CHAPTER 18. Evaluation of Breeding Records

OBJECTIVES

While studying the information covered in this chapter, the reader should attempt to:

■ Understand the costs associated with reduced fertility of stallions.

■ Understand how to gather relevant information from breeding farm records.

■ Understand how to evaluate data garnered from breeding farm records.

■ Understand how to interpret the results of the breeding farm record evaluation.

■ Understand how to use daily breeding records to aid with breeding management decisions for stallions.

STUDY QUESTIONS

1. Discuss economic losses associated with low pregnancy and foaling rates in equine breeding operations.

2. Define the term seasonal pregnancy rate, and explain its use and limitations for assessment of fertility.

3. Define the term cycles/pregnancy, and explain how it is used to assess fertility.

4. Explain the makeup of a stallion’s book of mares, and discuss how it influences pregnancy rates.

5. Discuss factors that influence whether a mare becomes pregnant when bred to a given stallion.

ECONOMIC IMPACT OF LOWERED FERTILITY

A stallion that achieves suboptimal pregnancy rates greatly increases the cost of producing foals for mare owners and farm management. The increased costs associated with a stallion’s lowered fertility arise from (1) increased mare expenses (e.g., extra covers, extra transport of mares to breeding sheds, extra veterinary examinations and treatments, and additional boarding fees for mares left at a breeding farm or facility over repeated estrous cycles); (2) wasted maintenance costs associated with support of mares that do not produce foals; (3) decreased income (e.g., from sale of penalized late-born foals that arise from mares not becoming pregnant early in the year, lost income from failure to produce a foal, and lost income from nonproductive stud fees); and (4) labor associated with rebreeding mares and potentially lost service opportunities for the stallion, which could have been breeding another mare. Thus, the economic impact associated with breeding of a stallion with lowered fertility can be substantial.

The following example is used to further illustrate the magnitude of losses that can occur with just a 20% difference in pregnancy rate (Table 18-1). If a stallion breeds a book of 100 mares (with an estimated 1.1 breedings per cycle; a conservative 10% double rate) and achieves a 60% pregnancy rate per cycle over a total of three estrous cycles, the stallion has a 93% seasonal pregnancy rate, necessitating a total of 172 covers. If 85% of the pregnancies (assuming a 15% embryonic and fetal loss rate) result in live foals, 79 foals are produced. By contrast, if only a 40% pregnancy rate per cycle is achieved, the stallion has a 78% seasonal pregnancy rate, necessitating a total of 216 covers. If 85% of the pregnancies result in live foals, 66 foals are produced. The lower fertility culminates in an extra 44 covers (40 estrous cycles × 1.1 covers/cycle) that necessitate board and veterinary expense over the course of the breeding season yet produce 13 fewer foals and an additional 13 years of nonproductive maintenance expense (13 additional barren mares). If the boarding fee at the breeding farm is $26/day, the 40 extra estrous cycles of breeding (21 days/cycle) result in an extra cost of $21,840 over that for the higher level of fertility. If veterinary fees average $250 for examinations and treatments per cycle, the 40 extra estrous cycles of breeding result in increased veterinary fees of $10,000 over that for the higher level of fertility. If transport fees for the mare to the breeding shed are $150 per round trip, the cost of transport fees for 44 extra trips totals $6,600. The added cost of the lower fertility in this example totals $38,440, yet does not include lost income from 13 stud fees, the maintenance expenses for 13 additional barren mares for 1 year, or lost income from 13 foals that are not produced or labor costs associated with the farm where the stallion is, or even the lost opportunity in breeding another mare when the stallion is heavily booked and may need separation of services to breed three times or more per day. Although expenses, fees, and sales prices vary, this example serves to stress the importance of maximizing reproductive efficiency of the stallion.

| Influence of two (40%, 60%) theoretical PRs/cycle on number of covers needed to complete three estrous cycles of breeding and seasonal pregnancy rate (SPR) for a stallion mated to 100 mares with natural cover. | |

| Assuming 1.1 covers (i.e., 10% double rate) are needed per estrus and 85% of pregnancies result in production of viable foals (i.e., 15% pregnancy loss rate), the lower level of fertility would result in 44 extra covers (40 extra cycles) throughout the season yet produce 13 fewer foals (i.e., 13 more barren mares). | |

| No. Mares Bred per Cycle × Theoretical PR/Cycle × Covers/Cycle = No. Mares Pregnant | No. covers |

|---|---|

| Lower Theoretical Fertility | |

| 100 mares bred 1st cycle × 40% PR/cycle × 1.1 covers/cycle = 40 mares pregnant on 1st cycle | 110 covers |

| 60 mares bred 2nd cycle × 40% PR/cycle × 1.1 covers/cycle = 24 mares pregnant on 2nd cycle | 66 covers |

| 36 mares bred 3rd cycle × 40% PR/cycle × 1.1 covers/cycle = 14 mares pregnant on 3rd cycle | 36 covers |

| Total mares pregnant after 3 cycles of breeding = 78 | Total no. covers for season = 216 covers |

| No. foals produced = 78 − (78 × 15% loss rate) = 66 | |

| No. barren mares = 34 mares | |

| Higher Theoretical Fertility | |

| 100 mares bred 1st cycle × 60% PR/cycle × 1.1 covers/cycle = 60 mares pregnant on 1st cycle | 110 covers |

| 40 mares bred 2nd cycle × 60% PR/cycle × 1.1 covers/cycle = 24 mares pregnant on 2nd cycle | 44 covers |

| 16 mares bred 3rd cycle × 60% PR/cycle × 1.1 covers/cycle = 9 mares pregnant on 3rd cycle | 18 covers |

| Total mares pregnant after 3 cycles of breeding = 93 | Total no. covers for season = 156 covers |

| No. foals produced = 93 − (93 × 15% loss rate) = 79 | |

| No. barren mares = 21 | |

SOME FACTORS THAT AFFECT STALLION FERTILITY

Achievement of suboptimal pregnancy rates remains a serious problem within the horse industry. The veterinarian must remain cognizant that many factors contribute to the overall fertility of a stallion, including: inherent fertility of the stallion, inherent fertility of the mares bred by the stallion, and quality of management (e.g., nutrition and body condition, teasing and breeding management, level of veterinary care). Each contributing factor is capable of severely constraining the percentage and number of offspring produced each year by a given stallion. It should therefore not be assumed that lowered pregnancy rates must result from a problem with stallion fertility unless record analyses and examination findings, along with a thorough evaluation of mating practices, support this conclusion. To this end, examination of fertility from stallions on the same breeding farm during the same time period is often useful.

Investigation of suboptimal fertility achieved by a stallion should be directed toward identification and correction of contributing factors. In some cases, treatment of a disease condition (e.g., infection, ejaculatory dysfunction; see Chapter 16) may improve the stallion’s fertility. In other cases, no treatment is indicated for the stallion, yet the reduced reproductive quality of the mares in his book precludes significant improvement in fertility. More commonly, recommendations for alterations in breeding management practices can be identified that might improve the stallion’s fertility. The search for causes of suboptimal fertility should begin with record analysis to fully characterize a stallion’s breeding performance.

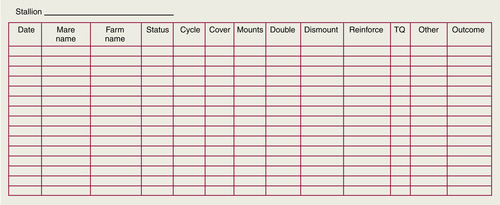

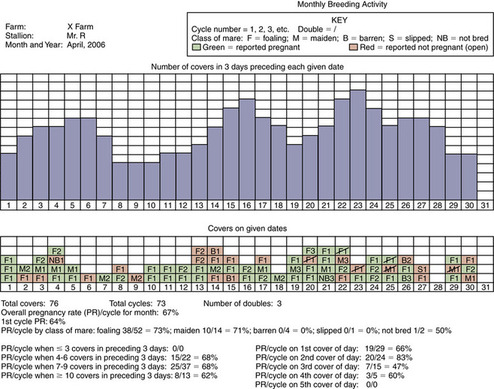

Breeding records should be the most detailed, objective historic information that the clinician can obtain. Breeding records exist in many forms that range from poorly organized handwritten papers to highly organized computerized spreadsheets listing numerous mathematic parameters. However, even computerized record-keeping programs usually remain inadequate for summarizing and measuring relevant fertility endpoints, and further collation and analysis are needed for accurate assessment of breeding performance. Figures 18-1 and 18-2 are examples of breeding records that are sometimes used for Thoroughbred stallions; they can easily be adapted for stallions used in artificial breeding programs. They consist of a chronologic breeding sheet (see Figure 18-1) for recording of pertinent information obtained from each mating and a graphic summary of mares mated in a given month (see Figure 18-2). The monthly breeding sheet is used to summarize various reproductive endpoints as pregnancy outcome from breeding becomes known.

The clinician should not hesitate to request breeding records from previous breeding seasons and the current breeding season to facilitate determination of whether the fertility of a stallion has changed. A stallion’s fertility can change from year to year simply because of the reproductive quality of the mares in his book (Table 18-2). A decrease in the quality of mares bred commonly follows a decline in the stallion’s popularity. As the stallion’s stud fee drops, the owner or manager must accept mares of lesser reproductive quality to fill the stallion’s book (Table 18-3).

| Seasonal pregnancy rate (PR/season) declined from 86% to 75%, and overall pregnancy rate/cycle (PR/cycle) declined from 66% to 57%. The lower than expected seasonal pregnancy rate in the second year most likely resulted from two problems that are apparent from examining the records: (1) low fertility in the barren mare group in year 2, which comprised one fourth of his book (note that the PR/cycle was quite good in other classes of mares in year 2 and comparable in foaling and maiden mares, typically the most fertile classes of mares, in both years); and (2) insufficient opportunity to rebreed mares that did not become pregnant. In this regard, note that only 53 cycles were used to cover the total book of 40 mares in year 2. The PR/cycle among other (than barren) classes of mares in year 2 varied from 67% to 73%; thus, if more opportunities had existed for covering those mares not becoming pregnant in the first cycle in those groups, seasonal pregnancy rate might not have been so low. | ||||||

| Year | Class of Mare | No. Bred | No. Pregnant | No. Cycles | PR/Cycle | PR/Season |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Barren | 6 | 6 | 9 | 67% | 100% |

| Foaling | 49 | 42 | 59 | 71% | 86% | |

| Maiden | 4 | 4 | 5 | 80% | 100% | |

| Not Bred | 3 | 3 | 4 | 75% | 100% | |

| Slipped | 9 | 6 | 15 | 40% | 67% | |

| Total | 71 | 61 | 92 | 66% | 86% | |

| 2 | Barren | 10 | 5 | 18 | 28% | 50% |

| Foaling | 16 | 13 | 18 | 72% | 81% | |

| Maiden | 9 | 8 | 11 | 73% | 89% | |

| Not Bred | 3 | 2 | 3 | 67% | 67% | |

| Slipped | 2 | 2 | 3 | 67% | 100% | |

| Total | 40 | 30 | 53 | 57% | 75% | |

| The book of mares is small, which limits conclusions that can be made about the stallion’s inherent fertility. Although the overall pregnancy rate (PR) per cycle was only 53%, his first cycle PR achieved in foaling mares was 73% (14/19). Of the rest of his book of mares, only one (slipped) mare became pregnant on the first cover. This finding suggests if the stallion had a larger book of mares, of which more were known to be fertile (e.g., foaling mares), he could achieve better overall PRs per cycle and per season. | ||

| Class of Mare | PR/Season | PR/Cycle |

|---|---|---|

| Barren | 2/3 (67%) | 2/7 (29%) |

| Foaling | 19/22 (86%) | 19/32 (59%) |

| Slipped | 2/2 (100%) | 2/4 (50%) |

| All Classes | 23/27 (85%) | 23/43 (53%) |

EVALUATION OF BREEDING FARM RECORDS

This exercise is intended to introduce the reader to the breeding records that may be available on breeding farms that have stallions standing at stud. Keep in mind that the stallion owner or the manager may not keep data regarding each mating, leaving a conclusion to be drawn about a stallion’s “subfertile” condition solely from results of semen evaluation. Analysis of the breeding records should be considered as much a part of the breeding soundness evaluation as other components of the examination.

Table 18-4 provides an example of a typical breeding record. Records may also be provided as day-to-day worksheets that have not been tabulated. The information that is commonly recorded is listed across the top of the table and includes the following:

| Mare | Begin Status | Date Foaled | Dates Bred | Days since Last Breeding | Status after Last Examination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Betty | Slipped | 2/26/00 | 258 | In-foal | |

| Suzy | Maiden | 2/29/00 | 255 | In-foal | |

| Kelly | In-foal | 2/14/00 | 3/20/00 | 235 | Barren |

| 2/24/00 | |||||

| 2/22/00 | |||||

| Konnie | In-foal | 3/12/00 | 4/20/00 | 204 | In-foal |

| 4/1/00 |

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree