10 Vomiting

Pathophysiology of vomiting

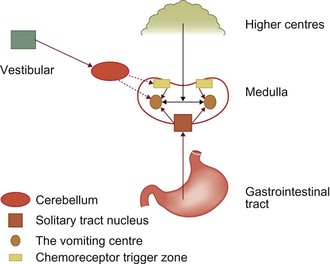

Vomiting is a reflex act resulting from stimulation of the vomiting centre in the brain stem (Fig 10.1). The vomiting centre receives afferent input from peripheral receptors in the viscera from the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CRTZ) in the floor of the fourth ventricle of the brain, from the vestibular apparatus and from the higher centres of the brain such as the cerebral cortex. The peripheral visceral receptors are located throughout organs in the body, especially in the duodenum, sometimes referred to as ‘the organ of vomition or nausea’. Distension or irritation of the intestinal mucosa may stimulate the vomiting centre and inflammation of other organs such as the pancreas can also result in vomiting. Afferent nerve fibres run from these organs in the vagal and sympathetic nerves.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree