CHAPTER 16. Surgery of the Stallion Reproductive Tract

OBJECTIVES

While studying the information covered in this chapter, the reader should attempt to:

■ Acquire a working knowledge of the types of reproductive disorders of stallions that can be corrected with surgery.

■ Acquire a working understanding of the surgical procedures or treatments used to correct disorders of the stallion genital tract.

STUDY QUESTIONS

1. Discuss indications, techniques, and potential postoperative complications of castration of stallions.

2. Discuss methods used to diagnose and correct cryptorchidism in stallions.

3. Describe the surgical procedures or treatments that can be used for the following disorders:

a. Inguinal herniation

b. Torsion of the spermatic cord

c. Hydrocele

d. Hematocele

e. Testicular neoplasia

f. Penile and preputial injuries

g. Paraphimosis/penile paralysis

h. Phimosis

i. Neoplasia of the penis and prepuce

j. Cutaneous habronemiasis

k. Priapism

l. Hemospermia and hematuria

CASTRATION

Orchiectomy, castration, emasculation, gelding, and cutting are terms for surgical removal of the testes. Castration is one of the most commonly performed equine surgical procedures, and its complications are among the most common causes of malpractice claims against veterinarians.

General Considerations

Castration prevents or decreases objectionable sexual behavior and aggressive temperament and prevents stallions of inferior quality from reproducing. Castration removes the major source of circulating androgens and estrogens responsible for male sexual behavior. Castration may be indicated for removal of a testicular tumor or because one or both testes have been irreparably damaged. During repair of an inguinal (or scrotal) hernia, the ipsilateral testis is usually removed.

Horses can be castrated at any age, but the age at which a horse is castrated is usually determined by managerial convenience. Most horses are castrated when they are between 1 and 2 years old, when objectionable sexual behavior most commonly commences. The operation may be delayed until male characteristics develop or until the owner can determine whether the horse may have value as a sire. Castration before puberty may delay closure of the growth plates of the long bones, causing the horse to grow to a height greater than it would have had it not been castrated.

Before the horse is castrated, its scrotal region should be inspected closely to document the presence of two normal scrotal testes and the absence of an inguinal (or scrotal) hernia. The scrotal region should be palpated after the horse is sedated, if the region cannot otherwise be palpated safely. The absence of either testis or detection of intestine in the inguinal canal (or scrotum) may alter the method of anesthesia or the technique of castration.

Orchiectomy may be performed with the open, closed, or half-closed technique, regardless of whether the horse is castrated while standing or recumbent. With the open technique of castration, the parietal (or common vaginal) tunic is not excised, but with the closed and half-closed techniques of castration, the portion of the parietal tunic that surrounds the testis and distal portion of the spermatic cord is excised along with the testis.

Several different emasculators are available for equine castration. Some of the more commonly used emasculators are shown in Figure 16-1; individual preference governs which one is used. We prefer the Reimer emasculator.

|

| Figure 16-1 (From Varner DD, Schumacher J, Blanchard TL, et al: Diseases and management of breeding stallions, St Louis, 1991, Mosby.) |

Both tetanus antitoxin and tetanus toxoid should be administered to the horse before or after castration, if the horse has not been previously immunized with tetanus toxoid. A tetanus toxoid booster should be given to a previously vaccinated horse if more than a year has elapsed since the horse was vaccinated. Prophylactic antimicrobial therapy is usually not necessary, provided that the horse is castrated with aseptic technique and the horse’s surroundings are clean, but a survey of practitioners to determine factors that influence the incidence of complications associated with castration indicated that infection may be less likely to develop at the site of surgery if horses receive perioperative antimicrobial treatment.

The castrated horse should be confined to a clean stall for the first 24 hours after surgery to diminish the likelihood of hemorrhage from the severed spermatic vessels. Thereafter, the horse should be exercised to the degree necessary to prevent excessive preputial and scrotal edema. A typical regimen of exercise is 15 minutes of vigorous activity twice daily for 10 days. Although the ejaculate is unlikely to contain enough viable sperm to permit impregnation 1 week after castration, the horse should be isolated from mares for at least 2 to 3 weeks to avoid copulation. Abdominal forces during copulation could allow viscera to traverse a vaginal ring.

Castration in Lateral Recumbent Position

A variety of safe, short-term anesthetic agents can be administered intravenously, alone or in combination, to induce a recumbent position for castration. Thiopental, an ultra–short-acting thiobarbiturate, used alone or after administration of an α-2 agonist (e.g., detomidine HCl, xylazine HCl, or romifidine) provides a short period of general anesthesia but no analgesia. When used with an alpha-2 agonist, muscular relaxation is satisfactory. Recovery usually is satisfactory if only a single dose of thiopental is administered. Guaifenesin (5% to 10%) in combination with thiopental or ketamine HCl (with xylazine administered as a preanesthetic agent) provides good analgesia with smooth induction and recovery. This combination can also be used as a constant-rate infusion, if the length of anesthesia must be extended. Other anesthetic drug combinations include the standard xylazine-ketamine regimen, with the addition of butorphanol or valium. The use of the neuromuscular blocking agent succinylcholine alone to provide restraint during castration is inhumane because the drug provides no analgesia or sedation.

After general anesthesia is induced, the horse is positioned in a lateral recumbent position with the upper hind limb drawn cranially toward the shoulder by a loop of rope, encircling the pastern and hock that extends from another loop of rope encircling the base of the neck. The rope maintains the hind limb in a flexed position (Figure 16-2). For the right-handed operator, the castration is most easily performed with the horse in left lateral recumbent position.

The scrotum and sheath are prepared for aseptic surgery. Removal of the bottom of the scrotum (Figure 16-3) to expose the testes provides better drainage, resulting in fewer complications, than if the testes are exposed through an incision over each scrotal sac. For removal of the bottom of the scrotum, traction is placed on the scrotal raphe, and the tented tissue is excised with careful dissection with a scalpel. To avoid transection of large vessels, dissection should be relatively superficial through the scrotal fascia as opposed to cutting straight across the tented tissue. Alternatively, the median raphe can be tensed by pulling the cranial end of the sheath forward and upward with one hand while making a longitudinal incision on each side of the median raphe with a scalpel in the other hand (Figure 16-4). The incision is extended through the skin, tunica dartos, and underlying scrotal fascia. If an open technique of castration is used, the common vaginal (parietal) tunic of each testis is also incised. The skin between the two incisions can be excised to provide better drainage (Figure 16-5).

When an open technique of castration is used, the common vaginal (parietal) tunic is not removed. Instead, the common vaginal tunic is incised, and the caudal ligament of the epididymis (a remnant of the gubernaculum), which affixes the common vaginal tunic to the epididymal tail and attached testis, is severed. The spermatic vessel and ductus deferens are transected close to the superficial inguinal ring with an emasculator.

When a closed castration technique is used, the common vaginal tunic is not opened, except at the point at which the spermatic cord is transected. The common vaginal tunic, its contents (i.e., the testis, epididymis, and spermatic cord) and attached cremaster muscle are freed from the surrounding scrotal fascia with blunt dissection and removed by transecting the cord and attached cremaster muscle close to the superficial inguinal ring with an emasculator. The closed technique of castration can be modified (i.e., the modified-closed technique of castration) with a longitudinal incision, 3 to 4 cm long, in the common vaginal tunic proximal to each testis (Figure 16-6). The left thumb (of a right-handed operator) is inserted through the incision into the vaginal cavity and traction is applied to the tunic with the thumb while the fingers of the left hand force the epididymis and testis through the incision (Figure 16-7). Because the ligament of the tail of the epididymis affixes the fundus of the common vaginal tunic to the epididymis and attached testis, the fundus inverts and follows the testis through the incision (Figure 16-8). The left index and middle fingers are placed into the inverted fundus to maintain tension on the common vaginal tunic, and the left thumb is wrapped around the spermatic cord firmly to assist in traction. The spermatic cord and attached cremaster muscle are bluntly dissected free from scrotal fascia and transected near the superficial inguinal ring with an emasculator. By opening the common vaginal tunic, this modified-closed, or half-closed, technique of castration allows observation of all enclosed structures (i.e., testes, epididymis, ductus deferens, and spermatic vessels).

Because the common vaginal tunic is removed with closed and modified-closed castrations, the likelihood of infection of the spermatic cord and of formation of a hydrocele is decreased. If the horse has a scrotal or inguinal hernia, use of the closed technique of castration and placement of a ligature around the spermatic cord proximal to the site of transection prevent evisceration. The closed or modified-closed technique is indicated when the condition for which the horse is being castrated involves the common vaginal tunic. Such a condition could include neoplasia, periorchitis, and torsion of the spermatic cord.

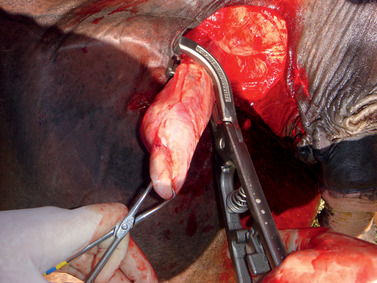

Proper application of an emasculator that is in good working order is crucial to successful castration. The jaws of the emasculator are placed around the distal end of the spermatic cord, if the castration is closed (Figure 16-9), or around the contents of the spermatic cord, if the castration is open. The jaws are closed tightly enough to prevent inclusion of skin in the emasculator’s jaws but loosely enough to allow proximal movement of the emasculator to the site of transection near the superficial inguinal ring. The emasculator must be applied with the crushing portion of the instrument positioned proximal to the cutting portion. That is, the wing nut of the emasculator is directed toward the testis (“nut-to-nut” configuration). Tension on the spermatic cord is released before transection. To promote satisfactory hemostasis, the spermatic cord should be divided transversely rather than tangentially, and the emasculator should be left in place for 30 to 60 seconds, depending on the size of the cord. If the cord is large, the ductus deferens and spermatic vessels can be separated from the common vaginal tunic and cremaster muscle and the two components transected separately.

Fascia or tunic that could protrude from the scrotal incision when the horse stands should be removed with scissors. The scrotal wound is usually left unsutured to allow drainage, but the wound can be sutured to permit healing by first intention, provided that orchiectomy has been performed aseptically. Complete hemostasis is necessary when the scrotal incision is primarily closed, so a ligature should be placed around the cord proximal to the intended point of transection, before the spermatic cord is transected with emasculators. The skin incision is closed with synthetic absorbable suture material with a continuous intradermal pattern. No attempt is made to close dead space.

The use of the Henderson castrating instrument (Stone Manufacturing & Supply Co, Kansas City, Mo.) has been gaining popularity among equine practitioners. The instrument is used in combination with a standard 14.4-V, variable-speed cordless hand drill; it was originally introduced in 1994 for castration of bulls but was recently redesigned for castration of stallions. Patient preparation and surgical approach are essentially the same as for the closed castration technique with emasculators in the recumbent animal. Instead of emasculators, however, the Henderson instrument, attached to the drill, is clamped to encompass the entire spermatic cord just proximal to the testicle (Figure 16-10). Then, without any tension placed on the cord, the drill is judiciously powered to provide a slow to moderate rotational speed in a clockwise direction. The cord initially shortens as it twists but then elongates just before severance, which usually occurs after 15 to 20 turns. The tight twisting and tearing action seal the spermatic cord and result in hemostasis (Figure 16-11). The second testicle is removed in a similar manner. The scrotal incision can be sutured to heal by primary intention or left open to allow drainage. This technique is reported to result in fewer complications than with the use of emasculators.

|

| Figure 16-10 (Courtesy Dr. Cleet Griffin.) |

Castration Performed with the Horse Standing

Standing castration can be performed safely and efficiently if the surgeon is technically proficient, candidates for standing castration are selected prudently, and the spermatic cords and scrotum are desensitized adequately with local anesthetic solution. Sedation or tranquilization for standing castration is optional but strongly recommended. Suitable drugs include an α-2 agonist (e.g., detomidine HCl, xylazine HCl, or romifidine) and butorphanol tartrate. These drugs often are used in various combinations. Acetylpromazine is commonly administered to tranquilize stallions for standing castration or before induction of general anesthesia for castration, but its administration to stallions should be discouraged because it can result, on a rare occasion, in penile paralysis or priapism.

The surgical site is desensitized by infiltrating the subcutaneous scrotal tissue with 10 to 15 mL of local anesthetic solution (e.g., 2% lidocaine HCl or mepivacaine HCl) on each side of the scrotal raphe, followed by deposition of 10 to 15 mL of the anesthetic solution into each spermatic cord. Direct injection into the spermatic cord occasionally causes a hematoma at the site of injection, which may interfere with transection of the cord. Alternatively, 15 to 30 mL of local anesthetic solution can be injected into the parenchyma of each testis and allowed to diffuse proximally into the cord.

Before injection, the scrotal and inguinal areas should be scrubbed thoroughly, and the tail should be wrapped to prevent contamination of the surgical site. Even if the horse has been tranquilized or sedated, a twitch should be applied to its muzzle to prevent the horse from moving when the surgical site is infiltrated with local anesthetic solution. The right-handed surgeon generally works from the left side of the horse, leaning into the horse’s side and avoiding the horse’s kicking range. After the scrotum and spermatic cord are desensitized, a final scrub is applied to the operative site.

The standing horse can be castrated with an open, closed, or modified-closed technique, as described for the recumbent horse. With castration with the horse standing, the risks of general anesthesia are avoided, drug expense is usually less, and the procedure is shorter because no recovery time from general anesthesia is needed. Risks to the surgeon are greater, however, so candidates for the procedure should be selected carefully. Standing castration should be reserved for well-mannered stallions with well-developed scrotal testes and no history of recurrent scrotal swellings. If the testes cannot be palpated easily and safely and are not within the scrotum, the horse should be anesthetized and castrated while recumbent. Donkeys, mules, and small ponies are castrated more easily and safely with general anesthesia.

Laparoscopic Castration

Testes of entire stallions have been removed with a laparoscopic technique with the horse sedated and standing or, if intractable, anesthetized and in dorsal recumbent position. For laparoscopic removal of a scrotal testis, the vaginal ring is incised with scissors, and the testis is retracted into the abdomen with application of traction to the mesorchium. The ligament of the tail of the epididymis is severed, the testicular artery and vein are ligated and divided, and the testis is pulled from the abdomen. The vaginal ring is closed with staples or sutures.

A scrotal testis can also be left in situ and destroyed by disrupting its blood supply with electrocautery or ligation. The epididymis and the outer layer of the tunica albuginea remain viable, but the parenchyma of the testis undergoes avascular necrosis. Although the testis can still be palpated for up to 5 months, it is incapable of producing sperm and hormones. Failure to destroy the testicular parenchyma by disrupting the testicular blood supply, resulting in preservation of stallion-like behavior, has been reported. The advantages of laparoscopic castration include a rapid return of the horse to function and few complications.

Postoperative Complications of Castration

Hemorrhage

Excessive hemorrhage is the most common, immediate, postoperative complication of castration and is often caused by an improperly applied or malfunctioning emasculator. The spermatic vessels, especially the spermatic artery, may not be crushed sufficiently if scrotal skin is included accidentally in the jaws of the emasculator or if the spermatic cord is exceptionally large. The spermatic cords of mature and old stallions often must be transected with the technique known as “double emasculation.” With this technique, the spermatic vessels and deferent duct are isolated from the common vaginal tunic and cremaster muscle and are transected separately with the emasculator.

The scrotal vessels can be lacerated when the practitioner incises the scrotum or excises scrotal fascia. This hemorrhage is usually not serious and stops spontaneously. An excited horse, however, often has increased blood pressure, which could result in excessive hemorrhage from the spermatic artery. For this reason, horses caught with difficulty or after a long pursuit should be allowed to cool down before they are castrated. Similarly, frightened horses should be calmed before the operation. Excessive estrogens produced by grazing some lush pastures also may interfere with hemostasis.

Severe hemorrhage occurs if the emasculator is applied upside down because the cord is severed proximal to the crushed portion. If the blade of the emasculator is too sharp, the spermatic vessels may be severed and retract before they are properly crushed. Severe hemorrhage should be assumed to originate from the spermatic artery.

If blood flow from the spermatic cord does not diminish after the horse stands quietly for 20 to 30 minutes, the severed end of the cord can be grasped with fingers and stretched and a crushing forceps, ligature, or emasculator applied to it. If the horse was castrated while recumbent, the cord is not anesthetized when the horse stands, and the horse is likely to resist attempts to grasp the sensitive, severed spermatic cord. In this case, administration of a sedative (e.g., xylazine HCl or detomidine HCl) and analgesic drug (e.g., butorphanol tartrate) is indicated before the inguinal canal is explored. Intractable horses may have to be anesthetized again. Laparoscopic intraabdominal ligation of the testicular vasculature has been used in standing or anesthetized and recumbent horses to stop excessive hemorrhage after castration.

If the end of the severed spermatic cord is inaccessible, sterile, rolled gauze can be packed tightly through the scrotal incision into the inguinal and scrotal cavities. The skin incision is then closed with closely placed sutures or towel clamps. The pack can usually be removed the next day. If hemorrhage continues despite packing, the hemorrhaging vessel must be located and ligated or crushed, usually with the horse anesthetized.

Intravenous administration of 10 to 15 mL of 10% formalin in 1 L of physiologic saline solution, through a catheter, may promote hemostasis by increasing the rigidity of the red blood cells (RBCs). In one experiment, this dose of formalin decreased coagulation time by 67%. In another evaluation of the effects of intravenously administered formalin on hemostasis, however, no benefit was detected. Although we have noted a dramatic reduction of hemorrhage immediately after administration of formalin in our clinical practice, the safety and efficacy of this treatment have not been established.

Swelling

Swelling of the prepuce and scrotum is expected after castration and, unless excessive, is no cause for alarm. Insufficient exercise after castration results in poor drainage from the open scrotum and promotes excessive scrotal and preputial swelling. Beginning on the day after surgery, the horse should be exercised vigorously every day to promote drainage and to discourage premature closure of the scrotal wound. Turning the horse into a large clean field may aid in controlling swelling but does not guarantee the horse will exercise at a level that is beneficial.

The prepuce can be massaged manually to reduce swelling, provided that the horse tolerates palpation in this area. If the scrotal wound seals prematurely, it should be opened with gentle massage of surrounding scrotal skin or dilated with a gloved finger to remove blood clots or serum from the scrotal cavity. Hydrotherapy may help prevent the scrotal incision from sealing prematurely, thereby decreasing scrotal and preputial edema, but a survey of practitioners conducted to investigate results of techniques of castration indicated that horses that receive hydrotherapy after castration may be prone to infection of the scrotum.

Infection

Postoperative swelling may be caused by bacterial infection of the surgical site. Tissues of the scrotal cavity can become infected because the open incisions expose injured tissue to contamination from the environment. Sepsis of the scrotal tissue usually resolves after systemically administered antimicrobial therapy and establishment of proper scrotal drainage. Forced exercise promotes drainage of septic fluid from the scrotal cavity.

Clostridial infection of castration wounds is particularly catastrophic because it causes toxemia and severe tissue necrosis. Clinical signs vary with the clostridial species involved. Affected horses are usually treated with systemic administration of large doses of penicillin and a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory analgesic agent, supportive therapy, and radical debridement of necrotic tissue from the scrotal wound.

Infection of the spermatic cord, or septic funiculitis, can occur as an extension of a scrotal infection, from repeated crushing of the spermatic cord, or from bacterial contamination of the emasculator or ligature. Signs of septic funiculitis include scrotal swelling, pain, and fever. Antimicrobial treatment, drainage, and hydrotherapy may resolve the infection, but removal of the infected stump is usually necessary, especially if the cord has been ligated.

If an affected horse is not treated, the stump of the cord is likely to remain infected, even though the scrotal wound may heal. The stump may become very large because of excessive formation of fibrous tissue, which contains abscesses that may drain continuously or periodically to the exterior. A hard, chronically infected stump of the spermatic cord is sometimes called a scirrhous cord and can be caused by any pyogenic bacterium. Scirrhous cord caused by Staphylococcus spp. is sometimes termed botryomycosis. Fungi also have been recovered from infected spermatic cords. The scirrhous cord adheres to the scrotal skin, and draining tracts are usually present. The horse may display only mild or no signs of pain when the mass is palpated, and chronically affected horses are usually afebrile. A large scirrhous cord may cause hind limb lameness and, in extreme cases, may be palpable per rectum.

Removal of a scirrhous cord usually results in uncomplicated recovery. The infected cord is removed with the horse anesthetized and in dorsal recumbent position. An incision is made over the mass, and the affected portion of cord, along with a section of normal cord, is exposed. Isolation of the scirrhous cord may be difficult if the infection is long standing because of numerous large vessels that invade the mass. The spermatic cord is transected proximal to the mass with an écraseur or emasculator, and the wound is left open to heal by second intention. Postoperative management is the same as that for routine castration.

Septic Peritonitis

Although reported rarely, septic peritonitis can occur after castration because the cavity of the vaginal process (i.e., the vaginal cavity) communicates with the peritoneal cavity. Extension of infection from the vaginal cavity to the peritoneal cavity (or from the peritoneal cavity to the vaginal cavity) is rare because the funicular portion of the vaginal process is collapsed as it courses obliquely through the abdominal wall. Signs of septic peritonitis include fever, depression, weight loss, tachycardia, hemoconcentration, colic, and constipation or diarrhea. Development of any of these signs after castration may warrant gross and cytologic examination of peritoneal fluid. Results of analysis of peritoneal fluid must be interpreted carefully because nonseptic peritonitis occurs in many horses as a result of castration. Nonseptic peritonitis may be related to postoperative, intraabdominal hemorrhage, because free blood within the peritoneal cavity incites inflammation of the peritoneum. A nucleated cell count in the peritoneal fluid of more than 10,000/mL indicates peritoneal inflammation. Counts of more than 10,000/mL are common for 5 or more days after uncomplicated castration, and counts of more than 100,000/mL are occasionally noted. A diagnosis of septic peritonitis should not be based on a high peritoneal nucleated cell count alone. The presence of degenerate neutrophils or intracellular bacteria in the peritoneal fluid is more indicative of peritoneal sepsis, and when accompanied by clinical signs of septic peritonitis, antimicrobial therapy and lavage of the peritoneal cavity are indicated.

Hydrocele

A hydrocele, also called a vaginocele or water seed, may appear several months after castration as a circumscribed, fluid-filled, painless swelling of the scrotum. The scrotum may appear to contain a testis or may resemble a scrotal hernia. If neglected, the fluid-filled scrotum can become as large as a football. Sterile, clear, amber-colored fluid is obtained via needle aspiration of the scrotum. During ultrasound examination of the scrotum, anechoic to semiechoic fluid is seen within the vaginal tunic. Scrotal enlargement is the result of a slowly increasing collection of fluid within the vaginal cavity. The condition is uncommon, and the specific cause is unknown. Hydrocele can occur in stallions and in castrated horses, but the highest incidence rate of the condition may be in castrated mules. The open technique of castration predisposes the gelding to the condition because with this technique, the vaginal tunic is not removed. Removal of the vaginal tunic in castration of a mule may therefore be prudent. Removal of the vaginal tunic is the treatment indicated for castrated horses in which a hydrocele develops.

Evisceration

Evisceration after castration of a horse with normally descended testes is an uncommon but potentially fatal complication. It may occur up to 1 week after castration but usually happens within hours and may be precipitated by the horse’s attempt to rise from general anesthesia. A horse that eviscerates after castration probably has a preexisting, inconspicuous, inguinal hernia that a preoperative examination failed to reveal. Standardbreds, draught horses, Tennessee walking horses, and American saddlebred horses may be more frequently affected by postoperative evisceration because they have a higher incidence of congenital inguinal herniation.

If intestine appears in the scrotal incision after castration, the horse should be anesthetized immediately. If not, the eviscerated intestine soon becomes contaminated and damaged during the violent struggle that ensues from the accompanying pain. A balanced electrolyte solution should be administered intravenously in amounts adequate to combat hypotensive shock. The horse should be positioned in dorsal recumbent position, and the intestine should be cleaned meticulously with copious amounts of physiologic saline solution or a balanced electrolyte solution. Damaged mesentery and intestine should be repaired or resected, and the eviscerated intestine should be reduced into the abdomen as soon as possible to prevent its vascular supply from being damaged. Intraabdominal traction on the intestine at the vaginal ring through a paramedian or ventral midline celiotomy may be necessary to reduce the eviscerated intestine. If the vaginal sac was not removed at the time of castration or was shredded during reduction of the eviscerated intestine, it is ligated with absorbable suture material and transfixed to the medial crus of the superficial inguinal ring. The superficial ring is then closed with doubled absorbable suture material (no. 2 or 3) with a continuous pattern. The superficial layers of the wound are left unsutured if the wound is grossly contaminated.

As a poor alternative to suturing the superficial inguinal ring, sterile rolled gauze can be packed into the inguinal canal. Care should be taken to avoid introducing the gauze into the abdomen. The gauze is held in position for 48 to 72 hours with suturing of the scrotal incision. The vaginal ring should be palpated per rectum before the gauze packing is removed to confirm that the ring has decreased to a size that is no longer capable of permitting the escape of intestine and to confirm that intestine has not adhered to the pack.

Antimicrobial treatment, administered parenterally, should be initiated, and if signs of septic peritonitis develop, the abdominal fluid should be evaluated. The peritoneal cavity should be lavaged once or twice daily for at least several days with a balanced electrolyte solution if the horse has septic peritonitis develop.

Escape of Omentum

Omentum occasionally escapes through the vaginal ring and scrotal incision after castration. If this occurs, the vaginal ring should be palpated per rectum to determine whether intestine has also exited the vaginal ring. Exposed omentum can be removed with emasculators, usually with the horse standing. Because the omentum plugs the vaginal ring, suturing of the superficial inguinal ring may not be necessary. The horse should not be exercised for 48 hours, to prevent further escape of omentum. If omentum continues to escape through the scrotal incision, the superificial inguinal ring should be sutured with the horse anesthetized.

Continued Stallion-like Behavior

Continued stallion-like behavior is a common complication of castration. Geldings that display stallion-like behavior are sometimes called false rigs. False rigs may display masculine behavior ranging from genital investigation and squealing to mounting and even copulation. False rigs are often said to have been proud cut, indicating that epididymal tissue, responsible for the stallion-like behavior, was left with the horse at the time of castration. It is improbable that the epididymis is partially excised during castration of scrotal testes because the epididymis is closely attached to the testis. In fact, few, if any, false rigs have epididymal tissue. Regardless, the epididymis is incapable of producing androgens, and geldings with epididymal tissue are endocrinologically and behaviorally indistinguishable from geldings without epididymal tissue. Spermatic cord remnants have been removed from false rigs to abolish sexual behavior, but because the cords contain no androgen-producing tissue, the efficacy of this procedure is doubtful.

The plasma concentration of luteinizing hormone is increased after castration in response to a decreasing plasma concentration of testosterone, and this increase in concentration of luteinizing hormone has been postulated to stimulate production of androgens by the adrenal cortex. False rigs, however, have no higher circulating concentrations of testosterone than those in normal quiet geldings, and administration of adrenocorticotropic hormone to false rigs does not increase the plasma concentration of testosterone. Adrenal production of androgens is therefore unlikely to contribute to the persistence of stallion-like behavior after castration.

Because some sexually experienced stallions castrated late in life continue to display masculine behavior, stallion-like behavior in geldings has been attributed to learned behavior. Many false rigs, however, have been castrated as juveniles. A retrospective survey found no difference in the prevalence of stallion-like behavior between horses castrated before puberty and those castrated after puberty. In that study, 20% to 30% of each group displayed stallion-like behavior at least 1 year after castration. Persistent sexual behavior in geldings may therefore be part of the normal social interaction between horses and may be completely independent of the presence of testes. Changes in management or stricter discipline may alleviate sexual behavior or reduce it to a tolerable level.

Immunologic Castration

Stallion-like behavior in an entire stallion (i.e., a stallion with two descended testes) or a cryptorchid stallion can be alleviated temporarily by immunizing the stallion against gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) or luteinizing hormone (LH) to decrease the serum concentration of testosterone. Stallions vary in response to immunization against GnRH or LH, but the usual effects, in addition to diminution of sexual behavior, are a decrease in the concentrations of testosterone and estrogen in the serum, a decrease in the size of the testes, and a decrease in semen quality. Repeated immunization is necessary to maintain sufficient binding titer for complete neutralization of GnRH and inhibition of the reproductive endocrine axis. Although no commercial vaccine against GnRH or LH is currently available in the United States, a vaccine against gonadotropin releasing factor (GnRF or GnRH) is available in Australia (EQUITY, Pfizer Animal Health, West Ride, NSW, Australia), and was recently investigated by Canadian workers for its ability to induce ovarian atrophy and anestrus in cyclic mares. Two injections, administered 4 weeks apart, resulted in almost all treated mares entering anestrus lasting the rest of the breeding season. This vaccine could be a valuable tool for temporarily decreasing undesirable sexual behavior of a stallion that competes in athletic endeavors. Vaccination could be discontinued when the stallion was determined to be suitable for breeding.

CRYPTORCHIDISM

Cryptorchidism is a condition in which one or both testes fail to descend into the scrotum. The undescended testis is termed cryptorchid, and by extension of the term, stallions with one or both testes in a location other than the scrotum are said to be cryptorchid. Other terms for horses with an undescended testis include rig, ridgling, and original. If the testis has passed through the vaginal ring but not the superficial inguinal ring, the horse is termed an inguinal cryptorchid or high flanker. A retractile testis is a testis that can be palpated in the inguinal area but can be manipulated into the scrotum. It should be distinguished from a truly inguinal cryptorchid testis. The retractile testis may reside in a position remote from the scrotum until the horse reaches puberty, when growth of the testis causes the testis to be maintained permanently within the scrotum. A subcutaneous testis that cannot be displaced manually into the scrotum is termed ectopic. The horse is termed a complete abdominal cryptorchid if the testis and epididymis are both within the abdomen. The horse is termed a partial abdominal cryptorchid, if the testis is within the abdomen but a portion of the epididymis lies within the inguinal canal.

A horse with two testes, one descended and one cryptorchid, is sometimes described incorrectly as being monorchid. The term monorchid should be reserved to describe a horse that has only one testis, regardless of that testis’ location. The most common cause of monorchidism is failure of the surgeon to remove both testes at the time of castration, but the condition can also occur from unilateral testicular agenesis or from degeneration of an abdominal testis caused by torsion of its spermatic cord.

Retained testes are aspermic because spermatogenesis is inhibited by elevated temperature. The temperature of the scrotal skin is typically maintained 3°C to 4°C lower than body temperature. Bilateral testicular retention, therefore, results in elevated testicular temperature culminating in germ cell degeneration, testicular atrophy, and sterility. However, because the androgen-producing Leydig cells of cryptorchid testes remain functional (secrete androgens), cryptorchid horses have secondary sexual characteristics and exhibit male sexual behavior.

Cryptorchidism is a sex-limited, complex developmental condition, the cause of which is not completely understood. It is the most common disorder of sexual differentiation in male horses and one of the most common congenital abnormalities in male mammals. In one retrospective study, one of every six 2- to 3-year-old colts referred to 16 North American veterinary university teaching hospitals for medical attention was cryptorchid. The condition was most prevalent in Percherons and least prevalent in Thoroughbreds. Quarter Horses ranked third, behind the Palomino, in relative risk. The mechanisms of testicular differentiation and descent in domestic animals and in men are similar. The details of this process in horses have been studied but remain poorly understood.

Causes of Cryptorchidism

Testicular descent is a complex process, and thus, the causes of abnormal descent are probably varied and difficult to document. Reported mechanical causes of abnormal testicular descent in stallions include failure of the testis to regress sufficiently in size to traverse the vaginal ring; overstretching of the gubernaculum; insufficient abdominal pressure to cause expansion of the vaginal process; inadequate growth of the gubernaculum and related structures, resulting in inadequate dilation of the vaginal ring and inguinal canal for the testis to pass through; and displacement of the testis into the pelvic cavity, where abdominal pressure prevents its passage through the inguinal canal.

Several reports suggest a genetic basis for cryptorchidism in horses. Some postulated methods of inheritance cryptorchidism in the horse include transmission by a simple autosomal recessive gene, transmission by an autosomal dominant gene, and transmission by at least two genetic factors, one of which is located on the sex chromosomes. All of the published studies dealing specifically with genetic aspects of cryptorchidism in horses suffer from the same weakness: the data presented are not adequate to support the models advocated for genetic transmission. Although cryptorchidism in many affected horses probably has a genetic basis, a definitive study dealing with a plausible genetic mechanism has yet to be performed; perhaps more than one pattern of inheritance exists. The effects of maternal environment and other factors, such as dystocia, on the development of cryptorchidism in horses have not been examined.

Retrospective studies of large numbers of cryptorchid horses indicate that retention of the right and left testis occurs nearly equally, but that unilateral retention occurs about nine times more often than does bilateral retention. Most (about 60%) retained right testes are located inguinally, whereas abdominal retention more commonly occurs with the left testis. Bilateral abdominal retention of testes is nearly 2.5 times more prevalent than bilateral inguinal retention. The occurrence of both abdominal and inguinal testes in the same horse is relatively uncommon.

Diagnosis of Cryptorchidism

Cryptorchidism is easily diagnosed if no attempt has been made to castrate the horse. External palpation of the scrotum reveals the absence of one or both testes. Gonadal agenesis is extremely rare, and so, if the history that the horse has not been castrated is reliable, the retained testis must be in an ectopic, inguinal, or abdominal position. Horses purchased as geldings but displaying stallion-like behavior pose more of a diagnostic challenge. One must determine whether the horse is cryptorchid and, if so, whether one or both testes are retained.

Palpation

Examination of a suspected cryptorchid begins with palpation of scrotal contents and the inguinal region. The scrotum should be inspected for scars, but a scrotal scar indicates only that an incision has been made, not that a testis has been removed. If both testes cannot be palpated, the horse should be administered a sedative and its genital area should be palpated again. Sedation may relax the cremaster muscles, thereby making a subcutaneous or inguinal testis more accessible. Because the average length of the inguinal canal is about 10 cm, testes high within the canal are difficult to palpate. An inguinal testis lies in the canal with its long axis in a vertical position. Because its epididymal tail precedes the testis during descent into the inguinal canal, the tail of the epididymis of a partial abdominal cryptorchid can be mistaken for a small, inguinal testis during palpation.

If external palpation fails to reveal both testes, the abdomen can be palpated per rectum to locate an abdominal testis. Male horses are at greater risk for rectal tear during palpation of the abdomen per rectum than are mares because male horses are seldom palpated per rectum and may resist more violently. Most cryptorchids are seen at a young age, and young horses are more prone to rectal tear because they have a smaller rectum and more nervous disposition and they strain more. Administration of caudal epidural anesthesia, the antispasmodic Buscopan (Boehringer Ingelheim, Ridgefield, Conn.), or sedation to the horse can facilitate palpation per rectum. The risks of injury to the rectum must be measured against the diagnostic value of the information to be gained from examination per rectum.

During palpation per rectum, the examiner attempts to trap the testis between the hand and abdominal wall just beyond the brim of the pelvis or to grasp the testis while sweeping the caudal area of the abdominal cavity. Actual palpation of an abdominal testis, however, is difficult because abdominal testes are small, flaccid, and often mobile. Locating the vaginal ring on the side of the suspected retained testis may be informative. The lateral aspect of the wrist should be positioned on the pubic brim near the pelvic symphysis. The fingertips are pressed against the abdominal wall, and the middle finger is flexed and extended in a cranioventral direction until it enters the slit-like vaginal ring (see Figure 13-18). If the area is palpated by flexing the fingers caudally, the medial border of the ring tends to close, causing the fingers to slide over the ring. Structures converging at the vaginal ring can sometimes be identified with palpation per rectum. The ductus deferens is the most readily palpable structure, and if the testis or epididymis has descended, it can usually be palpated as it exits the caudomedial aspect of the vaginal ring. The ipsilateral vaginal ring of a horse with complete abdominal retention of a testis is usually difficult to identify with palpation per rectum. If the vaginal ring can be identified, the testis, or at least the epididymis, has probably descended into the inguinal canal. A partial abdominal cryptorchid is difficult to differentiate from a horse whose epididymis and testis have both descended through the vaginal ring.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree