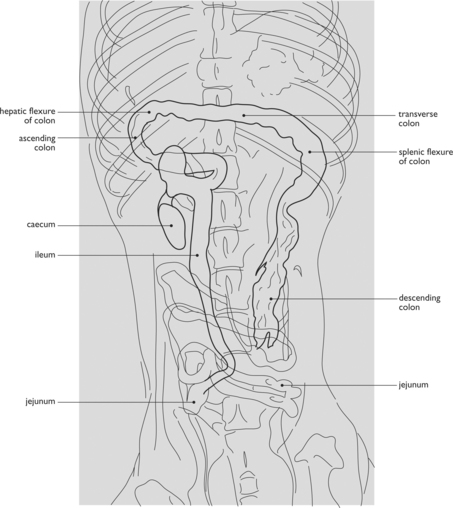

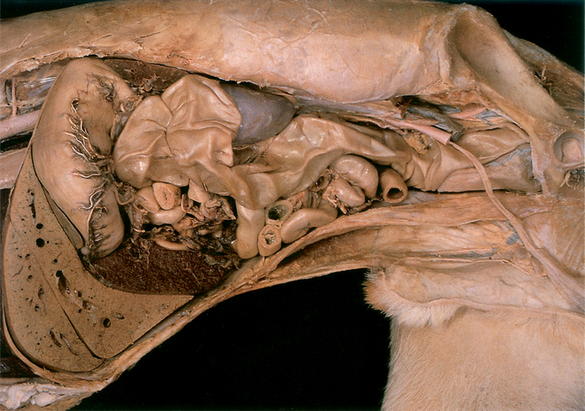

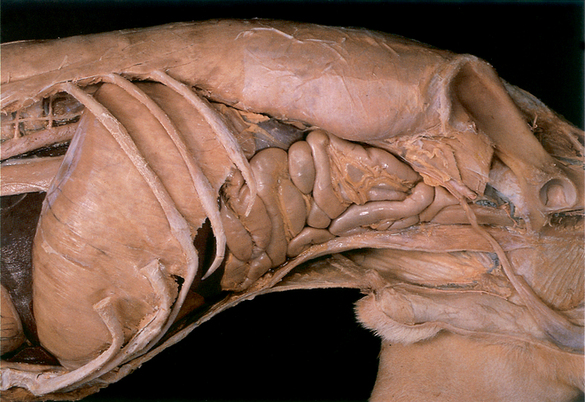

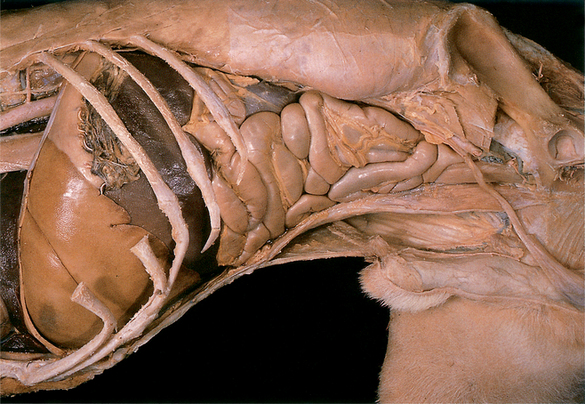

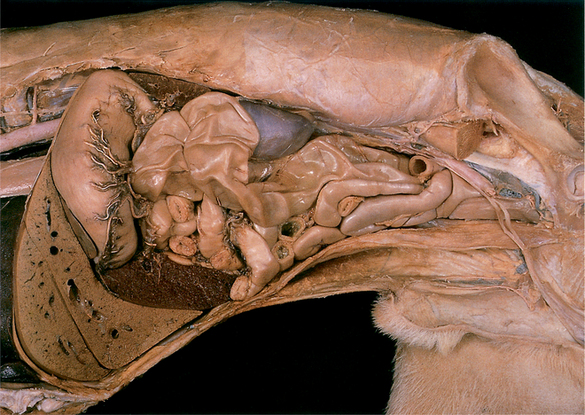

Fig. 6.23 Abdominal viscera in situ (1). After removal of the abdominal wall: left lateral view. Removal of the transverse fascia and the closely applied parietal peritoneum opens the peritoneal cavity and exposes jejunal coils. Several areas where fat is deposited beneath the peritoneum are apparent; viz. great mesentery associated with the jejunal coils, around the kidney (perirenal fat), and in the falciform ligament ventrally (see also Figs 6.74 and 6.75 for fat deposits in the abdomen). Also visible in the great mesentery are clearly defined opaque strips which represent afferent lymphatic channels. Compare this view with equivalent views from the right (Fig. 6.47) and ventrally (Fig. 6.73).

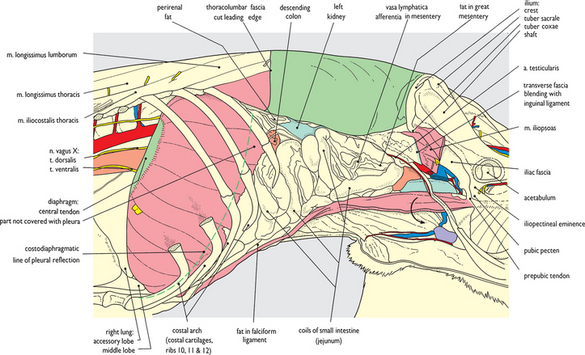

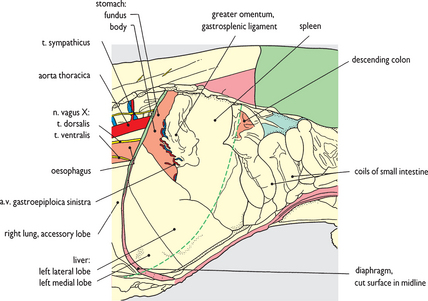

Fig. 6.24 Abdominal viscera in situ (2). After removal of the abdominal wall and diaphragm: left lateral view. The left half of the diaphragm has been removed, the cut edge of the diaphragmatic cupola in the midline now indicates the most cranial extent of the abdominal cavity. The costal arch is left in place and the position of the costodiaphragmatic line of pleural reflection is still indicated by the broken line in advance of it. Compare this view with equivalent views from the right side (Fig. 6.48) and ventrally (Fig. 6.76).

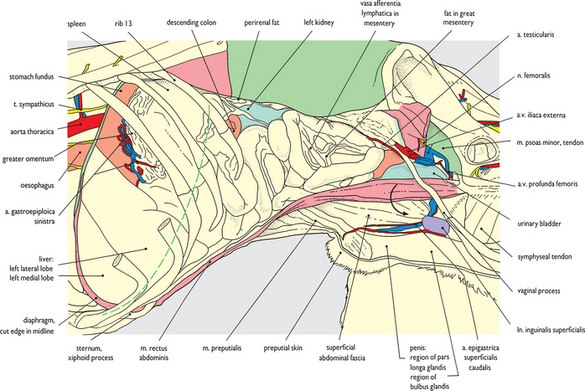

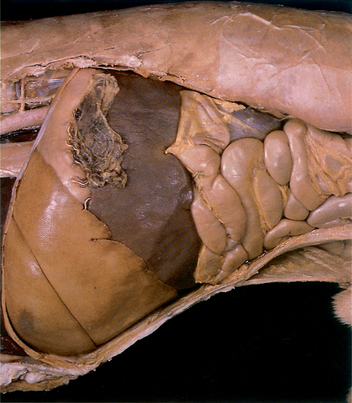

Fig. 6.25 Viscera of the cranial abdomen in situ after removal of the abdominal wall, ribs and diaphragm: left lateral view. At the cranial end of the abdomen the remaining ribs and costal arch have been removed. The spleen is abnormally enlarged following barbiturate narcosis, and extends right down to the belly floor in the xiphoid region (see also Figs 6.77, 6.78 in ventral view, Figs 6.88–6.90 in caudal view, and Figs 6.96, 6.97 in section).

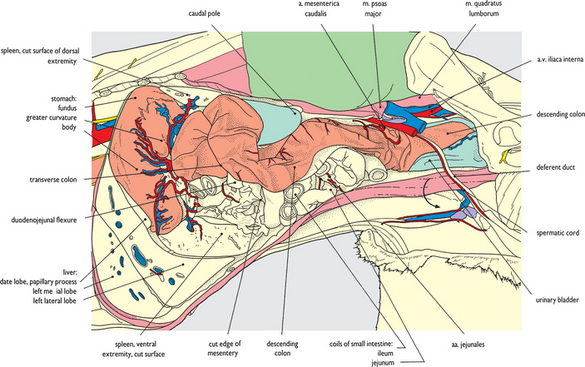

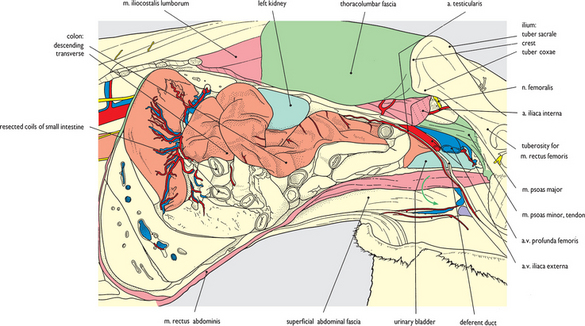

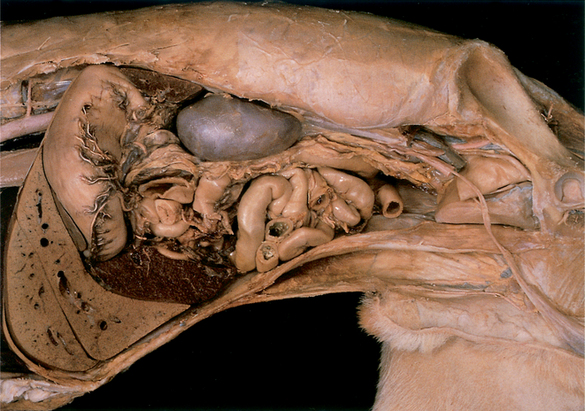

Fig. 6.26 Descending colon: left lateral view (1). The transverse and much of the descending part of the colon have been exposed following removal of the deep layer of the greater omentum and a number of jejunal coils. The colon in this specimen is somewhat enlarged and appears sacculated. For a more ‘normal’ appearance see Fig. 6.61 from a right medial view and Figs 6.80 and 6.82 from a ventral view. Dorsal to the colon the left kidney is exposed further by removal of perirenal fat. In the caudal abdomen the iliacus component of the iliopsoas muscle has been removed, and the psoas major has been additionally trimmed as far cranially as the tuber coxae.

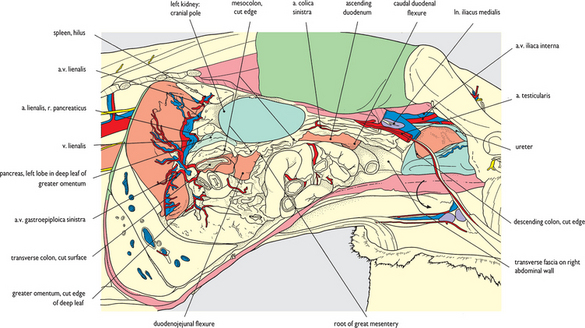

Fig. 6.28 Left kidney and mesocolon: left lateral view. The descending colon has been removed except for its terminal part dorsal to the bladder. Cranially, the cut surface of the transverse colon is clearly observed immediately cranial to the duodenojejunal flexure (its position is shown to advantage in section in Fig. 6.97). Extending caudally from the transverse colon, below the kidney, the fat infiltrated mesocolon and its cut edge are visible. Medial to the duodenojejunal flexure and caudal to the transverse colon the mesenteric root is just exposed. The relationship of structures to the root is shown to advantage in ventral view (Figs 6.80, 6.81) and in section (Figs 6.98, 6.99).