CHAPTER 51. Ovine/Caprine Medicine and Management

Natalie J. Coffer

HUSBANDRY

I. Behavior

A. Sheep

1. Exhibit strong flocking behavior and follow one another. Separating a sheep from the flock can cause signs of agitation and stress

2. Natural flight response can be used to the handler’s advantage to move them into races, chutes, or small pens for examinations or procedures

3. They are easily excitable. Handlers should move and restrain animals in such a way as to avoid excessive stress

4. Sheep observed to separate themselves from the rest of the flock or fail to keep up with the flock when being moved should be inspected for signs of illness

5. Fighting or challenging behavior includes snorting, stamping the foot, and head-butting

B. Goats

1. Exhibit herding behavior, and isolation from the herd can induce considerable stress. Goats have gregarious and inquisitive natures and, when handled frequently, can become companion animals

2. Goats that lag behind the herd when moving or isolate themselves from the herd should be inspected for signs of disease

3. Goats like to climb and will scale rocks and trees and, if given the opportunity, cars and farm equipment

4. Fighting behavior includes rearing on hind legs and head-butting

II. Management

A. Sheep

1. Raised for meat, wool, and milk. Flock management systems can vary depending on many factors, including desired end-product, lambing frequency, lambing season, and regional climate

2. Sheep kept on pastures need access to shelter in inclement weather. Periparturient ewes should be housed in smaller pens to allow close monitoring for parturition problems. If possible, lambing stalls should be provided to facilitate bonding with lambs

3. Regular pasture rotation should be part of any management system to reduce the build-up of internal parasite larvae on pastures

B. Goats

1. Raised for meat, fiber (hair), and milk

2. Need access to grazing and browsing areas. Goats kept at pasture need access to shelter in inclement weather. As with sheep, close monitoring near parturition and kidding pens are recommended for goats

3. Anthelmintic resistance is a significant problem in goat herd management worldwide. Strategic anthelmintic use, alternative parasite control methods, and regular pasture rotation are essential to control internal parasite infestations and prevent further development of anthelmintic resistance

III. Nutrition

A. Sheep: Grass and roughage grazers

B. Goats: Browsers and grazers. Prefer varied diet. Often used for brush management

C. Rumen microbe fermentation of forage and other feedstuffs provides energy for the ruminant in the form of volatile fatty acids (VFAs), mainly acetic, propionic, and butyric acids. Roughly 50% of available energy in the ruminant diet is provided in form of VFAs. Digestion of microbial tissue provides proteins and essential amino acids

D. Most flocks of sheep and goats in United States are maintained on pasture- or range-based systems. In general, roughly 80% of diet of sheep and goats is from forage

E. Good nutrition for sheep and goats can be maintained with many perennial grasses. Legumes, annual grasses, and prudent grain supplementation can be added. Oversupplementation with alfalfa, grain, or both can lead to rumen acidosis, bloat, and urolithiasis

F. A minimum of 7% crude protein is required for normal rumen flora growth and function. Dietary protein content should vary depending on stage of growth, weight-gain goals, and lactation or pregnancy status

G. Digestible energy and nutrient requirements can vary depending on stage of growth, reproductive status, and production goals

H. Mineral deficiencies and toxicities can occur when macrominerals or microminerals in the diet are improperly balanced

1. High phosphorus content can lead to urinary calculi formation. To prevent urolithiasis, a calcium-to-phosphorus ratio of 2:1 or more should be maintained

3. Sheep are more susceptible to copper toxicity than are other ruminants and horses because of their increased efficiency in retaining copper. Goats are more resistant to copper toxicity than sheep

a. Dietary copper levels should not exceed 10 parts per million (ppm)

b. Copper deficiencies in pregnant ewes can lead to enzootic ataxia in lambs. Minimum of 5 ppm dietary copper is recommended

c. Secondary copper deficiency can occur with high levels of molybdenum

4. Hypocalcemia or milk fever can occur in prepartum or postpartum sheep or goats with multiple neonates

RESTRAINT AND HANDLING

I. Physical examination of small ruminants should begin with observation from a distance, preferably in the animal’s normal environment whenever possible

A. Observe interaction with herd mates, behavior, response to environmental stimuli, respiratory pattern, fleece or hair condition, posture, and gait

B. Further examination requires proper restraint

II. Restraint

A. Sheep

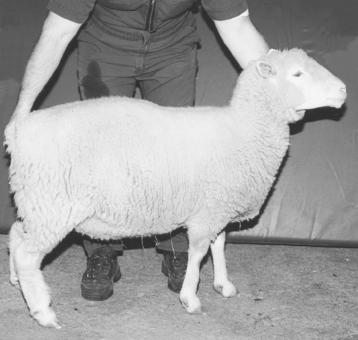

1. After moving into race or small pen, sheep can be grabbed by the mandible and tail or caught by crook or lariat (Figure 51-1)

|

| Figure 51-1 The handler is on the left side of the sheep with his left hand under the jaw and his right hand holding the tail. It would be acceptable for him to be kneeling with one knee (usually the right) on the ground and the right hand holding the right rump. (From Pugh DG. Sheep & Goat Medicine. Philadelphia, 2002, Saunders.)⋆⋆⋆ |

2. Wool should not be grabbed to restrain sheep. May result in damage to fleece

3. Handler should stand to the side of the sheep and put one hand under the mandible and one on the tail or under the flank. Sheep may be positioned on rump for examination, foot trimming, or shearing

B. Goats

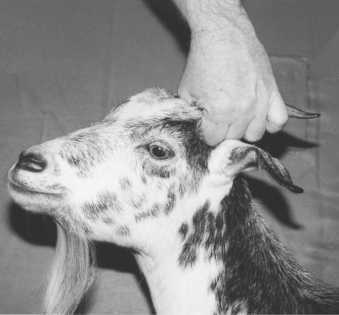

1. Can be restrained by catching and holding the goat’s neck, beard, mandible and tail, or base of horns. Grabbing the tip of horns may cause fracture of horn or skull

2. May be restrained by holding the head and straddling the withers or neck or by holding the goat against a wall or fence (Figure 51-2)

|

| Figure 51-2 Goats can be restrained by their horns if the handler grasps near the skin and keeps the rear of the animal under control. If the handler does not control the animal’s rear and the goat flips around, it may injure its neck. Grasping the horn near the tip may result in breaking the horn and possibly fracturing the skull. (From Pugh DG. Sheep & Goat Medicine. Philadelphia, 2002, Saunders.) |

III. Body condition score (BCS)

A. Sheep

1. Heavy fleece may conceal the BCS. Must palpate fat and muscle around the dorsal and transverse spinous processes of lumbar vertebrae

2. Scoring system ranges from 1 (emaciated) to 5 (obese)

3. Monitoring BCS is one aspect of monitoring flock health

a. Especially important to monitor BCS during breeding and parturition to ensure that ewes are not overconditioned or underconditioned

b. Inappropriate BCS can lead to a variety of reproductive insufficiencies and periparturient diseases

B. Goats

1. Scoring system ranges from 1 to 5

2. Similar to sheep

MEDICAL DISORDERS

I. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) disorders

A. Complete physical examination should include oral examination

B. Normal dental formula for adult sheep and goats: 2 (incisors 0/3, canines 0/1, premolars 3/3, molars 3/3) = 32 teeth

C. Oral cavity should be inspected for broken, loose, or missing teeth; uneven wear; foul odor; swellings on mandible or maxilla; labial, lingual, or buccal abnormalities or injuries; foreign bodies; and lingual and pharyngeal function

D. Actinomycosis

1. “Lumpy jaw”

2. Caused by Actinomyces bovis, gram-positive rods

3. Chronic, suppurative granulomatous infection of bony and soft tissue structures of oral cavity

4. Successful treatment includes early antimicrobial therapy and surgical debridement

E. Actinobacillosis

1. Actinobacillus lignieresii

2. Pleomorphic, facultative anaerobic gram-negative rod bacteria

3. Infections result in granulomatous abscesses in soft tissues of oral cavity, larynx, and associated lymph nodes

4. Involvement of the tongue known as “wooden tongue”

5. Inoculation of mucosal tissue may result after injury from coarse feeds

6. May spread hematogenously or via lymphatics to other sites

7. Successful treatment requires early aggressive antimicrobial therapy and surgical debridement

F. Tooth-root abscesses

1. Presents as swelling on mandible or maxilla. Draining tracts often present. Affected tooth may be loose on palpation; gingival swelling may be noted

2. Radiographs may confirm diagnosis with the presence of bony lysis around the tooth root

3. Extraction of affected tooth, debridement of affected bone, and antimicrobial therapy are often indicated

G. Contagious ecthyma

1. Parapox virus; zoonotic

2. Orf: Sore mouth

3. Clinical signs include vesicles on mucocutaneous junction of lips and nose. Erupted vesicles result in ulcerated mucosa and scabs. Lesions also occur on udder, coronary bands, and eyelid margins

4. Young animals are more severely affected; painful oral lesions often interfere with nursing

5. Vaccination with live virus may reduce the frequency of outbreaks in affected herds. Use of vaccine is often regulated by state officials

6. Virus may remain viable in the environment for extended periods. Elimination from affected herds is challenging

H. Bluetongue virus

1. RNA orbivirus is transmitted by Culicoides

2. Ulcerative lesions appear on oral mucosa, muzzle, and lips as well as erythema and edema. Coronitis and diffuse dermatitis can also occur. Exposure of ovine fetuses to the blue tongue virus can result in hydrancephaly and other developmental abnormalities

3. Hyperemia and swelling of the muzzle, lips, and ears and cyanosis of the tongue may occur

I. Foot-and-mouth disease

1. Reportable disease

2. Caused by highly contagious ribonucleic acid (RNA) picornavirus, genus Apthovirus

3. Spread by aerosol and mechanical vectors

4. High morbidity, low mortality disease

5. Lesions form on skin and mucous membranes 2 to 14 days post exposure. Vesicles appear, and rupture results in erosions in the skin. Secondary bacterial infection may follow

6. Characteristic lesions occur on lingual, nasal, and buccal tissue; interdigital skin; coronary bands; and teats

7. Infection may be undetectable in sheep and goats and therefore may be virus carriers and amplifiers

J. Reportable disease caused by rhabdovirus

K. Sheep and goat pox

1. Reportable disease

2. Caused by two related poxviruses

3. Transmitted by aerosol, direct contact, and mechanical vectors

4. Can persist for long periods in environment

5. Erythema and papular pox lesions occur on oral, nasal, and ocular mucous membranes. Respiratory tract and peritoneal cavity may also be affected

6. Fever and upper respiratory signs can occur initially

L. Megaesophagus: Reported in Alpine and Nubian goats and Southdown sheep. May be associated with Sarcocystis spp.

II. GI diseases

A. Diagnostic tests

1. Rumen fluid analysis

2. Abdominocentesis

3. Fecal examination

4. Radiography-ultrasonography

5. Exploratory laparotomy

B. Bloat

1. Free gas bloat

a. Accumulation of fermentation gases in rumen

(1) Due to excessive production with high-grain diets

(2) Due to failure of eructation with esophageal dysfunction or obstruction

b. Clinical signs include abdominal distension and filling of left paralumbar fossa

c. Respiratory distress and death by respiratory failure may occur if left untreated

2. Frothy bloat

a. Rumen fermentation gases trapped in stable foam

b. Can occur with consumption of legumes, lush cereal grain grasses, and high-concentrate rations

c. Passing of orogastric tube often does not decompress rumen. Intrarumenal administration of poloxalene or mineral oil may help disrupt foam and release gas

d. Prevention measures include slow introduction to legumes and high-grain diets and supplementing with poloxalene, monensin, or lasalocid

C. Rumen acidosis

1. Resulting from overconsumption of rapidly fermentable carbohydrate feeds

2. Rumen pH drops, allowing lactic acid–producing bacteria to proliferate. A further drop in rumen pH results in death of rumen protozoa and lactic acid users

3. Systemic lactic acidosis and dehydration are sequelae

4. Rumen lavage via nasogastric tube or rumenotomy is often indicated

5. Acidic pH of rumen fluid can damage rumen mucosal lining, resulting in rumenitis. Translocation of bacteria and toxins into portal and systemic circulation may occur. Loss of rumen flora production of thiamine can lead to polioencephalomalacia (PEM)

D. Abomasitis and abomasal ulcers

1. Causes include rumen acidosis, infectious causes, finely ground or pelleted feeds

2. Clinical signs include melena, reduced appetite, and bruxism

E. Abomasal emptying defect in sheep

1. Described in Suffolk sheep

2. Characterized by weight loss, loss of appetite, and abdominal distension

3. Clinical pathology changes typical of abomasal obstructive disease: Elevated rumen chloride, serum hypochloremia, metabolic alkalosis, and hypokalemia

4. Undetermined cause. Medical and surgical treatment often unsuccessful

F. Neonatal diarrhea in kids and lambs

1. Multifactorial disease complex influenced by environmental factors, infectious agents, nutrition, and immune status of the neonate

2. Important infectious causes of neonatal diarrhea include enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), Cryptosporidium spp., rotavirus, Salmonella spp., and Giardia organisms

a. ETEC

(1) Occurs in lambs and kids less than 10 days old, commonly in neonates 1 to 4 days of age

(2) Pathogenesis mediated by two virulence factors, fimbria K99 and F41, and enterotoxin. Enterotoxin-mediated diarrhea causes hypersecretion of fluids and electrolytes, resulting in dehydration, acid-base imbalance, and electrolyte deficiencies in the affected animal. Septicemia can also occur

(3) Fecal culture and serotyping of fimbriae support diagnosis

(4) Treatment involves supportive care, including oral or fluid therapy, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and systemic antimicrobials if septicemia is suspected

(5) Preventative measures include good hygiene in lambing and kidding areas and periparturient vaccination of ewes and does with a bovine ETEC vaccine

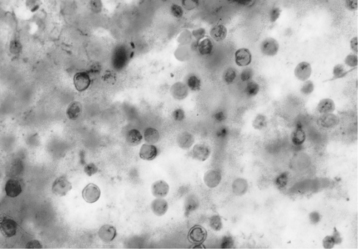

b. Cryptosporidium parvum spp.

(1) Causes diarrhea in lambs and kids 5 to 10 days of age

(2) Zoonotic disease

(3) Protozoal parasite that infects villus tips of intestinal enterocytes, resulting in malabsorptive diarrhea

(4) Oocytes are immediately infective. Sporulation can occur within intestine, resulting in autoinfection. Disease course can therefore be prolonged

(5) Diagnosis is confirmed via acid-fast staining of fecal smears. Fecal floats are less reliable (Figure 51-3)

|

| Figure 51-3 Red-staining Cryptosporidium on a blue-green background in a fecal smear prepared with an acid-fast stain. This protozoal parasite induces villous atrophy and decreased digestion. (From Pugh DG. Sheep & Goat Medicine. Philadelphia, 2002, Saunders.) |

(6) Treatment consists of supportive care. Infection can be self-limiting

(7) Isolation of affected animals and good hygiene can prevent spread of disease

c. Rotavirus

(1) Group B virus affects lambs and kids

(2) Animals 2 to 14 days old are most commonly affected. Older animals can be affected

(4) Diagnosis supported by finding rotavirus particles by electron microscopy of fecal samples

(5) Treatment is supportive care

d. Salmonella spp.

(1) Causes diarrhea in lambs and kids of any age. High mortality and morbidity in neonates younger than 1 week

(2) Zoonotic disease

(3) Causes acute and chronic enteritis and colitis, pneumonia, septicemia, and other syndromes

(4) Causes invasive enteritis and severe inflammation and necrosis of small and large intestine. Diarrhea caused by Salmonellosis is often characterized by blood and mucosal shreds

(5) Diagnosis is confirmed by fecal culture, polymerase chain reaction techniques or identification of organism on histopathologic examination of intestine

(6) Treatment consists of supportive therapy. Antimicrobial administration is indicated in cases of septicemia

e. Giardia spp.

(1) A flagellated protozoan parasite that causes diarrhea in 2- to 4-week-old lambs and kids

(2) Diarrhea is often transient, and infection can be self-limiting

(3) Affected animals may shed cysts for long periods

G. Diarrhea in older lambs and kids

1. Biotypes A-D clostridial enterotoxemia

a. Caused by colonization of GI tract and rapid proliferation of Clostridium perfringens, an anaerobic, spore-forming rod

b. Type A enterotoxemia

(1) Soil inhabitant and normal GI commensal in some animals

(2) Can produce high levels of α-toxin, a phospholipase that can cause hemolysis, increased vascular permeability, and villous necrosis in GI tract

(3) Clinical signs include icterus (“yellow lamb disease”), fever, lethargy, anemia, hemoglobinuria, and rapid death

c. Type B enterotoxemia

(1) Produces α-toxins, β-toxins, and ε-toxins. Causes hemorrhagic necrotic enteritis (“lamb dysentery”)

(2) Rarely seen in North America

(3) High morbidity and mortality, near 100%

d. Type C enterotoxemia

(1) Sudden dietary changes or disruption of normal GI flora can allow overgrowth of normal GI commensal C. perfringens and production of α-and β-toxin

(2) Pathogenesis mediated primarily by β-toxin

(3) Clinical signs include depression, diarrhea, nervous signs, and sudden death

(4) Hemorrhagic necrosis of jejunum and ileum seen at postmortem. Nervous signs may include tetany and opisthotonos in lambs

(5) High mortality, nearly 100%

(6) Known as “struck” in adult sheep

(7) Multivalent vaccines available for prevention of diseases in ruminants

e. Type D enterotoxemia

(1) Associated with high-energy diets or sudden changes in diet resulting in normal GI commensal C. perfringens overgrowth and production of ε-toxin (“overeating disease”)

(2) Can occur in sheep of any age. Most commonly seen in lambs 3 to 8 weeks old. Commonly lambs of heavily lactating ewes

(3) Clinical signs include depression, nervous signs, hyperglycemia, glucosuria, sudden death. Postmortem signs include small areas of hemorrhage on GI mucosa, edema of various organs, especially kidneys (“pulpy kidney disease”), resulting from the ability of epsilon toxin to increase mucosal permeability

(4) Nervous signs include opisthotonos, ataxia, muscle tremors, seizures

(5) High mortality rate. Death can occur within hours

(6) Multivalent vaccines are available for prevention of diseases in ruminants

2. Coccidiosis

a. One of the most economically important diseases in livestock

b. Common cause of diarrhea in weanling lambs and kids. Also occurs in young lambs and kids younger than 3 to 4 weeks of age. Occurs less commonly in adults. Subclinical infections can be a cause of poor weight gain and production losses

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree