CHAPTER 7. Necropsy Techniques

Jon S. Patterson

EXTERNAL EXAMINATION

I. Before beginning the necropsy:

A. Obtain a body weight on the animal

B. Record any identification numbers (e.g., ear tags, tattoos)

II. Note any external abnormalities

A. Cutaneous abrasions, lacerations, hemorrhages, masses

B. Areas of acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, excessive pigmentation (melanosis) or hypopigmentation

C. Areas of inflammation or crusting in unpigmented areas of skin (e.g., photosensitive dermatitis)

D. Interdigital inflammation, ulcers, pustules, blisters

E. External parasites (fleas, mites, ticks, lice)

F. Nasal, ocular, vulvar, penile discharges

G. Diarrhea

H. Exudate in external ear canals

I. Dental tartar, gingivitis, oral ulcers

J. Subcutaneous edema

1. Dependent edema (ventral neck, limbs)

2. Pitting edema

III. Note the body condition of the animal

A. Thin, emaciated, obese

B. Body-condition scoring system may be used

C. Dehydration: Measured postmortem by degree of withdrawal of eyes into orbits

D. Mucous membranes

1. Pale: Anemia

2. Bluish or purplish: Cyanosis

3. Dark red: Injected, “toxic”

EXAMINATION OF THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM

I. Gross examination of skeletal muscle

A. Volume

1. Atrophy or hypertrophy

2. Assess symmetry, right vs. left side

B. Color

1. Pale (lighter brown than normal, tan, or white)

a. Degeneration or necrosis

b. May indicate streaks of adipose tissue

2. Darker red brown than normal

a. Myoglobin staining (from extensive necrosis)

b. Hemorrhage or inflammation

3. Focal discolorations associated with injected medications

C. Texture

1. Gelatinous: Edema, degeneration, necrosis

2. Chalky, firm, gritty areas

a. Dystrophic calcification

b. Nutritional myopathy (vitamin E or selenium deficiency)

3. Soft, friable: Inflammation, necrosis

D. Postmortem changes

1. Rigor mortis: Stiffening of the muscles

a. Occurs 2 to 4 hours after death and lasts 1 to 2 days

b. Time of onset depends on muscle activity, nutritional status, and body and environmental temperature at time of death

c. Rigor begins in myocardium, then progresses to skeletal muscles of the head and neck and then to extremities

2. Muscle relaxation occurs after rigor as muscle protein begins to degrade

II. Gross examination of bones

A. Routine necropsy includes examination of at least one long bone and two to three joints. Cut a long bone (e.g., femur) longitudinally

1. Assess diaphyseal bone marrow fat stores

a. Normally opaque white to tan in adults

b. Serous atrophy of fat: Gelatinous

2. Assess hematopoietic activity. Red areas indicate active hematopoiesis

3. Assess thickness of cortical bone, amount and distribution of cancellous or trabecular bone

4. Assess thickness and uniformity of metaphyseal growth plates in growing animals

B. Joints examined typically include the following:

1. Coxofemoral

2. Tibiotarsal-tarsometatarsal

3. Radiocarpal-carpometacarpal

C. Assess articular cartilaginous surfaces

1. Erosions, ulcers

2. Cracks or fissures

3. Periarticular bony proliferation (osteophytes)

D. Assess quality and volume of joint fluid

1. Normal: Viscous, stringy, clear

2. Fibrin: Suggests inflammation, possibly septicemia

3. Watery or cloudy: Suggests inflammation or infection

E. Fractures. Often associated with subcutaneous or intramuscular hemorrhage, edema, or tissue necrosis

G. Assess degree of ossification or calcification of long bones or ribs by digital pressure

1. Normal rib should snap under digital pressure

2. Rib with osteoid or calcium deficiency (i.e., metabolic bone disease) will bend extensively before it breaks (rubbery consistency, if severe)

H. Serous atrophy of diaphyseal bone marrow fat

1. Best appreciated in long bones, such as femur

2. Other sites of serous fat atrophy include epicardium, pericardium, perirenal fat, mesentery, and omentum

III. Some common myopathies

A. Clostridial myositis (“blackleg”): Clostridium chauvoei. Beef cattle, dairy cattle

B. Arcanobacterium pyogenes abscesses: Cattle

C. Sarcocystosis (protozoal myopathy)

1. Cattle

2. Usually an incidental finding, detectible only histologically

3. If severe, there may be grossly appreciable tan foci in muscle

D. Nutritional myopathy: Vitamin E or selenium deficiency → myodegeneration, necrosis

E. Malignant hyperthermia

1. “Porcine stress syndrome”

2. Genetic predisposition in certain strains of swine

IV. Some common bone diseases

A. Rickets

1. Defective endochondral ossification in growing animals

2. Bone deformities and pathologic fractures

3. Thickened growth plates that fail to mineralize

4. Vitamin D, calcium, or phosphorus deficiency

B. Osteomalacia

1. Softening or weakening of bone in adult animals

2. Vitamin D or phosphorus deficiency, chronic renal disease, or chronic fluorosis

C. Fibrous osteodystrophy: Resorption of bone and replacement by fibrous tissue associated with primary, secondary, or pseudohyperparathyroidism

D. Osteosarcoma

1. Arise most commonly at metaphyses of distal radius, distal tibia, and proximal humerus

2. Most common in mature large- and giant-breed dogs

E. Degenerative joint disease

1. Articular erosions, ulcers, osteophytes

2. Age-related or secondary to other primary bone disease (e.g., cervical vertebral malformation-malarticulation)

F. Intervertebral disc disease

1. “Chondroid degeneration” of discs in chondrodystrophic breeds of dogs

2. “Fibrous degeneration” of discs in nonchondrodystrophic breeds

EXAMINATION OF THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

I. Gross examination of the thoracic cavity

A. Puncture diaphragm from abdominal cavity to assess negative pressure in thorax

1. Perceivable inrush of air to thorax and billowing of diaphragm toward abdomen if animal has been dead less than a few hours

2. Lack of this movement may indicate pneumothorax, pleural effusion, or noncollapsible lungs owing to pulmonary edema, pneumonia, fibrosis, or emphysema

B. Rib cage

1. Fibrinous adhesions between visceral and parietal pleura indicate acute pleuritis

2. Fibrous adhesions between visceral and parietal pleura indicate chronic pleuritis or healed lesions from previous pleuritis

3. Check for rib fractures

C. Tongue, pharynx, larynx, trachea, bronchi, lungs, and heart are removed as one (“pluck”), and examined outside of the animal

D. Estimate volume of fluid, if any, in thoracic cavity. A small volume of serous fluid is normal

II. Nasal cavities

A. Turbinate atrophy (e.g., atrophic rhinitis of swine [ Pasteurella multocida type D])

B. Catarrhal rhinitis

1. Increased volume of mucous exudates

2. Bacterial or viral causes or implies relatively mild inflammation

C. Suppurative rhinitis: Bacterial causes are most likely

D. Granulomatous rhinitis

1. Thick, less fluid exudate or no grossly visible exudates

2. Chronic

3. May be thickening of mucosal lining or polypoid nodules

4. Fungi, higher bacteria, foreign bodies

III. Sinuses

A. Sinusitis often occurs in combination with rhinitis. May be a sequela to septic wound (e.g., dehorning in cattle, tooth infection in horses and dogs)

B. Chronic sinusitis may extend into adjacent bone (osteomyelitis) or cribriform plate to cranial cavity (leading to meningitis or encephalitis)

C. Common causes of rhinitis and sinusitis

1. Horses

a. Equine herpesvirus (EHV-1 and EHV-4)

b. Equine influenza virus

c. Equine adenovirus (especially severe in Arabian foals with combined immunodeficiency)

2. Cattle

a. Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus (BHV-1). Pseudomembranous or fibrinonecrotic

b. Malignant catarrhal fever (bovine herpesvirus-2 outside of Africa). Ocular and nervous system inflammation as well

3. Swine

a. Atrophic rhinitis ( Pasturella multocida type D)

b. Inclusion body rhinitis (cytomegalovirus, a herpesvirus)

4. Dogs

a. Canine distemper virus, canine adenovirus types 1 and 2, parainfluenzavirus

b. Bordetella bronchiseptica, P. multocida, Escherichia coli

c. Aspergillus spp., Cryptococcus neoformans, Rhinosporidium seeberi

5. Cats

a. Feline viral rhinotracheitis (FVR; herpesvirus-1), feline calicivirus

b. Chlamydia felis. Also conjunctivitis

c. Mycoplasma felis. Also conjunctivitis

d. Cryptococcus neoformans

IV. Pharynx, larynx, and trachea

A. Anomalies

1. Brachycephalic airway syndrome (dogs)

a. Stenotic nares, elongated soft palate

b. Secondary nasal and laryngeal edema

2. Dorsal displacement of soft palate in horses. Hypoplastic epiglottis prone to entrapment

3. Tracheal or tracheobronchial collapse

a. Toy and miniature breed dogs

b. Dorsoventral flattening of trachea, with wide dorsal membrane

B. Laryngeal hemiplegia of horses

1. Idiopathic, traumatic, or inflammatory injury to left recurrent laryngeal nerve

2. Muscle atrophy of dorsal and lateral cricoarytenoideus muscles

C. Inflammation

1. Redness

2. Fibrinous or suppurative exudate

3. May obstruct airflow or lead to secondary bronchopneumonia

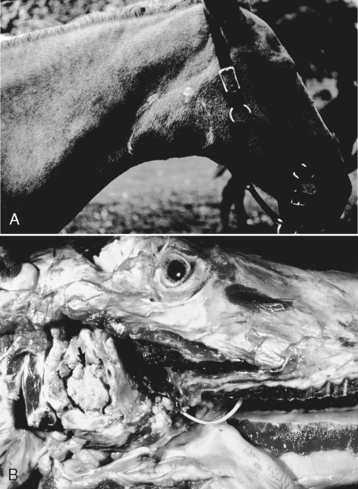

4. Guttural pouch inflammation in horses (Figure 7-1)

|

| Figure 7-1 Guttural pouch empyema, guttural pouch, horse. A, Note the swollen right neck (outlined) in this horse with guttural pouch empyema. B, The guttural pouch is filled with masses of inspissated purulent exudate (arrow). ( A, Courtesy College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Illinois. B, Courtesy Dr. M.D. McGavin, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tennessee.) |

a. Aspergillus spp.

b. Usually unilateral

c. Erosion into internal carotid artery may lead to epistaxis

d. Empyema of guttural pouches may be a sequela to suppurative rhinitis, most commonly caused by Streptococcus equi

5. Necrotic laryngitis (“calf diphtheria”)

a. Pseudomembranous

b. Fusobacterium necrophorum infection

6. Canine infectious tracheobronchitis (“kennel cough”). Bordetella bronchiseptica, canine adenovirus 2 or canine parainfluenzavirus

D. White, foamy fluid in upper respiratory tract suggests pulmonary edema

E. Free fibrin or suppurative exudate in the absence of redness or a pseudomembrane suggests inflammation from lower respiratory tract

V. Tracheobronchial lymph nodes

A. Red and wet suggest acute inflammation

B. White or tan foci suggest necrosis, inflammation, or lymphoid hyperplasia

VI. Lungs

A. Texture or consistency is the most important feature to evaluate

1. Spongy: Normal. Implies lung is adequately aerated

2. Rubbery

a. Atelectasis (i.e., not adequately inflated, aerated, or expanded). Determine whether a newborn animal found dead took a breath by immersing a piece of lung tissue in water or fixative

(1) If it floats, the animal took a breath

(2) If it sinks, the animal was stillborn

b. Fetal lungs should be atelectatic

c. Congested lungs may be slightly rubbery. Diffusely red, ooze blood on cut section

d. Edematous lungs may be rubbery. Ooze watery or foamy fluid on cut section

3. Firm or consolidated

a. Implies compromise of alveolar spaces

(1) Exudate within alveolar spaces

or

(2) Narrowing of alveolar spaces because of thickening of alveolar walls (often by inflammation)

4. Patterns of pneumonia

a. Diffuse

(1) Implies infectious agent entered lungs via bloodstream

(2) Typical pattern for viral pneumonias

(3) Inflammation is typically in the alveolar walls, which means it is an interstitial pneumonia

b. Locally extensive

(1) Cranioventral distribution implies infectious agent entered lungs via inhalation

(2) Typical pattern for bacterial pneumonias

(3) Inflammatory exudate is typically in bronchi, bronchioles, and alveoli, which means it is a bronchopneumonia

(4) Aspiration pneumonia is a bronchopneumonia. Exudate tends to be more necrotizing than suppurative

c. Focal

(1) Abscess or granuloma

(2) Blood-borne or inhaled agent

d. Multifocal: Most likely, blood-borne infection (i.e., embolic pneumonia)

B. Color

1. Red

a. Diffuse congestion (active or passive hyperemia)

b. Acute inflammation

2. Gray-red, plum-colored, dark red, or purple

a. Subacute to chronic inflammation

b. Atelectasis

3. White or tan areas or foci

a. Inflammation (abscesses, granulomas)

b. Fibrosis

c. Necrosis

C. Common causes of pneumonia

1. Horses

a. Rhodococcus equi: Bronchopneumonia in foals

b. Streptococcus equi: Bronchopneumonia

c. Streptococcus zooepidemicus: Bronchopneumonia or pleuritis

d. Adenovirus (Arabian foals with combined immunodeficiency disease [CID]). Bronchopneumonia

e. Pneumocystis carinii (Arabian foals with CID). Interstitial pneumonia

2. Cattle

a. Mannheimia haemolytica: Acute bronchopneumonia and pleuritis

b. Pasteurella multocida: Secondary opportunist; bronchopneumonia

c. Mycoplasma bovis: Subacute to chronic bronchopneumonia

d. Histophilus somni: Bronchopneumonia with or without pleuritis

e. Arcanobacterium pyogenes: Secondary opportunist; abscesses

f. Bovine respiratory syncytial virus

g. Infection with IBR virus, parainfluenzavirus, or bovine viral diarrhea (BVD) virus may predispose to secondary bacterial pneumonia

3. Sheep and goats

a. Mannheimia haemolytica

b. Lentivirus (lymphoid interstitial pneumonia of sheep; caprine arthritis-encephalitis virus of goats)

c. Lungworms ( Dictyocaulus filaria, Muellerius capillaris, Protostrongylus rufescens)

4. Swine

a. Pasteurella multocida: Bronchopneumonia

b. Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae

(1) Acute fibrinohemorrhagic bronchopneumonia and pleuritis

(2) Preferentially affects dorsocaudal areas of the lungs

c. Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae: Subacute to chronic bronchopneumonia

d. Streptococcus suis type II: Bronchopneumonia or pleuritis

e. Myoplasma hyorhinis: Pleuritis as part of polyserositis syndrome

f. Hemophilus parasuis: Bronchopneumonia or pleuritis or polyserositis (Glasser disease)

g. Porcine respiratory and reproductive syndrome (PRRS) virus

h. Porcine circovirus (postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome)

i. Swine influenzavirus

5. Dogs

a. Canine distemper virus

b. Canine adenovirus type 2

c. Canine herpesvirus (neonates)

d. Bacterial pneumonias generally secondary to immunocompromise. Bordetella bronchiseptica, Pasteurella multocida, E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae

e. Fungal pneumonias

(1) Blastomyces dermatitidis, Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides immitis, Cryptococcus neoformans

(2) Aspergillus fumigatus (immunocompromised animals)

f. Toxoplasma gondii

6. Cats

a. Feline rhinotracheitis virus and calicivirus may cause pneumonia but not a significant problem unless there is secondary bacterial infection

b. Cryptococcus neoformans

VII. Neoplasms of the respiratory tract

A. Primary neoplasms are uncommon

1. Bronchogenic (bronchial origin), bronchiolar, alveolar, and bronchial gland carcinoma

2. Nasal adenocarcinoma

B. Lungs are a common site of metastasis of carcinomas and sarcomas

VIII. Pleural effusions

A. Hydrothorax

1. “Edema” of the thoracic cavity

B. Hemothorax: Usually traumatic in origin

C. Chylothorax: Most commonly due to ruptured lymphatic duct (e.g., thoracic duct)

D. Pyothorax: Common causes:

1. Ruptured lung abscess

2. Extension of pneumonia or pleuritis caused by pyogenic bacterium

3. Puncture wound of thoracic wall

4. Traumatic reticulopericarditis sequelae in cattle

EXAMINATION OF THE CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM

I. Pericardium

A. A small amount of serosanguineous fluid in pericardial sac may be normal or a postmortem artifact

B. Hydropericardium

1. Excessive volume of clear to slightly yellow, watery to serous fluid

2. In diseases associated with generalized edema (e.g., congestive heart failure, hypoproteinemia)

3. Often accompanies ascites, hydrothorax

C. Pericardial sac containing clotted or unclotted blood: Hemopericardium. Rapid accumulation of blood leading to signs of acute heart failure: Cardiac tamponade

D. Fibrinous or fibrinosuppurative exudate

1. Bacterial pericarditis

2. Component of acute polyserositis

3. Associated with traumatic reticulopericarditis in cattle (i.e., hardware disease)

4. Inflammatory exudate may accompany adhesions to epicardium, visceral pleura, parietal pleura

E. Urate deposits on pericardial sac

1. Visceral gout in birds, reptiles

2. White, chalky deposits

II. External evaluation of the heart

A. Heart should taper toward apex and appear rounded at base

B. “Double apex” implies dilated right or left ventricular chamber

C. Excessively rounded at base implies dilated right or left atrial chamber

D. Petechiae or ecchymoses on epicardium

1. May indicate septicemia or endotoxemia

2. May be related to “agonal death,” especially in large animals

3. Similar hemorrhages may be seen on endocardium

E. Hemangiosarcoma of dogs. Commonly found in right atrium or auricle

III. Myocardium

A. Ratio of the thickness of the free wall of the left ventricle to the thickness of the free wall of the right ventricle is normally 2:1 to 3:1

B. Tan streaks in myocardium suggest myodegeneration, myonecrosis, myocarditis, or fatty infiltration. Areas of pallor may be due to postmortem autolysis, too

C. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) of cats. Thickening of left ventricular free wall and interventricular septum primarily

D. Dilative cardiomyopathy of cats, congestive heart failure of any species

1. Rounded heart externally

2. Often biventricular dilation

E. Postmortem blood clotting

1. “Currant jelly” clots: Dark red, gelatinous

2. “Chicken fat” clots: Separation of serum from cellular components

F. Ossa cordis: Two normal, triangular-shaped bones palpable in the interventricular septum near the base of the heart in cattle

IV. Endocardium

A. Endocardium covering myocardium is thin and transparent in small animals but may be white diffusely or in patchy areas because of greater thickness in large animals

B. Atrioventricular valves (right: Tricuspid, left: Mitral). Normally smooth, thin, semitransparent (small animals) to white

C. Pulmonic and aortic valves

1. Normally smooth, thin, white

2. Small (1-2 mm) firm, palpable nodules in free edges of the cusps of the aortic valve in large animals

V. Great vessels

A. Great vessels entering or exiting the heart are commonly examined (i.e., jugular veins, venae cavae, pulmonary artery, pulmonary veins, aorta)

B. Thrombi

1. Antemortem thrombi are attached to vascular endothelium. “Laminated” appearance, with layers of fibrin and blood, may be appreciated

2. Postmortem blood clots are not attached and are easily removed from the blood vessel. Usually homogeneous, gelatinous

C. Atherosclerosis

1. Primary vascular disease is uncommon in animals

2. Atherosclerosis may be seen as a sequela to hypothyroidism or diabetes mellitus

3. Thick-walled, pale yellow, tortuous arteries

VI. Some common cardiac congenital anomalies

A. Dogs

1. Patent ductus arteriosus: Several breeds (mostly small dogs)

2. Pulmonic stenosis: Inherited in beagle, English bulldog, Chihuahua

3. Subaortic stenosis: Inherited in Newfoundland, boxer, German shepherd

4. Persistent right aortic arch: Predisposition in German shepherd, Irish setter, Great Dane

B. Cats: Endocardial fibroelastosis. Burmese cats

C. Cattle

1. Ventricular septal defect: Usually toward the heart base

2. Valvular hematomas (hematocysts)

a. Atrioventricular valves of young animals

b. Seem to regress spontaneously

c. Not associated with functional abnormalities

VII. Inflammatory diseases of the heart

A. Bacterial endocarditis

1. Usually valvular

2. Dull, friable, yellow to gray masses of fibrin, exudate, necrotic debris

3. Fibrous base to these “vegetative” growths implies chronicity

4. Affected animal often has pre-existing extracardiac infection (e.g., dental or oral, liver abscess)

5. Isolates include Arcanobacterium pyogenes in cattle, Streptococcus spp., and Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae in swine, Streptococcus spp., and E. coli in dogs and cats

B. Myocarditis

1. Hematogenous spread of infection

2. Usually multifocal white to tan foci or streaks in myocardium

3. Some bacterial causes

a. Clostridium chauvoei in cattle (blackleg): Dark red foci of hemorrhage and necrosis

b. Clostridium piliformis (Tyzzer disease) in foals and laboratory animal species

4. Some viral causes

a. Canine parvovirus

b. Porcine encephalomyocarditis virus

c. Foot-and-mouth disease virus

5. Some protozoal causes

a. Toxoplasma gondii

b. Sarcocystis spp.

c. Often an incidental finding, without accompanying inflammation, in cattle

VIII. Conditions associated with degeneration or necrosis

A. Valvular endocardiosis of aged dogs

1. Multinodular thickening of atrioventricular valves

2. “Verrucous” or wartlike nodules, associated with mitral regurgitation murmurs

B. Nutritional myopathy: Most commonly associated with vitamin E or selenium deficiency

C. Toxic cardiomyopathy (e.g., ionophores, vitamin D, certain mycotoxins)

IX. Cardiovascular neoplasia

A. Hemangiosarcoma in dogs

1. Right atrium or auricle

2. Also commonly found in spleen, liver

3. Dark red, rather soft, with blood-filled channels

B. Lymphosarcoma in cattle

1. Right side of the heart most frequently

2. Firm, tan, homogeneous masses

3. Other common sites include abomasum and uterus

EXAMINATION OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL (GI) TRACT

I. Oral cavity

A. Developmental anomalies

1. Palatoschisis (cleft palate)

2. Cheiloschisis (cleft lip)

B. Erosions, ulcers, vesicles, papules on tongue, gingiva, buccal mucosa, or lips

1. May indicate viral infection (e.g., foot-and-mouth disease of ruminants, vesicular stomatitis of calves, vesicular exanthema of swine, bovine papular stomatitis), contagious ecthyma (“orf” or “sore mouth”) of sheep and goats, bovine viral diarrhea (BVD) virus, feline calicivirus

2. May start as clear fluid-filled vesicles or blisters

3. For some diseases, there may be similar lesions on coronary bands of hooves, udder, or mucocutaneous junctions

4. Bacterial causes

a. Fusobacterium necrophorum

(1) “Calf diphtheria”

(2) Necrotizing or pseudomembranous stomatitis

b. May occur secondary to viral infection

5. Other causes

a. Chemical injury

b. Associated with systemic disease (e.g., uremia)

c. Autoimmune disease

d. Trauma

C. Hyperplastic lesions

1. Gingival hyperplasia

2. Epulis

a. Indistinguishable grossly from gingival hyperplasia

b. Several histopathologic variants, one of which can be invasive or destructive (acanthomatous epulis)

D. Neoplasia

1. Squamous cell carcinoma

a. Tongue is most common site in cats

b. Tonsil is most common site in dogs

2. Oral melanoma: Usually malignant in dogs. Cutaneous melanomas tend to be benign

3. Canine oral papillomatosis

a. Caused by papovavirus

b. Usually in young animals

4. Fibrosarcoma: Cats and dogs

E. “Wooden tongue” in cattle

1. Actinobacillus lignieresii

2. Thickening of tongue owing to granulomatous inflammation and fibrosis

F. “Thrush”

1. Candida albicans (yeast) infection of tongue and esophagus

2. Secondary to an underlying debility, especially in young

II. Esophagus

A. Megaesophagus

1. Congenital

a. Associated with persistent right fourth aortic arch (Figure 7-2)

|

| Figure 7-2 Megaesophagus from a persistent right aortic arch, esophagus, dog. Dilation of the esophagus cranial to the heart is the result of failure of the right fourth aortic arch to regress during embryonic life (vascular ring abnormality). (Courtesy Dr. C.S. Patton, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tennessee.) |

b. Esophageal obstruction at base of heart and dilation cranial to this site

2. Acquired

a. Dilation of entire esophagus

b. Atrophy or degeneration of the muscularis

c. Idiopathic, or secondary to the following:

B. Esophageal parasites

1. Gongylonema spp.

a. Ruminants, pigs, horses

b. Thin, red, serpentine nematodes beneath mucosal surface

2. Spirocerca lupi in dogs. Nematode associated with granulomas or neoplasms (fibrosarcoma, osteosarcoma)

C. Esophageal erosions or ulcers

1. Reflux of gastric acid → esophagitis

2. Injury associated with stomach tubes

3. Viral infection (e.g., BVD virus)

4. Ulcers tend to be linear

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree