CHAPTER 13. Examination of the Stallion for Breeding Soundness

OBJECTIVES

While studying the information covered in this chapter, the reader should attempt to:

■ Acquire a working understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the reproductive organs of the stallion.

■ Acquire a working understanding of how abnormalities of the reproductive organs, conditions associated with suboptimal general physical soundness, or disordered sexual behavior can adversely affect stallion fertility.

■ Acquire a working understanding of procedures used for evaluation of a stallion for breeding soundness.

STUDY QUESTIONS

1. Describe the objective of a breeding soundness examination of a stallion.

2. List procedures that should be performed during a breeding soundness examination of a stallion.

3. Describe the anatomy of the normal reproductive tract of a stallion, including the prepuce, penis, scrotum and its contents, vas deferens, and accessory sex glands.

4. List potential venereal pathogens that may be transmitted by stallions.

5. Describe procedures used for evaluation of semen quality of stallions, including but not limited to:

a. Gross evaluation of semen

b. Sperm concentration

c. Semen volume

d. Number of sperm in ejaculate

e. Semen pH

f. Sperm motility

g. Sperm morphology

6. Summarize minimal criteria for classification of a stallion as a satisfactory breeding prospect.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of a breeding soundness examination is to determine whether a stallion has the mental and physical faculties necessary to deliver semen that contains viable sperm but no infectious disease to the mare’s reproductive tract at the proper time, ensuring the establishment of pregnancy in a reasonable number of mares bred per season. The examiner not only evaluates the quality and quantity of ejaculated sperm but also tests the libido and mating ability of a stallion, attempts to recognize congenital defects that may be transmissible to offspring or decrease a stallion’s fertility, identifies infectious diseases that may be transmitted venereally, and searches for any other lesions that may reduce a stallion’s longevity as a sire.

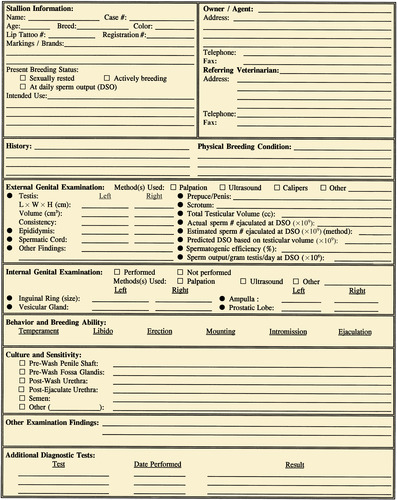

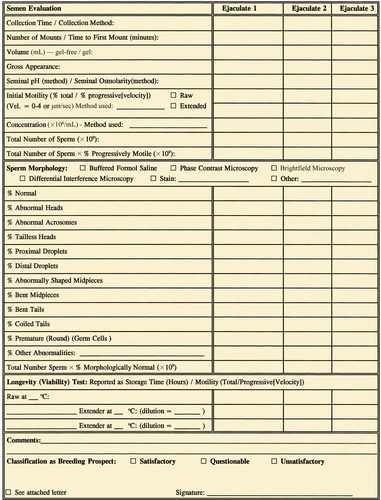

A record that summarizes results of the breeding soundness examination should be provided to the owner of the stallion after completion of the examination. An example of a form used for this purpose is shown in Figure 13-1.

HISTORY AND IDENTIFICATION

Collection of historical information about a stallion is an indispensable part of a breeding soundness examination. This information should be gathered in a methodical unassuming manner to ensure completeness and avoid inaccuracies. Possible environmental and heritable causes for the presenting problem should be addressed, and previous modes of therapy for an existing problem should be investigated when applicable. A historical review of stallions to be examined for breeding soundness should include their present usage, previous breeding performance, results of prior fertility evaluations, illnesses, injuries, and medications and vaccinations, with explicit information about previous and current reproductive management and medical programs.

Positive identification of the stallion, often considered a mundane procedure, is an integral part of the examination process, especially when sale of the horse is involved. Identification of a stallion must be accurate to avoid any ambiguity in identity at a subsequent date. Name, age, breed, and registration number of the stallion are recorded, in addition to identifying marks, such as lip tattoos, hide brands, color markings, and hair whorls. When possible, photographs of the stallion should be taken for permanent identification.

GENERAL PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Although a breeding soundness examination focuses on the genital health of stallions, general physical condition cannot be ignored. An assessment of general body condition is done first. Particular attention should be given to abnormalities that affect mating ability (e.g., lameness, back pain, ataxia) or that are potentially heritable (e.g., cryptorchidism, parrot mouth, wobbler syndrome). All abnormalities are recorded. Examination of the various body systems (respiratory, cardiovascular, digestive, nervous, urinary, ophthalmic, and musculoskeletal) can be cursory, although abnormalities should be noted and pursued further diagnostically if the potential exists for interference with breeding ability or fertility. Common laboratory tests (Coggins test, hematologic analysis, serum chemistry, urinalysis, and fecal egg counts) can support physical examination findings in determination of the general health of a stallion.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION OF REPRODUCTIVE TRACT

Knowledge of normal genital anatomy is essential to a competent physical examination of the stallion’s reproductive tract. A thorough physical examination of both external and internal genital organs always should be incorporated into procedures for prediction of stallion fertility.

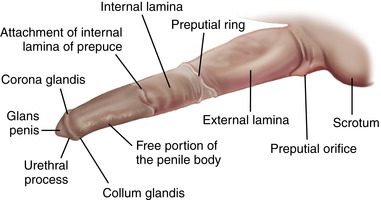

External Genitalia

The preferred method to allow close inspection of the penis (Figure 13-2 and Figure 13-3) is to stimulate penile tumescence through exposure of the stallion to a mare in estrus. This procedure also permits assessment of sexual behavior, including erection capability. Manual extraction of the penis from the prepuce for examination is difficult and usually met with resistance from the stallion. In shy stallions, the penis can often be visualized from a distance while the horse urinates. Urination can sometimes be stimulated by placing the horse in a freshly bedded stall; shaking the bedding may increase the horse’s urge to urinate. Tranquilization (acepromazine or xylazine) elicits penile prolapse, making the penis accessible; however, tranquilizers, especially those that are phenothiazine-derived (e.g., acepromazine), can cause penile paralysis or priapism and therefore should not be used indiscriminately. In addition, tranquilizers will probably render the horse ataxic which may interfere with mounting when collection of semen is attempted.

|

| Figure 13-2 |

|

| Figure 13-3 |

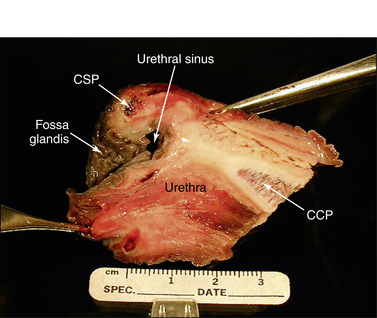

The penis may need cleansing before its inspection (Figure 13-4) because epithelial debris mixed with secretions from the preputial glands accumulates in the preputial cavity and on the exterior of the penis when it is unattended. The root and proximal body of the penis are buried in tissue, thereby limiting the examination to the exposed body and glans. The penis should be examined thoroughly, and any palpable or visual lesions should be recorded. Particular attention should be given to the fossa glandis and urethral process because they are partially concealed and smegma accumulates in these areas (Figure 13-5, Figure 13-6 and Figure 13-7). Common penile lesions include those of traumatic origin and vesicles or pustules of equine coital exanthema, Habronema granulomas, squamous cell carcinomas, and papillomas (see Chapter 16).

|

| Figure 13-7 (Courtesy Dr. Donald Schlafer.) |

During penile tumescence, the prepuce also is readily available for examination. If the stallion is excitable, it is often helpful to stand beside the horse with one hand on its withers while beginning to palpate the external genitalia with the other hand (Figure 13-8). The skin of the prepuce should be thin and pliable, with no evidence of inflammatory or proliferative lesions. Developmental abnormalities of the penis and prepuce are rare.

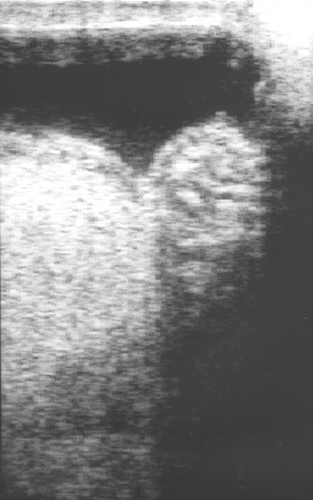

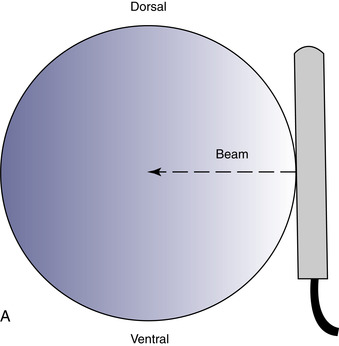

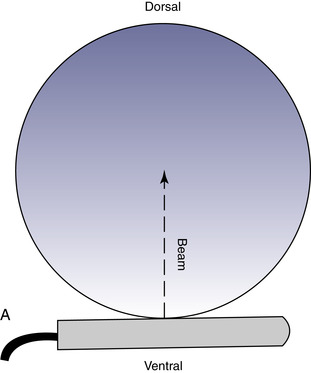

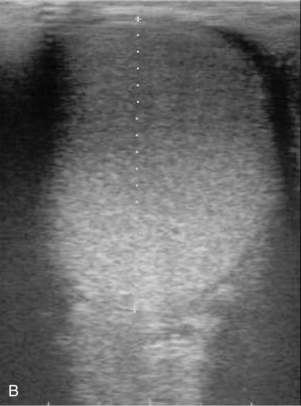

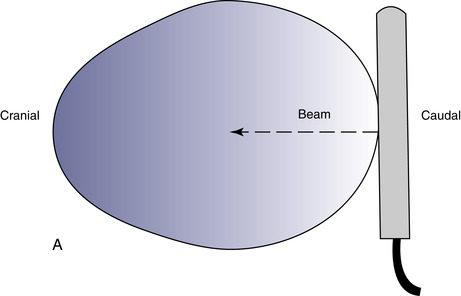

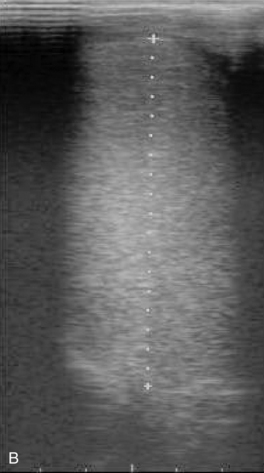

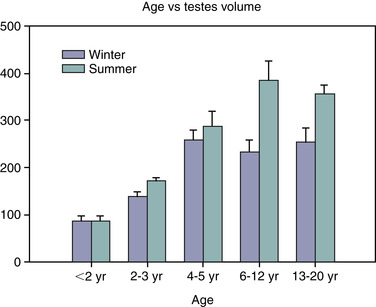

The scrotal skin should be thin and elastic, and the scrotum should have a distinct neck. The scrotum and its contents are normally pendulous (except during cold weather because of contractions of the tunica dartos) but may be drawn toward the body during palpation because of voluntary contractions of the cremaster muscles. Both testes and attached epididymides should be relatively symmetrical and freely movable within their respective scrotal pouches. Size, texture, and position of each testis always should be determined as part of a breeding soundness examination. Testicular size correlates highly with daily sperm production and output, so this measurement helps predict a stallion’s breeding potential. Testes of mature (≥4 years of age), fertile stallions generally are approximately 4.5 to 6 cm in width, 5 to 6.5 cm in height, and 8.5 to 11 cm in length; the total scrotal width (largest measurement taken across both testes and the scrotal skin) (Figure 13-9) generally approximates 9.5 to 11.5 cm (Table 13-1). Transcrotal ultrasonographic examination, including accurate measurement of size, can provide useful information about the normality of the scrotal contents (Figure 13-10 and Figure 13-11). When length, width, and height of each testis are measured in centimeters (Figure 13-12, Figure 13-13 and Figure 13-14), testicular volume (in cc) can be estimated with the formula for an ellipsoid (volume = 0.5233 × width × height × length). Volume should be computed for each testis, and the two volumes are added together to provide total testicular volume. Testicular volumes can be compared with averages established for horses of a similar age to give the examiner an impression of whether the testes are small or not (Figure 13-15). The total testicular volume (TV) in cc can also be used to predict the range of expected daily sperm output (DSO) with the following formula:

| TSW, Total scrotal width; LTW, left testis width; RTW, right testis width. | |||

| Age | TSW | LTW | RTW |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 to 3 yr | 9.6 ± 0.8 cm | 5.5 ± 0.5 cm | 5.3 ± 0.5 cm |

| 4 to 6 yr | 10.0 ± 0.7 cm | 5.7 ± 0.4 cm | 5.5 ± 0.5 cm |

| ≥7 yr | 10.9 ± 0.7 cm | 6.1 ± 0.4 cm | 6.0 ± 0.5 cm |

|

| Figure 13-15 (Modified from Johnson L, Thompson DL Jr: Biol Reprod 29:777-789, 1983.) |

When predicted DSO is significantly less than actual DSO, low spermatogenic efficiency from testicular dysfunction should be suspected. Low spermatogenic efficiency is associated with increased degeneration of testicular germ cells, which can contribute to ejaculation of low numbers of normal sperm.

In addition to its use in obtaining accurate testicular measurements, ultrasonography can be used to detect intratesticular masses and intrascrotal fluid accumulations and to examine the cavernous spaces of the penis (see Chapter 16). Ultrasonography is also a useful adjunct to examination per rectum (e.g., for evaluation of the accessory genital glands or abdominal/inguinal exploration for an undescended testis in a stallion suspected of being cryptorchid).

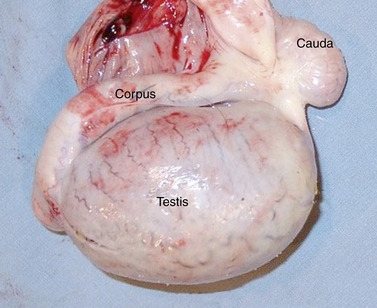

Both testes should be oval, with a smooth regular outline and a slightly turgid, resilient texture. The orientation of each testis within the scrotum can be determined accurately via palpation of the attached epididymis. The epididymis normally is palpable in its entirety as it courses over the dorsolateral surface of the testis; however, identification of its borders is sometimes difficult (Figure 13-16). The caudal ligament of the epididymis, a remnant of the gubernaculum, remains palpable during adult life as a small (∼1 cm) fibrous nodule adjacent to the epididymal tail, which, itself, is attached to the caudal pole of the testis. This remnant serves as a landmark for determination of testicular orientation within the scrotum.

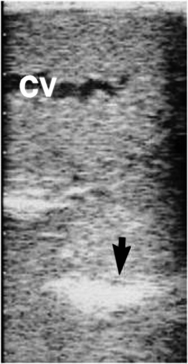

Exploration of the spermatic cord is possible via palpation through the neck of the scrotum, although its specific contents often are not definable. Transcrotal ultrasound examination can also be used to visualize these structures. Spermatic cords should be of equal size and uniform diameter (2 to 3 cm). Acute pain in this area usually is associated with inguinal herniation or torsion of the spermatic cord (see Figures 16-21 and 16-23). Inguinal herniation can usually be confirmed with ultrasonography, which reveals some degree of hydrocele (anechoic fluid accumulation between parietal and vaginal tunics) with hyperechoic gut wall patterns, in which fluid within the bowel lumen is sometimes visible (see Figure 16-20). Transrectal palpation or ultrasonography of internal inguinal rings confirms the herniation. Torsion of the spermatic cord can result in congestion of the affected testis (palpably turgid and slightly hyperechoic) with thickening and engorgement of the spermatic cord from vascular obstruction (see Chapter 16).

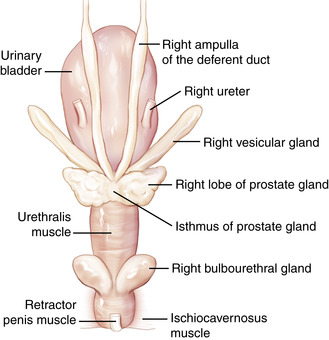

Internal Genitalia

The internal genital organs (Figure 13-17) can be examined via palpation per rectum. Although adequate restraint is of paramount importance to this procedure, minimal but effective restraint is the key to a safe examination and varies from stallion to stallion. The disposition of the stallion should be determined at the onset, and the examination should be canceled if the risk factor is high. Such precautions protect both the stallion and the operator from severe injury. Before the examination, the stallion should be placed in a stock, if available. Ideally, the stock should be equipped with a solid rear door to help prevent leg extension if the stallion decides to kick. The height of the door should be level with the mid-gaskin region of the stallion’s hindquarters.

|

| Figure 13-17 (Modified from Varner DD, Schumacher J, Blanchard TL, et al: Diseases and management of breeding stallions, St Louis, 1991, Mosby.) |

Higher doors can damage the operator’s arm if a stallion squats abruptly while the operator’s arm is in the rectum. Lower doors permit the stallion to kick over this barrier. Poorly designed doors do not protect the examiner and increase the likelihood of injury to the stallion. If necessary, a twitch also can be placed on the stallion’s muzzle for additional restraint. Sedation or tranquilization may be necessary to adequately restrain an anxious stallion. Remember, overrestraint can be as dangerous to the stallion and the operator as underrestraint.

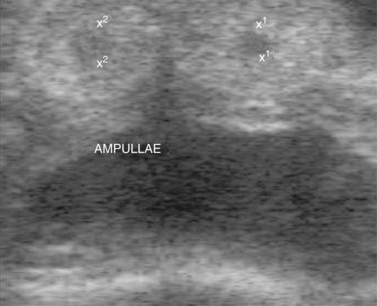

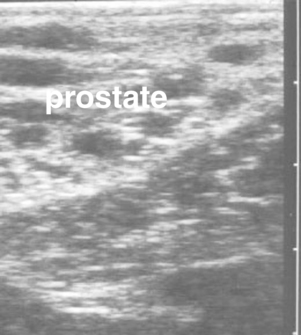

The hand should be well lubricated, and all manure in the rectum and distal colon should be removed before evaluation of pelvic and abdominal structures is attempted. The two vaginal rings (abdominal orifices of the inguinal canals) are palpable as slit-like openings approximately a hand’s breadth ventrolateral to the pelvic brim (Figure 13-18). The deferent duct and pulse of the testicular artery usually can be detected at the opening. The site is evaluated for size and for evidence of adhesions or herniation of viscera. The diameter of the opening is normally 2 to 3 cm. A larger opening may predispose the stallion to inguinal herniation or scrotal hydrocele. Some of the accessory genital organs (i.e., the ampullae and bilobed prostate gland) are also readily detected via palpation per rectum and transrectal ultrasonography (Figure 13-19, Figure 13-20 and Figure 13-21). Lesions of the accessory genital glands, however, are uncommon in stallions.

|

| Figure 13-18 |

OBSERVATION OF LIBIDO AND MATING ABILITY

Excellent semen quality in a breeding prospect is inconsequential unless that stallion also has the desire and ability to deliver the semen to the mare’s reproductive tract or an artificial vagina. Sexual behavior can be evaluated by bringing the stallion in contact with a mare displaying behavioral estrus. Typically, a stallion with good libido shows immediate and intense desire for the mare, manifested by restlessness, pawing, vocalization, and intimate precopulatory activity, such as sniffing, licking, and nipping the mare; exhibition of the flehmen reaction (curling of the upper lip, primarily a response to sniffing of the mare’s genitalia or urine); and development of an erection (Figure 13-22). The onset, intensity, and duration of this courtship phase are affected by the stallion’s genetic makeup, learned behavior (through both positive and negative experiences), seasonal variation, and disease. A common cause for reduced or arrested libido in stallions is mismanagement, especially overuse or repetitive abusive punishment for expression of sexual interest. Length of the courtship phase and number of mounts necessary for ejaculation tend to increase in winter compared with summer. The physiologic mechanisms of stallion sexual behavior are not well understood but involve an intricate relationship between endocrine and neural systems.

|

| Figure 13-22 (From Varner DD, Schumacher J, Blanchard TL, et al: Diseases and management of breeding stallions, St Louis, 1991, Mosby.) |

The ability of a stallion to copulate normally (develop an erection, mount without hesitation, insert the penis, provide intravaginal thrusts, and ejaculate) should be assessed before the stallion is considered to be a satisfactory prospect for breeding. The most common physical abnormality associated with inability to mount is hind limb lameness (e.g., degenerative arthritis of the hock or stifle or even chronic laminitis). The specific cause of erection or ejaculatory failure, unrelated to psychologic malfunction, can be difficult to determine. Penile injuries, spinal cord lesions, and idiopathic organic dysfunctions can lead to impotence. For a thorough discussion of sexual behavior or ejaculatory dysfunction, the reader is referred to McDonnell (1992a, 1992b).

EXAMINATION FOR VENEREAL DISEASE

Several pathogenic microorganisms are transmitted by sexual contact, including bacteria, viruses, and protozoa. The role of fungi and Chlamydia, Mycoplasma, and Ureaplasma spp. in equine venereal disease is unknown but is not considered to be significant. Depending on the etiologic agent involved, venereal disease may manifest itself through overt clinical signs in the stallion, but more commonly, infected stallions are asymptomatic carriers.

Bacterial Genital Infections

Superficial bacterial colonization of the equine prepuce, penis, and distal urethra results in unavoidable contamination of the mare’s reproductive tract during coitus. A variety of environmental bacteria can be isolated from these sites, many of which contribute to the normal nonpathogenic bacterial flora of healthy stallions. These commensal bacteria tend to prevent overpopulation of the external genitalia with potentially harmful organisms (Klebsiella pneumoniae or Pseudomonas aeruginosa). Mismanagement of breeding stallions (through repeated penile washings with soaps or disinfectants or poor selection and upkeep of bedding) may convert the bacterial population on the surface of the penis from a mixed group of harmless bacteria to a population teeming with potential pathogens. The external genitalia of some stallions harbor large numbers of opportunistic bacteria. However, most bacteria are not considered pathogens unless they are recovered serially in heavy growth or unless postbreeding endometritis with the organism results in mares that have been bred to the stallion. The organism that causes contagious equine metritis, Taylorella equigenitalis, represents the only known bacterium capable of consistently producing venereal disease in horses. The stallion serves as a lesionless carrier of this disease, harboring the bacteria on its external genitalia, with subsequent horizontal transmission to the mare’s reproductive tract at breeding.

Documentation of a bacterial infection depends on serial isolation of a pathogen, preferably in large numbers and in relatively pure culture. The exception is culture of T. equigenitalis, for which a single isolation is considered diagnostic (tests for T. equigenitalis must be conducted by an accredited veterinarian under the direction of a state or federal veterinarian). To identify organisms on the exterior of the penis or prepuce, swabbings of these areas should be taken for bacteriologic culture before the penis is cleansed to obtain urethral swabbings. Ideally, specimens should be retrieved from the fossa glandis, urethral sinus, free portion of the penile body, and folds of the external prepuce to provide an overall perspective of the microbial population. The stallion should be placed near a mare in estrus to achieve an erection and facilitate procurement of these samples for culture.

Internal Genital Infections

Internal genital infections in the stallion are rare but when they occur, are most often associated with seminal vesiculitis. Such infections are sometimes associated with hemospermia. Accumulation of leukocytes and the inciting bacteria in ejaculates is typical for stallions with internal genital infections.

If one is to gain insight into the cause of a possible infection of the internal genital tract, the penis and prepuce of the stallion should be washed meticulously with a surgical scrub before collection of appropriate samples for culture. Particular attention is given to removal of debris and organisms from the glans penis and fossa glandis. A thorough rinse should follow the scrub, and the procedure should be repeated twice. After the final rinse, the penis is dried thoroughly to ensure that the urethral orifice is not contaminated. Briskly rubbing the glans penis during the washing process usually stimulates secretion of clear fluid (the presperm fraction of ejaculate), originating from the urethral or bulbourethral glands, into the urethral lumen. This procedure helps remove any bacterial contaminants that may have gained access via the external urethral orifice from the urethral lumen. Some of this fluid may be collected for culture and cytologic examination if an infection of the urethra or bulbourethral glands is suspected. A cotton swab is inserted 3 to 5 cm into the distal urethra to procure a sample for bacterial culture before semen collection (preejaculate swab) (Figure 13-23).

|

| Figure 13-23 (From Varner DD, Schumacher J, Blanchard TL, et al: Diseases and management of breeding stallions, St Louis, 1991, Mosby.) |

After collection of semen, the distal urethra is swabbed again immediately on removal of the penis from the artificial vagina; the urethral opening should not be contaminated before or during the swabbing process. Semen also can be sampled for bacteriologic culture, realizing that the semen has passed through the artificial vagina contaminated by the surface of the stallion’s penis during thrusting. Collection of semen with an open-ended artificial vagina (Figure 13-24) minimizes contamination of the semen with organisms still residing on the exterior of the penis. Swabbings of semen collected into sterile containers with the open-ended artificial vagina are less likely to be contaminated and thus are more likely to yield meaningful cultures.

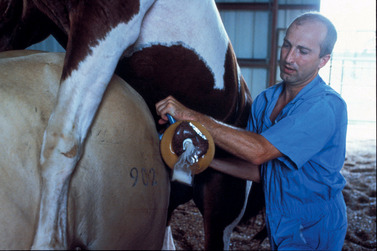

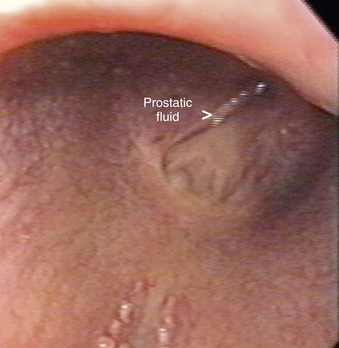

Vesicular gland fluid can be collected selectively for culture by first teasing the stallion vigorously to distend the lumen of these bladder-like glands with secretions. After aseptic preparation of the penis and distal urethra, a 1-cm × 100-cm sterile catheter with an inflatable cuff is passed into the urethra to the level of the seminal colliculus (origin of the excretory ducts of the vesicular glands). The cuff is inflated, and the fluid in each vesicular gland is expressed manually per rectum for collection and study (Figure 13-25). Secretions from the prostate gland, ampullae, and ductus deferens may be cultured by swabbing semen collected in the first “spurt” or “jet” of an ejaculate with an open-ended artificial vagina, because this fraction of the ejaculate contains secretions originating primarily from these sites. Alternatively, the prostate and bulbourethral glands can be identified via transrectal ultrasonographic examination. After each gland is identified, the probe is retracted 2 to 3 inches while the digits are used to apply pressure to the gland of interest. Fluid expressed from the gland can be retrieved through a preplaced catheter or endoscope (Figure 13-26), and the gland can be immediately rescanned to confirm that fluid was expressed.

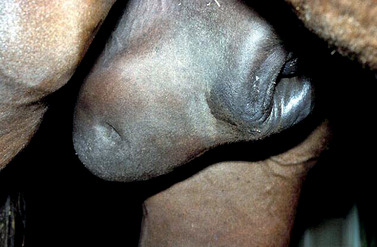

Infections that originate from the epididymides or testes usually induce changes that are palpable through the scrotum, except in severe cases in which scrotal edema is pronounced (Figure 13-27). The incriminating organism usually can be recovered from the semen, along with inflammatory cells recognized on cytologic examination of stained semen smears. Chronic epididymitis or orchitis may result in azoospermia, as fibrous tissue proliferation can obstruct the epididymal duct. Adhesion formation between parietal and visceral tunics prevents free movement of the gonad within the scrotal tunics.

|

| Figure 13-27 |

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree