CHAPTER 4. Dentistry

Sandra Manfra Marretta and Rebecca S. McConnico

Dental Anatomic Review

I. Dental formulas

| Deciduous Dentition | Permanent Dentition | |

|---|---|---|

| Dog | 2 (I3/3, C1/1, P3/P3) = 28 teeth | 2 (I3/3, C1/1, P4/P4, M2/M3) = 42 teeth |

| Cat | 2 (I3/3, C1/1, P3/P2) = 26 teeth | 2 (I3/I3, C1/C1, P3/P2, M1/M1) = 30 teeth |

A. Incisor teeth: There are three incisor teeth in each quadrant in dogs and cats, the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd incisors. These teeth are used for cutting and grooming

B. Canine teeth: There are a total of four canine teeth in the dog and cat. These teeth are used for puncturing and tearing

C. Cheek teeth: The cheek teeth are located behind the canine teeth and are divided into premolars and molars. Premolars are used for shearing, molars for crushing

1. Premolars: Adult dogs have four maxillary premolars and four mandibular premolars on each side. The 1st maxillary premolars are not present in the cat, and the 1st and 2nd mandibular premolars are not present in the cat. The maxillary premolars are the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th premolars in the cat. The mandibular premolars in the cat are the 3rd and 4th premolars

2. Molars: There are two maxillary molars on each side in the dog, the 1st and 2nd maxillary molars. In the cat there is only one very small maxillary molar on each side, the 1st maxillary molar. There are three mandibular molars on each side in the dog, the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd molars. In the cat there is one mandibular molar on each side, the 1st molar.

3. Carnassial teeth: The largest maxillary cheek teeth in the dog and cat are the maxillary 4th premolars. The largest mandibular cheek teeth in the dog and cat are the mandibular 1st molars. An easy way to remember the proper identification of the cheek teeth in the dog and cat is to remember that the largest cheek tooth in the maxilla is the 4th premolar and the largest cheek tooth in the mandible is the 1st molar and count rostrally or mesially.

II. Adult root structure

A. Dogs: All incisor and canine teeth have one root. The first maxillary cheek tooth (1st premolar) has one root, the next two (2nd and 3rd premolars) have two roots, and the next three (4th premolar, 1st molar, and 2nd molar) have three roots. The mandibular cheek teeth in the dog all have two roots except the first and last cheek teeth, which have one root

B. Cats: All incisor and canine teeth have one root. The first maxillary cheek tooth (2nd premolar) has one root, the next tooth (3rd premolar) has two roots, and the next tooth (4th premolar) has three roots. The small maxillary 1st molar in the cat has two small roots. The mandibular cheek teeth (3rd and 4th premolars and 1st molar) in cats all have two roots

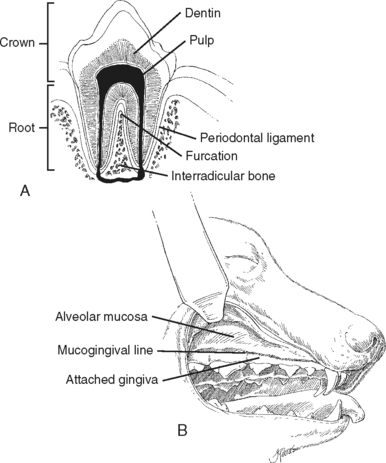

III. Gross anatomy of the tooth and surrounding bone (Figure 4-1)

|

| Figure 4-1 A, Anatomy of the tooth. B, Gingival anatomy. (From Birchard SJ, Sherding RG. Saunders Manual of Small Animal Clinical Practice, 3rd ed. St Louis, 2006, Saunders.) |

A. Crown: Portion of tooth that is normally visible in the mouth

B. Root: Portion of tooth that is imbedded in the bone of the maxilla or mandible

C. Enamel: Hardest substance in the body that covers the outer layer of the crown

D. Dentin: Intermediate layer of the tooth and forms the bulk of the calcified tooth structure

E. Pulp: Innermost layer of the tooth and consists of nervous, vascular, and loose connective tissue

F. Cementum: Covers the outer layer of the root of the tooth

G. Cemento-enamel junction: Separates the crown from the root and separates the portion of the tooth covered by either enamel or cementum

H. Furcation: The point at which the roots of a multirooted tooth branch from the crown

I. Apex: Tip of the root of a tooth through which blood vessels and nerves enter the tooth

K. Periodontal ligament: Collagenous fibrous bundles that attach the cementum of the root of the tooth to the alveolar bone (radiographically the periodontal ligament appears as a radiolucent [black] line around the roots of teeth)

IV. Tooth type. Brachyodont: Short crown-root ratio with a true root; once apex forms, tooth growth stops

Common Dental Diseases in Dogs and Cats

I. Periodontal disease

A. Pathophysiology: Most common disease diagnosed in dogs and very common disease in cats. Periodontal disease increases significantly with increasing age and is more severe in small-breed dogs. Periodontal disease is caused by an accumulation of bacteria in the form of plaque on the surface of the teeth, which causes inflammation of the surrounding tissues. As periodontal disease progresses, the periodontal ligament that attaches the root of the tooth to the alveolar bone is destroyed and attachment of the tooth to the bone is lost, the gingiva recedes, the furcation of multirooted teeth are exposed, and ultimately the attachment of the tooth is severely compromised, which results in tooth loss

B. Stages of periodontal disease and diagnostic evaluation

1. Stage I (gingivitis): Gingiva is inflamed but there is no attachment loss

2. Stage II (early periodontal disease): Periodontal probing and dental radiographs may indicate attachment loss of up to 25%, with the teeth remaining stable

3. Stage III (moderate periodontal disease): Periodontal probing and dental radiographs may indicate attachment loss between 25% and 50% of the root length, and teeth may begin to become mobile

4. Stage IV (severe periodontal disease): Periodontal probing and dental radiographs may indicate attachment loss greater than 50%, and there is severe loss of supporting tooth structures and teeth become loose

C. Clinical presentations of periodontal disease

1. Common clinical presentations of periodontal disease: Mobile teeth, periodontal and periapical abscesses with secondary facial swelling, gingival recession, mild to moderate gingival hemorrhage, and deep periodontal pockets with secondary oronasal fistula formation with secondary chronic rhinitis

2. Uncommon clinical presentations of periodontal disease: Severe gingival sulcus hemorrhage, pathologic mandibular fractures, painful contact mucosal ulcers, intranasal tooth migration, osteomyelitis, and ophthalmic problems

D. Treatment

1. Dental charting with the patient anesthetized using a periodontal probe and dental radiographs to assess attachment loss

2. Supragingival and subgingival scaling

3. Root planning and subgingival curettage

4. Polishing or irrigation

5. Gingivectomy

6. Open-flap curettage with augmentation of bony defects

7. Perioceutics

8. Exodontia (extractions)

9. Oronasal fistula repair

10. Home care

II. Endodontic disease

A. Pathophysiology: Endodontic disease refers to disease of the pulp of the tooth or the inner aspect of the tooth that contains the blood vessels and nerves of the tooth. The most common cause of endodontic disease in small animals is dental trauma. A series of events may occur in some fractured teeth with exposed pulp, which can result in significant clinical problems. This series of events includes pulpal exposure, bacterial pulpitis, pulp necrosis, periapical granuloma, periapical abscess, acute alveolar periodontitis, osteomyelitis, and sepsis

B. Teeth most commonly fractured

1. Dogs: Canine teeth, incisors, and maxillary fourth premolars

2. Cats: Canine teeth

3. Any tooth in a dog or cat may be fractured, although less frequently

C. Stages, clinical signs, and evaluation of endodontic disease

1. Acute pulpal exposure (acute endodontic disease): Animals may hypersalivate, they may be reluctant to eat, and the tooth will bleed at the site of the pulpal exposure. A dental explorer under anesthesia can be inserted into the pulp canal and the pulp will bleed

2. Chronic pulpal exposure: Facial swelling, sneezing, nasal discharge, or mucosal or cutaneous fistulas. A dental explorer under anesthesia can be inserted into the pulp canal, but the pulp is necrotic and will not bleed

D. Radiographic changes associated with chronic endodontic disease

1. Periapical lysis (radiolucency around apex or dark halo around root tip)

2. Apical lysis (radiographic loss of the apex)

3. Large endodontic canals compared with contralateral tooth (when teeth are affected with endodontic disease when a dog is young, the pulp remains large and dentin is not deposited in the tooth)

4. Radiographic loss of tooth structure to pulp canal

E. Treatment

1. Vital pulpotomy: Limited to very recent pulpal exposure in young dogs with very large pulp canals and is an attempt to maintain the viability of the pulp until at least the tooth is mature and the pulp canal is more narrow and the dentin is thicker and stronger, at which time a conventional root canal procedure may be performed if necessary

2. Conventional endodontic therapy or nonsurgical root canal therapy: Most common form of endodontic therapy involving removal of the pulp tissue through the crown of the tooth and placement of an inert material in pulp canal to prevent infection associated with necrotic pulp

3. Surgical endodontic therapy: Rarely performed endodontic therapy and involves conventional endodontic therapy and amputation of the apex of the tooth with closure of the remaining apical portion of the root

III. Feline tooth resorptive lesions

A. Pathophysiology: The cause of feline tooth resorptive lesions is unknown; however, proposed theoretical contributing factors in feline tooth resorption include excess vitamin D and excessive occlusal stress caused by eating large, dry kibble. Feline tooth resorptive lesions are caused by odontoclasts and can develop anywhere on the root surface, not just close to the cementoenamel junction; resorption on the enamel as the initial event is rarely observed. Resorptive lesions that occur at the cementoenamel junction are filled with highly vascular and inflamed granulation tissue. These lesions are often painful and bleed when probed with a dental explorer. Tooth resorption in cats is frequently progressive, and the resorptive lesions continue to enlarge until the roots of affected teeth are completely resorbed or the crown of the tooth breaks off, leaving behind remnants of resorbing roots

B. Teeth affected by feline tooth resorptive lesions: All types of teeth may be affected, but the mandibular 3rd premolars are the most frequently affected teeth

C. Clinical signs and evaluation of feline tooth resorptive lesions

1. Resorptive lesions are often painful when the lesion involves the crown

2. Lesions may be hidden from view by plaque, dental calculus, or inflamed gingival tissue

3. Dental explorer used to localize lesions: when explorer encounters a resorptive lesion, it will fall into the irregular area of resorption

4. Dental radiographs necessary to determine the full extent of the resorptive process and to determine the appropriate treatment plan

D. Treatment options

1. Restoration: Lesions that extend into the dentine but do not involve pulp tissue were previously restored; however, restoration of these teeth has been shown to be unsuccessful, so no longer recommended

2. Conservative management: Resorptive lesions involving only the root and not the crown can be monitored both clinically and radiographically

3. Whole tooth extraction: Ideal but often not possible with advanced lesions

IV. Feline gingivostomatitis

A. Pathophysiology: The cause of feline gingivostomatitis, also referred to as lymphoplasmacytic stomatitis or lymphocytic plasmacytic gingivitis stomatitis, is unknown; however, there may be an immunologic basis for this condition and potential involvement of various viral agents

B. Oral pathologic findings: Severe inflammation may be focal or diffuse, including gingivitis, stomatitis, and inflammation of the palatoglossal folds

C. Diagnosis

1. Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) and FeLV tests: Often negative

2. Complete blood cell count (CBC) and serum chemistry: Hypergammaglobulinemia

3. Histopathology: Submucosal inflammatory infiltrate of plasma cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils

4. Dental radiographs: To rule out resorptive lesions and bone loss secondary to periodontitis or oral tumors

D. Treatment options

1. Initial treatment: Periodontal therapy and home care with corticosteroid and antibiotic therapy as needed

2. Medical management alone often inadequate

3. In refractory cases, extraction of the teeth is the treatment of choice (including all the premolars and molars, and in some cases all the teeth may require extraction)

4. Other treatment options: Laser thermoablation combined with cyclosporine therapy if extraction of teeth is not desired

V. Miscellaneous small animal dental or oral diseases

A. Normal occlusion and malocclusions

1. Normal scissors bite: The upper incisors are rostral to the lower incisors

2. Undershot (mandibular prognathic bite): The mandible is longer than the upper jaw, and the lower incisors are rostral to the upper incisors

3. Overshot (mandibular brachygnathic bite): The mandible is shorter than normal, and the upper incisors are significantly rostral to the lower incisors

B. Abnormal number of teeth

1. Persistent or overly retained deciduous teeth: Common in small-breed dogs, and retained deciduous teeth should be extracted as soon as possible to help prevent the permanent teeth from erupting in abnormal locations

2. Abnormal number of teeth

a. Supernumerary teeth: Common in dogs and may be the result of either a genetic defect or a disturbance during tooth development and require extraction if causing dental crowding

b. Oligodontia: A rare congenital absence of many but not all teeth

c. Hypodontia: Absence of only a few teeth is a relatively common genetic fault often involving missing premolar teeth

C. Dental wear

1. Attrition: Dental wear caused by tooth-to-tooth frictional contact

2. Abrasion: Dental wear caused by frictional contact of a tooth with a non-dental material

3. Teeth respond to dental wear by laying down tertiary or reparative dentin, which is visible as a dark solid brown spot that cannot be entered with a dental explorer

4. Very rapid dental wear may result in pulpal exposure that requires endodontic therapy or extraction

D. Enamel hypoplasia

1. Cause: A disruption of the ameloblasts during the first several months of life while the teeth are developing, which may be associated with periods of high fever, infections (especially canine distemper), nutritional deficiencies, disturbances in metabolism, systemic disorders, and trauma

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree