CHAPTER 16. Gastrointestinal Disorders

Michal Mazaki-Tovi

ORAL DISORDERS

I. Oronasal fistulas and palatal defects

A. Congenital defect in brachiocephalic breeds, miniature schnauzers, cocker spaniels, beagles, and cats

B. Acquired defect from trauma or maxillary periodontal pocket

C. Clinical signs include sneezing after eating and mucopurulent nasal discharge

D. Diagnosis is by physical examination

E. Surgery is treatment of choice

II. Stomatitis and gingivitis

A. Etiology includes periodontal disease, physical injury, chemical injury, systemic infections (herpesvirus, calicivirus in cats; Nocardia in dogs), oral candidiasis, necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis, immunosuppression secondary to feline leukemia virus (FeLV) or feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), uremia, plasma cell stomatitis (cats), feline eosinophilic granuloma complex, canine oral eosinophilic granuloma, autoimmune disorders, niacin deficiency, or oral neoplasia

B. Clinical signs include hypersalivation, halitosis, oral bleeding, dysphagia, anorexia, and weight loss

C. Diagnosis by history and physical examination primarily. Radiographs and laboratory tests may help to identify the underlying cause

D. Treatment

1. Treat the underlying cause

2. Symptomatic treatment includes dental prophylaxis, systemic antibiotics

III. Tonsillitis

A. Primary tonsillitis may occur in young, small-breed dogs, or tonsillitis may be secondary to chronic infections of the nasopharynx, vomiting, chronic regurgitation, or coughing

B. Clinical signs include retching, cough, fever, and anorexia

C. Diagnosis is based on physical examination and history

D. Treat with antibiotics, and treat the underlying disorder

IV. Tonsillar neoplasia

A. Squamous cell carcinoma and lymphoma are the most common causes

B. Clinical signs may include retching, coughing, and cervical mass (metastases to regional lymph nodes)

C. Diagnosis is based on oral examination and biopsy findings

D. Treat with chemotherapy

E. Prognosis is poor

V. Salivary gland diseases

A. Causes

1. Mucoceles (sialoceles) result from damage to the duct or gland and leakage of saliva into the tissues. Common sites include cervical and sublingual (ranulas) mucoceles

2. Fistulas are common and usually the result of trauma to the parotid salivary gland or duct

3. Sialoadenitis is uncommon and usually affects the zygomatic salivary gland

4. Sialoadenosis is a syndrome of unknown cause in dogs, characterized by mandibular salivary gland enlargement, associated with hypersalivation, retching, regurgitation, and vomiting. Response to phenobarbital is often excellent

5. Neoplasia of the salivary glands is rare

B. Clinical signs

1. Clinical signs of mucoceles depend on the gland affected. Cervical mucoceles present as soft nonpainful masses; ranulas cause dysphagia and blood-tinged saliva; pharyngeal mucocele may cause breathing or swallowing difficulty; and zygomatic mucoceles may cause exophthalmos

2. Fistulas present as a small skin opening draining serous fluid

3. Zygomatic sialoadenitis causes exophthalmos, pain on opening the mouth, and mucopurulent discharge from the duct. Parotid sialoadenitis presents as a painful, warm parotid gland and discharge

4. Sialoadenosis is usually associated with chronic signs, including hypersalivation, retching, regurgitation, and vomiting

5. Neoplasia usually presents as a nonpainful mass in the region of the salivary gland

C. Diagnosis

1. The diagnosis of mucoceles is usually based on palpation and aspiration of viscid, mucinous fluid that is consistent with saliva

2. Sialography may be used to diagnose fistulas but is usually not necessary

3. Sialoadenitis is diagnosed based on complete blood cell count (CBC) and histopathology findings

D. Treatment

1. Cervical mucoceles are treated by surgical excision of the mandibular and sublingual salivary glands (for cervical and pharyngeal mucoceles) or zygomatic salivary gland (for zygomatic mucocele). Ranulas may be treated by surgical marsupialization

2. Sialoadenitis: Treat with systemic antibiotics, drainage of the abscess, and application of warm compresses

3. Sialoadenosis: Treat with long-term therapy (phenobarbital or potassium bromide) is usually required

4. Neoplasia: Treat with surgical removal. Postoperative chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or both may be beneficial for adenocarcinoma

ESOPHAGUS AND DISORDERS OF SWALLOWING

I. Overview

A. Cause is either a structural disorder or a motility disorder

B. Clinical signs include regurgitation, dysphagia, odynophagia, ptyalism, exaggerated swallowing, weight loss, polyphagia, anorexia, cough, dyspnea, and fever

C. Diagnosis is based on history and a careful physical examination to detect alterations of swallowing. Imaging is most important for the diagnosis. Endoscopy can also be used. Consider Spirocerca lupi infection in the southern United States

D. Treatment includes specific therapy for the underlying condition, along with general symptomatic management

II. Oropharyngeal dysphagia

A. Causes

1. Oral dysphagia involves difficulty with prehension or transport of food to the pharynx

2. Pharyngeal dysphagia involves problems with transport of a bolus from the oropharynx through the cranial esophageal sphincter and includes cricopharyngeal achalasia and cricopharyngeal asynchrony

3. Caused by morphologic (e.g., foreign body, dental disease, oral neoplasia, stomatitis, retropharyngeal abscess, cleft palate, etc.) or functional (e.g., neuromuscular) disorders

B. Clinical signs

1. Oral dysphagia is characterized by abnormal prehension and mastication

2. Pharyngeal dysphagia is characterized by repeated unsuccessful attempt to swallow with gagging, retching, and spitting of food. Aspiration pneumonia is common

3. Regurgitation may occur with concurrent megaesophagus and generalized muscle weakness, or neurologic deficits may occur when there is an underlying neuromuscular disorder

C. Diagnosis

1. Signalment may suggest breed dispositions for congenital neuromuscular disorders (e.g., hereditary muscular dystrophy in Bouvier)

2. Morphologic diseases can be detected by visual examination of the oropharynx, and generalized neuromuscular abnormalities may be detected by complete physical and neurologic examination

3. Imaging

a. Radiographs of the oropharyngeal area may identify morphologic disorders (e.g., foreign body)

b. Thoracic radiographs may reveal aspiration pneumonia or concurrent megaesophagus

c. Fluoroscopy with a barium swallow is required for the diagnosis of functional abnormalities

d. Ancillary testing is usually required for the diagnosis of generalized neuromuscular disorders

D. Treatment and prognosis depend on the underlying disorder. Administer supportive treatment as needed

III. Esophageal hypomotility

A. Causes

1. May be segmental or diffuse (megaesophagus); congenital or acquired

2. Megaesophagus is idiopathic in most dogs

3. Acquired megaesophagus may occur secondary to diseases causing diffuse neuromuscular dysfunction (e.g., myasthenia gravis, dysautonomia, polyneuropathy, polymyositis, botulism, tick paralysis, anticholinesterase, lead, or thallium toxicity, hypothyroidism, hypoadrenocorticism), esophagitis, or hiatal hernia (common in cats)

B. Regurgitation is the primary clinical sign and may not be related to eating. Dyspnea, cough, and fever suggest aspiration pneumonia. Signs of an underlying disorder may be present

C. Diagnosis: Idiopathic megaesophagus is a diagnosis of exclusion

1. Signalment and history

a. Breeds predisposed for idiopathic megaesophagus include German shepherd dog, Great Dane, greyhound, golden retriever, Labrador retriever, Irish setter, miniature schnauzer, Newfoundland, shar-pei, wirehaired fox terrier, and Siamese cat

b. Congenital disorders are suggested when signs are first noted at the time of weaning

c. History of chronic or recurrent respiratory infections may indicate secondary aspiration pneumonia

2. Physical examination

a. May be unremarkable except for weight loss. Distension of the cervical esophagus may become evident by compressing the thorax while the nostrils are closed

b. Nasal discharge and additional signs associated with underlying disorders may be present

3. Imaging

a. Survey and contrast thoracic radiography may suggest megaesophagus and aspiration pneumonia (as described above)

b. Barium swallow fluoroscopy can detect esophageal motility disorders

4. Routine laboratory tests

a. A CBC may reveal neutrophilia and a left shift with aspiration pneumonia

b. Biochemical profile may reveal abnormalities associated with underlying disorders

c. Acetylcholine receptor antibody titer to evaluate for acquired myasthenia gravis is indicated even in the absence of generalized signs, as myasthenia gravis may be focal

5. Ancillary tests to evaluate for underlying causes as indicated

6. Esophagoscopy is indicated when an obstructive disease or reflux esophagitis is suspected

D. Treatment is symptomatic and supportive in most cases

1. Feed frequent small meals with the animal in an upright position. Liquid food is better tolerated in most cases, but different food types should be tried to identify the best option. Gastrostomy tube may be required in some cases

2. Administer antibiotic therapy for aspiration pneumonia

E. Idiopathic Megaesophagus is usually irreversible and supportive care is required for life

IV. Esophageal foreign body

A. Foreign bodies commonly found in dogs are bones and in cats vomited hairballs. These usually lodge at the thoracic inlet, base of the heart, or hiatus of the diaphragm. Complications include esophagitis, esophageal perforation and mediastinitis, esophageal stricture, and bronchoesophageal fistula

B. Clinical signs include acute onset of gagging, salivation, dysphagia, and regurgitation. Depression, fever, cough, and dyspnea may suggest aspiration pneumonia

C. Diagnosis is usually confirmed with radiography, barium contrast esophageal radiography, or esophagoscopy. Bones or metal foreign bodies are usually apparent on survey thoracic and cervical radiographs. Evaluate thoracic radiographs for aspiration pneumonia. Findings of pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, and mediastinal or pleural effusion suggest esophageal perforation

D. Endoscopic removal is preferred in most cases

1. If the object cannot be extracted orally, advance it to the stomach to be removed by gastrostomy (bones may dissolve). Withhold food and water for 24 hours after the procedure. Administer antibiotics if indicated

2. An esophagotomy is indicated if the foreign body cannot be retrieved orally or advanced into the stomach

E. Prognosis is excellent unless perforation or aspiration pneumonia is present

V. Esophageal perforation

A. Foreign bodies are the most common cause; penetrating wounds are also common. Iatrogenic perforation may occur during esophagoscopy

B. Clinical signs include anorexia, depression, odynophagia, and a rigid stance. Cervical swelling, cellulitis, or a draining fistula may be present with cervical esophageal perforation. Cough, dyspnea, and fever may occur with mediastinitis or pleuritis

C. Thoracic radiography may show pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, and mediastinal or pleural effusion. The CBC usually reveals neutrophilia with a left shift

D. Surgical repair is needed if the perforation is large, or mediastinitis or pleuritis occur

E. Medical management is sufficient for small tears. Give parenteral antibiotics, fluid therapy, and nothing per os for 5 to 7 days. Consider feeding by gastrostomy tube or parenteral nutritional support

VI. Esophagitis

A. Causes of esophagitis include foreign bodies, oral medications (doxycycline), thermal injury, caustic injury, Pythium insidiosum infection, and gastroesophageal reflux associated with chronic vomiting, hiatal hernia, general anesthesia, or indwelling nasogastric (NG) tube

B. Clinical signs are nonspecific for esophageal disease and may be absent with mild esophagitis

C. Esophagoscopy is the most sensitive method of diagnosis

1. Findings include mucosal erythema, hemorrhage, erosions, ulcers, strictures (in severe cases)

2. With gastroesophageal reflux, lesions are most severe in the distal esophagus, the gastroesophageal junction may appear dilated, and reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus may be noted

D. Treatment

1. General therapy involves antibiotic therapy and frequent feeding of small portions of soft food

2. For reflux esophagitis, give promotility agents (metoclopramide), histamine type 2 (H 2)-receptor blockers, sucralfate, and prednisolone

E. Prognosis is good for mild to moderate esophagitis and guarded or poor for severe esophagitis

VII. Esophageal stricture

A. Strictures may be the result of severe esophagitis or esophageal surgery

B. Regurgitation usually occurs immediately after eating, but it might not be related to eating in chronic cases

C. If due to injury, signs of stricture usually occur within 14 days

D. Radiography may show distention of the esophagus proximal to the stricture. Contrast studies or endoscopy may be helpful in the diagnosis

E. Treatment is usually by balloon catheter dilatation. Prednisolone helps prevent further fibrosis and stricture

VIII. Esophageal diverticula

A. Diverticula are pouchlike sacculations of the esophageal wall and may be congenital or acquired. Diverticula may become impacted, leading to esophagitis

B. Clinical signs include regurgitation, distress after eating, intermittent thoracic pain, and respiratory distress

C. Thoracic radiography may reveal a gas- or food-filled mass in the area of the esophagus. Barium esophagram or esophagoscopy may confirm the diagnosis

D. Large diverticula require surgical resection, but small diverticula can be managed by feeding frequent small meals of soft food with the animal in an upright position

IX. Esophageal fistula

A. Fistulas are communications between the esophagus and airways, most commonly the bronchi. Acquired fistulas are more common than congenital fistulas and may be caused by esophageal foreign body, trauma, malignancy, or infection. Bronchoesophageal fistulas are frequently associated with esophageal diverticula

B. Clinical signs are related to contamination of the airways with fluid and food. Coughing, fever, and dyspnea are common

C. Diagnosis is based on physical examination findings, thoracic radiography, and confirmation with a barium esophagram

D. Treatment is surgical resection of the fistula with appropriate antibiotic therapy

E. Prognosis is poor if complications (e.g., pulmonary abscess, pleuritis) are present

X. Vascular ring anomalies

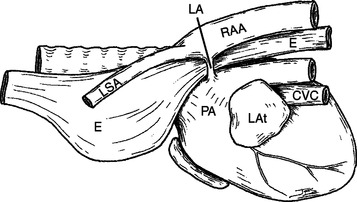

A. Causes (Figure 16-1)

|

| Figure 16-1 Schematic of persistent right aortic arch. This view, from the left, shows the ligamentum arteriosum (LA) connecting the descending right aortic arch (RAA) to the main or left pulmonary artery (PA) causing constriction of the esophagus (E) between these structures and the heart base. CVC, Caudal vena cava; LAt, left atrium; LSA, left subclavian artery. (From Thrall DE. Textbook of Veterinary Diagnostic Radiology, 5th ed. St Louis, 2007, Saunders.) |

1. Persistent right aortic arch (PRAA) accounts for 95% of vascular ring anomalies in dogs and cats. The right rather than the left fourth aortic arch is retained, resulting in compression of the esophagus between the ligamentum arteriosum, the aorta, the pulmonary trunk, and base of the heart

2. There is a familial tendency in some breeds (e.g., German shepherd dog, Irish setter)

B. Clinical signs include regurgitation that begins at the time of weaning, failure to gain weight, and cough and dyspnea (with aspiration pneumonia)

C. Survey thoracic radiography findings suggesting PRAA include esophageal dilatation cranial to the heart, absence of the normal bulge of the aortic arch, and leftward tracheal deviation cranial to the heart. Barium esophagram may confirm the location of the esophageal obstruction

D. Treatment involves surgical ligation and antibiotic therapy if indicated. Prognosis for recovery of esophageal function is better if the surgery is performed early

XI. Hiatal disorders

A. Causes

1. Hiatal hernias: A sliding hiatal hernia is a protrusion of the distal esophagus and stomach through an enlarged esophageal hiatus into the thorax. A congenital form has been described in shar-peis. It may also occur secondary to high positive intraabdominal pressure (e.g., abdominal trauma, vomiting), chronic upper airway obstruction (e.g., brachycephalic syndrome), or tetanus

2. Gastroesophageal intussusception, an invagination of the stomach into the distal esophagus, is seen with congenital idiopathic megaesophagus

B. Clinical signs of small hiatal hernias are due primarily to reflux esophagitis (regurgitation, hypersalivation). When large portions of the stomach are displaced, signs of gastric and esophageal obstruction occur and may include dyspnea, hematemesis, collapse, rapid deterioration, and death

C. Radiography, barium esophagram, or endoscopy may confirm the diagnosis

D. Surgery is indicated for the treatment of large hernias. Small hernias may be managed medically with treatment for reflux esophagitis and frequent feeding of small portions of low-fat soft-food diet

XII. Periesophageal obstruction

A. Extraluminal compression can be caused by cervical or mediastinal masses

B. Clinical signs include chronic progressive regurgitation, dysphagia, and hypersalivation in addition to other signs related to neoplasia

C. Thoracic radiography usually reveals an intrathoracic mass

D. Treat the underlying cause

XIII. Esophageal neoplasia

A. Primary neoplasia is rare. Leiomyoma is the most common neoplasia in dogs, and squamous cell carcinoma is most common in cats. Osteosarcoma and fibrosarcoma in dogs may develop with malignant transformation of a granuloma caused by Spirocerca lupi. Other tumors occasionally metastasize to the esophagus

B. Clinical signs include regurgitation, dysphagia, and ptyalism

D. Surgical excision is required

STOMACH DISORDERS

I. Vomiting

A. A common clinical sign associated with gastrointestinal (GI) and non-GI disorders

1. Frequently is preceded by nausea (hypersalivation, repeated licking and swallowing), retching, and abdominal contractions

2. Vomitus consists of stomach and duodenal contents (food, mucus, and foamy or bile-stained fluid with a neutral or acidic pH) and may contain blood (hematemesis)

3. Projectile vomiting usually indicates gastric outlet or upper small bowel obstruction

4. Vomiting of undigested food more than 12 hours after eating suggests delayed gastric emptying

B. Diagnosis

1. Careful review of history and physical examination is required. Include oral and rectal examinations, abdominal palpation, review of vaccination and deworming history

2. Laboratory evaluation includes routine hematology, biochemistry, urinalysis, and additional tests as indicated. Fecal flotation tests may be indicated

3. Imaging

a. Routine abdominal radiographs may identify radiopaque foreign bodies, GI obstruction, or mural thickening. Barium contrast may additionally identify radiolucent foreign bodies. Barium mixed with food and barium-impregnated plastic spheres (BIPS) may detect gastric retention disorders. Use aqueous iodide contrast if perforation is suspected

b. Abdominal ultrasonography is useful to evaluate non-GI causes of vomiting (e.g., pancreatitis, hepatic, or renal disease) and GI disorders (e.g., intussusception, or masses)

4. Endoscopy or exploratory laparotomy may be necessary

C. Symptomatic and supportive treatment

1. Fluid therapy. Intravenous therapy is preferred.

2. Withhold food for 12 to 24 hours, then offer a highly digestible diet (chicken and rice) for 2 to 3 days. Gradually reintroduce the routine diet over 2 to 3 days

3. Antiemetics. Phenothiazines are widely used but may decrease seizure threshold. Metoclopramide should not be used in animals with seizures. Butorphanol is also commonly used. Avoid anticholinergic drugs

II. Acute gastritis

A. Common, usually mild and self-limiting. Possible causes include dietary indiscretion, foreign body causing mechanical irritation, chemical irritants, and drugs

B. Clinical signs include acute onset of nausea and vomiting

C. Diagnosis is supported by response to therapy in 1 to 2 days

D. Treat the underlying cause, withhold food for 12 to 24 hours, then offer a bland diet. Correct dehydration if present; consider antiemetic and acid control therapy

III. Gastric foreign bodies

A. Gastric foreign bodies are most common in dogs. Linear foreign bodies are more likely in cats

B. The most common clinical sign is acute-onset vomiting, but some may present with chronic vomiting. Additional signs may relate to the foreign body ingested (zinc or lead toxicity)

C. Gastric foreign body should be considered in all animals with acute vomiting. Radiography may identify the object and reveal a distended stomach

D. Endoscopic removal is preferred. Asymptomatic animals may be managed conservatively. Perform gastrostomy if object cannot be removed via endoscopy

IV. Gastroduodenal ulceration and bleeding

A. Causes include nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, chronic gastritis, hepatic disease, renal failure, neurologic disease, hypoadrenocorticism, gastric neoplasia, mast cell tumors, gastrinoma, or stress

B. Clinical signs include anorexia, vomiting, hematemesis, melena, abdominal pain, and weight loss. Acute onset abdominal pain, depression, and collapse suggest ulcer perforation and septic shock

C. Diagnosis

1. Carefully review drug history for administration of ulcerogenic drugs

2. Laboratory evaluation may show regenerative anemia or microcytic hypochromic anemia with chronic blood loss. Evaluate for underlying disorders

3. Radiographs or GI contrast studies may be useful

4. Abdominocentesis is indicated if perforation is suspected

5. Endoscopy or laparotomy may be useful

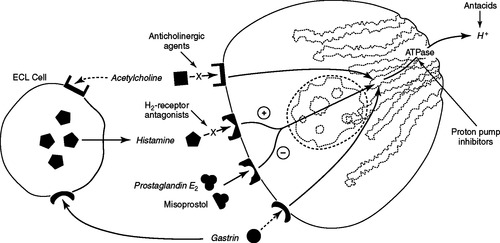

D. Treat with H 2 blockers to control gastric acid secretion, and sucralfate for mucosal protection. Give antibiotics or other supportive therapy as needed (Figure 16-2)

|

| Figure 16-2 Representation of a gastric parietal cell showing the site of action of various therapeutic agents used to decrease gastric acid secretion. Histamine type 2 (H 2) antagonists (blockers) competitively inhibit acid secretion stimulated by histamine, which is released from nearby enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells by gastrin stimulation. Acetylcholine also indirectly stimulates histamine release from the ECL cells. Use of anticholinergic drugs to inhibit acid secretion is limited by systemic side effects. Prostaglandin (PGE 2) analogues, such as misoprostol, inhibit acid secretion by blocking histamine-induced cyclic adenosine monophosphate production. Proton pump inhibitors such as omeprazole and pantoprazole have broad-spectrum antisecretory activity because they interrupt the final common pathway of acid secretion by inhibiting hydrogen potassium adenosine triphosphatase. Antacids neutralize luminal gastric acid. (From Birchard SJ, Sherding RG. Saunders Manual of Small Animal Clinical Practice, 3rd ed. St Louis, 2006, Saunders.) |

V. Chronic Gastritis

A. Lymphocytic-plasmacytic gastritis is a common histologic diagnosis

1. Etiology

a. Idiopathic chronic gastritis is usually attributed to dietary allergy or intolerance, occult parasitism, or a reaction to bacterial antigens, or unknown pathogens

b. Specific causes include infection with Physaloptera rara, Ollulanus tricuspis (cats), Pythium insidiosum (dogs), or Helicobacter, enterogastric reflux, or chronic mucosal irritation

3. Endoscopy is the diagnostic method of choice. Mucosal abnormalities include irregularity, firmness, or ulceration. Laparotomy may be indicated for biopsies

B. Eosinophilic gastritis and granuloma

1. Eosinophilic infiltration is usually diffuse but may present as a granulomatous lesion in dogs. An allergic or immunologic hypersensitivity has been suggested. Eosinophilic gastritis is rarely associated with hypereosinophilic syndrome in cats

2. Clinical signs include chronic vomiting, hematemesis, melena, anorexia, and weight loss

3. Endoscopy is the diagnostic method of choice. Laparotomy may be indicated to obtain gastric biopsies

C. Therapy for chronic gastritis

1. Treat any underlying disorder

2. Dietary trial with an easily digestible, moderately fat-restricted, carbohydrate-based diet, with a novel protein source. Feed frequent small meals, and assess response after 3 to 4 weeks

3. H 2 blockers may be useful. Promotility drugs may be indicated

4. Prednisolone or azathioprine may be used if there is no response to dietary trial or H 2 blockers

5. Antibacterial therapy is used for Helicobacter infection

6. Surgery may be indicated to correct gastric outflow obstruction

D. The prognosis is good when the underlying cause is identified. Long-term management is usually required

VI. Gastric outflow obstruction

A. Causes include foreign bodies, chronic hypertrophic pyloric gastropathy, congenital pyloric stenosis, pyloric mass, gastric dilatation-volvulus, or extrinsic compression

B. Clinical signs include projectile vomiting of undigested food, abdominal distention, belching, and weight loss

C. Diagnosis

1. Laboratory findings are unremarkable unless profuse vomiting occurs and results in hypokalemia, hyponatremia, hypochloremia, and metabolic alkalosis

2. The finding of a distended stomach filled with food more than 12 hours after eating suggests delayed gastric emptying. Endoscopy may be useful to identify foreign bodies and masses

D. Surgery is the definitive therapy. Administer fluid therapy and gastric promotility drugs if necessary

VII. Gastric motility disorders

A. Possible factors include drugs (e.g., anticholinergic, adrenergic, or narcotic), gastric or abdominal inflammation, metabolic abnormalities (e.g., hypokalemia, endotoxemia, hypothyroidism), neurogenic causes (e.g., dysautonomia), nervous inhibition (stress, pain), or prolonged mechanical obstruction

C. Abdominal radiograph may suggest delayed gastric emptying as described for gastric outflow obstruction. However, the gastric outflow region appears normal

D. Treat the underlying cause. Feed a diet low in fat and high in digestible carbohydrate. Feed small amounts frequently. A liquid diet may be better tolerated. Use promotility drugs as needed

VIII. Hypertrophic gastropathy is a heterogeneous group of disorders

A. Cause is unknown in most cases. Possible causes include stress in excitable small-breed dogs, chronic irritation from aspirin therapy, or hypergastrinemia

B. Clinical signs include chronic intermittent vomiting, anorexia, weight loss, abdominal distension, hematemesis, and concurrent diarrhea in basenjis. Typically occurs in small-breed dogs with chronic intermittent vomiting

C. Metabolic alkalosis may occur with profuse vomiting and gastric outflow obstruction. Gastrin concentrations may be elevated. Radiography shows delayed gastric emptying. Surgery is required to obtain a full-thickness biopsy

D. Surgical excision may be necessary to relieve outflow obstruction. Promotility drugs may be needed after surgery. Treatment may also include H 2 blockers, sucralfate, or prednisolone if indicated

IX. Gastric neoplasia

A. Adenocarcinoma is most common in dogs, and lymphoma is most common in cats. Leiomyosarcoma and fibrosarcoma are less common

B. Leiomyomas are the second most common gastric tumors in dogs. Benign adenomatous polyps occur infrequently in dogs and cats

C. Clinical signs include progressive vomiting, hematemesis, anorexia, and weight loss. Clinical signs may be absent with benign tumors unless obstruction occurs

D. Contrast radiography and endoscopy are most useful for diagnosis

E. Removal by partial gastrectomy is the treatment of choice, with chemotherapy if indicated. Prognosis is good for benign tumors but poor for adenocarcinoma

X. Gastric dilatation-volvulus (GDV)

A. GDV causes complete obstruction of gastric outflow, which impairs venous return through the vena cava causing hypovolemic and endotoxic shock

B. The cause is unknown. Older large-breed, deep-chested dogs are predisposed. Risk factors include having a first-degree relative affected by GDV, lean body conformation, rapid eating, eating from a raised bowl, eating one meal daily, exercise or stress after a meal, and a fearful temperament

C. Clinical signs include acute onset of abdominal distension, nonproductive retching, salivating, and respiratory distress

D. Physical examination usually reveals tympani on abdominal percussion and findings indicative of hypovolemia or shock. Hypokalemia and metabolic acidosis are often present. Radiography shows overdistension of the stomach with gas, pyloric displacement, and compartmentalization of the stomach on lateral view. Splenomegaly is also seen. Pneumoperitoneum suggests gastric perforation

E. Initial medical management

1. Decompress the stomach, preferably by intubation

2. Administer fluids and treat for shock

3. Control infection and endotoxemia with antibiotics and glucocorticoids

4. Treat cardiac arrhythmias; correct hypokalemia

F. Surgical management is aimed at repositioning of the stomach and spleen, resecting devitalized gastric and splenic tissue, and permanently fixing the stomach to prevent future recurrences of volvulus

G. Prevention involves feeding frequent, small portions of food, and restricting exercise and access to water for 1 hour after eating

XI. Surgery of the stomach. See Chapter 27 for a review of surgical procedures

INTESTINAL DISORDERS

I. Diarrhea overview

A. Acute vs. chronic diarrhea

1. Acute diarrhea has a sudden onset, with duration of 3 weeks or less. Treatment is mainly supportive and nonspecific

2. Chronic diarrhea persists for 4 weeks or longer or has episodic recurrence

B. Small bowel vs. large bowel

1. Small bowel diarrhea is characterized by a large volume of feces with a rancid smell. May be associated with excessive flatulence and weight loss. Steatorrhea may occur in maldigestive or malabsorptive disorders

2. Large bowel diarrhea is characterized by frequent urges to defecate, straining, and small quantities of feces. Hematochezia, mucus, or exudates may be present

C. Diagnostic approach for diarrhea (Table 16-1)

| Physical Finding | Potential Clinical Associations |

|---|---|

| General Physical Examination | |

| Dehydration | Diarrheal fluid loss |

| Depression or weakness | Electrolyte imbalance, severe debilitation |

| Emaciation or malnutrition | Chronic malabsorption, protein-losing enteropathy |

| Dull unthrifty hair coat | Malabsorption of fatty acids, protein, and vitamins |

| Fever | Infection, transmural inflammation, neoplasia |

| Edema, ascites, pleural effusion | Protein-losing enteropathy |

| Pallor (anemia) | Gastrointestinal blood loss, anemia of chronic inflammation |

| Intestinal Palpation | |

| Masses | Foreign body, neoplasia, granuloma |

| Thickened loops | Infiltration (inflammation, lymphoma) |

| “Sausage loop” | Intussusception |

| Aggregated loops | Linear intestinal foreign body, peritoneal adhesions |

| Pain | Inflammation, obstruction, ischemia, peritonitis |

| Gas of fluid distention | Obstruction, ileus, diarrhea |

| Mesenteric lymphadenopathy | Inflammation, infection, neoplasia |

| Rectal Palpation | |

| Masses | Polyp, granuloma, neoplasia |

| Circumferential narrowing | Stricture, spasm, neoplasia |

| Coarse mucosal texture | Colitis, neoplasia |

1. History: Consider extraintestinal causes of diarrhea. Review the mode of onset; duration; clinical course; fecal characteristics; correlation with diet, medication, or stressful events; response to treatment; and association with other signs

2. Physical examination: Perform rectal examination, and palpate abdomen. Look for signs of systemic disease

3. Routine laboratory tests (CBC, biochemistry profile) and thyroid profile in cats to exclude hyperthyroidism

4. Fecal examination for parasites, bacteria, blood, and fecal fat

5. Serum folate and cobalamin assays. Serum folate may be decreased in enteropathies that impair absorption in the proximal small intestine, and increased with overproliferation of the normal intestinal flora, or exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI). Serum cobalamin may be decreased in EPI, enteropathies that impair absorption in the distal small intestine, or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth

6. Imaging, including plain radiography, barium radiography, or ultrasonography

7. Endoscopy or laparotomy

D. Nonspecific treatment of diarrhea

1. Dietary management

a. Acute diarrhea: Restrict food intake for at least 24 hours and then give bland, low-fat foods (e.g., boiled rice and chicken or low-fat cottage cheese) in small amounts at frequent intervals. Gradually reintroduce the animal’s regular diet when the diarrhea has been resolved for 48 hours

b. Chronic diarrhea: Give three or four meals a day, and use appropriate diets (fiber-supplemented if large bowel diarrhea; novel protein diets with inflammatory bowel disease [IBD]).

2. Fluid therapy to correct dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities

3. Antidiarrheal drugs are used short-term to control fluid loss. Loperamide or diphenoxylate are most effective

4. Corticosteroids are indicated for IBD, and NSAIDs may be used in chronic colitis

5. Antibiotic should be used only to treat specific bacterial enteropathogens

6. Fenbendazole therapy for common intestinal nematodes and Giardia spp.

7. Cobalamin therapy in chronic small intestinal disease or exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

II. Dietary diarrhea

A. Dietary indiscretions include overeating, ingestion of spoiled garbage, and ingestion of abrasive or indigestible foreign material that can traumatize the GI mucosa. Common in dogs

B. Diagnosis is by review of history

C. Self-limiting with feeding of a restricted diet and prevention of indiscriminant eating

III. Drug- and toxin-induced diarrhea

A. Many medications may cause diarrhea (e.g. NSAIDs, digitalis, lactulose, antihelmintics, antibiotics, many antineoplastic drugs). Dexamethasone has been associated with hemorrhagic gastroenterocolitis, especially in dogs with intervertebral disc disease

B. Many exogenous toxins cause diarrhea (e.g., bacterial enterotoxins causing food poisoning, heavy metals, insecticides)

C. Diagnosis is based on a review of the history

D. Diarrhea usually resolves with discontinuation of the medication or dose reduction, and with elimination of the toxin from the body. Give supportive treatment as indicated

IV. Intestinal parasites: Helminths

A. Ascarids

1. Toxocara canis is the most prevalent intestinal parasites of dogs. Toxocara cati occurs in cats

2. Routes of infection include transplacental ( T. canis), milk-borne ( T. canis, T. cati), ingestion of infective eggs (all), ingestion of a paratenic host ( T. canis), or an intermediate host ( T. leonina)

3. Clinical signs occur most often in puppies and kittens and may include abdominal discomfort, potbelly, stunted growth, and diarrhea. Intestinal obstruction caused by large masses of worms or severe lung damage due to migration occurs rarely

4. Diagnose on routine fecal examination

5. Treat with pyrantel pamoate

6. Toxocaral visceral larval migrans can occur in humans when larva penetrate the skin

B. Hookworms

1. Ancylostoma caninum, the most common hookworm in the dog, is a bloodsucker. Ancylostoma tubaeforme, the common hookworm in the cat, feeds on tissue. Ancylostoma braziliense (southern United States) and Uncinaria stenocephala (Canada) are less common in dogs and cats and are only mildly pathogenic

3. Clinical signs are associated mostly with blood-sucking activity and include melena, bloody diarrhea, pallor, emaciation, and dehydration. Acute blood loss in neonates may lead to death. Chronic blood loss in older animals results in iron deficiency anemia

4. Diagnose on routine fecal flotation

5. Treat with pyrantel pamoate (safest for pups), fenbendazole, or febantel

C. Whipworms

1. Trichuris vulpis is common in dogs. The adult nematode attaches to the colonic and cecal mucosa, where it feeds on blood and tissue fluids, thereby causing colitis and typhlitis

2. Infection occurs by ingestion of infective ova, and the life cycle is direct. Ova may remain infectious in the environment for 4 to 5 years

3. Acute, chronic, or intermittent signs of large bowel–type diarrhea occur commonly. Hematochezia may sometimes occur

4. Ova can be identified on fecal flotation. Hyperkalemia and hyponatremia may occur with severe diarrhea

5. Treat with fenbendazole or febantel. Retreat every 2 to 3 months if dogs have access to contaminated ground

D. Strongyloides

1. Found in the southern Gulf States. Strongyloides stercoralis resides in the proximal small intestines in dogs. Strongyloides tumefaciens resides in the large intestines in cats

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree