CHAPTER 10. Dystocia and Postparturient Disease

OBJECTIVES

While studying the information covered in this chapter, the reader should attempt to:

■ Acquire a working understanding of maternal and fetal contributions to dystocia and those factors that contribute to postparturient abnormalities in the mare.

■ Acquire a working knowledge of procedures used to diagnose and relieve dystocia in the mare.

■ Acquire a working knowledge of procedures used to diagnose and methodologies used to treat abnormalities of the postparturient period in the mare.

STUDY QUESTIONS

1. List equipment necessary to correct dystocia in the mare.

2. Describe procedures used to diagnose the cause of dystocia in the mare.

3. Define the following terms:

a. Dystocia

b. Fetal presentation

c. Fetal position

d. Fetal posture

e. Mutation

f. Repulsion

g. Delivery via traction

4. Describe the more common obstetric procedures used to correct dystocia in the mare via mutation and delivery via traction.

5. Describe proper treatment of the following postparturient abnormalities in the mare:

a. Retained placenta

b. Metritis

c. Laminitis

d. Uterine prolapse

e. Invagination of the uterine horn

f. Uterine rupture

g. Ruptured uterine or ovarian artery

h. Other postparturient hemorrhages

Dystocia and postparturient disease are uncommon in the mare; however, when they do occur, they may carry a guarded prognosis for life or future fertility in affected mares. Prompt, sound clinical management of dystocia, retained placenta, and other postparturient disorders can preserve the breeding potential of valuable mares.

DYSTOCIA

For better recognition of dystocia, the processes and events of normal delivery must be well understood. Refer to Chapter 9 for a review of normal progression through the three stages of parturition. If either the first or the second stage of parturition is prolonged or not progressing, dystocia is possible. Prompt veterinary examination is indicated to preserve the life of the foal and mare and to prevent injury to the mare’s reproductive tract.

Obstetric Equipment and Lubricant

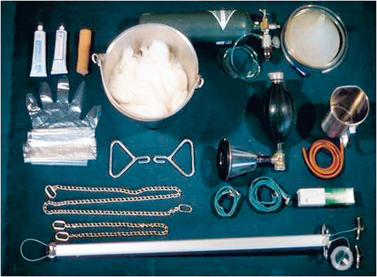

High-quality, clean (preferably sterile) obstetric equipment and lubricant should be readily available. Equipment should include, at a minimum, lubricant, obstetric chains or straps, obstetric handles, a bucket, cotton or paper towels, tail wrap, and disinfectant soap (Figure 10-1). For the special equipment needed to perform a fetotomy, the reader is referred to the monograph by Bierschwal and de Bois (1972).

When minimal obstetric manipulations are necessary, the authors sometimes apply a small amount of polyethylene polymer powder (J-Lube, Jorgensen Laboratories Loveland, CO) to the birth canal of the mare. The powder adheres to mucosal membranes, which provides excellent short-term lubrication for extracting the fetus. Note, however, that this product should be avoided if any chance of uterine rupture exists or if a cesarean section may be needed because even small amounts of J-lube contamination of the peritoneum can be fatal (Frazer et al., 2004). Liquid lubricants (e.g., carboxymethylcellulose solution) provide good protection to the fetus and genital tract and can be pumped into the uterine lumen and around the fetus through a sterile stomach tube. Lubricant solution can be sterilized in gallon containers before use, or 0.5 to 1 tablespoon of chlorhexidine solution can be mixed with each gallon of lubricant as a disinfectant. This amount of disinfectant does not seem to irritate the genital tract. Pumping lubricant into the uterine lumen provides some uterine distention that facilitates manipulation of the fetus. For fetotomy, petroleum jelly can be applied to the fetus and birth canal for extra protection against physical injury during the procedure.

Examination of the Mare

If possible, the mare should be standing for the initial examination. The examination is done in a clean environment with good footing for the mare and the veterinarian. The tail is wrapped and tied to the side, and the perineal area and rump are thoroughly scrubbed with an antiseptic soap and dried. If straining is a problem, the initial examination is made while the mare is being slowly walked. When necessary, a local anesthetic can be injected into the caudal epidural space to control straining. After the hair over the site of injection (usually coccygeal vertebrae 1 and 2, Cy1-Cy2) is clipped, the skin is scrubbed and disinfected. Lidocaine (1.0 to 1.25 mL of 2% lidocaine per 100 kg of body weight) can then be administered in the caudal epidural space to provide perineal analgesia and control straining. We prefer to use a combination of xylazine (35 mg/500 kg of body weight), Carbocaine-V (Pharmacia & Upjohn Co, New York, NY) (2.6 mL of 2% mepivacaine hydrochloride/500 kg of body weight), and sterile 0.9% NaCl solution (sufficient quantity [qs] to 7.0 to 8.0 mL/500 kg of body weight) for epidural anesthesia. The rationale for use of this combination is that perineal analgesia is optimized while the risk of hind limb ataxia associated with higher doses of local anesthetics is reduced. Note that because 30 minutes may be required for full anesthetic effect, valuable time can be lost if an epidural is used when a live fetus is present, which can result in the delivery of a compromised foal or stillborn fetus. In some cases, general anesthesia (xylazine, 1.0 mg/kg, intravenously [IV], followed by ketamine, 2 mg/kg, IV) may be necessary to facilitate obstetric procedures.

The hands and arms of the veterinarian are scrubbed with a disinfectant soap and then rinsed before entry into the birth canal. Sterile plastic sleeves can also be worn. The fetus is thoroughly examined to assess presentation, position, and posture and for the presence of any congenital abnormalities, such as contracted tendons, that might contribute to dystocia. An attempt is made to determine whether the fetus is alive with stimulation of reflex movements or with detection of a heartbeat or umbilical pulse if either the fetal thorax or umbilicus is within reach. Evidence of trauma that may indicate a previous attempt to deliver or allude to the duration of dystocia is noted.

For descriptive purposes, the reader should be familiar with terms used to describe the fetus at the time of its entrance into the birth canal or pelvis. Presentation refers to the relationship of the spinal axis of the fetus to that of the dam (longitudinal or transverse) and the portion of the fetus entering the pelvic cavity (head, anterior or cranial; or tail, posterior or caudal) in longitudinal presentations or ventral or dorsal in transverse presentations. Position refers to the relationship of the dorsum of the fetus in longitudinal presentation or the head in transverse presentation to the quadrants of the maternal pelvis (sacrum, right ilium, left ilium, or pubis). Posture refers to the relationship of the fetal extremities (head, neck, and limbs) to the body of the fetus; they may be flexed, extended, or retained beneath or above the fetus. The normal presentation, position, and posture of the equine fetus during parturition are anterior-longitudinal, dorsosacral, and with the head, neck, and forelimbs extended, respectively. Fetal postural abnormalities are the most common cause of dystocia in the mare. Equine fetuses are predisposed to postural abnormalities because of the long fetal extremities. Structural abnormalities of the fetus, such as hydrocephalus, may also result in dystocia. Caudal and particularly transverse fetal presentations are associated with a greatly increased incidence of fetal malformations (particularly contractures) that contribute to dystocia. Fetal death or severe compromise prevents the fetus from taking an active part in positioning for delivery, thereby contributing to dystocia.

Accurate assessments of fetal presentation, position, and posture; the presence of fetal abnormalities; whether the fetus is alive; the condition of the genital tract; and the general condition of the mare are necessary to formulate a plan for delivery. Unless structural abnormalities of the fetus are present, mutation and delivery via traction are often possible. If dystocia is prolonged, the birth canal and uterus may become contracted, edematous, and devoid of fetal fluids, necessitating the choice of an alternate route of delivery.

Delivery via Mutation and Traction

Mutation refers to manipulation of the fetus to return it to normal presentation, position, and posture for facilitation of delivery. It is helpful to first repel the fetus from the maternal pelvis into the abdominal cavity (where more space is available for repositioning and correction of fetal malposture). Additional room can sometimes be gained by pumping 1 or 2 gal of warm liquid lubricant into the uterine lumen and around the fetus. To avoid uterine rupture, obstetric manipulations must not be overly vigorous. Repulsion is not attempted if the uterus is devoid of fetal fluids, dry, and contracted; an alternative form of delivery (cesarean section) is chosen. General anesthesia and elevation of the hindquarters of the mare often result in sufficient gravitational repulsion and elimination of straining to permit mutation and delivery of the fetus.

In countries in which injectable clenbuterol (Ventipulmin Solution, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Burlington, Ontario) is available, slow intravenous administration of 0.17 to 0.35 mg/454 kg of body weight induces uterine relaxation sufficient to permit safer repulsion and repositioning of the fetus. Although this drug is antagonistic to the effects of prostaglandin-F 2α (PGF 2α) and oxytocin, its use apparently does not result in an increased incidence of uterine prolapse or retained placenta. Clamping the dorsal vulvar labia for 6 to 8 hours after correction of dystocia with this drug may, however, be indicated to reduce the chance of prolapse. More recently, practitioners have started using Buscopan (N-butylscopolammonium bromide, Boehringer-Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Ridgefield, CT) to relax the uterus and facilitate obstetric procedures.

Correction of Malposture

Regardless of presentation, the limbs of a full-term fetus must be extended to permit passage through the birth canal. To correct carpal or hock flexion, the flexed carpus or hock is repelled out of the pelvis while traction is applied to the foot until it is fully extended. Traction can either be applied entirely by hand or be assisted by first placing an obstetric chain or strap around the pastern and having an assistant pull on it while the other hand simultaneously repels the proximal portion of the limb. If adequate room is available, this procedure can sometimes be accomplished by introducing both arms into the birth canal. One hand should be cupped over the foot as it is brought outward to prevent uterine rupture when traction is applied on the distal end of a flexed limb.

Anterior presentations with deviations of the head and neck commonly lead to dystocia in mares. For correction of lateral or ventral head posture, the fetus is repelled and the jaw or muzzle of the foal is grasped and pulled toward the pelvic inlet. To gain more room for this procedure, one forelimb can first be placed in carpal flexion after a chain is placed around the pastern. The chain is helpful for correcting the carpal flexion after the head is replaced in the pelvic inlet. Securing a snare around the lower jaw may correct alignment of the head and neck, provided minimal traction is applied. Alternatively, a loop of obstetric chain can be secured to the head by placing it through the mouth and over the poll. Again, minimal traction should be applied and care should be taken to prevent damage to the uterus from incisors through a gaping mouth created with this technique.

When the fetus is presented normally (i.e., anterior longitudinal presentation, dorsosacral position, with the forelimbs, head, and neck extended), delivery can proceed. If the fetus is presented posteriorly, delivery can proceed after the hind limbs are extended. Traction straps or chains can be placed around the fetal pasterns, with the eye of the straps on the dorsal (extensor) aspect of the limbs. Placement of two loops on each limb, with the first encircling the distal cannon bone (immediately above the fetlock) and the second encircling the pastern (Figure 10-2), helps prevent damage to the distal limb when forceful traction is applied. Traction is gradual and smooth, applied only during the dam’s abdominal press. With anterior-longitudinal presentation, traction is applied such that one forelimb precedes the other until the shoulders travel through the birth canal.

Any impediments to delivery are corrected promptly to allow delivery to continue because the umbilicus may be compressed, thus restricting blood supply to the fetus. In posterior presentations, rupture or impaction of the umbilicus quickly leads to fetal anoxia, so delivery must be accomplished quickly to avoid fetal asphyxia.

If the fetus is in posterior presentation with bilateral hip flexion ( breech presentation) or transverse presentation, the chances of delivery of a viable foal after dystocia are greatly reduced. The casual observer is frequently unaware that the mare is in labor in these cases because abdominal straining is often weak. More detailed procedures for mutation and delivery via traction are reviewed by Roberts (1986).

If the dystocia cannot be corrected within 10 to 15 minutes via fetal manipulations with the mare standing, anesthetization of the mare may increase the chance of a successful delivery. After induction of anesthesia, the mare is positioned in dorsal recumbency and the hindquarters are elevated with a hoist until the long axis of the mare is at a 30-degree angle to the floor or ground. If the mare is anesthetized in the field, placement of the mare in a head-down position on an incline often works as well. This procedure eliminates abdominal straining and increases the intraabdominal space for easier manipulation of the fetus.

If the fetus is dead and cannot be delivered via mutation and traction, an alternative method of delivery must be chosen. Fetotomy may provide a more satisfactory alternative than cesarean section in such cases. When fetotomy is correctly performed, major abdominal surgery is avoided, which results in a shorter recovery time for the mare and less aftercare than with cesarean section. The most common indication for fetotomy is to remove the head and neck of a dead fetus when manual correction of lateral or ventral head deviation is difficult. However, fetotomy should be avoided, if possible, in mares with protracted involution and fetal emphysema (because room to manipulate the fetus and fetatome is severely constrained), or if more than partial dismemberment (one or two cuts) of the fetus is necessary, to avoid the potential for severe damage to the genital tract.

Cesarean section is indicated if attempts to deliver a foal per vagina jeopardize the foal or mare or are apt to impair the mare’s subsequent fertility. Such situations include certain types of malpresentation; emphysematous fetuses; deformed fetuses; certain types of uterine torsion; and abnormalities of the dam’s pelvis, cervix, or vagina. Extremely large foals or small dams might also necessitate cesarean section for correction of dystocia. Refer to citations in the Bibliography for discussion of equipment, procedures, and techniques for performing percutaneous fetotomy and cesarean section.

Uterine Torsion

Uterine torsion occurs uncommonly in mares; however, it does account for a significant percentage of serious equine dystocias. Uterine torsion occurs more commonly in preterm mares (5 to 8 months of gestation) than in term mares. Preterm mares with uterine torsion exhibit signs of intermittent, unresponsive colic. The condition is diagnosed by determining displacement of the tense broad ligaments via palpation per rectum. Identification of the ovaries is helpful in determining that “twisted” structures are indeed the uterus and broad ligaments. Diagnostic methods are the same for preterm and term uterine torsion. The reader is referred to Chapter 8 for discussion of diagnosis and treatment of uterine torsion in preterm mares. Uterine torsion very rarely occurs at term with the cervix dilated. If the cervix is open, correction of the torsion may be possible in a standing mare by grasping the fetus ventrolaterally with the arm resting on the pelvic floor and then rocking the fetus to impart momentum until it can be lifted upward and rotated into (opposite to) the direction of the uterine twist. If this method is successful, the fetus and uterus rotate into the normal position, and the fetus can be delivered as soon as the cervix becomes fully dilated.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree