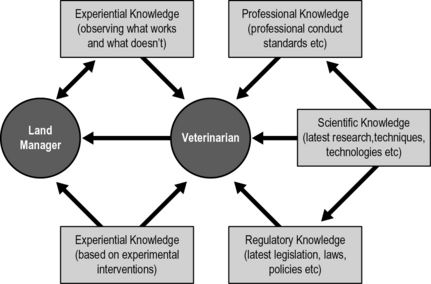

9 After reading this chapter, students will be able to: • Understand the key ways in which veterinarians maintain and renew their knowledge once in practice. • Appreciate the contribution of experiential and experimental knowledge derived from on-the-job learning to veterinary expertise. • Understand how interaction with veterinary colleagues, clients and other professionals contributes to the development of veterinary knowledge and expertise • Realize that veterinarians have a key role to play as knowledge brokers within the agri-food system. • Recognize the importance of veterinarians understanding the value of their knowledge and their potential brokerage role as a marketable product within the veterinary business. The Foresight Report on the future of food and farming in the UK identified the improvement of advisory services to farmers, land managers and food producers as a top priority in tackling the challenges of food security (Foresight, 2010, 2011). Changing commercial and legislative pressures on farmers create a need for up-to-date professional advice. However, concerns have been raised over the capacity of the agricultural advisory system to incorporate the latest insights from science (Oreszczyn et al., 2010; Van Crowder and Anderson, 1997). In animal husbandry, the requirement to increase productivity, while at the same time protecting the environment and animal welfare, necessitates continuous improvements in the skills and knowledge applied to livestock management under veterinary advice and direction. Furthermore, as government hands over more of the responsibility for managing animal health and disease risk to the agricultural industry, vets have to rethink the services they provide to their customers. Veterinary work can be conceptualized as a suite of services for livestock and food producers, including knowledge transfer, evaluation and planning. Knowledge management and getting expert advice to where it is needed are absolutely critical to the effectiveness of risk management and responsibility sharing. The new external challenges facing farming and food production (e.g. climate change, potential shifts in disease patterns, economic and energy concerns, and an emerging policy focus on food supply and risk) place a premium on knowledge that is up to date, authoritative, practical and targeted. Veterinary graduates qualify with an impressive knowledge and skill set, but there are questions concerning the extent to which professional and lifelong learning skills are integrated into the curriculum (May, 2008). In this chapter we explore how veterinarians maintain their knowledge, skills and expertise once their formal training has concluded and they enter professional practice. When asked what formal knowledge updates they need to draw on in their work, vets refer not just to scientific knowledge but also to professional knowledge, such as that concerning professional standards and conduct, and regulatory knowledge, concerning policy or guidance documents, and new legislation impacting the profession (as illustrated in the right-hand side of Figure 9.1). The formal professional, regulatory and scientific sources veterinarians draw upon do not, however, fully reflect the range of ways they keep their expertise up to date and problem-solve. Advisors actively broker a range of different types of knowledge, besides formal science, including generating knowledge themselves through learning on the job. For veterinarians, great significance is placed on this field-generated knowledge (see the left-hand side of Figure 9.1). Therefore, we need to rethink traditional understandings of their role as simply intermediaries of formal knowledge. As agents of knowledge exchange, veterinarians relay information and expertise to farmers, much of which is drawn from professional, regulatory and scientific sources. However, veterinarians are not simply transferors to their clients of formal knowledge from scientists or other experts; they are also agents of knowledge application, adaptation and practical problem solvers. As a result, they are able to produce interactively distinctive and specialized field knowledge.Veterinarians’ field knowledge comprises both experiential and experimental knowledge. Experiential and experimental knowledge are derived from observation and intervention in practice; they are related in that they both stem from ‘direct experience’ (Fazey et al., 2006). These forms of knowledge become implicit through an ‘intuitive process, based on substantial, long-term and reflected experience’ (Baars, 2011, p. 602).

Veterinary field expertise and knowledge exchange

LEARNING OUTCOMES

The knowledge systems of field veterinarians

The significance of field-generated knowledge

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine