CHAPTER 4. Breeding Soundness Examination of the Mare

OBJECTIVES

While studying the information covered in this chapter, the reader should attempt to:

■ Acquire a working understanding of the procedures used for performing a breeding soundness examination of the mare.

■ Acquire a working understanding of how abnormalities of the genital tract may adversely affect fertility of the mare.

STUDY QUESTIONS

1. List information (history) that should be obtained to assess prior reproductive performance and to identify potential problems to be considered in a breeding soundness examination of a mare.

2. Describe procedures that are integral parts of the breeding soundness examination of the mare (e.g., assessment of vulvar conformation, vaginal speculum examination, procurement of specimens for uterine cytology, culture and biopsy).

3. List benefits of a properly taken and interpreted uterine cytology specimen.

4. List abnormalities that can be detected only with uterine biopsy.

5. List abnormalities that can be detected with intrauterine endoscopy.

6. Summarize the purposes for performing a breeding soundness examination of a mare.

HISTORY

A breeding soundness examination should begin with a gathering of all pertinent reproductive history regarding the mare. A thorough history may uncover information about a mare that may not otherwise be obtained. For instance, the following queries should be answered: How old is the mare? Has the mare been bred previously? If so, has she become pregnant and delivered any foals? How many foals? How long since she last foaled? Has she been bred each year? Has she been bred to fertile stallions with good breeding management procedures? Has she been bred to different stallions each year? Has she had any difficulties associated with foaling? Were any diagnoses of early pregnancy loss confirmed? Has she had any abortions or stillbirths? If so, at what gestational ages were pregnancies lost? Has the mare had any genital discharges? Has the mare previously been treated for genital infection? If so, what treatments were administered and when?

Mare age is important because, as a population, mares become less fertile with increasing age. A recent study involving Quarter Horse–type mares in good body condition revealed that for every year increase in age, the odds ratio for becoming pregnant on foal-heat breeding was 0.937 (i.e., approximately a 6% lower chance of becoming pregnant). In another study that investigated some of the factors affecting fertility in Thoroughbreds bred in central Kentucky, once mares passed the age of 10 years, odds ratios for becoming pregnant during the season significantly declined (Table 4-1).

| CL, Confidence limit; NS, not significantly different from reference age group; S, significantly different ( P <0.05) from reference age group (mares ≤5 years of age). | ||||

| Investigated with a stepwise multiple logistic regression model, adjusting for factors that significantly affected fertility during one season at a large Thoroughbred breeding farm in central Kentucky. Mares older than 10 years of age had significantly lower odds of becoming pregnant. | ||||

| Odds Ratio | Lower CL | Upper CL | P < 0.05 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mare age: 6-10 yr | 0.89 | 0.63 | 1.20 | NS |

| Mare age: 11-15 yr | 0.66 | 0.45 | 0.92 | S |

| Mare age: 16-20 yr | 0.46 | 0.29 | 0.73 | S |

| Mare age: >20 yr | 0.33 | 0.13 | 0.66 | S |

The status of the mare at the beginning of the year (i.e., foaling mare, mare that delivered a foal that year; maiden mare, mare that has not been bred in previous years; barren mare, mare bred the previous year that did not become pregnant; not bred mare, mare that the owner elected not to breed the previous year; or aborted mare, mare that became pregnant the previous year but lost the conceptus before a live foal could be born) can also be a significant predictor of expected fertility. A number of studies have identified maiden and foaling mares as the most fertile groups in broodmare bands; other groups of mares (particularly barren mares) are usually less likely to become pregnant and produce foals.

One should also collect information regarding the mare’s estrous cycle. Mares are seasonal breeders with the peak of fertility corresponding to the longest days of the year. The mares typically have normal estrous cycles during the physiologic breeding season (spring and summer), then enter a state of reproductive quiescence in the late fall, as day length decreases. Mares that are reproductively normal generally enter into estrus (heat) every 18 to 24 days (approximately every 3 weeks) during the breeding season, with heats that typically last for a period of 4 to 7 days (see Chapter 2). Because of seasonal variations in the duration of estrus, a better indicator that the mare has regular estrous cycles is that the period between heats is 14 to 16 days. This interval remains relatively constant regardless of season. Whether or not the mare has normal estrous cycles and exhibits strong outward signs of heat (i.e., is sexually receptive) when exposed to a stallion during estrus should be noted. In addition, the method of teasing should be obtained because most mares fail to show strong signs of estrus unless teased by a stallion. Numerous mare owners believe otherwise, yet we have teased mares with a stallion when the owners thought the mares were showing heat to a gelding or another mare, often finding the mares were not in estrus. In contrast, we have also teased mares thought by the owners to be out of heat when we suspected they actually were in heat (based on palpation findings) and usually found that the mares express behavioral estrus when presented to a stallion.

Shortened estrous cycles (e.g., less than 18 days) suggest the possibility of an underlying uterine infection (i.e., acute endometritis causing premature luteolysis). Lengthened estrous cycles in nonbred mares suggest the possibility of prolonged luteal function; in mares that have been bred, the possibility exists for early embryonic or fetal death. A less likely cause of irregular estrous cycles is endocrine dysfunction. If a mare has regular estrous cycles, the likelihood of endocrine dysfunction is low.

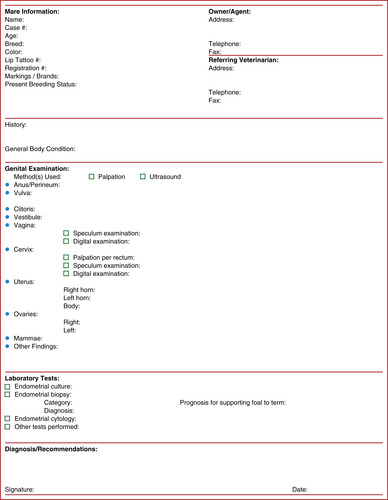

If possible, the examiner should collect previous breeding and medical records regarding the mare of interest and determine specifically whether the mare has had any reproductive or general medical problems that have necessitated treatment. A variety of ailments may reduce or abolish a mare’s reproductive potential. A sample breeding soundness examination form for recording of history, examination findings, diagnosis, and treatment recommendations is provided in Figure 4-1.

GENERAL PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Just because a mare is being examined for reproductive potential does not mean that her general body condition should be ignored. Texas workers, using a body condition scoring system of 1 to 9, found that mares with body condition scores of 5 or more had higher pregnancy rates and fewer cycles per pregnancy than mares with lower body condition scores. They also found that mares that entered the breeding season in high body condition, and were maintained in high body condition during the season, had earlier onset of regular estrous cycles and higher pregnancy rates and were less likely to lose pregnancies than were mares that entered the breeding season in poor body condition or that lost body condition during the breeding season.

Good general health also extends the longevity of broodmares and favors the ability of a mare to support a pregnancy to term and provide sufficient high-quality colostrum/milk for adequate foal development. All body systems (e.g., digestive, respiratory, urinary, cardiovascular, and nervous systems and special senses) should receive at least a cursory examination to prevent overlooking of conspicuous problems. Common laboratory tests (Coggin’s test, urinalysis, blood analysis, and fecal egg counts) can be used in conjunction with a physical examination to assess the general health of a mare. Evaluation of conformation for defective traits that are potentially heritable is also prudent.

REPRODUCTIVE EXAMINATION

Restraint

With examination of a mare’s reproductive tract, one must assess the mare’s demeanor and ensure that she is properly restrained. Such precautions prevent or reduce undue injury to the mare or veterinarian during the examination process. Methods of restraint are the same as those discussed for palpation per rectum (see Chapter 1).

Examination of the External Genitalia

The first part of the reproductive examination involves a thorough inspection of the external genitalia. Conformation of the vulva, perineum, and anus is closely evaluated. To prepare the area for examination, the tail can be wrapped in a plastic sleeve, which is itself secured at the base of the tail with tape. The tail is then elevated by lifting it directly over the mare’s rump to improve visualization of the external genitalia (Figure 4-2). Another useful method is to wrap the tail in a gauze bandage, pull the tail up to the side, and tie the gauze around the mare’s neck. The disadvantage of this method is that exposure of the perineal area is reduced; however, it is useful for keeping the tail out of the way when a stock is not available.

The long axis of the vulva should be vertical, with the vulvar labia well apposed to produce an intact vulvar seal against contamination (see Figure 1-11). Any conformational abnormalities or vulvar discharge are noted. The perineum should be intact, and the anus should not be recessed (sunken) (see Figure 1-12) because this conformation predisposes the mare to excessive vulvar contamination during defecation. The labia of the vulva can be parted gently to document that the mare has an intact vestibulovaginal seal. If the vestibulovaginal seal is incompetent, parting the vulvar lips results in aspiration of air, heard as a sucking noise. This seal is also important to deter ascending uterine infection.

Palpation per Rectum

With the arm protected with a plastic sleeve, a veterinarian can palpate the internal genital organs of the mare. With use of a systematic approach, the cervix, uterus, and ovaries are evaluated for normalcy. The uterus should be examined for evidence of pregnancy before more thorough palpation. If the mare is determined to be nonpregnant, the examination is continued. (Ultrasonographic evaluation is covered in Chapter 5.)

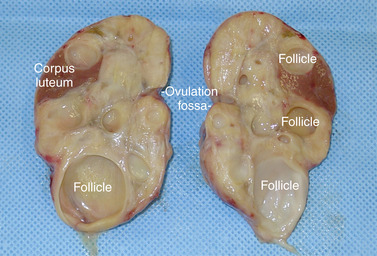

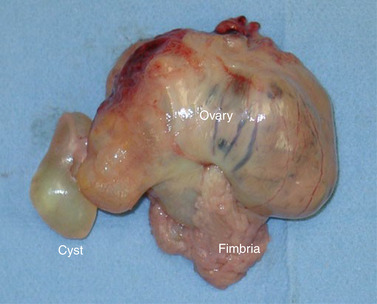

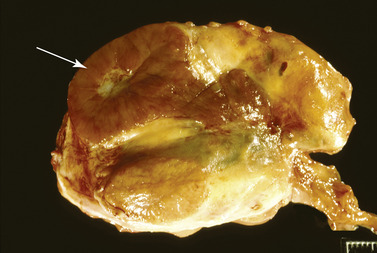

The ovaries of the mare are generally bean-shaped and range in size from that of a golf ball to a tennis ball (see Chapter 1). The ovulation fossa can be readily palpated in the normal ovary. Mares can have ovarian tumors develop that result in substantial increase in ovarian size and loss of the ovulation fossa (Figure 4-3). Ovarian size can also be markedly increased with hematoma formation (Figure 4-4), which occurs when excessive bleeding follows ovulation and formation of a corpus hemorrhagicum. The ovaries are examined for follicles (Figure 4-5) or corpora lutea (Figure 4-6), findings that suggest that the mare is having normal estrous cycles. Occasionally, incidental parovarian cysts are detectable but seldom interfere with fertility. Cysts formed in the fossa region are thought to be peritoneal fragments that become embedded in the serosal surface of the ovary after ovulation. Other parovarian cysts are likely to be distended remnants of the embryonic mesonephric system or paramesonephric tubules or ducts and are located at the mesovarium near the ovary (Figure 4-7) or on the ovary (epoophoron). Very small (1 to 2 cm in diameter) hypoplastic ovaries are sometimes found bilaterally, in which case gonadal dysgenesis as a result of sex chromosome abnormalities should be suspected. If one ovary is enlarged and the other is small and inactive, a granulosa cell tumor involving the enlarged ovary should be suspected. Sometimes, one or both ovaries may be absent. If only one ovary is missing, it was likely removed previously because of an ovarian tumor. Some performance mares have both ovaries surgically removed in an attempt to eliminate objectionable behavior associated with estrus. If an ovariectomized mare is sold, the new owner may be unaware that the ovaries have been removed.

|

| Figure 4-6 (Photo courtesy of Dr. John Edwards.) |

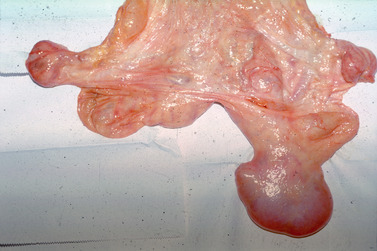

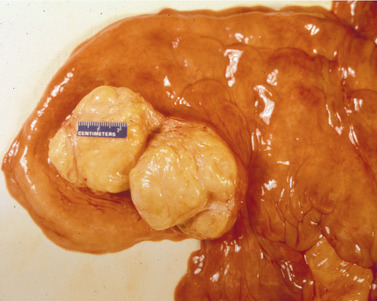

The uterus of the nonpregnant mare is T (or Y) shaped, consisting of two uterine horns and a singular uterine body (see Chapter 1). It is palpated in its entirety for size, symmetry between uterine horns, and evidence of luminal contents. Numerous uterine abnormalities can be detected via palpation per rectum and include atrophy of endometrial folds (Figure 4-8), localized atrophy of uterine musculature, large lymphatic cysts (Figure 4-9), uterine tumors (Figure 4-10), and presence of large quantities of purulent material or other abnormal fluid within the lumen of the uterus (Figure 4-11).

|

| Figure 4-10 < div class='tao-gold-member'> Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|