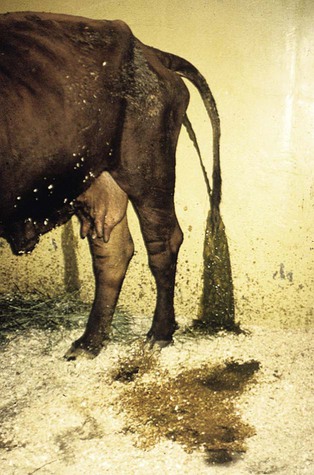

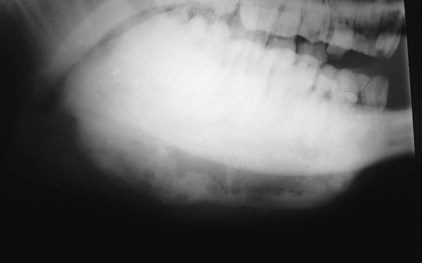

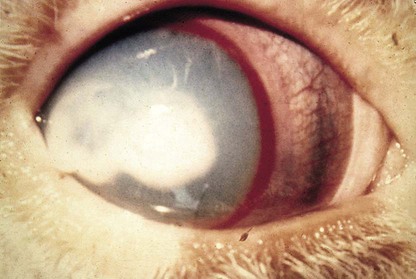

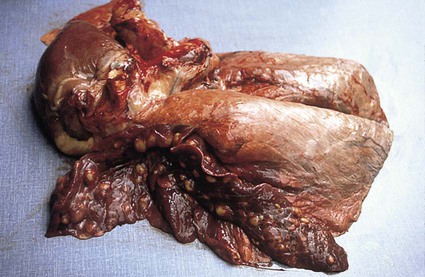

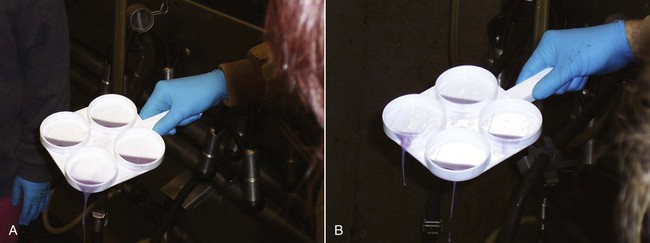

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to • Describe and recognize clinical signs associated with all common bovine diseases • Understand the etiology of the diseases • Understand and describe common treatments for bovine disease • Know the common scientific names of parasites associated with cattle • Know the common vaccinations and their schedules associated with cattle If the veterinarian suspects anthrax in a deceased animal, a necropsy should not be performed. When the bacteria are exposed to oxygen from an open carcass, they form spores that are resistant to extreme temperatures and chemical disinfectants. Diagnosis should be based initially on a blood smear. The disease can be confirmed by laboratory tests and growth of B. anthracis on an agar plate. Differential diagnosis includes bloat, clostridial disease, lightning strike, anaplasmosis, and bacillary hemoglobinuria. When necropsy is performed, the characteristic finding is an enlarged, dark, and soft-textured spleen (Fig. 13-1). The disease often presents in feedlot cattle. Although most animals are found dead in the absence of clinical signs, cases caught early can present acutely with depression and lameness (Fig. 13-2). Upon necropsy, necrotic muscle can be isolated. The necrotic muscle has a distinct rancid smell. Often the affected muscle lies adjacent to normal tissue. The diagnosis is often made based on these characteristic necrotic lesions (Fig. 13-3) and confirmed by fluorescent antibody staining. Calf enteritis is also known as scours (Fig. 13-4). Calf scours is a major cause of death in the first few weeks of life. Calves infected in the first few days of life are often infected with bacteria (e.g., Escherichia coli and Clostridium perfringens). Cattle infected between 10 to 14 days of life are often infected with viruses (e.g., rotavirus and corona virus). Another type of infection that occurs in this age bracket is Cryptosporidium (Fig. 13-5). Salmonella may present at any age. One or more feet may be affected. Cattle may be mild or moderately lame, but severe lameness affecting multiple individuals in a herd is the common presentation. Inflammation and necrotic tissue are present in the affected interdigital clefts and often produce an exudate and characteristic bad odor. Local swelling is common and may cause the claws to spread apart. A skin fissure often develops, with swollen, necrotic skin edges and purulent exudate (Fig. 13-6). The infection may extend to undermine the hoof walls in the areas adjacent to the interdigital infection (Fig. 13-7). The pain causes lameness, with the animal limping or holding the leg up in an attempt to avoid bearing weight. Fever may develop, especially with deep tissue infection. Deep abscesses and infection of the coffin and pastern joints and associated tendons may develop. Clinical signs include continuous or intermittent profuse watery diarrhea and sometimes weight loss (Fig. 13-8). The most important aspect of Johne disease is the economic loss associated with decreased production. Decreases in production can be associated with reduced feed efficiency, decreased milk production, reduced slaughter weights, increased incidence of mastitis, and premature culling. The disease often presents as an abortion storm (Fig. 13-9). Stillbirths, loss of milk production, septicemia, hemoglobinuria (red water disease), weak neonates, and reduced fertility can be seen within infected herds. Periodic ophthalmia (recurrent uveitis) may be seen in an infected horse. Even after resolution of clinical signs, animals can spread leptospirosis in the urine for 10 to 118 days. Upon necropsy, animals infected with L. pomona have swollen, dark kidneys (Fig. 13-10). Diagnosis of the disease is often accomplished by paired serum samples or histopathology. Clinical signs of the disease include fever, facial nerve paralysis, tongue hanging from the mouth (Fig. 13-11), circling (Fig. 13-12), drooping ears, blindness, and abortion. The uterus can also become infected with L. monocytogenes, causing metritis, abortion, stillbirth, neonatal death, and possibly carrier animals. Lumpy jaw is also known as actinomycosis. Lumpy jaw is caused by the bacterium Actinomyces bovis, a gram-positive rod. The bacteria often gain access to the body through the oral cavity when the animal consumes coarse hay or sticks that penetrate the mucosa and allow entrance of the bacteria. Another common entrance point for the bacteria is from skin punctures that occur around the head. The bacteria then travel through the soft tissue to the adjacent bone and develop into granulomatous masses (Fig. 13-13). Clinical signs include mass formation on the mandible or maxillary jaw (Figs. 13-14 and 13-15). The animal is often unaffected until the mass interferes with mastication. Once mastication is affected, the animal often loses weight quickly and is culled. Treatment is often ineffective, although attempts can be made with antibiotics and debridement. Mastitis (inflammation of the mammary gland) causes an estimated loss of more than $1 billion to the dairy industry in the United States each year (Fig. 13-16). Diagnosis and treatment of mastitis is critical for the health of dairy animals and for the successful production of milk that is safe for human consumption. Nondairy animals may also develop mastitis and suffer from the related pain and inflammation (Fig. 13-17). Mastitis is almost always caused by bacterial infection (septic mastitis), but inflammation without infection may occur if a teat or udder is traumatically injured (e.g., laceration, getting kicked or stepped on). Other causes of mastitis include coliforms (especially E. coli, Klebsiella spp., Enterobacter aerogenes). They release endotoxins, which enter the bloodstream and can cause endotoxemia and even death. Acute septic mastitis is characterized by fever, anorexia, rumen atony, dehydration, and diarrhea. The affected milk is watery and looks like Gatorade. Treatment involves systemic antibiotics, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, possible fluid therapy, and stripping of all milk every 2 to 4 hours (Fig. 13-18). Mastitis is divided into two major categories based on clinical signs. Clinical mastitis has clinical signs that need no special equipment for detection, for example, palpation of a hard, hot mammary gland or visualization of abnormal milk (clumps of exudates or foul odor). Subclinical mastitis has no obviously visible clinical signs in the udder or in the milk and must be detected by special diagnostic testing. Definitive diagnosis of mastitis is made through sampling and testing milk (Box 13-1). The strip cup is a special milk collection cup with a black lid (Fig. 13-19). The first milk that is expressed from the teat, called the foremilk, should be squirted onto the black lid and observed for abnormalities and odor. Normal milk should be watery, chalky colored, and free of solid clumps; it should not have a sour or fetid odor. Clumps (Fig. 13-20), clots, flakes, abnormal color (Fig. 13-21), blood (Fig. 13-22), and bad odor all are indicators of possible mastitis. Strip cup examination is an important screening test but detects only “clinical mastitis” (obvious clinical signs); it does not detect subclinical mastitis (without visible clinical signs). Further testing is necessary to confirm the disease. Some studies indicate that in any given herd, 90% to 95% of the cows/heifers will test positive for subclinical mastitis. The test uses a white plastic test “paddle” with four cups labeled A to D (Fig. 13-23). The test should not be performed on the foremilk, which typically contains higher SCCs, even in normal milk. The udder is cleaned, and the foremilk is discarded. Then, each quarter is milked into a separate paddle cup. Only enough milk to cover the bottom of the cup is necessary (2–3 ml). One way to ensure the proper volume of milk is to fill all of the cups with several squirts of milk, then briefly tilt the paddle vertically so that excess milk spills from the cup. The test reagent is then added, using an equal volume of reagent as milk in each cup (Fig. 13-24). The paddle is kept horizontal and gently moved in a circular path to produce swirling of the cup contents. The test is read after about 10 seconds of mixing, while continuing to swirl the paddle. Interpretation must be prompt because mild positive reactions tend to disappear after 20 to 30 seconds. Interpretation of the CMT involves two variables: changes in consistency and changes in color. Consistency changes correspond to the SCC and are placed into one of five possible categories (Tables 13-1 and 13-2 and Fig. 13-25). Color changes correspond to the pH of the mixture. The test reagent contains bromcresol purple, a pH indicator that remains purple in alkaline conditions and turns yellow in acidic conditions (pH 5.2). A grade of “+” is given for alkaline milk and “Y” for acidic milk. Acidic milk is unusual. Normal milk has a pH from 6.4 to 6.8. TABLE 13-1 California Mastitis Test: Grading Test Reactions TABLE 13-2 California Mastitis Test: Interpretation of Results Uterine infections are common in cattle after calving because of the high incidence of retained placentas and dystocia. The most common type of uterine infection is endometritis, an infection of the lining of the uterus. It is characterized by a whitish to yellowish mucopurulent vaginal discharge in a cow that has recently given birth (Figs. 13-26 and 13-27). Because the infection is superficial, cows generally show no signs of systemic disease. Occasionally, bacterial infections extend into the deeper layers of the myometrium (metritis), where there is access to blood vessels. Bacteria and bacterial toxins may be absorbed into the bloodstream, resulting in septicemia, endotoxemia, and associated severe systemic illness and shock. Cows with metritis require intensive medical therapy in order to survive. Chronically, bacterial endometritis may develop into pyometra, with accumulation of purulent exudates in the uterus. Clinical signs often include depression, low head carriage, wet cough, open-mouth breathing, weight loss, fever, and wheezing or cracking noises upon auscultation of the lungs (Fig. 13-30). Upon necropsy, the lungs often are dark red and swollen (Fig. 13-31). Abscesses may be present (Fig. 13-32). Diagnosis depends on bacterial culture from necropsied lung tissue. Clinical signs include abscessation of the tongue and possible swelling of the ventral jaw (Figs. 13-33 and 13-34). The bacteria, a normal flora of the upper GI tract, can also cause cutaneous actinobacillosis if other areas of the body are infected (Fig. 13-35).

Common Bovine Diseases

Bacterial Diseases

Anthrax

Blackleg

Calf Enteritis

Foot Rot

Johne Disease

Leptospirosis

Listeriosis

Lumpy Jaw

Mastitis

Mastitis Tests

Strip Cup (Plate) Examination

California Mastitis Test

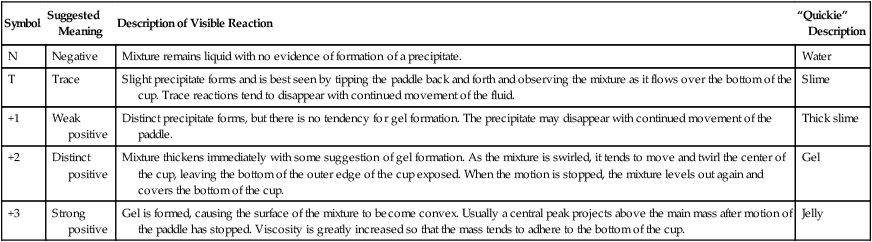

Symbol

Suggested Meaning

Description of Visible Reaction

“Quickie” Description

N

Negative

Mixture remains liquid with no evidence of formation of a precipitate.

Water

T

Trace

Slight precipitate forms and is best seen by tipping the paddle back and forth and observing the mixture as it flows over the bottom of the cup. Trace reactions tend to disappear with continued movement of the fluid.

Slime

+1

Weak positive

Distinct precipitate forms, but there is no tendency for gel formation. The precipitate may disappear with continued movement of the paddle.

Thick slime

+2

Distinct positive

Mixture thickens immediately with some suggestion of gel formation. As the mixture is swirled, it tends to move and twirl the center of the cup, leaving the bottom of the outer edge of the cup exposed. When the motion is stopped, the mixture levels out again and covers the bottom of the cup.

Gel

+3

Strong positive

Gel is formed, causing the surface of the mixture to become convex. Usually a central peak projects above the main mass after motion of the paddle has stopped. Viscosity is greatly increased so that the mass tends to adhere to the bottom of the cup.

Jelly

Test Score

Interpretation in Cattle

N

Normal (0–200,000 cells/ml)

T

Normal (150,000–500,000 cells/ml)

1

Suspicious (500,000–1,500,000 cells/ml)

2

Mastitis (1,500,000–5,000,000 cells/ml)

3

Mastitis (>5,000,000 cells/ml)

Metritis

Shipping Fever

Wooden Tongue

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree