6 Wounds and Injuries

Introduction

Skin injuries can be divided into:

Blunt force injuries

Abrasions

Abrasions are the most superficial of wounds to the skin. When the skin collides tangentially with a rough surface, the outer layers (the keratinised parts) are rubbed off, exposing the more sensitive layers (Fig. 6.1). Remnants of the abraded layers may be found piled up at the edge of the wound.

Bruises (contusions)

Not all bruises are immediately obvious. Hair and skin colour commonly obscure intradermal and subcutaneous bleeding. When it is feasible, clipping/shaving or plucking areas of suspected bruising may be helpful in the live animal (Fig. 6.2), even in very dark-coloured animals such as black Labradors (Fig. 6.3). Clipping/shaving can also be done at the start of the post-mortem examination. In many cases, however, severe bruising may not be discovered until the skin is reflected at post-mortem examination.

The margins of bruises spread and blur with time, making the shape of a bruise an unreliable guide to the outline of the object that struck the body. However, blows by sticks, broom handles or similar narrow objects to relatively hairless skin may leave characteristic ‘tramline bruises’.1 The skin along the line of impact is depressed and compressed by the force of the weapon, whereas the skin at the margins of this area is stretched. This action results in the blood vessels at the centre of the injury being compressed whilst those along the margins are torn. As blood flows back into the area, leakage from the torn vessels results in two linear bruises at the margins of the area of contact by the stick.

Stick marks and other bruising related to transport are common in livestock sent for slaughter.2 They may be recognised in light-skinned pigs before slaughter, but in cattle are more commonly found after skinning. In the subcutis and superficial muscles, the bruises do not usually develop a ‘tramline’ appearance.

Extensive bruising of livestock, found at slaughter, can be the first direct evidence that a significant husbandry problem exists on a farm (Fig. 6.4) or that there are major deficiencies in the transport arrangements. The veterinarian’s report will be a key element in the subsequent investigation.

Age of bruising

As the bruise ages, red cells rupture and haemoglobin degrades. This causes the sequence of colour changes readily seen in animals and birds with light-coloured skin that survive the injury by several days. Observations of poultry3 record bruises changing from red at 2 minutes post-trauma through dark red–purple at 12 hours, light green–purple at 24 hours, yellow–green–purple by 36 hours, becoming yellow–green at 48 hours and yellow–orange at 72 hours, reducing to be ‘slightly yellow’ at 96 hours and normal by 120 hours post-injury.

Because of economic losses related to trimming of bruised meat from slaughtered animals, there has been considerable interest in establishing when these bruises occurred. The approximate age of bruises in cattle and sheep, as judged by their macroscopic appearance, ranges from red and haemorrhagic between 0 and 10 hours after injury, dark coloured when approximately 24 hours old, watery in consistency by 24–38 hours, and having a rusty orange colour and a soapy texture when more than 3 days.4

Research conducted in Australia on lambs and calves5 has provided a guide to histological ageing of bruising over the 0–48-hour period after trauma in these animals. This research showed that trauma occurring immediately before death can lead to haemorrhage in subcutaneous tissues, in the muscle septa, and between muscle fibres. Small numbers of neutrophils and macrophages are present in the extravasated blood. At 8 hours after trauma, the extent of the bleeding is greater and fibrin strands are recognisable. Many neutrophils and few macrophages are present in the extravasated blood, the damaged muscle and the subcutis. The amount of haemorrhage changes little between 8 and 24 hours after injury, but the ratio of neutrophils and macrophages alters so that they are found in approximately similar numbers at 24 hours. This change in cell population continues over the subsequent 24-hour period, resulting in macrophages greatly outnumbering neutrophils by 48 hours after trauma. At this time, capillaries with plump endothelium can also be seen invading the damaged tissues.

Testing for the formation of bilirubin (as haemoglobin is broken down in the area of the bruise) has also been used to estimate the time elapsed since injury. This method is based on the colour change seen in samples of bruised muscle after being soaked in a mixture of trichloroacetic acid and ferric chloride.4

Lacerations

Lacerations are caused by blunt trauma that results in tearing or splitting of the tissues. They can be accidental, as in motor vehicle accidents (Fig. 6.5), or can be caused by heavy blows from a blunt weapon, or by violent shaking and tearing, during which the skin and deeper tissues are stretched until they tear.

Fig. 6.5 Dog. Laceration of the skin over the back and on to the flank of a dog killed in a road accident.

Lacerations frequently do not conform to the shape of the object that inflicted the damage, and severely lacerated muscle may be present underneath intact skin (e.g. see Bite wounds).

Head, face and neck injuries

Head injuries

The head is a common target for blows to dogs and cats. A hammer, stick or spade may be used to club dogs and foxes, whilst hammer blows can also cause fatal head injuries to calves. Whenever possible, the suspect weapon should be examined in order to gauge whether, because of its shape, size and weight, it could have caused the injuries. Equally importantly, it may be found that the flimsiness of the putative weapon raises doubts that it was used to fracture a mature skull. The weapon should be examined for blood traces and adherent hairs (Fig. 6.6).

Depending on the type of object striking the head, superficial soft tissue injury might consist of abrasions, lacerations or incised wounds. Subcutaneous bruising usually accompanies blunt trauma to the head and can be valuable in establishing the nature and direction of the blow(s) (Case study 6.1, Fig. 6.7). Extensive or marked intramuscular haemorrhage in the temporalis muscles of dogs suggests high-energy trauma.

Case study 6.1

The only external sign of injury was a small bruise on the left side of the head, at the base of the ear. Internally, severe bruising was present over the right dorsal and lateral aspect of the head but the skull was not fractured in this area (Fig. 6.7). On the left side of the face and head, bruising overlay part of the upper jaw and cheekbone, and extended into the adjacent muscles. The cheekbone was fractured in two places and a depressed fracture involved much of the side of the skull. A large haemorrhage was present within the left side of the brain.

Absence of bruising over the head in cases where there is a history (or witness evidence) of the animal having been beaten on the head, suggests that either the history is wrong (Case study 6.2) or the beating occurred after death.

Case study 6.2

2 Was there evidence of diarrhoea to account for the history of inappropriate elimination in the house?

Skull fractures and specific injuries

Radiological interpretation

The radiological classification used for skull fractures in abused children6 is equally appropriate for abused pets and livestock. Skull fractures are divided into simple or complex categories. Simple fractures are single lines that extend in a straight, jagged or curved manner. These fractures do not cross sutures. In complex fractures there is more than one fracture line. Further useful descriptors are comminuted, depressed and elevated.

Parietal crest

Because of the prominence and strength of the parietal crest in adult badgers, dogs and pigs, fracture of this crest suggests a direct heavy blow to the top of the head (Case study 6.3, Fig. 6.8).

Case study 6.3

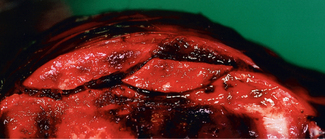

An adult female badger was found dead in a small stream.

Three small superficial wounds were present on the head. Reflection of the skin from the head revealed massive haemorrhage over the top of the head and extending down across the forehead. Linear laceration of the muscles was present midline on the head parallel to the parietal crest. This crest was fractured with two large portions being displaced (Fig. 6.8). No other skull fractures were detected. Intramuscular haemorrhage was found to extend down the right side of the head. Haemorrhage was present on the undersurface of the brainstem and in the sulci of the cerebrum.

The cause of death was drowning.

Depressed fractures

Complex depressed fracture of the skull often can be readily identified on X-ray. However, the extent of the damage is sometimes easier to appreciate at post-mortem examination (Case study 6.4, Figs 6.9 & 6.10).

Case study 6.4

A terrier-type bitch, aged between 5 and 7 months, was reportedly struck on the head by the owner’s husband with the handle of his walking stick. X-ray plates showed complex fracturing of the top of the skull and, in view of the severity of the injuries (Fig. 6.9), the dog was euthanased.

Post-mortem examination revealed the full extent and distribution of the cranial fractures (Fig. 6.10). Additionally, bruising was present over the ribs, although no rib fractures were found and no significant injury affected the heart or lungs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree