PART THREE Determines abnormalities in the intrinsic coagulation pathway Prolonged with deficiencies in factors VIII, IX, XI, and XII and fibrinogen; also prolonged with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) Prolonged with von Willibrand disease, acquired vitamin K deficiency, coumarin poisoning, bile insufficiency, liver failure Severely prolonged with hemophilia A (factor VIII deficiency) and hemophilia B (factor IX) Elevated in: pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism Decreased in: iatrogenic Cushing syndrome and adrenal tumors Feline: 4.5–15.0 μg/dL (13–16 μg/dL: suggestive of hyperadrenocorticism, >16 μg/dL strongly suggestive) Canine: 5.5–20.0 μg/dL (18–24 μg/dL: suggestive of hyperadrenocorticism, >24 μg/dL strongly suggestive) From 15% to 20% are false-negative results; false-positive results may be seen with stress or nonadrenal illness. Pre-ACTH cortisol is in normal range, and post-ACTH cortisol shows little to no change with iatrogenic Cushing syndrome. Pre-ACTH cortisol is below normal, and post-ACTH cortisol shows little change with hypoadrenocorticism. Pre-ACTH and post-ACTH cortisol levels should be between 1 and 5 μg/dL with successful Lysodren induction or while on maintenance Lysodren therapy. Trilostane induction: <1.45 μg/dL, stop treatment. Restart on a lower dose. 1.45–5.4 μg/dL, continue on same dose. 5.4–9.1 μg/dL, continue on current dose if clinical signs well controlled or increase dose if clinical signs of hyperadrenocorticism still evident. Elevated in: hepatocellular membrane damage and leakage Inflammation: chronic active hepatitis, lymphocytic/plasmacytic hepatitis (cats), enteritis, pancreatitis, peritonitis, cholangitis, cholangiohepatitis Infection: bacterial hepatitis, leptospirosis, feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), infectious canine hepatitis Toxicity: chemical, heavy metals, mycotoxins Neoplasia: primary, metastatic Endocrine: diabetes mellitus, hyperadrenocorticism, hyperthyroidism Hypoxia: cardiopulmonary disease, thromboembolic disease Metabolism: feline hepatic lipidosis, storage diseases (e.g., copper) Decreased in: end-stage liver disease, but in most cases decreased ALT is not significant Reported as a titer, very laboratory dependent. Refer to your laboratory for normal ranges. High positive titer, with associated clinical and clinicopathologic signs, supports a diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Many immune-mediated, inflammatory, and infectious diseases and neoplasms can result in low positive titers. Results may be false negative with chronic glucocorticoid use. Right-left shunts (patent ductus arteriosus, ventricular septal defects, intrapulmonary shunts) Ventilation/perfusion mismatch (various pulmonary diseases) Hypoventilation (anesthesia, neuromuscular disease, airway obstruction, central nervous system disease, pleural space or chest wall abnormality) Decrease in fraction of inspired oxygen (hooked up to empty oxygen tank) Elevated (basophilia) in: disorders associated with IgE production/binding (heartworm disease, atopy), inflammatory disease (gastrointestinal tract disease, respiratory tract disease), neoplasia (mast cell neoplasia, basophilic leukemia, lymphomatoid granulomatosis), associated with hyperlipoproteinemia and possibly hypothyroidism Elevated in: metabolic alkalosis (with compensatory acidosis) Decreased in: metabolic acidosis Elevated in: metabolic alkalosis Decreased in: metabolic acidosis (with compensatory alkalosis) Elevated in: primary hyperparathyroidism; renal failure; hypoadrenocorticism; hypercalcemia of malignancy (lymphosarcoma, apocrine gland adenocarcinoma, carcinomas [nasal, mammary gland, gastric, thyroid, pancreatic, pulmonary]; osteolytic [multiple myeloma, lymphosarcoma, squamous cell carcinoma, osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma]); hypervitaminosis D (cholecalciferol rodenticides, plants, excessive supplementation); dehydration; granulomatous disease (systemic mycosis [blastomycosis], schistosomiasis, feline infectious peritonitis [FIP]); nonmalignant skeletal disorder (osteomyelitis, hypertrophic osteodystrophy [HOD]); iatrogenic disorder (excessive calcium supplementation, excessive oral phosphate binders); factitious disorders (serum lipemia, postprandial measurement, young animal); laboratory error; idiopathic (cats) Infectious central nervous system (CNS) disease: increased white blood cells (WBCs) and protein content Inflammatory CNS disease: increased WBCs and protein content Brain neoplasia: normal to mild elevation of WBCs, mild elevation of protein content Hydrocephalus, lissencephaly: normal WBCs and protein content Degenerative myelopathy, intervertebral disk disease, polyradiculoneuritis: normal WBCs and normal to mildly increased protein content Most common cause of RBCs in CSF is contamination during collection. Often changes proportionally with sodium. In those cases it is usually easier to search for the cause of the sodium change. Total white blood cell (WBC) count: Total red blood cell (RBC) count: Hematocrit (packed cell volume): Mean corpuscular volume (MCV): Mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH): Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC): Elevated in: stress (environmental, illness), drugs (prednisone and prednisolone [may cross-react in assay], anticonvulsants), pituitary- and adrenal-dependent hyperadrenocorticism Decreased in: drugs (suppression of adrenal function), hypoadrenocorticism Elevated in: azotemia (prerenal, renal, postrenal, rhabdomyolysis) Decreased in: any condition that causes decreased muscle mass • Macrokaryosis—increased nuclear size. Nuclei larger than 20 μ suggestive of neoplasia • Inceased nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio (N:C)—normal nonlymphoid cells have usually have a N:C of 1.3:1.8. Ratios of 1.2 or less suggestive of malignancy • Anisokaryosis—variation in nuclear size. Especially important if the nuclei of multinucleated cells vary in size • Multinucleation—especially important if the nuclei vary in size • Increased mitotic figures—mitosis is rare in normal tissues • Abnormal mitosis—improper alignment of chromosomes • Coarse chromatin pattern—may appear ropy or cord-like • Nuclear molding—deformation of nuclei by other nuclei within the same cell or adjacent cells • Macronucleoli—nucleoli are increased in size (>5 μ suggestive of malignancy, for reference, RBCs are 5–6 μ in the cat and 7–8 μ in the dog • Angular nucleoli—fusiform or have other angular shapes instead of their normal round to slightly oval shape • Anisonucleoliosis—variation in nucleolar shape or size (especially important if the variation is within the same nucleus) • Present individually in tissues, not adhered to other cells for connective tissue matrix • Most discrete cells are of hematogenous origin. • Aspirates of normal lymphoid tissues like spleen and lymph nodes yield discrete cells. • Discrete cell patterns in other tissues indicate the presence of a discrete cell tumor (round cell tumor). Benign tumors of dendritic cell origin, common in young dogs • Medium sized cells, round to oval nuclei that may be indented. Finely stippled chromatin with indistinct nucleoli. Moderate amount of light blue-gray cytoplasm • Most histiocytomas regress spontaneously. The presence of small lymphocytes with these tumor cells may be seen in tumors that are regressing. Cytologic appearance varies from benign looking cells to populations of histiocytic cells with marked atypia. • Common features include large discrete cells with abundant vacuolated cytoplasm, prominent cytophagia, and multinucleation. May demonstrate marked anisocytosis, anisokaryosis, and variation of nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio. Macrocytosis, karyomegaly, and large multinucleated cells are common. • Definitive diagnosis may not be possible based on cytology alone. Tumors of plasma cell origin include multiple myeloma (arising primarily from bone marrow) and extramedullary plasmacytomas (usually cutaneous but may be in other sites such as GI). • Cutaneous plasmacytomas are usually benign. GI tumors are more likely to be malignant. • Well-differentiated plasmacytomas yield cells that resemble normal plasma cells. Small, round nuclei with deeply basophilic cytoplasm exist with or without the characteristic paranuclear clear zone. Poorly differentiated plasmacytoma cells are less distinct and demonstrate significant criteria of malignancy. Binucleate and multinucleate cells are common in both well and poorly differentiated plasmacytomas. This and a lack of lymphoglandular bodies help differentiate these tumors from lymphosarcoma. TVT cells are typically more pleomorphic than other discrete cell tumors. • Moderate smoky to light blue cytoplasm, numerous cytoplasmic vacuoles that may also be found extracellularly. Nuclei show moderate to marked anisokaryosis and have coarse nuclear chromatin. Nucleoli may be prominent and mitotic figures are common.

Laboratory Values and Interpretation of Results

Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (APTT)

Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH), Endogenous

Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH) Stimulation Test

Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT, Formerly SGPT)

Antinuclear Antibody (ANA)

Arterial Blood Gases

Canine

Feline

pH

7.35–7.45

7.36–7.44

PaCO2

36–44

28–32

PaO2

90–100

90–100

TCO2

25–27

21–23

HCO−3

24–26

20–22

Potential causes of hypoxemia

Basophil Count

Bicarbonate (HCO3−)

Calcium (Ca)

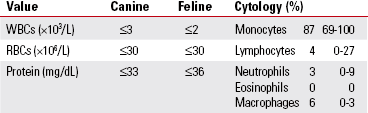

Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF)

Chloride (Cl)

Corrected Hyperchloremia (elevation of chloride disproportionate to elevation of sodium):

Complete Blood Count (CBC)

Cortisol

Creatinine

Cytologic Criteria of Malignancy

Nuclear Criteria

Cytologic Features of Discrete Cell (Round Cell) Tumors

Specific Discrete Cell Tumors

Lymphoma

Canine Cutaneous Histiocytoma

Malignant Histiocytosis/Histiocytic Sarcoma/Systemic Histiocytosis

Plasmacytoma

Transmissible Venereal Tumor

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree