Screening for problems involves only Steps 1 and 2 of welfare assessment. Screening does not involve an overall evaluation but highlights issues for further investigation. It is useful during routine consultations such as vaccinations or geriatric health-checks, and it can encourage owners to consider issues such as diet, parasite control, osteoarthritis and exercise. Screening can also be used to monitor for disease alterations and treatment side effects.

In comparison, gauging welfare involves all three steps of assessment. Gauging welfare does involve an evaluation, so it assesses which treatment options will provide the best welfare for the patient. It can encourage owners to make decisions and provide consent. Gauging can also be used to monitor disease progressions, improvements or deteriorations and treatment effects.

The different steps in assessment provide scope for possible errors and disagreements between different people. Evidence of such differences in veterinary contexts is relatively unstudied, but one veterinary research paper incidentally reported some differences between proxies in assessing demeanour (Graham et al. 2002) and similar disagreements appear common in human medicine. Many veterinary professionals can recall examples where their assessments have disagreed with those of owners, paraprofessionals or colleagues. Disagreement may occur during any step of the assessment process.

In Step 1, people may have different information. For example, an owner may have seen what the animal is like at home but not in surgery. They may be unaware of diagnostic facts or have failed to notice a behaviour or symptom. Differences in memory can mean that people forget information, or that they forget what an animal’s welfare was like previously, especially if there has been a gradual decline or improvement. People may also have incorrect information through unfounded assumptions or misinformation.

In Step 2, people may interpret the available information differently, due to different levels of empathy or abilities to understand scientific knowledge. They may have different ideas about what information is important, e.g. whether pathophysiological or behavioural indicators are more important. They may have different background knowledge or experience. They may also have different knowledge of the individual patient.

In Step 3, people may use different methods of evaluation. People have varying opinions on how worthwhile feelings are (e.g. whether pain is more important than fear). They may be biased by personal interest; for example, a desire to justify continued treatment may predispose them to rating welfare as disproportionately high. People may impose their own values (e.g. needle-phobia), have different personal experiences or undergo a response shift.

Welfare scientists have spent a lot of time designing and validating assessment methods to reduce these disagreements. Inter-observer and intra-observer reliability are suggested as key attributes of a good welfare assessment method. Such consistency is useful to make farm assurance schemes more fair, to evaluate welfare variations when assessors change (e.g. between nursing shifts) and in experiments and clinical trials that need to be repeatable. Reliability is actually less important in veterinary practice: what is important is accuracy (and if an assessment is wrong, reliability simply means that it is consistently wrong).

The possibilities of disagreements and errors raise the question of who is best placed to assess welfare. Veterinary surgeons will generally have more experience of welfare assessment than owners. Veterinary nurses and owners may spend more time with an individual animal and have more knowledge of the animal’s inputs, behaviours and individual personality. Different assessors may therefore be better placed in different cases. More importantly, collaboration can combine all the valuable information, interpretations and evaluations from every contributor.

Veterinary professionals can contribute a lot to such joint assessments. For Step 1, we can provide clinical knowledge and diagnostic skills. For Step 2, veterinary professionals have experience of interpreting information about diseases and clinical symptoms into animal’s feelings and using scientific methods and critical anthropomorphism. For Step 3, veterinary professionals can help to guide the partnership through an appropriate evaluation process. In all steps, veterinary professionals can also help to correct errors that owners may make and provide encouragement and support. The rest of this chapter goes through the steps of welfare assessment, suggesting ways in which veterinary professionals can make accurate and reliable welfare assessments.

INFORMATION

3.2 Histories

The first step in animal welfare assessment is to work out what information to obtain. There is no point in trying to get information that is irrelevant, unavailable or meaningless – in busy veterinary practice, we only just have enough time to assess the things that are worth assessing. Determining what to assess involves four (or five) questions, listed in Box 3.1.

Question (1) has been answered in Chapter 1. What is important to an animal is the valence and intensity, duration and frequency of its feelings, and the achievement or avoidance of anything that causes or signifies such feelings. Question (2) means we must focus not on trying to directly see animals’ feelings, but on available information about inputs and indicators. We cannot see a cow’s pain, but we can detect a sole ulcer, which may cause it, or non-weight-bearing, which may indicate it. Question (3) reminds us to focus on information that helps us make practical decisions for the animal’s benefit. We may require different information depending on whether we want to screen for problems or to gauge welfare, on how we plan to interpret and evaluate the information and on what decision we have to make. Question (4) reminds us that diagnostics may be harmful if they require repeated visits, restraint or anaesthesia, and these risks need to be balanced against the benefits of the information (Question (5) will be discussed in later sections).

Before the consultation, clinical records can provide information about an animal’s or herd’s previous problems, geographical location, vaccination history, previous vet-fear or in-practice aggression, signalment (e.g. its age, gender, and breed) and the owner’s other animals. Further valuable information is usually provided by the owner’s opening statement, which can reveal the owner’s animal welfare assessment, priorities and personal motivation. Owners may not present all welfare issues, especially problems they do not feel are veterinary issues, such as fear-related or separation-related issues.

Veterinary professionals therefore need to actively gather more information about the animal’s inputs (Box 3.2) and indicators (Box 3.3), especially the animal’s current levels and recent changes. These should be related to the individual patient’s preferences, fears and likes. Relevant information includes facts about the owner, such as their beliefs about animal welfare and how they assess it, their level of care and knowledge, their planned inputs and what recommendations they are likely to comply with and what they want and expect. Some information can be obtained by explicit, if tactful, questions. Other information needs to be indirectly inferred, by mindreading through similar critical reasoning to how we infer animals’ feelings.

- Disease

- Congenital

- Acquired

- Old age

- Congenital

- Disability

- Injury

- Abuse

- Inter-animal aggression

- Nutrition

- Poisons

- Insufficient water

- Insufficient food

- Inappropriate food

- Excessive food

- Enjoyable food

- Unpleasant food (e.g. eating unpalatable medicines or while nauseous)

- Force-feeding

- Poisons

- Environment

- Risks of injury

- Insufficient bedding or thermal extremes

- Lack of space

- Being unable to predict their environment

- Interruption of normal routine

- Threatening stimuli

- Novelty

- Inability to control their environment

- Kennelling

- Risks of injury

- Conspecific company

- Positive interactions

- Isolation

- Aggression

- Loss of resources

- Positive interactions

- Human company

- Rewards/enjoyable interaction

- Company of usual carer

- Abuse

- Punishment

- Humans associated with previous negative or positive interactions

- Rewards/enjoyable interaction

- Company of other animals

- Predation

- Loss of resources

- Predation

- Treatment

- Transport

- Visiting the practice

- Restraint

- Punishment

- Hospitalisation

- Anaesthesia

- Surgery

- Medications

- Transport

- Vomiting, diarrhoea and imbalance

- Grooming, licking and scratching

- Repetitive behaviours

- Eating and drinking

- Weight changes

- Sleeping

- Activity and willingness to exercise/go out

- Engagement with toys and play

- Interaction with other animals, including allogrooming

- Responses to humans, including willingness to interact and specific responses to human approach

- Altered posture

- Paw-lifting and pawing

- Frequency and types of vocalisations

- Escape behaviours

- Shaking or trembling

- Hiding

- Gait, soundness and ease of movement

- Guarding a particular area, and prayer-posture

- Grooming, licking and scratching at a particular area

- Overall demeanour

- Any other abnormal behaviours

- Any other unnatural behaviours

- Any other behaviours

- Freedom from thirst, hunger and malnutrition – by ready access to fresh water and a diet to maintain full health and vigour

- Freedom from discomfort – by providing an appropriate environment including shelter and a comfortable resting area

- Freedom from pain, injury and disease – by prevention or rapid diagnosis and treatment

- Freedom to express normal behaviour – by providing sufficient space, proper facilities and company of the animal’s own kind

- Freedom from fear and distress – by ensuring conditions and treatment which avoid mental suffering

- Opportunity for selection of dietary inputs – by provision of a diet that is preferentially selected

- Opportunity for control of environment – by allowing the achievement of motivations

- Opportunity for pleasure, development and vitality – by maintaining and improving beneficial inputs

- Opportunity to express normal behaviour – by providing sufficient space, a proper range of facilities and the company of the animal’s own kind

- Opportunity for interest and confidence – by providing conditions and treatment which lead to mental enjoyment

There are many potential barriers to obtaining information through owners. Owners may fail to provide information about certain issues through not observing, recognising or remembering them. Owners may also misreport issues through poor memory, misinterpretation or dishonesty. Some owners may deliberately hide information, for example if they think revealing it could lead to legal prosecution, moral criticism or a euthanasia decision. Other barriers are due to our limitations. We may interrupt, misinterpret and fail to ask, listen, follow-up or remember. We may lack enough time to collect sufficient information, especially when owners are particularly recalcitrant or loquacious. We may make erroneous prejudgements or assumptions about situations and owners.

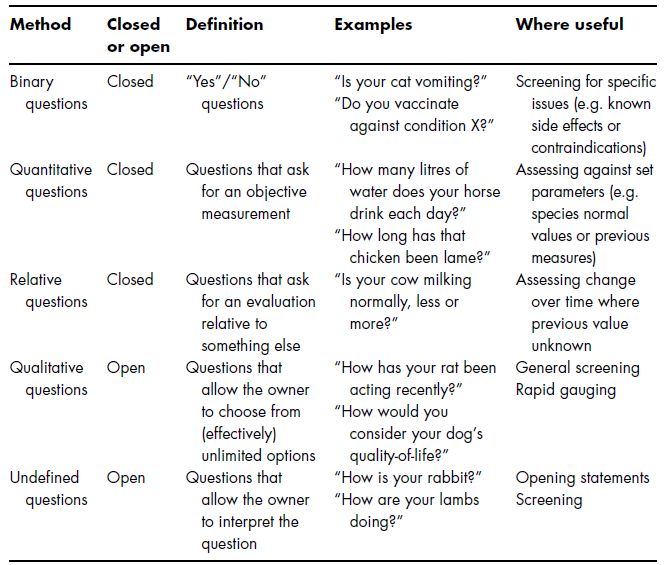

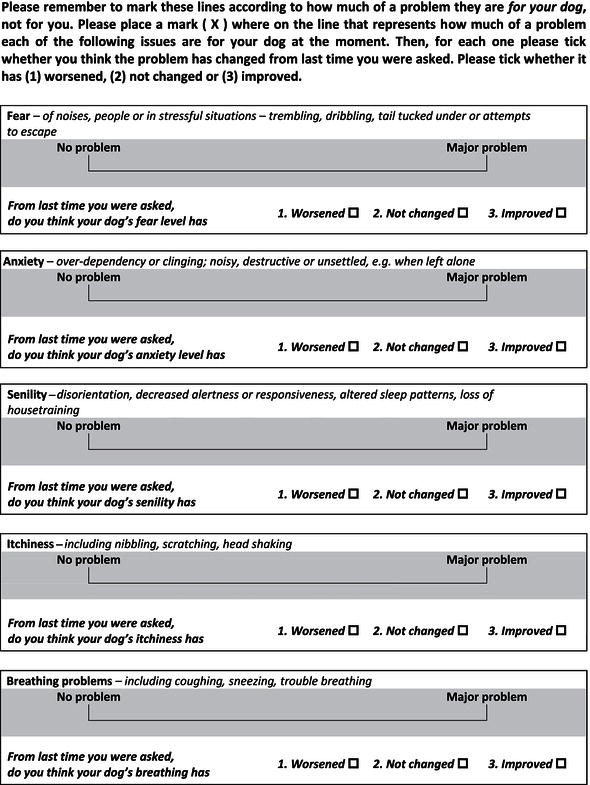

Veterinary professionals can gain more information efficiently by using pre-organised frameworks. One can structure discussions around frameworks such as the five welfare needs (Box 1.2) or focus on feelings and causes, such as the five freedoms (Box 3.4), perhaps supplemented with five opportunities to consider positive welfare as well (Box 3.5). Different questioning techniques can be useful in different cases (Table 3.1). Alternatively, owners can be asked to complete a paper-based questionnaire before the consultation. An example for dogs is given in Figure 3.2 that looks at specific responses and welfare needs.

Table 3.1 Methods of questioning.

3.3 Clinical Examinations

One can also gain information from examination (Figure 3.3). It is useful to first look at the animal’s overall demeanour, and then at more general symptoms of arousal and valance.

Closer clinical examination can provide evidence of causes of welfare problems. Disease can be assessed by feeling or listening for abnormalities (e.g. a mass or an irregular heart-beat). Injuries can be inspected visually or palpated. Nutrition can be assessed using bodyweight and body condition score. Hydration can be assessed by checking mucous membranes (Pritchard et al. 2005) and skin turgor. Examination can also provide an idea of whether the condition is acute or chronic.

Figure 3.2 Assessing owners’ perceptions of dog responses and needs. (Adapted from Mullan and Main 2007.)

Figure 3.3 Veterinary professionals can obtain information on causes and symptoms from clinical examination. (Courtesy of RSPCA Bristol.)

Clinical examination includes observation of animals’ physiological symptoms, both general and local. Clinicians can assess an animal’s immune system (e.g. inflammation, lymph gland enlargement, discharges and pyrexia), endocrine system (e.g. heart rate and dermatology), renin-angiotensin system (e.g. hydration and skin turgor), cardiovascular system (e.g. heart rate and mucous membranes) and nervous system (e.g. lameness, guarding or licking at an area and vocalisations), as well as specific symptoms such as chromodacryorrhoea (the red tears that can be an indicator of stress in rats) and local symptoms such as erythema (redness) and swelling. Measures of sympathetic activation can indicate arousal, using inexpensive methods such as temperature, pupil dilation, heart rate and respiratory rate (plus each can be altered by pathological processes). As suggested in Chapter 1, many animals are iatrogenically aroused by being at the veterinary practice, so these measurements may simply indicate vet-fear and should be interpreted accordingly.

Clinical examination also includes observing behavioural symptoms, both spontaneous and induced. Clinicians can assess locomotive activity, limb withdrawal, vigilance behaviours and responses to objects or people. For example in horses, locomotive activity may be an indicator of stress (Houpt & Houpt 1989), responses to human approach or contact with areas such as head or chin may indicate fear (Pritchard et al. 2005) and pawing or snorting may indicate stress (Visser et al. 2008).

Clinicians can use formalised methods to quantify particular issues. Emaciation can be assessed using bodyweight, girth or standardised body condition scores. Pain is one phenomenon for which no simple, objective measure has been identified (Rutherford 2002), but one can nonetheless assign scores (Hawkins 2002). There are also frameworks for assessing pruritus, disease severity, fractures and many clinical issues, as well as overall welfare, quality-of-life or health-related-quality-of-life scoring systems (see further reading). Clinical examination often compares findings to what is normal for the individual, breed or species, usually based on the practitioner’s experience.

One advantage of using clinical measures is that they seem to be more objective and more scientific than qualitative judgements. However, there can still be differences between assessors. For example, Burn et al. (2009) reported that assessments of body condition were sufficiently reliable for clinical use, but that assessment of hoof quality, hock injuries, mucous membrane abnormalities and skin tenting were not. One disadvantage of using clinical findings is that they may lead to an excessive focus on pathophysiological issues. This may be especially likely for veterinary professionals, who have scientific and medical backgrounds (McMillan & Rollin 2001). This problem is also recorded in the medical profession (Bradley 2001), where doctors can thereby miss opportunities to achieve other welfare improvements.

Another disadvantage of clinical examinations is that they require handling and restraint, which can cause stress, especially when the test is particularly strange (e.g. tonometry to measure intraocular pressure), when the animal is in an unusual environment (e.g. a darkened consulting room), or when the veterinary staff are stressed themselves (e.g. by time constraints or an uncooperative patient). Some tests are unpleasant in certain situations, such as testing an animal’s pupillary light reflex (how their pupils react to changes in light intensity) if the animal is photophobic, or pain withdrawal assessment. In some cases, remote examination from a distance or from outside the cage can gain information before or instead of physical restraint. In other cases, sedation or anaesthesia may be less harmful than conscious handling. In some cases, it may be better not to perform a full examination or to delay some handling until after administering analgesia or anaesthesia.

3.4 Further Investigations

Clinicians can also obtain information from further tests such as laboratory tests, imaging, electrographics (e.g. electrocardiograms to assess heart function) and specialist physical examination tests. Further tests usually look for deviations from physiological normality. In some cases, there are lists of normal parameters for various populations. In other cases, one can use comparisons to the individual’s normal state, for example by referring to previous radiographs of the same area or contralateral radiographs of the animal’s healthy side.

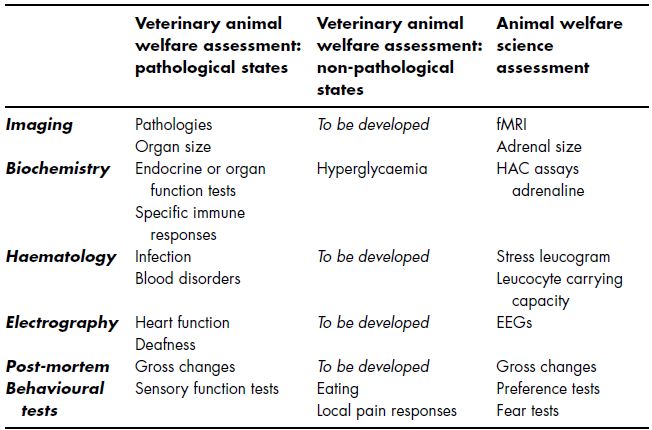

Table 3.2 Example uses of further tests as welfare measures in and outside veterinary practice.

As Table 3.2 suggests, there are lots of measures that veterinary surgeons use to identify specific welfare harms due to pathologies and lots of animal welfare measures that are used in fields outside veterinary practice. Contrastingly, there are few non-pathological measures used in veterinary practice for welfare assessment.

Biochemical and haematological measures can be assessed by analysing animals’ blood samples and can provide information about the welfare of animals as diverse as horses (Hamlin et al. 2002; Robson et al. 2003) and ball pythons (Kreger & Mench 1993). Veterinary professionals often measure biochemical and haematological values as routine screening or as tests for conditions such as inflammation, dehydration and acidosis (where the animal’s blood pH is too acidic).

Veterinary practitioners usually assess hypothalamo-adreno-cortical (HAC) axis responses to evaluate endocrine functioning. Animal welfare scientists use the same hormonal measures to assess non-specific stress responses in both the short term (e.g. increased cortisol, corticosterone and their metabolites) and long term (e.g. altered ACTH-stimulation or dexamethasone-suppression tests), measured in the saliva, plasma, serum, urine or faeces. Plasma cortisol assays can be done through most practices’ commercial laboratories, but are relatively expensive, especially considering that most animals in a practice or during an intervention are likely to be stressed, making an elevated cortisol level of limited usefulness.

In comparison, clinicians (and animal welfare scientists) do assess moderate hyperglycaemia (high blood sugar) and glycosuria (sugar in the urine) as a measure of stress in cats. However, we often fail to consider the welfare implications; indeed, we often deliberately ignore stress-induced hyperglycaemia, because we are focusing on assessing endocrine function and describe it as spurious. But such hyperglycaemia actually provides a useful indication that a cat is stressed, which should confirm the importance of considering the manner and frequency of rechecks and further tests (and the lack of hyperglycaemia may make us feel more tests may be less iatrogenically harmful). It may be true that feline hyperglycaemia is common in veterinary practices, but this highlights how many cats routinely experience vet-fear.

Figure 3.4 Biological measures such as bodyweight can be objectively measured over time.

(Courtesy of RSPCA Bristol.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree