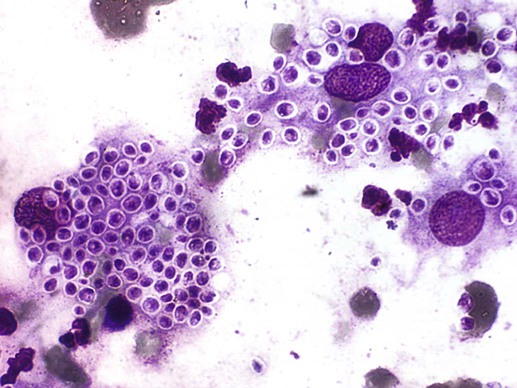

Tânia Maria Pacheco Schubach, Rodrigo Caldas Menezes and Bodo Wanke* Sporotrichosis is a mycotic disease caused by the thermal dimorphic fungus Sporothrix schenckii. It has been reported in people, chimpanzees, cats, dogs, pigs, mice, rats, hamsters, mules, horses, donkeys, cattle, goats, fox, armadillos, dolphins, camels, and fowl.11,14,14 S. schenckii is widespread in nature and has been isolated as a saprobe from senescent or dead vegetation, such as thorns, hay, straw, sphagnum moss, wood, and soil rich in decaying organic matter. The organism is most prevalent in warm, tropical and subtropical climate regions. It grows in nature or on cultures at 25° C as a mycelium and converts to small budding yeastlike cells in mammal tissues or on cultures at 37° C. Infectivity may result as a selective process of strains adapted to grow at temperatures higher than 35° C.39 Although only one species of Sporothrix has been classically identified, modern phylogenetic studies suggest that distinct species may occur in different geographic regions.53 Generally, the infection results from direct inoculation of the fungus into skin via contact with contaminated plants or soil, or less frequently, by inhalation of conidia. Zoonotic transmission occurs through bites or scratches of animals such as mice, armadillos, squirrels, cats, and dogs.39,59 The teeth and claws of most animals may become contaminated from contact with the environment. However, cats are the only animals that are a proven reservoir of the organism, as demonstrated by isolation of S. schenckii from skin lesions, which are rich in fungi, and from nasal and oral cavities and nails of cats with sporotrichosis.87 The mobility of cats in dwellings and surroundings, their habit of scratching vegetation, and their fighting behavior, especially in male cats, facilitates dispersal of the fungus in the environment. Canine sporotrichosis can be acquired during hunting activities with possible introduction of the organism through thorn injuries or wood splinters. However, in the ongoing sporotrichosis epidemic observed in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the most frequent form of transmission to dogs was through cat’s scratches produced during their fights.88 Sporotrichosis is distributed worldwide and at present is rare in Europe, but frequent in the Americas, Africa, Japan, and Australasia. In Latin America it is the most common subcutaneous mycosis in people.11 Epidemics involving great numbers of people or wide geographic regions are rare and usually related to a common source of infection in the environment such as wood timbers and sphagnum moss.16,30,30 There were no reports of epizootics before a cat-transmitted epidemic was reported in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.81 In that study, which ranged from 1998 to 2004, 759 humans, 64 dogs, and 1503 cats were diagnosed with sporotrichosis. By December, 2006, a total of 1137 humans from the same with culture-proven sporotrichosis had been recorded, so far representing the largest epidemic of this mycosis in the form of a zoonosis.81 Following inoculation, the fungus penetrates into deeper layers of tissue where it converts into the yeast like form. It can remain in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue at the inoculation site, spread up regional lymphatics and produce lymphangitis and lymphadenitis, or disseminate systemically through blood vessels. Furthermore, in cats, the high frequency of respiratory signs and pulmonary and nasal mucosal lesions, in addition to the isolation of S. schenckii from bronchoalveolar lavage washings and from the lungs of necropsied animals, suggests the epidemiologic importance not only of the cutaneous trauma route, but also of the inhalatory route in the infection.46,84 Multiple skin lesions can occur because of self-trauma, grooming, and hematogenous dissemination from the lungs or perhaps from the initial skin lesion.87 The classification of clinical presentations used for humans includes several forms: lymphocutaneous, fixed cutaneous, mucocutaneous, extracutaneous, and disseminated.71 These categories are difficult to transpose to sporotrichosis in dogs and cats because frequently they have more than one of these forms simultaneously. Although the cutaneous lymphatic form (Fig. 61-1) is the most frequently seen clinical presentation in humans, this is not the case with cats, and possibly not with dogs.87,88 The most common lesions in dogs and cats are skin nodules and ulcers, with frequent mucosal involvement. The initial lesions are firm subcutaneous nodules that slowly soften, generally draining purulent or seropurulent content, and progress to form exudative ulcers with slightly elevated well-defined rims. In addition, dogs and cats may have extracutaneous, mainly respiratory signs, such as sneezing, nasal discharge, and dyspnea, followed by lymphadenomegaly. Other clinical signs that may be observed are anorexia, vomiting, weight loss, cough, fever, and dehydration.87,88 Sporotrichosis in dogs, as in humans, is an essentially a benign disease, despite rare osteoarticular and disseminated forms that can develop.35,94 The skin lesions may be solitary or multiple and more frequently located on the head, especially on the nose (Fig. 61-2), followed by the limbs and thorax. In a retrospective study involving 44 dogs, the duration of dermatologic lesions ranged from 2 to 48 weeks.88 The cutaneous lymphatic form was only observed in 3 (6.8%) dogs and was usually associated with regional lymphadenomegaly. Nasal mucosal involvement was present in 9 (20.5%) dogs, with isolated mucosal lesions being detected in 3 (6.8%). Cats are highly susceptible to S. schenckii infection, and the evolution of the disease is usually severe, unlike that which occurs in other species. Presumably because of their behavior, a higher prevalence of disease is found in adult male and sexually intact animals. The spectrum of signs ranges from subclinical infection, to a single skin lesion with spontaneous regression, to fatal systemic forms due to hematogenous dissemination. The most frequent clinical forms are multiple skin and mucosal (conjunctival, nasal, oral, or genital) lesions (Figs. 61-3 and 61-4). In addition to skin and mucosal nodules and ulcers, lymphangitis, regional lymphadenitis, and extensive zones of necrosis that expose muscle and bone can be observed.87 The most affected body parts are the head, especially the nose and ears, tail, and hindlimbs. In a retrospective study involving 347 cats with sporotrichosis, the cutaneous lymphatic form was observed in only 19.3% of cats, whereas multiple skin lesions occurred in 39.5% of cases and involvement of mucosa of the upper respiratory and digestive tracts occurred in 34.9%.87 Respiratory signs observed in 44.4% of cats (including three cats without skin lesions) were the most frequent extracutaneous signs.87 Although no clinical signs suggestive of a septic syndrome were observed, S. schenckii organisms were commonly cultured both from the peripheral blood of cats with widespread cutaneous lesions and from cats in good general condition with localized lesions.85,86 Some authors believe that the gravity of feline sporotrichosis may be related to immunodepression caused by co-infection with feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) or feline leukemia virus (FeLV). However, there are few reports to support this theory.15 No significant differences in clinical signs or laboratory findings were found between cats that were co-infected with sporotrichosis and FIV/FeLV and cats that were not.87 In cats with systemic sporotrichosis, dissemination via blood was not associated with the immunodeficiency caused by FIV/FeLV.84 Additionally, in contrast to the disease in humans, the high frequency of sporotrichosis without apparent immunosuppression supports the assumption that this disease develops in a different manner in cats.87 Clinical signs in dogs and cats are nonspecific, and differential diagnosis should include bacterial pyoderma, phaeohyphomycosis, mycobacteriosis, nocardiosis, actinomycosis, cryptococcosis, eosinophilic granuloma complex, foreign body, neoplasia (mainly squamous cell carcinoma and lymphoma), immune-mediated diseases (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris), severe allergic diseases (e.g., mosquito bites), or drug eruption.51,68 In Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the main differential diagnosis, especially in dogs and humans, is American tegumentary leishmaniasis.79 Although clinical signs, patient history, and epidemiologic data can suggest sporotrichosis, definitive diagnosis depends on cultural isolation of S. schenckii. However, cytology, histopathology, and immunohistochemical testing are very useful routine tools for the preliminary diagnosis. Hematologic and serum biochemical abnormalities are nonspecific.84,87,87 Samples should be collected according to clinical conditions and features of the lesions and should include swab specimens of the nasal cavities, exudative lesions, and purulent or seropurulent content aspirated from nonulcerated abscesses, as well as incisional skin biopsy specimens.79,87 The swabs should be seeded on Sabouraud’s agar and Mycosel agar, where possible, and then sent to the laboratory, at room temperature for mycologic examination. The skin biopsies should be obtained from borders of active lesions with a 3- to 4-mm surgical punch. Two tissue samples can be collected, one fixed in 10% buffered formalin for histopathology and immunohistochemical tests and the second kept in a sterile glass flask with sterile saline and antibacterial agent and transported at refrigerated temperatures (4° C) to a diagnostic laboratory for fungal culture.46 The best results for fungal isolation are obtained from skin biopsies from cats or dogs.87,88 For cytologic examination, suitable samples can be obtained by impression smears on glass slides for microscopy of ulcerated skin or exudates, smears of swab specimens, tissue samples from biopsy, or skin scrapings, and also by aspiration of abscesses and nodules.79,8,8 To diagnose dissemination, whole blood can be directly seeded in blood culture flasks.86 Another sample useful for the diagnosis of systemic involvement in vivo is bronchoalveolar lavage.46 At necropsy, tissue samples can be collected to mycology, cytology, histopathology, and immunohistochemical testing as previously described. This technique is very useful, and relatively accurate, for preliminary diagnosis of sporotrichosis.65a Smears on glass slides stained with Wright’s or Romanowsky-type, or Gomori’s methenamine or Grocott’s silver stain (GSS) will permit good visualization of the yeast cells.10,79 With Wright’s or Romanowsky-type staining, a positive cytologic exam suggestive of S. schenckii shows cigar-shaped to oval or round budding yeastlike organisms of 3 µm to 5 µm by 5 µm to 9 µm, with blue cytoplasm and a single, round, pink nucleus surrounded by a nonstaining cell wall (Fig. 61-5).34,99 These organisms are seen mainly within cytoplasm of macrophages, and in neutrophils and also extracellularly.6,99 Smears prepared from lesions from cats with sporotrichosis usually contain high numbers of yeastlike cells, although in some cases the fungi may be difficult to visualize. In dogs with sporotrichosis, organisms are often scarce.6,79 Other organisms confused with S. schenckii include nonencapsulated forms of Cryptococcus neoformans and Histoplasma capsulatum.10 Apart from the cutaneous and mucosal lesions described in the clinical findings, the main gross lesions in cats are small whitish dots measuring approximately 1 mm in diameter on pleural surface and parenchyma of the lungs and enlargement of lymph nodes.84 Histopathologic findings observed on hematoxylin and eosin stained tissue sections are not disease specific and can be related to other pathogenic fungi and protozoans.58a Therefore, specific histochemical staining techniques such as GSS and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) are needed to identify the structure of S. schenckii.18,87 In addition, serial histologic sections of the same tissue sample may markedly improve the possibility to detect the fungus. The yeast cells suggestive of S. schenckii are oval or cigar-shaped, range in size from 4 µm to 6 µm, generally exhibit a single bud with a narrow base, and are dark staining in GSS and pink in PAS (Fig. 61-6). Pseudohyphae can be seen.101 Histologically, the cutaneous lesions of feline and canine sporotrichosis are characterized by ulcerative and variable but usually intense pyogranulomatous inflammatory reaction in dermis, which can reach the paniculus and subjacent skeletal muscles. Yeastlike cells can be seen inside macrophages and neutrophils and extracellularly in purulent exudate or inflamed areas. In cats with sporotrichosis, the number of Sporothrix organisms is usually high and can be detected in 62% of histopathologic examinations of skin biopsies.19,87,87 However, in dogs with sporotrichosis, the fungus is visualized in tissue specimens in 17% to 42% of cases, and usually the yeastlike forms are rare, as in humans. The GSS-stained specimens showed a higher sensitivity compared to those stained with PAS in the histopathologic diagnosis of canine sporotrichosis, and 58.3% of positively diagnosed cases had a maximum of five fungal elements.58 Asteroid bodies are not reported, and multinucleated giant cells are infrequent in dogs and cats compared to their occurrence in humans.58,79,79 In addition, there is an inverse correlation between the presence of granuloma and the histopathologic finding of S. schenckii in cats and dogs.58,87 The frequency of granulomas is low in cats, about 12% in skin biopsy specimens. However, in dogs, as in humans, well-organized granulomas are frequent and present in 38.2% to 45.2% of animals.5,58,79,87,88 Unlike dogs, systemic involvement is common in cats with mild to moderate mixed inflammatory infiltrate of polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cells and yeastlike structures observed histologically in lungs, liver, spleen, eye, kidney, adrenal glands, and lymph nodes.18,84,84 Immunohistochemistry using fluorescein-conjugated antibodies can be used to identify the yeastlike cells of S. schenckii in the paraffin-embedded tissue from infected animals. Unstained histologic sections are deparaffinized and labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated polyclonal rabbit S. schenckii antiglobulin. This technique provides a quick and specific diagnosis of sporotrichosis and is very useful when multiple fungal cultures are negative and do not correlate with the cytologic and histopathologic findings.34,101 Testing for serum antibodies to the organism such as whole yeast agglutination, latex agglutination, enzyme-based immunoassay, and indirect fluorescent antibody testing can be used20a,100; however, these techniques do not distinguish exposure from active infection, and there may be cross-reactivity with other fungal organisms. The recommended therapeutic schemes have been based on reports of isolated cases or the study of a series of cases with insufficient sample size to compare different drug schemes,66,67 and animal therapy is based on the treatment of human sporotrichosis.40 Sodium iodide (NaI) or potassium iodides (KI) were considered the drugs of choice in human and canine sporotrichosis; however, serious adverse effects have limited their use. Itraconazole (ITZ) is considered the drug of choice in feline (Table 61-1) and human sporotrichosis treatment because of its greater effectiveness and safety when compared to other antifungal agents.40,66,67,99 Other therapeutic options in dogs and cats are ketoconazole (KTZ), terbinafine, local thermotherapy, amphotericin B (AMB), and surgical resection of cutaneous lesions.27,32,32 Treatment should be continued for at least 1 month after apparent clinical cure to prevent recurrence of clinical signs.76,99 Use of glucocorticoids or any immunosuppressive drug is contraindicated both during and after the treatment of the disease, because the disease can worsen or recur.49,76 Any concurrent bacterial infection should be simultaneously treated for 4 to 8 weeks with an appropriate antibacterial to help in the healing of the lesions.73 TABLE 61-1 Drug Therapy for Sporotrichosisa

Sporotrichosis

Etiology and Epidemiology

Pathogenesis

Clinical Findings

Dogs

Cats

Diagnosis

Sample Collection

Cytologic Findings

Pathologic Findings

Immunohistochemical Testing

Serologic Testing

Therapy

Drugb

Species

Dose (mg/kg)c

Route

Interval (hours)

Duration (months)

SSKId

Dog

40

PO

8

≥2

Cat

10–20

PO

12

SSI

Cat

10

PO

12

≥2

Ketoconazole tabletse

Dog and cat

5–10f

PO

24

≥2

Cat

13.5–27.0g

PO

12–24

≥6

Itraconazole capsulesh

Dog and cat

5–10f

PO

12–24

≥2

Cat

8.3–27.7g

PO

12–24

≥6

Itraconazole solutionh

Cat

1.25–1.5

PO

24

≥2

Terbinafinei

Cat

30

PO

24

≥2 ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Sporotrichosis